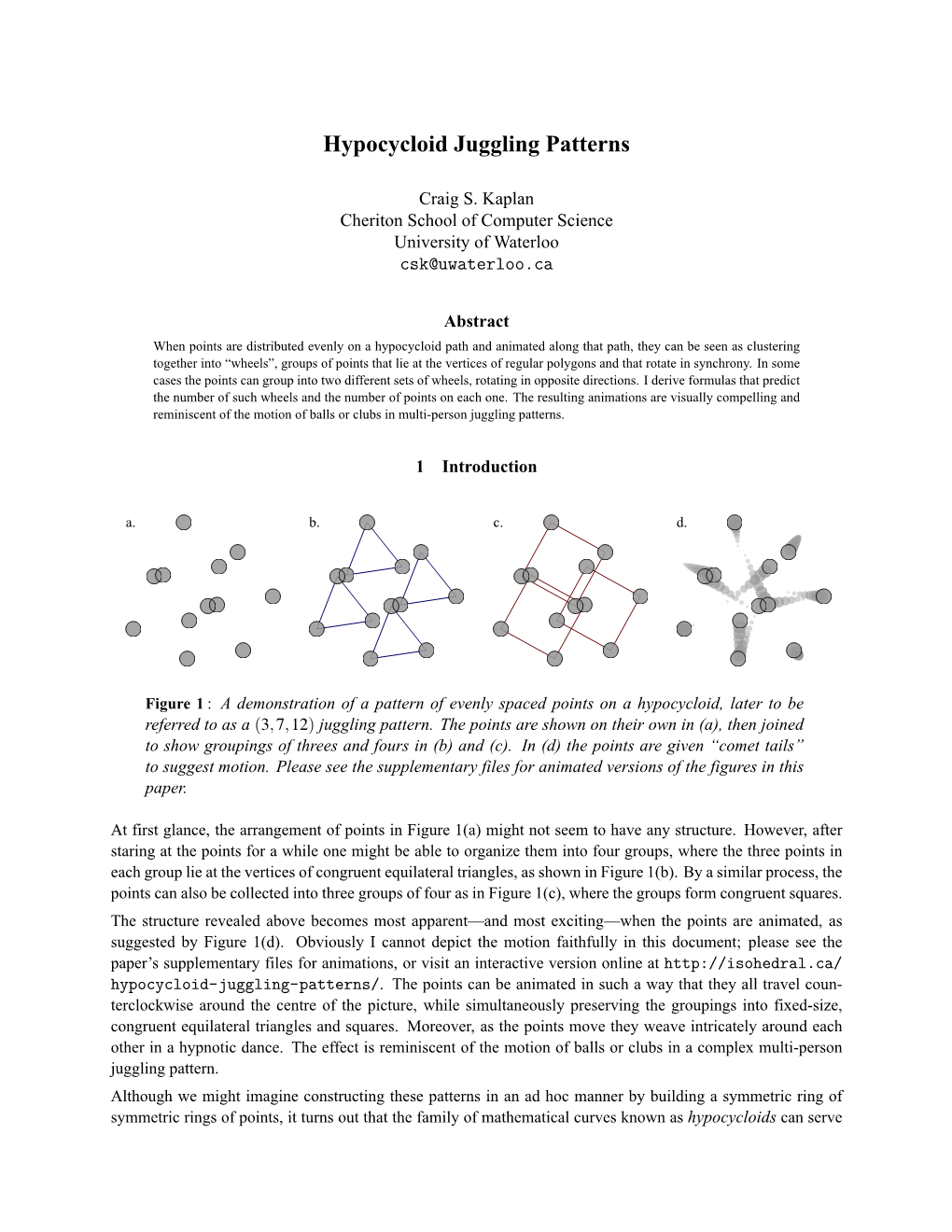

Hypocycloid Juggling Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polar Coordinates and Complex Numbers Infinite Series Vectors and Matrices Motion Along a Curve Partial Derivatives

