The Autonomous Chieftains: Genesis and Growth (1540-1545 A. D.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Historical Thar Desert of India

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 12 No 4 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) www.richtmann.org July 2021 . Research Article © 2021 Manisha Choudhary. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Received: 14 May 2021 / Accepted: 28 June 2021 / Published: 8 July 2021 The Historical Thar Desert of India Manisha Choudhary Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Delhi, India DOI: https://doi.org/10.36941/mjss-2021-0029 Abstract Desert was a ‘no-go area’ and the interactions with it were only to curb and contain the rebelling forces. This article is an attempt to understand the contours and history of Thar Desert of Rajasthan and to explore the features that have kept the various desert states (Jodhpur, Jaisalmer, Barmer, Bikaner etc.) and their populace sustaining in this region throughout the ages, even when this region had scarce water resources and intense desert with huge and extensive dunes. Through political control the dynasts kept the social organisation intact which ensured regular incomes for their respective dynasties. Through the participation of various social actors this dry and hot desert evolved as a massive trade emporium. The intense trade activities of Thar Desert kept the imperial centres intact in this agriculturally devoid zone. In the harsh environmental conditions, limited means, resources and the objects, the settlers of this desert were able to create a huge economy that sustained effectively. The economy build by them not only allowed the foundation and formation of the states, it also ensured their continuation and expansion over the centuries. -

The Cultural Heritage of North India

Mughals, Rajputs & Villages: The Cultural Heritage of North India 4 FEB – 25 FEB 2020 Code: 22001 Tour Leaders Em. Prof. Bernard Hoffert Physical Ratings Prof. Bernard Hoffert leads this tour visiting three magnificent capitals of the Mughal Empire – Delhi, Agra & Fatehpur Sikri – and a number of great Rajput fortress cities of Rajasthan. Overview Tour Highlights Professor Bernard Hoffert, former World President of the International Association of Art-UNESCO (1992-95), leads this cultural tour of North India. Visit three magnificent princely capitals in the heartland of the Mughal Empire – Delhi, Agra and Fatehpur Sikri – and a number of great Rajput fortress cities of Rajasthan. Explore the fusion of Indian and Islamic cultures at Mughal monuments, such as Agra's Red Fort, Shah Jahan's exquisite Taj Mahal, and Akbar the Great's crowning architectural legacy, Fatehpur Sikri – all of which are UNESCO World Heritage sites. The opulence and grandeur of Mughal architecture is also experienced at a number of matchless Rajput palaces. Stay in former palaces that are now heritage hotels – an experience which enhances our appreciation of this sumptuous world. Visit great Hindu and Jain temples, encounter the vernacular architecture of Rajasthan, including its famous stepped wells and villages, and explore fortresses like Jaisalmer and Bikaner that rise from the Thar Desert in the state's north. Explore the vibrant folk culture of Rajasthan, manifest in its fine music, dance and textiles. Experience a boat cruise on Lake Pichola at Udaipur, a 4WD drive excursion to view blackbuck (an endangered species of antelope native to the Indian subcontinent) and an elephant ride in Jaipur. -

57C42f93a2aaa-1295988-Sample.Pdf

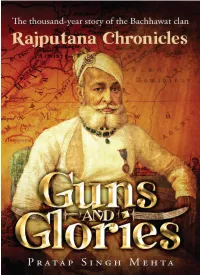

Notion Press Old No. 38, New No. 6 McNichols Road, Chetpet Chennai - 600 031 First Published by Notion Press 2016 Copyright © Pratap Singh Mehta 2016 All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-93-5206-600-1 This book has been published in good faith that the work of the author is original. All efforts have been taken to make the material error-free. However, the author and the publisher disclaim the responsibility. No part of this book may be used, reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. The information regarding genealogy of Deora Chauhans and Bachhawat Mehtas, available from different books of history, internet, “Bhaats” (story tellers) and inscriptions, is full of contradictions and the names are at variance. The history of any person or place is also the perception and objective of the writer. However, care has been taken to present the paper factually and truly after due moderation. Therefore, the author and publisher of this book are not responsible for any objections or contradictions raised. Cover Credits: Painting of Mehta Rai Pannalal: Raja Ravi Varma (Travancore), 1901 Custodian of Painting: Ashok Mehta (New Delhi) Photo credit: Ravi Dhingra (New Delhi) Contents Foreword xi Preface xiii Acknowledgements xvii Introduction xix 1.1 Genealogy of Songara and Deora Chauhans in Mewar 4 1.2 History – Temple Town of Delwara (Mewar) 7 Chapter 1.3 Rulers of Delwara 10 12th–15th 1.4 Raja Bohitya Inspired by Jain Philosophy 11 Century -

