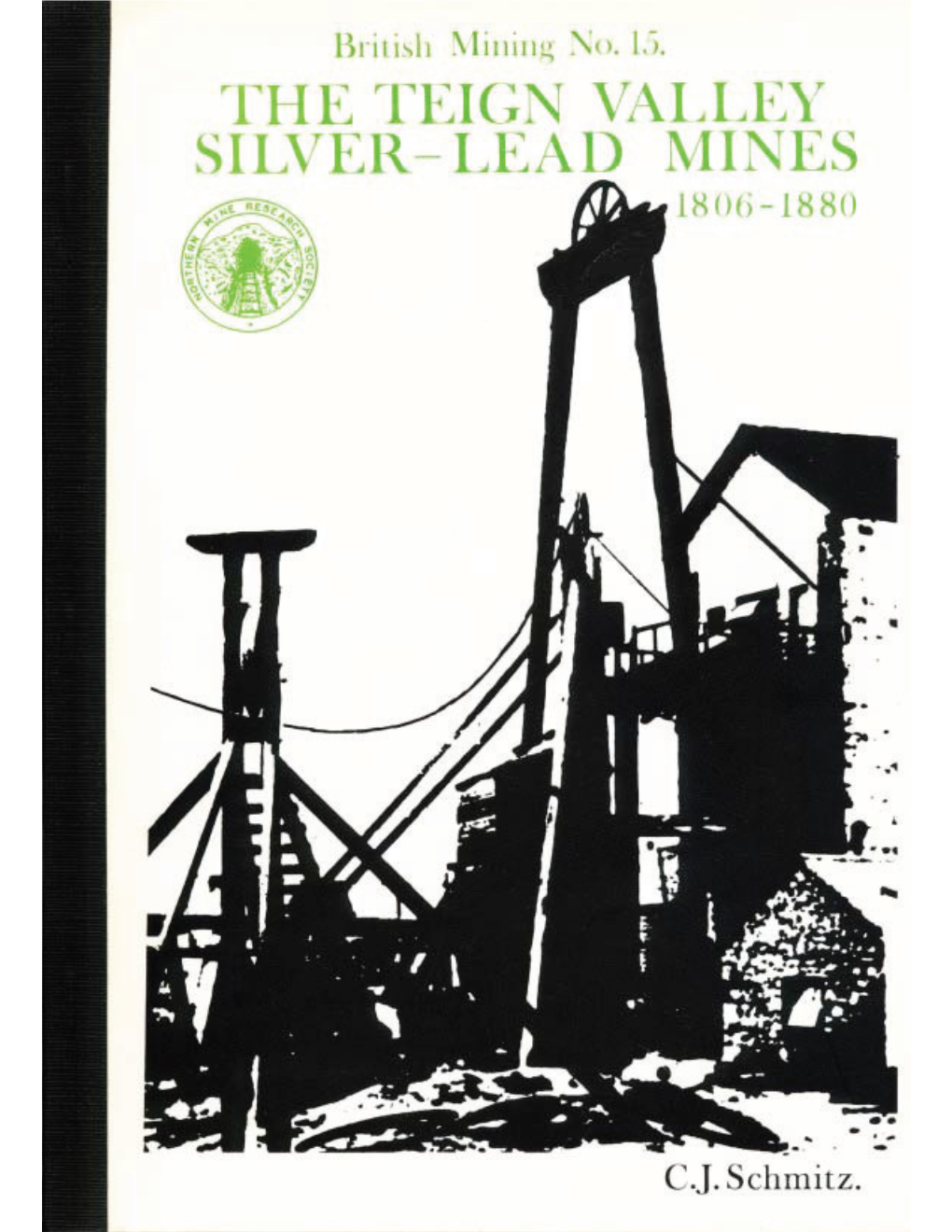

The Teign Valley Silver-Lead Mines 1806-1880

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Around the Local Neighbourhood