Contents CHAPTER 9 Polar Coordinates and Complex Numbers 9.1 Polar Coordinates 348 9.2 Polar Equations and Graphs 351 9.3 Slope, Length, and Area for Polar Curves 356 9.4 Complex Numbers 360 CHAPTER 10 Infinite Series 10.1 The Geometric Series 10.2 Convergence Tests: Positive Series 10.3 Convergence Tests: All Series 10.4 The Taylor Series for ex, sin x, and cos x 10.5 Power Series CHAPTER 11 Vectors and Matrices 11.1 Vectors and Dot Products 11.2 Planes and Projections 11.3 Cross Products and Determinants 11.4 Matrices and Linear Equations 11.5 Linear Algebra in Three Dimensions CHAPTER 12 Motion along a Curve 12.1 The Position Vector 446 12.2 Plane Motion: Projectiles and Cycloids 453 12.3 Tangent Vector and Normal Vector 459 12.4 Polar Coordinates and Planetary Motion 464 CHAPTER 13 Partial Derivatives 13.1 Surfaces and Level Curves 472 13.2 Partial Derivatives 475 13.3 Tangent Planes and Linear Approximations 480 13.4 Directional Derivatives and Gradients 490 13.5 The Chain Rule 497 13.6 Maxima, Minima, and Saddle Points 504 13.7 Constraints and Lagrange Multipliers 514 CHAPTER 12 Motion Along a Curve I [ 12.1 The Position Vector I-, This chapter is about "vector functions." The vector 2i +4j + 8k is constant. The vector R(t) = ti + t2j+ t3k is moving. It is a function of the parameter t, which often represents time. At each time t, the position vector R(t) locates the moving body: position vector =R(t) =x(t)i + y(t)j + z(t)k. -

Arts Revealed in Calculus and Its Extension

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265557431 Arts revealed in calculus and its extension Article · August 2014 CITATIONS READS 9 455 1 author: Hanna Arini Parhusip Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana 95 PUBLICATIONS 89 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Pusnas 2015/2016 View project All content following this page was uploaded by Hanna Arini Parhusip on 16 September 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. [Type[Type aa quotequote fromfrom thethe documentdocument oror thethe International Journal of Statistics and Mathematics summarysummary ofof anan interestinginteresting point.point. YouYou cancan Vol. 1(3), pp. 016-023, August, 2014. © www.premierpublishers.org, ISSN: xxxx-xxxx x positionposition thethe texttext boxbox anywhereanywhere inin thethe IJSM document. Use the Text Box Tools tab to document. Use the Text Box Tools tab to changechange thethe formattingformatting ofof thethe pullpull quotequote texttext box.]box.] Review Arts revealed in calculus and its extension Hanna Arini Parhusip Mathematics Department, Science and Mathematics Faculty, Satya Wacana Christian University (SWCU)-Jl. Diponegoro 52-60 Salatiga, Indonesia Email: [email protected], Tel.:0062-298-321212, Fax: 0062-298-321433 Motivated by presenting mathematics visually and interestingly to common people based on calculus and its extension, parametric curves are explored here to have two and three dimensional objects such that these objects can be used for demonstrating mathematics. Epicycloid, hypocycloid are particular curves that are implemented in MATLAB programs and the motifs are presented here. The obtained curves are considered to be domains for complex mappings to have new variation of Figures and objects. -