Bikaner Travel Guide - Page 1

Bikaner Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/bikaner page 1 Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, umbrella. When To Max: Min: 28.5°C Rain: Bikaner 32.79999923 91.0999984741211 706055°C mm A majestic city of forts and royal Aug palaces, Bikaner is a famous VISIT Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, destination in Rajasthan well umbrella. http://www.ixigo.com/weather-in-bikaner-lp-1159358 Max: Min: Rain: known for its vibrancy and rich 31.70000076 27.39999961 82.5999984741211 culture all across the globe. There 2939453°C 8530273°C mm Jan are several great places to visit in Famous For : City Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Sep Bikaner like Junagarh Fort, The Max: Min: Rain: Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. Bikaner, 14.30000019 8.100000381 5.69999980926513 Max: Min: Rain: National Research Centre on 0734863°C 469727°C 7mm 30.70000076 25.89999961 40.7999992370605 Camel, Karni Mata Temple, Gajner a royal city in Rajasthan has almost every 2939453°C 8530273°C 5mm Feb thing to attract tourists. The sweets and Palace, Lallgarh Palace, Jain Temple Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Oct snacks of the city are well known for its Bhandasar and Kodamdesar Max: Min: Rain: Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. delicious taste. The city was founded by an 17.20000076 11.89999961 7.80000019073486 Max: Min: Rain: Temple. 2939453°C 8530273°C 3mm 27.70000076 20.79999923 10.1000003814697 audacious Rathore prince Rao Bikaji in 1486. 2939453°C 7060547°C 27mm Retaining the glory of the olden times all Mar Nov across the amplitude, Bikaner portrays a Cold weather. -

Birds & Culture on the Maharajas' Express

INDIA: BIRDS & CULTURE ON THE MAHARAJAS’ EXPRESS FEBRUARY 10–26, 2021 KANHA NATIONAL PARK PRE-TRIP FEBRUARY 5–11, 2021 KAZIRANGA NATIONAL PARK EXTENSION FEBRUARY 26–MARCH 3, 2021 ©2020 Taj Mahal © Shutterstock Birds & Culture on the Maharajas’ Express, Page 2 There is something indefinable about India which makes westerners who have been there yearn to return. Perhaps it is the vastness of the country and its timeless quality. Perhaps it is the strange mixture of a multiplicity of peoples and cultures which strikes a hidden chord in us, for whom this land seems so alien and yet so fascinating. Or perhaps it is the way that humans and nature are so closely linked, co-existing in a way that seems highly improbable. There are some places in a lifetime that simply must be visited, and India is one of them. Through the years we have developed an expertise on India train journeys. It all started in 2001 when VENT inaugurated its fabulous Palace on Wheels tour. Subsequent train trips in different parts of the country were equally successful. In 2019, VENT debuted a fabulous new India train tour aboard the beautiful Maharajas’ Express. Based on the great success of this trip we will operate this special departure again in 2021! Across a broad swath of west-central India, we will travel in comfort while visiting the great princely cities of Rajasthan state: Udaipur, Jodhpur, and Jaipur; a host of wonderful national parks and preserves; and cultural wonders. Traveling in such style, in a way rarely experienced by modern-day travelers, will take us back in time and into the heart of Rajput country. -