The Oaks Chudleigh lindenhomes.co.uk TEDBUM A CLYST 11 12 3 ST MARY PATHFINDER 77 HONITON VILLAGE A30 EXETER A30 10 CLYST LONGDOWN ST MARY 5 IDE M DUNSFORD TOPSHAM EXMINSTER A 3 7 6 KENNFORD KENN 6 HIGHER ASHTON KENNICK RESERVOIR LYMPSTONE DARTMOOR 8 5 8 7 A3 STARCROSS 0 8 EXMOUTH 3 A 1 ASHCOMBE CHUDLEIGH 4 3 9 DAWLISH WARREN BOVEY TRACEY 2 CHUDLEIGH KNIGHTON DAWLISH Around the local neighbourhood 1 Chudleigh local shops 5 Exeter Racecourse 9 Devon Guild of Craftsmen 2 Ugbrooke House and Gardens 6 Haldon Forest Park 10 Exeter Cathedral and Quayside 3 Ashcombe Adventure Centre 7 Canonteign Falls 11 Exeter Airport 4 Chudleigh Swimming Pool 8 Teign Valley Golf Club and Hotel 12 Exeter St Davids Train Station Linden Homes, South West region Heron Road, Sowton Industrial Estate, Exeter, Devon EX2 7LL. T: 01392 344700 Produced by the Vistry Group Design Studio. DCHUD GD60045 / 08.21 lindenhomes.co.uk The Oaks Chudleigh Our stunning collection of 2, 3 and 4 bedroom homes in the historic town of Chudleigh. The Oaks offers modern living at its finest. This stylish The Oaks is well connected, with Exeter just a 20 minute drive development - our signature Linden Collection range of 2,3 and away via the A38 Devon Expressway, while the same road will 4 bedroom homes - blends the tranquility of village life with all take you to Dartmoor National Park. For rail travel, Newton the conveniences of nearby city of Exeter. Abbot train station is 7 miles away and offers services to Exeter (30 minutes), Plymouth (40 minutes) and London Paddington (2 The charming town of Chudleigh has a post office, pharmacy, hours 40 minutes). -

Land at Canonteign Barton, Christow, Exeter EX6 7NS 1 *GUIDE PRICE £5,000+

LOT Land at Canonteign Barton, Christow, Exeter EX6 7NS 1 *GUIDE PRICE £5,000+ A parcel of amenity land situated at Canonteign, which has previously been utilised for parking. LOCATION NOTE The historic Tything of Canonteign is situated Please be advised that the property has a in the parish of Christow, near Chudleigh in public footpath running along its Northern South Devon, in the valley of the River Teign, boundary being public footpath 17 (Christow) renowned for the spectacular Canonteign leading down to the River Teign. Please refer Falls waterfall. to the local search within the legal pack for absolute clarification of where the path lies DESCRIPTION and the title plan for the definitive boundaries An interesting opportunity to acquire a parcel of the land. The legal pack will be available of land situated just off the B3193 heading to download free of charge from our website North towards Christow. The land has www.propertyauctionsouthwest.co.uk. recently been utilised as a parking area and is situated in proximity of Teign Valley Golf Club NOTE and Canonteign Falls. The land may well lend This property will not be sold prior to itself, subject to any requisite consents, for auction. occasional recreational camping/caravanning from which to enjoy the beautiful Teign valley and Dartmoor National Park. EPC Energy Efficiency Rating – Exempt AUCTION VALUER Wendy Alexander VIEWING At any reasonable time during daylight hours and at the viewers own risk. General information Countrywide Property Auctions 01395 275691. Guide Price definitions can be found on page 3 www.countrywidepropertyauctions.co.uk Don’t forget your proof of identity on the day: see page 5 7. -