On the Topology of Hypocycloid Curves

Física Teórica, Julio Abad, 1–16 (2008) ON THE TOPOLOGY OF HYPOCYCLOIDS Enrique Artal Bartolo∗ and José Ignacio Cogolludo Agustíny Departamento de Matemáticas, Facultad de Ciencias, IUMA Universidad de Zaragoza, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain Abstract. Algebraic geometry has many connections with physics: string theory, enu- merative geometry, and mirror symmetry, among others. In particular, within the topo- logical study of algebraic varieties physicists focus on aspects involving symmetry and non-commutativity. In this paper, we study a family of classical algebraic curves, the hypocycloids, which have links to physics via the bifurcation theory. The topology of some of these curves plays an important role in string theory [3] and also appears in Zariski’s foundational work [9]. We compute the fundamental groups of some of these curves and show that they are in fact Artin groups. Keywords: hypocycloid curve, cuspidal points, fundamental group. PACS classification: 02.40.-k; 02.40.Xx; 02.40.Re . 1. Introduction Hypocycloid curves have been studied since the Renaissance (apparently Dürer in 1525 de- scribed epitrochoids in general and then Roemer in 1674 and Bernoulli in 1691 focused on some particular hypocycloids, like the astroid, see [5]). Hypocycloids are described as the roulette traced by a point P attached to a circumference S of radius r rolling about the inside r 1 of a fixed circle C of radius R, such that 0 < ρ = R < 2 (see Figure 1). If the ratio ρ is rational, an algebraic curve is obtained. The simplest (non-trivial) hypocycloid is called the deltoid or the Steiner curve and has a history of its own both as a real and complex curve. -

Around and Around ______

Andrew Glassner’s Notebook http://www.glassner.com Around and around ________________________________ Andrew verybody loves making pictures with a Spirograph. The result is a pretty, swirly design, like the pictures Glassner EThis wonderful toy was introduced in 1966 by Kenner in Figure 1. Products and is now manufactured and sold by Hasbro. I got to thinking about this toy recently, and wondered The basic idea is simplicity itself. The box contains what might happen if we used other shapes for the a collection of plastic gears of different sizes. Every pieces, rather than circles. I wrote a program that pro- gear has several holes drilled into it, each big enough duces Spirograph-like patterns using shapes built out of to accommodate a pen tip. The box also contains some Bezier curves. I’ll describe that later on, but let’s start by rings that have gear teeth on both their inner and looking at traditional Spirograph patterns. outer edges. To make a picture, you select a gear and set it snugly against one of the rings (either inside or Roulettes outside) so that the teeth are engaged. Put a pen into Spirograph produces planar curves that are known as one of the holes, and start going around and around. roulettes. A roulette is defined by Lawrence this way: “If a curve C1 rolls, without slipping, along another fixed curve C2, any fixed point P attached to C1 describes a roulette” (see the “Further Reading” sidebar for this and other references). The word trochoid is a synonym for roulette. From here on, I’ll refer to C1 as the wheel and C2 as 1 Several the frame, even when the shapes Spirograph- aren’t circular. -

Additive Manufacturing Application for a Turbopump Rotor

EDITORIAL Identificarea nevoii societale (1) Fie că este vorba de ştiinţă sau de politică, Max Weber viza acelaşi scop: să extragă etica specifică unei activităţi pe care o dorea conformă cu finalitatea sa Raymond ARON Viața oricărei persoane moderne este asociată, mai mult sau mai puțin conștient, așteptării societale. Putem spune că suntem imersați în așteptare, că depindem de ea și o influențăm. Cumpărăm mărfuri din magazine mici ori hipermarketuri, ne instruim în școli și universități, folosim produse realizate în fabrici, avem relații cu băncile. Ca o concluzie, suntem angajați ai unor instituții/organizații și clienți ai altora. Toate aceste lucruri determină o creștere mai mare ca niciodată a valorii organizațiilor și a activităților organizaționale. Teoria organizației este o știință bine formată, fondator al acestei discipline fiind considerat sociologul, avocatul, economistul și istoricului german Max Weber (1864-1920) cel care a trasat așa-numita direcție birocratică în dezvoltarea teoriei managementului și organizării. În scrierile sale despre raționalizarea societății, căutând un răspuns la întrebarea ce trebuie făcut pentru ca întreaga organizație să funcționeze ca o mașină, acesta a subliniat că ordinea, susținută de reguli relevante, este cea mai eficientă metodă de lucru pentru orice grup organizat de oameni. El a considerat că organizația poate fi descompusă în părțile componente și se poate normaliza activitatea fiecăreia dintre aceste părți, a propus astfel să se reglementeze cu precizie numărul și funcțiile angajaților și ale organizațiilor, a subliniat că organizația trebuie administrată pe o bază rațională/impersonală. În acest punct, aspectul social al organizației este foarte important, oamenii fiind recunoscuți pentru ideile, caracterul, relațiile, cultura și deloc de neglijat, așteptările lor. -