Inclusive Revitalisation of Historic Towns and Cities

GOVERNMENT OF RAJASTHAN Public Disclosure Authorized INCLUSIVE REVITALISATION OF HISTORIC TOWNS AND CITIES Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK FOR RAJASTHAN STATE HERITAGE PROGRAMME 2018 National Institute of Urban Affairs Public Disclosure Authorized All the recorded data and photographs remains the property of NIUA & The World Bank and cannot be used or replicated without prior written approval. Year of Publishing: 2018 Publisher NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF URBAN AFFAIRS, NEW DELHI Disclaimer While every effort has been made to ensure the correctness of data/ information used in this report, neither the authors nor NIUA accept any legal liability for the accuracy or inferences drawn from the material contained therein or for any consequences arising from the use of this material. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form (electronic or mechanical) without prior permission from NIUA and The World Bank. Depiction of boundaries shown in the maps are not authoritative. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on these maps do not imply official endorsement or acceptance. These maps are prepared for visual and cartographic representation of tabular data. Contact National Institute of Urban Affairs 1st and 2nd floor Core 4B, India Habitat Centre, Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110003 India Website: www.niua.org INCLUSIVE REVITALISATION OF HISTORIC TOWNS AND CITIES STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK FOR RAJASTHAN STATE HERITAGE PROGRAMME 2018 GOVERNMENT OF RAJASTHAN National Institute of Urban Affairs Message I am happy to learn that Department of Local Self Government, Government of Rajasthan has initiated "Rajasthan State Heritage Programme" with technical assistance from the World Bank, Cities Alliance and National Institute of Urban Affairs. -

Animal Genetic Resources Information Bulletin

47 THE CAMEL BREEDS OF INDIA IN SOCIAL AND HISTORICALPERSPECTIVE Ilse Kohler-Rollefson Pragelatostraße 20, D - 6105 Ober-Ramstadt, GERMANY SUMMARY This artiele traces the evolution of one-humped camel {C. dromedarius) breeds in India and describes the social and historical factors that contributed to their formation. In India a number of distinct breeds developed from the breeding herds maintained by the Maharajahs of Rajputana for supplying camels for desert warfare. After a summary of the literature, details are provided on the characteristics and historical background of the individual breeds or types. The threats to the continued existence of these breeds and their genetic diversity are also evaluated. RESUME Cet article met en evidence 1’evolution des races de dromadaires (C. dromedarius) aux Indes et decrit les facteurs sociaux et historiques qui ont contribue a leur formation. Aux Indes, un nombre de races differentes s’est developpe a partir de troupeaux d’elevage maintenus par les Maharajas de Rajputana pour avoir a disposition des chameaux pour les guerres dans le desert. Apres un aperçu sur la litterature, des details sont donnes sur les caracteristiques et les antecedents des races ou types individuels. On analyse egalement les facteurs menaçant I’existence de ces races et leur diversite genetique. AGRI 10 48 1.0 INTRODUCTION The one-humped or dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius) reaches the eastern limit of its continuous distribution area in the Indian subcontinent. With 1.1 million head, India has the third largest camel population in the world; the majority of these are in Rajasthan (70.1 %), with much smaller numbers in Haryana (11.2%), Gujarat (7.0%), Punjab (5.9%) and the rest in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh (K:HANNA et al.,1990). -

Desert Oasis the Plants and Gardens of Western Rajasthan

Desert Oasis The Plants and Gardens of Western Rajasthan September 28 - October 13, 2016 Pennsylvania Horticultural Society 100 N. 20th Street – 5th Floor Philadelphia, PA 19103-1495 215.988.8800 PHSonline.org Dear PHS Members and Friends, Join PHS for this in-depth exploration of the horticulture and gardens of the Thar desert of Western Rajasthan. This arid expanse of over 77,000 square miles forms a natural boundary between India and Pakistan and was once ruled by the Great Desert Kingdoms of Jodhpur, Jaisalmer and Bikaner. Our trip will include visits to several, newly-restored Rajput palace gardens and their protective fortifications. A highlight of the trip will be a private tour of the Rao Jodha Desert Rock Park in Jodhpur. This unique project was first conceived by the Mehrangarh Museum Trust in 2006 as a way to restore the natural ecology of the area around Mehrangarh Fort. The 175-acre park opened for visitors in 2012, and today contains over 300 species of trees, shrubs, vines, herbs, grasses and sedges. Our trip also includes a visit to the National Research Center on Camel, which breeds a large percentage of the “Ships of the Desert” found in India, including those used by the Indian Army. A desert animal safari and two nights in a luxury tented camp set among the sand dunes will also be offered. Our tour will end in elegant Udaipur, home to the Jag Niwas and Jag Mandir floating palace gardens, just in time for the annual Hindu festival of Dussehra. Allison Rulon-Miller, the Founder of From Lost to Found Travel in Philadelphia, who designed our sold-out trip to South India in 2013, created this itinerary to highlight a different region of this remarkable country. -

