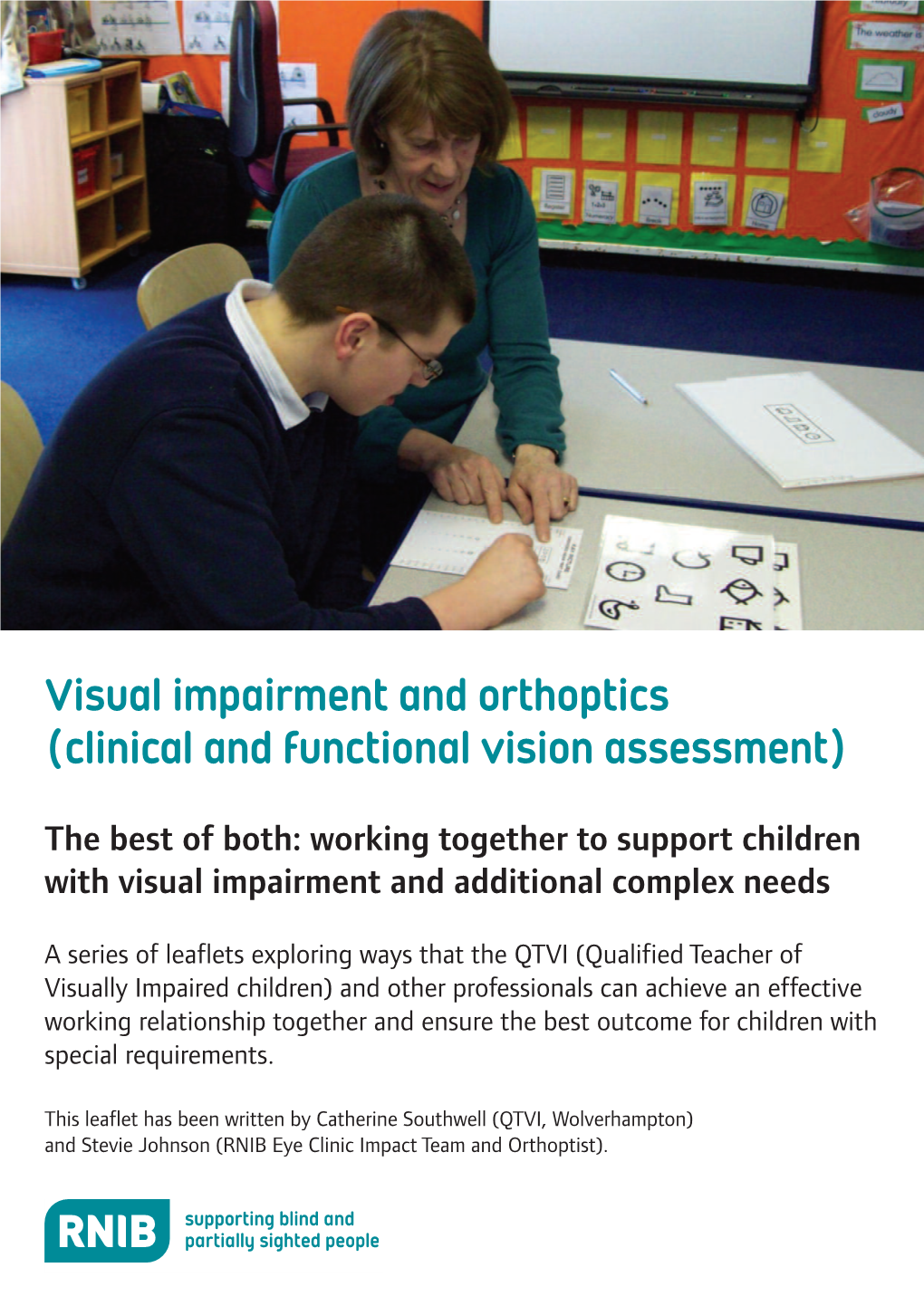

Visual Impairment and Orthoptics (Clinical and Functional Vision Assessment)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Do You Know Your Eye Care Jargon? an OPTOMETRIST