On the Topology of Hypocycloids

ON THE TOPOLOGY OF HYPOCYCLOIDS ENRIQUE ARTAL BARTOLO AND JOSE´ IGNACIO COGOLLUDO-AGUST´IN Abstract. Algebraic geometry has many connections with physics: string theory, enumerative geometry, and mirror symmetry, among others. In par- ticular, within the topological study of algebraic varieties physicists focus on aspects involving symmetry and non-commutativity. In this paper, we study a family of classical algebraic curves, the hypocycloids, which have links to physics via the bifurcation theory. The topology of some of these curves plays an important role in string theory [3] and also appears in Zariski’s foundational work [9]. We compute the fundamental groups of some of these curves and show that they are in fact Artin groups. 1. Introduction Hypocycloid curves have been studied since the Renaissance (apparently D¨urer in 1525 described epitrochoids in general and then Roemer in 1674 and Bernoulli in 1691 focused on some particular hypocycloids, like the astroid, see [5]). Hypocy- cloids are described as the roulette traced by a point P attached to a circumference S of radius r rolling about the inside of a fixed circle C of radius R, such that r 1 0 < ρ = R < 2 (see Figure 1). If the ratio ρ is rational, an algebraic curve is ob- tained. The simplest (non-trivial) hypocycloid is called the deltoid or the Steiner curve and has a history of its own both as a real and complex curve. S r C P arXiv:1703.08308v1 [math.AG] 24 Mar 2017 R Figure 1. Hypocycloid Key words and phrases. hypocycloid curve, cuspidal points, fundamental group. -

Hypocycloid Motion in the Melvin Magnetic Universe

Hypocycloid motion in the Melvin magnetic universe Yen-Kheng Lim∗ Department of Mathematics, Xiamen University Malaysia, 43900 Sepang, Malaysia May 19, 2020 Abstract The trajectory of a charged test particle in the Melvin magnetic universe is shown to take the form of hypocycloids in two different regimes, the first of which is the class of perturbed circular orbits, and the second of which is in the weak-field approximation. In the latter case we find a simple relation between the charge of the particle and the number of cusps. These two regimes are within a continuously connected family of deformed hypocycloid-like orbits parametrised by the magnetic flux strength of the Melvin spacetime. 1 Introduction The Melvin universe describes a bundle of parallel magnetic field lines held together under its own gravity in equilibrium [1, 2]. The possibility of such a configuration was initially considered by Wheeler [3], and a related solution was obtained by Bonnor [4], though in today’s parlance it is typically referred to as the Melvin spacetime [5]. By the duality of electromagnetic fields, a similar solution consisting of parallel electric fields can be arXiv:2004.08027v2 [gr-qc] 18 May 2020 obtained. In this paper, we shall mainly be interested in the magnetic version of this solution. The Melvin spacetime has been a solution of interest in various contexts of theoretical high-energy physics. For instance, the Melvin spacetime provides a background of a strong magnetic field to induce the quantum pair creation of black holes [6, 7]. Havrdov´aand Krtouˇsshowed that the Melvin universe can be constructed by taking the two charged, accelerating black holes and pushing them infinitely far apart [8]. -