9.Balak Ram Final

Journal of Global Resources Volume 2 January 2016 Page 68-75 ISSN: 2395-3160 (Print), 2455-2445 (Online) 9 APPRAISAL OF LAND USE AND AGRICULTURE SYSTEM IN ERSTWHILE BIKANER STATE OF RAJPUTANA Balak Ram 1 and J.S. Chauhan 2 1Principal Scientist (Retd.) Central Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur, India 2Chief Technical Officer, Central Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur, India Email: [email protected] Abstract: Established in 1488 by Rao Bika, Bikaner the second largest Princely State in Rajputana occupies 60585 Km 2 areas and ruled by Rathore clan of Rajput. Presently it consist the districts of Bikaner, Ganganagar, Hanumangarh and Churu. The present study focuses the situation of land use and agriculture prevalent in those days under feudal system. The role of crucial land tenure and land revenue systems; hot desertic condition and famine; political system of Mughals and British; and long driven wars, are discussed. Besides, the post independence land reforms and development of land use and agriculture are also highlighted. ‘Jagir’ and ‘Khalsa’ were predominant land tenure system. Peasants were subject to so many taxes, cess, begar and services. Of total reporting area (1898-99 to 1906-07) net cropped area constitute just 16.4 percent, current fallow 8.8 percent and culturable waste 73 percent. Irrigation was almost unknown. Only selected rainfed crops viz. bajra, jowar, moth, guar and sesame were produced. After independence Jagirdari and Jamindari systems were abolished and land reforms were introduced. With the introduction of canal irrigation, the region witnessed remarkable development in agriculture. Peoples are settled and desertification processes are checked to a considerable level. -

Tour of Rajasthan

Tour offj Rajasthan Forts, Museums, Palaces, Havelis, Religious Shrines, Horse Ride, Camel Ride, Cuisine & various Sights and Sounds Rajjpasthan Tourist Hotspots •Jaipur •Jodhpur •Jaisalmer •Udaipur •Ranakpur •Bikaner •Mt Abu •Ajmer •Bharatpur •Bundi •Kota •OiOsiyan •Alwar •Shekawati •Chittor •Ahar •Nagaur •Kichan •Abhaneri Chittorgarh Fort • Founded by Bappa Rawal of Sisodia Family. • Built in 8th Century. • City: Chittor. • Significance: History of UddUnprecedented Bravery. • Highlights: Rampol, Chattris, Suraj pol, Ranakumbha Palace, Padmini Palace. Jaigarh Fort •Founded by Maharaja Jai Singh. • Built in 1726. • City: Jaipur. • Significance: Never been captured in Battle. • Highlights: All sights intact including World’ s largest Cannon, Cannon Foundry, Temples & Towers Mehrangarh Fort • Founded by Maharaja Man Singh. • Bu ilt in 1806. • City: Jodhpur. • Significance: Heavily Fortified/Steep Structure made it difficult for capture. • Highlights: Moti Mahal, Sukh Mahal, Phool Mahal, Chamunda Devi Temple Jaisalmer Fort • Founded by Rajput Jaisala. • Built in 1156. • City: Jaisalmer. • Significance: One of the Largest Forts in the world • Highlights: Fort over 80 mt high Trikuna Hill; Still a living FtFort; RRloyal PPlalace, JiJain Temples, Laxminath Temple & 4 Massive Gates. Junagarh Fort • Founded by Rao Bika. • Built in 1478 and latter addition until 1943. • City: Bikaner. • Significance: The only major Rajasthani fort not built on a hill-top. • Highlights: Blend of Contemporary, Old, Local and Universal Architecture. Kumbalgarh Fort • Founded by Maharana Khumbha. • Built in 15th Century. • City: Rajsamand District. • Significance: Never been captured in Battle due to its enormous Fort AhittArchitecture. BithlBirthplace of Maharana Pratap. • Highlights: 36 Kms Fort Wall stretch, 360 Temples, Gardens, Baoris, 700 Cannon Bunkers, etc. Havelis Havelis mainly in Shekawati District • Haveli Nadine Prince – Fatehpur. -