Do you know your eye care jargon? Optometrists, Orthoptists and Opthalmologists all work in the field of eye care and often work as a team in the same practice. These various professional “categories” can cause quite a lot of confusion though. Not only do they sound similarbut some of their roles can overlap, thus making the differentiation even harder. One great example is that all these experts can recommend glasses. In this article, I will aim to overview the role of each specialty and so make it easier to identify who does what! The levels of training and what they are permitted to do for youas a patientare an important differentiator between these specialties. It will definitely help you make the best-informed decision when looking for help regarding your specific eye care issue. AN OPTOMETRIST In South Africa, Optometrists need to complete a four-year Bachelor of Optometry degree before they are permitted to practice. Once qualified, they provide vital primary vision care. They conduct vision tests and eye examinations on patients in order to detect visual errors, such as near-sightedness, long-sightedness and astigmatism. Optometrists also do testing to determine the patient's ability to focus and coordinate their eyes, judge depth perception, and see colors accurately. Once a visual „problem‟ has been identified andanalyzed, the optometristeffectively corrects them and their related problems, by providing comfortable glasses and or contact lenses. They are also responsible for the maintenance of these “devices”. Optometrists also play an important role in the diagnosis and rehabilitation of patients suffering from Low-vision. -

Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction

OPTOMETRIC CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction OPTOMETRY: THE PRIMARY EYE CARE PROFESSION Doctors of optometry are independent primary health care providers who examine, diagnose, treat, and manage diseases and disorders of the visual system, the eye, and associated structures as well as diagnose related systemic conditions. Optometrists provide more than two-thirds of the primary eye care services in the United States. They are more widely distributed geographically than other eye care providers and are readily accessible for the delivery of eye and vision care services. There are approximately 36,000 full-time-equivalent doctors of optometry currently in practice in the United States. Optometrists practice in more than 6,500 communities across the United States, serving as the sole primary eye care providers in more than 3,500 communities. The mission of the profession of optometry is to fulfill the vision and eye care needs of the public through clinical care, research, and education, all of which enhance the quality of life. OPTOMETRIC CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE CARE OF THE PATIENT WITH ACCOMMODATIVE AND VERGENCE DYSFUNCTION Reference Guide for Clinicians Prepared by the American Optometric Association Consensus Panel on Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction: Jeffrey S. Cooper, M.S., O.D., Principal Author Carole R. Burns, O.D. Susan A. Cotter, O.D. Kent M. Daum, O.D., Ph.D. John R. Griffin, M.S., O.D. Mitchell M. Scheiman, O.D. Revised by: Jeffrey S. Cooper, M.S., O.D. December 2010 Reviewed by the AOA Clinical Guidelines Coordinating Committee: David A. -

Treatment of Convergence Insufficiency in Childhood: a Current Perspective

1040-5488/09/8605-0420/0 VOL. 86, NO. 5, PP. 420–428 OPTOMETRY AND VISION SCIENCE Copyright © 2009 American Academy of Optometry REVIEW Treatment of Convergence Insufficiency in Childhood: A Current Perspective Mitchell Scheiman*, Michael Rouse†, Marjean Taylor Kulp†, Susan Cotter†, Richard Hertle‡, and G. Lynn Mitchell§ ABSTRACT Purpose. To provide a current perspective on the management of convergence insufficiency (CI) in children by summarizing the findings and discussing the clinical implications from three recent randomized clinical trials in which we evaluated various treatments for children with symptomatic CI. We then present an evidence-based treatment approach for symptomatic CI based on the results of these trials. Finally, we discuss unanswered questions and suggest directions for future research in this area. Methods. We reviewed three multi-center randomized clinical trials comparing treatments for symptomatic (CI) in children 9 to 17 years old (one study 9 to 18 years old). Two trials evaluated active therapies for CI. These trials compared the effectiveness of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy, office-based placebo therapy, and home-based therapy [pencil push-ups alone (both trials), home-based computer vergence/accommodative therapy, and pencil push-ups (large-scale study)]. One trial compared the effectiveness of base-in prism reading glasses to placebo reading glasses. All studies included well-defined criteria for the diagnosis of CI, a placebo group, and masked examiners. The primary outcome measure was the Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey score. Secondary outcomes were near point of convergence and positive fusional vergence at near. Results. Office-based vergence/accommodative therapy was significantly more effective than home-based or placebo therapies. -