Engineering Curves and Theory of Projections

ME 111: Engineering Drawing Lecture 4 08-08-2011 Engineering Curves and Theory of Projection Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Guwahati – 781039 Distance of the point from the focus Eccentrici ty = Distance of the point from the directric When eccentricity < 1 Ellipse =1 Parabola > 1 Hyperbola eg. when e=1/2, the curve is an Ellipse, when e=1, it is a parabola and when e=2, it is a hyperbola. 2 Focus-Directrix or Eccentricity Method Given : the distance of focus from the directrix and eccentricity Example : Draw an ellipse if the distance of focus from the directrix is 70 mm and the eccentricity is 3/4. 1. Draw the directrix AB and axis CC’ 2. Mark F on CC’ such that CF = 70 mm. 3. Divide CF into 7 equal parts and mark V at the fourth division from C. Now, e = FV/ CV = 3/4. 4. At V, erect a perpendicular VB = VF. Join CB. Through F, draw a line at 45° to meet CB produced at D. Through D, drop a perpendicular DV’ on CC’. Mark O at the midpoint of V– V’. 3 Focus-Directrix or Eccentricity Method ( Continued) 5. With F as a centre and radius = 1–1’, cut two arcs on the perpendicular through 1 to locate P1 and P1’. Similarly, with F as centre and radii = 2– 2’, 3–3’, etc., cut arcs on the corresponding perpendiculars to locate P2 and P2’, P3 and P3’, etc. Also, cut similar arcs on the perpendicular through O to locate V1 and V1’. 6. Draw a smooth closed curve passing through V, P1, P/2, P/3, …, V1, …, V’, …, V1’, … P/3’, P/2’, P1’. -

Cycloids and Paths

Cycloids and Paths Why does a cycloid-constrained pendulum follow a cycloid path? By Tom Roidt Under the direction of Dr. John S. Caughman In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Masters of Science in Teaching Mathematics Portland State University Department of Mathematics and Statistics Fall, 2011 Abstract My MST curriculum project aims to explore the history of the cycloid curve and some of its many interesting properties. Specifically, the mathematical portion of my paper will trace the origins of the curve and the many famous (and not-so- famous) mathematicians who have studied it. The centerpiece of the mathematical portion is an exploration of Roberval's derivation of the area under the curve. This argument makes clever use of Cavalieri's Principle and some basic geometry. Finally, for closure, the paper examines in detail the original motivation for this topic -- namely, the properties of a pendulum constricted by inverted cycloids. Many textbooks assert that a pendulum constrained by inverted cycloids will follow a path that is also a cycloid, but most do not justify this claim. I was able to derive the result using analytic geometry and a bit of knowledge about parametric curves. My curriculum side of the project seeks to use these topics to motivate some teachable moments. In particular, the activities that are developed here are mainly intended to help teach students at the pre-calculus level (in HS or beginning college) three main topics: (1) how to find the parametric equation of a cycloid, (2) how to understand (and work through) Roberval's area derivation, and, (3) for more advanced students, how to find the area under the curve using integration. -

Steiner's Hat: a Constant-Area Deltoid Associated with the Ellipse

STEINER’S HAT: A CONSTANT-AREA DELTOID ASSOCIATED WITH THE ELLIPSE RONALDO GARCIA, DAN REZNIK, HELLMUTH STACHEL, AND MARK HELMAN Abstract. The Negative Pedal Curve (NPC) of the Ellipse with respect to a boundary point M is a 3-cusp closed-curve which is the affine image of the Steiner Deltoid. Over all M the family has invariant area and displays an array of interesting properties. Keywords curve, envelope, ellipse, pedal, evolute, deltoid, Poncelet, osculat- ing, orthologic. MSC 51M04 and 51N20 and 65D18 1. Introduction Given an ellipse with non-zero semi-axes a,b centered at O, let M be a point in the plane. The NegativeE Pedal Curve (NPC) of with respect to M is the envelope of lines passing through points P (t) on the boundaryE of and perpendicular to [P (t) M] [4, pp. 349]. Well-studied cases [7, 14] includeE placing M on (i) the major− axis: the NPC is a two-cusp “fish curve” (or an asymmetric ovoid for low eccentricity of ); (ii) at O: this yielding a four-cusp NPC known as Talbot’s Curve (or a squashedE ellipse for low eccentricity), Figure 1. arXiv:2006.13166v5 [math.DS] 5 Oct 2020 Figure 1. The Negative Pedal Curve (NPC) of an ellipse with respect to a point M on the plane is the envelope of lines passing through P (t) on the boundary,E and perpendicular to P (t) M. Left: When M lies on the major axis of , the NPC is a two-cusp “fish” curve. Right: When− M is at the center of , the NPC is 4-cuspE curve with 2-self intersections known as Talbot’s Curve [12]. -