ROGER COLLICOTT BOOKS Tel. 01364 621324 CATALOGUE

ROGER COLLICOTT BOOKS INGLEMOOR, WIDECOMBE-IN-THE-MOOR, DEVON. TQ13 7TB Tel. 01364 621324 Email : [email protected] Website : www.rogercollicottbooks.com ========= Postage charged at cost. Payment by 30 day invoice, cash, cheque, bank transfer, Paypal all very welcome. Please note we no longer except credit cards except through the website. ======== CATALOGUE 100 CORNWALL AND DEVON COMBINED 1] ANON. " Views of Cornwall and Devon and Notices of St. Michael's Mount and Dartmoor " ... [so Titled in manuscript]. Articles on Cornwall and Devon, Some extracted from the " Illustrated English Magazine.". Stout 4to.Fine. 1895. GRANGERISED COPY EXTRA-ILLUSTRATED with the addition of maps, and many prints of Cornwall and Devon. Contemporary pebble grained bevelled morocco, all edges in gilt. Lithographs, copper and steel engravings (some quite unusual prints). The Cornwall section is based around Mrs. Craik's, An Unsentimental Journey Through Cornwall, published in 1884. The Devon section includes, Among the Western Song-Men, By S. Baring Gould. Several scarce maps including : Van Den Keere, Cornwaile (1627); Morden, Robert, Cornwall, (1695); Scilly I, (not identified) (c 17th cent); Cruchley's County Map of Cornwall; Van Den Keere, Devonshire (1627); Chart of the English Channel, also a Chart of Plymouth Sound (1782); Cruchley's County Map of Devon. A splendid carefully put together collection. £400.00 2] BACON, John. Diocese of Exeter ... [ Extract from Liber Regis ]. (London): John Nichols, 1786. First Edit. 4to. Good. Rebound extract from Liber vel Thesaurus Rerum Ecclesiasticarum, the whole portion relating to the Diocese of Exeter. Pages 242 - 318, with various introductory pages and appendix. Inc. additional folding maps of Devon by W. -

Canonteign Barton CANONTEIGN • TEIGN VALLEY • D Evon

Canonteign Barton CANONTEIGN • TEIGN VALLEY • D evon Canonteign Barton CANONTEIGN • TEIGN VALLEY • D evon Exeter 10 miles (London Paddington 2 hours) • Bovey Tracey 4 miles • A38 dual carriageway 4 miles (Distances and times approximate) An outstanding large family home and cottage of the highest order throughout in a delightful valley location Accommodation and Amenities Entrance hall • Drawing room • Sitting room • Dining room • Kitchen/breakfast room • Boot room • Billiard and games room Master bedroom suite with bathroom and dressing room • 6 further bedrooms • 3 bathrooms Upstairs sitting room • Office and study Indoor swimming pool • Gym • Sauna Garaging and stores Separate 2 bedroom cottage with open plan kitchen and sitting room Attractive gardens • Summerhouse • Extensive parking In all about 2.5 acres (1.01 hectares) Knight Frank LLP Knight Frank LLP 19 Southernhay East 55 Baker Street Exeter, Devon, EX1 1QD London, W1U 8AN Tel: +44 1392 423111 Tel: +44 20 7861 1098 [email protected] [email protected] www.knightfrank.com These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the brochure. Situation • Canonteign Barton occupies a lovely position within Christow has an excellent primary school, shop, post • Communications are ideal with the fastest trains the boundary of the Dartmoor National Park and in office, a doctor’s surgery and pub. The market town from Exeter St Davids Station taking about 2 hours the attractive Teign Valley, only 10 miles from Exeter. of Bovey Tracey is about 7 miles away with good day to London Paddington. -

Lowell Libson Limited

LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 LOWELL LIBSON LIMITED BRITISH PAINTINGS WATERCOLOURS AND DRAWINGS 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · [email protected] www.lowell-libson.com LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 Our 2010 catalogue includes a diverse group of works ranging from the fascinating and extremely rare drawings of mid seventeenth century London by the Dutch draughtsman Michel 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf van Overbeek to the small and exquisitely executed painting of a young geisha by Menpes, an Australian, contained in the artist’s own version of a seventeenth century Dutch frame. Telephone: +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · Email: [email protected] Sandwiched between these two extremes of date and background, the filling comprises Website: www.lowell-libson.com · Fax: +44 (0)20 7734 9997 some quintessentially British works which serve to underline the often forgotten international- The gallery is open by appointment, Monday to Friday ism of ‘British’ art and patronage. Bellucci, born in the Veneto, studied in Dalmatia, and worked The entrance is in Old Burlington Street in Vienna and Düsseldorf before being tempted to England by the Duke of Chandos. Likewise, Boitard, French born and Parisian trained, settled in London where his fluency in the Rococo idiom as a designer and engraver extended to ceramics and enamels. Artists such as Boitard, in the closely knit artistic community of London, provided the grounding of Gainsborough’s early In 2010 Lowell Libson Ltd is exhibiting at: training through which he synthesised -