Junagarh Fort - Overview Junagarh Fort, Previously Known As Chintamani, Is Situated in Bikaner

COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – MONUMENTS 0 7830294949 Junagarh Fort - Overview Junagarh Fort, previously known as Chintamani, is situated in Bikaner. Karan Chand, the prime minister of Raja Rai Singh, supervised the construction of the fort. The construction of the fort was started in 1589 and ended in 1594. The fort was attacked many times and only Kamran Raza, son of Mughal Emperor Babur, was able to win it and that too for one day only. At that time, Bikaner was ruled by Rao Jait Singh. The fort includes palaces, temples, gates and many other structures. Bikaner Bikaner is a city of Rajasthan state situated in the northwest. The city was founded by Rao Bika in 1486AD. Bikaner was previously a forest area and was known as Jangladesh. His father Maharaja Rao Jodha founded the city of Jodhpur. Rao Bika has the ambition of having his kingdom rather inheriting it or the title of Maharaja from his father. So he built the city of Bikaner at Jangladesh. In 1478, he built a fort which ruined. After 100 years, Junagarh fort was constructed. THANKS FOR READING – VISIT OUR WEBSITE www.educatererindia.com COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – MONUMENTS 0 7830294949 Visiting Hours Junagarh Fort is opened for the public at 10:00am and closed at 4:30pm. The fort is opened on all days of the week including government holidays. It takes around two to three hours to visit the whole fort as there are many structures inside that the tourists can visit. Ticket Tourists have to pay an entry fee to visit Junagarh Fort. -

The Magic of Rajasthan Tour Packages Is Unparallel in the World

The magic of Rajasthan Tour Packages is unparallel in the world. Rajasthan is the land of Kings. With invincible forts, magnificent palaces and serene lakes Rajasthan is truly called a land of valiance. Travel to Rajasthan to experience its rich heritage, history and culture, art and architecture of forts and palaces, languages, religions, folk dance and music, fairs and festivals, wildlife etc. Our Rajasthan tour packages give you a true experience of the history and culture of Rajasthan. Our Rajasthan Tours are well-planned with great sightseeing of the travel destinations in Rajasthan, luxury hotels, comfortable and luxury cars and coaches, multi language speaking guide etc. So book our Rajasthan Travel Package to enjoy a life-time experience. Duration : 15 Days & 16 Nights Destinations Covered : Delhi - Agra - Jaipur - Khimsar - Bikaner - Bikaner - Jaisalmer - Jodhpur - Ranakpur - Udaipur - Kota - Pushkar - Delhi Day 1 - In Delhi Arrive Delhi On arrival meeting and assistance at the airport and transfer to Vasant Continental Hotel (5*). Overnight at hotel. Day 2 - Delhi – Agra (200 KM.) After breakfast drive to Agra via sightseeing of Akbar’s Tomb at Sikandra. Afternoon sightseeing of Taj Mahal, Agra Fort & Itmad-Ud-Daula’s tomb. Dinner and Overnight at hotel Jaypee Palace. Day 3 - Agra – Jaipur (235 KM.) Drive to Jaipur after breakfast via sightseeing of Fathepur Sikri Fort. Arrive Jaipur in the afternoon. Evening see Rajasthani folk dance & Pupet Show. Dinner and Overnight at Samode Haveli ( Heritage Hotel). Day 4 - In Jaipur Full day sightseeing of Jaipur visit places Amber Fort and climb fort on Elephant back, Jaigarh Fort, City Palace, Museaum, Observatory and Palace of wind.