An Interactive Gallery on the Internet: “Surfaces Beyond the Third Dimension”

International Journal of Shape Modeling, Vol. 0, No. 0 (1998) 000{000 c World Scienti¯c Publishing Company f AN INTERACTIVE GALLERY ON THE INTERNET: \SURFACES BEYOND THE THIRD DIMENSION" THOMAS F. BANCHOFF Department of Mathematics, Brown University Providence, RI 02912, USA and DAVIDE P. CERVONE Department of Mathematics, Union College Schenectady, NY 12308, USA Received (received date) Revised (revised date) Communicated by (Name of Editor) Originally developed as an exhibition for the Providence Art Clubs' Dodge Gallery in March of 1996, \Surface Beyond the Third Dimension" continues its existence today as a virtual experience on the internet. Here, the authors take you on a tour of the exhibit and describe both the artwork and the mathematics underlying the images, whose subjects range from projections of spheres and tori in four-space, to images of complex functions, to views of the Klein bottle. Along the way, the authors introduce some of the issues that arise from this dual presentation approach, and point out some of the enhancements available in the virtual gallery that are not possible in the physical one. Keywords: Complex functions, fourth dimension, mathematical art, surfaces, torus, Klein bottle 1. Introduction What is the best way to display a variety of surfaces so as to encourage many people to interact with them? Stage an exhibit. In March of 1996, the Providence Art Club, one of the oldest such clubs in the country, hosted the show \Surfaces Beyond the Third Dimension" in their Dodge House Gallery. The ¯rst incarnation of that exhibition lasted for two weeks, and the gallery book includes the signatures of dozens of visitors, including artists, students, and mathematicians. -

R13 – Mining Engineering

ACADEMIC REGULATIONS COURSE STRUCTURE AND DETAILED SYLLABUS 25 MINING ENGINEERING For B.TECH. FOUR YEAR DEGREE COURSE (Applicable for the batches admitted from 2013-14) (I - IV Years Syllabus) JAWAHARLAL NEHRU TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY HYDERABAD KUKATPALLY, HYDERABAD - 500 085. 2 MINING ENGINEERING 2013-14 3 MINING ENGINEERING 2013-14 ACADEMIC REGULATIONS R13 FOR B. TECH. (REGULAR) Applicable for the students of B. Tech. (Regular) from the Academic Year 2013-14 and onwards 1. Award of B. Tech. Degree A student will be declared eligible for the award of B. Tech. Degree if he fulfils the following academic regulations: 1.1 The candidate shall pursue a course of study for not less than four academic years and not more than eight academic years. 1.2 After eight academic years of course of study, the candidate is permitted to write the examinations for two more years. 1.3 The candidate shall register for 224 credits and secure 216 credits with compulsory subjects as listed in Table-1. Table 1: Compulsory Subjects Serial Number Subject Particulars 1 All practical subjects 2 Industry oriented mini project 3 Comprehensive Viva-Voce 4 Seminar 5 Project work 2 The students, who fail to fulfill all the academic requirements for the award of the degree within ten academic years from the year of their admission, shall forfeit their seats in B. Tech. course. 3 Courses of study The following courses of study are offered at present as specializations for the B. Tech. Course: Branch Code Branch 01 Civil Engineering 02 Electrical and Electronics Engineering