Devon – Part Two

Destination focus – Devon – part two In this second part* of our look at group friendly attractions in Devon, Stuart Render discovers more surprises, and nds out just what the Victorians did for us OCTOBER 2015 OCTOBER 21 Destination focus – Devon – part two Buckfastleigh, home of the South Bygones has surprises around every corner of the three-oor attraction, including this particularly grisly Older visitors will revel in Bygones’ Devon Railway tableau depicting a 19th-century dentist. It’s not for the faint hearted extensive collection of items Rural charm at Buckfastleigh station. A full-size Victorian Street is the centrepiece of Bygones, a privately-owned museum packed with Bygones is housed in an old cinema in the It’s not a sign you’re going to see anywhere else, but it exemplies the eclectic mix of things Most journeys will start here hundreds of thousands of items painstakingly collected by Richard Cuming and his family St Marychurch area of Torquay to see at Bygones. The present location was acquired to house a 27-ton steam locomotive evon is well known for its country lanes, its there’s more to a visit than just the opportunity to see the waterfalls Access is along the B3193 near Christow, three miles from the A38 hammers in the blacksmith’s forge and turning clay in the pottery. picturesque villages and its sandy beaches. A visit and the woodland. Teign Valley turn-o at Chudleigh. There’s an opportunity to visit the historic wooden sailing ketch to Canonteign Falls brings a new surprise: ‘England’s “We have a total of seven lakes that provide a fascinating walk in Garlandstone and, should the mood take you, to try on costumes and Highest Waterfall’, the sign says. -

Haldon's Hidden Heritage

Haldon’s Hidden Heritage The Haldon Hills – whose name may be derived from the Old English Haw-hyll dun, meaning ‘look-out hill’ – are often referred to as the ‘hidden’ hills of Devon. Apart from its forests and landmark tower, most people know little of its rich heritage. This unique exhibition touches every aspect of the Hills, through geology and prehistory, to the establishment of its grand country mansions. The panels are available to be shown in local community and school halls. 1 Supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund, with help from Arts Council England, Devon County Council, the Royal Albert Memorial Museum and the Forestry Commission. Organisation Centre for Contemporary Art and the Natural World Haldon Forest Park, Exeter EX6 7XR E: [email protected] T: 01392 832277 www.ccanw.co.uk Teignbridge D ISTRICT COUNCI L South Devon Research Iain Fraser, assisted by Christopher Pidsley and Dr. Ted Freshney. Panel design Northbank, Bath CCANW and its researchers would like to thank the numerous individuals and organisations for their generous help in assembling this exhibition. Do you have any interesting material related to Haldon’s heritage? If so, we would be interested 1 Haldon Belvedere from the air. in hearing from you. Photograph Terry Squire Haldon’s Rocks – clues to a past world The rocks of the Haldon Hills tell a story stretching back over 360 million years to times when there were mountains, deserts and tropical seas near where we stand today. The maps below show the distribution of these rocks around and on Haldon. 1 The geological history of the area around Haldon Hills B Britain Technologies-NextMAP Intermap of courtesy image Height 2008. -

Lyneham Coombe Lyneham Coombe Teign Valley, TQ13 0EH Exeter 12 Miles Chudleigh 2 Miles Dartmoor 5 Miles

Lyneham Coombe Lyneham Coombe Teign Valley, TQ13 0EH Exeter 12 miles Chudleigh 2 miles Dartmoor 5 miles • Stunning contemporary house • Delightful woodland valley setting • Over 3,700q ft of versatile accommodation • 5 Bedrooms, 4 Bathrooms • Amazing reception areas • Designed for low carbon footprint living • Triple garage • Informal grounds of 2 acres Guide price £950,000 SITUATION The property occupies a magical setting in its own wooded valley, standing at the end of a private drive. Despite its rural location close to the eastern fringes of the Dartmoor National Park, the property is only 2 miles from the attractive old town of Chudleigh, whilst more extensive facilities are found at Exeter (12 miles), Newton Abbot (9 miles) and Torquay (14 miles). The A38 linking to the M5 motorway is a short drive away. A stunningly impressive Architect-designed eco house in a wooded INTRODUCTION Lyneham Coombe is an Architect-designed modern timber and location with easy access to the A38 glass residence with some truly impressive double and triple volume entertaining spaces, which has been designed and constructed to provide an environmentally friendly and sustainable lifestyle. The house was built in 2007 and occupies approximately 200sq m on plan offering approximately 350sq m of accommodation over two floors. The design was inspired by the late Bengt Warne, an internationally renowned Swedish architect and early eco-warrior. A SUSTAINABLE LIFESTYLE The frame of the house is constructed of laminated timber beams which is infilled with glass and timber panels and the exterior is clad with Western Red Cedar capped with a cedar shingle roof. -

The Panorama of Torquay, a Descriptive and Historical Sketch Of

(f •••*. ( ; I o _- I ° & j^ ®; Sfc *-% (£>> '4 jk, '^i 0F>> wnt. onStont fy m)^Tm,^m$i toiEJssra's ©j^nsm^i PuilTSted^y E . C ocfcr em , Torofu.a-y. THE PANORAMA OF TORQUAY, DESCRIPTIVE AND HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE DISTRICT COMPRISED BETWEEN THE DART AND TEIGN, BY OCTAVIAN BLEWITT. ^ecmrtr ©fctttfliu EMBELLISHED WITH A MAP, AND NUMEROUS LITHOGRAPHIC AND WOOD ENGRAVINGS. 3Utllf0tt SIMPKIN AND MARSHALL, AND COCKREM, TORQUAY. MDCCCXXXII. ; — Hie terrarura mihi prseter omnes Angulus ridet, ubi non Hymetto Mella decedunt, viridi que certat Bacca Venafro ; Ver ubi longum, tepidas que praebet Jupiter brumas. Hor. Car : Lis. 11. 6, These forms of beauty have not been to me As is a landscape in a blind man's eye But oft in lonely rooms, and mid the din Of crowds and cities, I have owed to them. In hours of weariness, sensations sweet, Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart, And passing even unto my purer mind With tranquil restoration. Wordsworth. v. entorrtr at gztztitititx!? %att. n ^ TO HENRY WOOLLCOMBE, Esq. Clje \Bvesitismt, AND TO THE OTHER MEMBERS OP THE PLYMOUTH ATHENAEUM, THIS ATTEMPT TO ILLUSTRATE ONE OP THE MOST BEAUTIFUL DISTRICTS OF £0uti) Btban, IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED, WITH THE AUTHOR'S BEST WISHES FOR THE INCREASING PROSPERITY OF €f)Z Iitftttuttfftu PREFACE. In presenting to the public a new edition of this Sketch, a few words may, perhaps, be expected from me ; and I offer them the more willingly since it is my duty to acknowledge here the sources of my information. The following pages have been wholly re-written, and now contain more than ten times as much matter as the first Edition,—although that impression has been twice pirated. -

Start Point See the Website For: Attractions - Events - Online Discounts - Competitions - News

Lundy Island i Lynmouth Be inspired for a fabulous SWCP Lynton 5 A39 A399 Combe Martin A39 day out at Devon’s award Lee i Ilfracombe Mortehoe winning attractions Woolacombe A3123 A361 6 A39 Croyde Key to Map Saunton Braunton A399 Major roads - A classification A361 SWCP Heritage, Houses & Gardens i Barnstaple Tarka Trail River Taw Estuary SWCP Major roads - B classification Instow 1. Clovelly Village ................................... EX39 5TA A361 Long Distance Footpath Westward Ho A39 4. Dartington Crystal ............................ EX38 7AN Hartland Areas of Outstanding SWCP Point 3 i Bideford 9. Killerton House ...................................... EX5 3LE 7 2 MOORS WAY Natural Beauty (AONB) Clovelly Hartland 10. Coldharbour Mill & Country Park ....EX15 3EE 1 i South Molton National Parks A377 16. Bicton Park Botanical Gardens .........EX9 7BG A39 2 Villages / small towns Mortehoe 21. Exeter Cathedral ...................... ............EX1 1HS A388 4 i Great 23. Castle Drogo.......................................... EX6 6PB Torrington Tarka rail link Area centres Braunton 26. Bygones ..................................................TQ1 4PR Larger towns, showing 2 MOORS WAY approximate extent of Barnstaple 28. Kents Cavern ...........................................TQ1 2JF Tarka Trail built up area. A386 A3124 10 i Tiverton 31. Morwellham Quay ................................PL19 8JL Tourist Information Centres i A388 A377 11 A303 35. Buckfast Abbey .................................. TQ11 0EE Tourist Attraction (colour shows 8 Cullompton type of attraction. See Key to 0 A3072 Devon’s Top Attractions above). Activity Centres Morchard Bishop i A373 Holsworthy Hatherleigh A30 33. River Dart Adventures ..................... TQ13 7NP A3072 A3072 A377 A396 A3072 i Crediton A386 Theme Parks & Farms A388 9 Axminster 12 i Honiton A35 2. The Milky Way Adventure Park .... *EX39 5RY Tarka Trail i A375 Okehampton Exeter 3. -

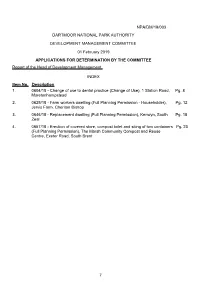

01 February 2019 Reports

NPA/DM/19/003 DARTMOOR NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE 01 February 2019 APPLICATIONS FOR DETERMINATION BY THE COMMITTEE Report of the Head of Development Management INDEX Item No. Description 1. 0604/18 - Change of use to dental practice (Change of Use), 1 Station Road, Pg. 8 Moretonhampstead 2. 0625/18 - Farm workers dwelling (Full Planning Permission - Householder), Pg. 12 Jervis Farm, Cheriton Bishop 3. 0646/18 - Replacement dwelling (Full Planning Permission), Kenwyn, South Pg. 18 Zeal 4. 0657/18 - Erection of covered store, compost toilet and siting of two containers Pg. 23 (Full Planning Permission), The Marsh Community Compost and Reuse Centre, Exeter Road, South Brent 7 8 1. Application No: 0604/18 District/Borough:Teignbridge District Application Type: Change of Use Parish: Moretonhampstead Grid Ref: SX753860 Officer: Nicola Turner Proposal: Change of use to dental practice Location: 1 Station Road, Moretonhampstead Applicant: Dr S Channing Recommendation That permission be GRANTED Condition(s) 1. The development hereby permitted shall be begun before the expiration of three years from the date of this permission. 2. The premises hereby approved shall only be used for Class D1 Clinic use in accordance with the Schedule to the Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) Order 1987, or in any provision equivalent to that Class in any statutory instrument revoking and re-enacting that Order with or without modification. 3. The change of use shall apply to the building identified on thesite location plan received 31 October 2018. Introduction The site is the former Lloyds bank on the corner of Station Road/Cross Street in the centre of the village. -

Chudleigh | Devon Five Bespoke Detached Family Homes

Chudleigh | Devon Five bespoke detached family homes. Chudleigh is perfectly nestled between the South Devon Coast and Dartmoor National Park The small traditional town of Chudleigh dates back to The town has all the services you require from a post Iron Age times with a well-defined early Iron Age hill office, butchers and greengrocer to a doctors surgery, fort to the south east of the town. The town sits east dentist and vetenary practice. There are a few public of the River Teign on the south west side of the Haldon houses to choose from, offering locally produced Hills. With the A38 easily accessible, both Exeter and ales and food. Chudleigh hosts a summer and winter Plymouth are just a short drive away in either direction. carnival and late night Christmas shopping festival, all A flourishing main street through the town has a of which are heavily supported by the local and wider wealth of local trades offering from everyday grocery communities. People who settle in Chudleigh enjoy items to the more unusual gift or craft item. the knowledge that the local authorities, residents and businesses all work together to make Chudleigh a 21st Century town. A complete lifestyle... ...on your doorstep Whatever your lifestyle, Brookfield is perfectly placed The coast is approximately 15 minutes drive. for the things you love. Just a short drive away is the Teignmouth and Dawlish are excellent seaside towns bustling city of Exeter, perfect for a spot of retail therapy where you can fish, sail or just stroll along the beach and a spot of lunch.