COMPLEMENTARY THERAPY ASSESSMENT VISUAL TRAINING for REFRACTIVE ERRORS August 2013

COMPLEMENTARY THERAPY ASSESSMENT VISUAL TRAINING FOR REFRACTIVE ERRORS August 2013 SUMMARY DESCRIPTION OF VISUAL TRAINING Vision training consists of a variety of programs designed to enhance visual efficiency and processing. Vision training, or orthoptics, typically addresses how well both eyes work together. Eye exercises may include, muscle relaxation techniques, biofeedback, eye patches, eye massages, the use of under-corrected prescription lenses, and/or nutritional supplements. Training is most often provided by an optometrist. BENEFITS One randomized controlled trial (RCT) of biofeedback training for control of accommodation for myopia reported no statistically significant benefits from training (Level I evidence). Another RCT (2013), which investigated vision training modalities to evaluate changes in peripheral refraction profiles in myopes, also found no evidence of benefits (Level 1 evidence). In other studies undertaken over the last 60 years, an improvement in subjective visual acuity (VA) in myopes with no corresponding improvement in objective VA has been reported (Level II/III evidence). RISKS The only risk attributable to visual training is financial. Most health insurers do not cover visual training programs. At the start of treatment, the optometrist should provide a reasonable estimate of what improvement to expect and how long it will take. CONCLUSIONS There is Level I evidence that visual training for control of accommodation has no effect on myopia. In other studies (Level II/III evidence), an improvement in subjective VA for patients with myopia that have undertaken visual training has been shown, but no corresponding physiological cause for the improvement has been demonstrated. It is postulated that the improvements in myopic patients noted in these studies were due to improvements in interpreting blurred images, changes in mood or motivation, creation of an artificial contact lens by tear film changes, or a pinhole effect from miosis of the pupil. -

2019 Volume 51 Evaluation of Education of Patients with AMD Of

2019 Volume 51 Evaluation of education of patients with AMD of treatment and services Gaze behaviour of novice and glaucoma specialists of optic disc examination Orthoptics Australia workforce survey 2017 2019 Volume 51 The official journal of Orthoptics Australia ISSN 2209-1262 Editors in Chief Linda Santamaria DipAppSc(Orth) MAppSc Meri Vukicevic BOrth PGDipHlthResMeth PhD Editorial Board Jill Carlton MMedSc(Orth), BMedSc(Orth) Konstandina Koklanis BOrth(Hons) PhD Nathan Clunas BAppSc(Orth)Hons PhD Linda Malesic BOrth(Hons) PhD Elaine Cornell DOBA DipAppSc MA PhD Karen McMain BA OC(C) COMT (Halifax, Nova Scotia) Catherine Devereux DipAppSc(Orth) MAppSc Vincent Ngugen BAppSc(Hons) MAppSc PhD Gill Roper-Hall DBOT CO COMT Kerry Fitzmaurice HTDS DipAppSc(Orth) PhD Sue Silveira DipAppSc(Orth) MHlthEd PhD Mara Giribaldi BAppSc(Orth) Kathryn Thompson DipAppSc(Orth) GradCertHlthScEd MAppSc(Orth) Julie Green DipAppSc(Orth) PhD Suzane Vassallo BOrth(Hons) PhD Neryla Jolly DOBA(T) MA The Australian Orthoptic Journal is peer-reviewed and the official annual scientific journal of Orthoptics Australia. The Australian Orthoptic Journal features original scientific research papers, reviews and perspectives, case studies, invited editorials, letters and book reviews. The Australian Orthoptic Journal covers key areas of orthoptic clinical practice – strabismus, amblyopia, ocular motility and binocular vision anomalies; low vision and rehabilitation; paediatric ophthalmology; neuro-ophthalmology including nystagmus; ophthalmic technology and biometry; and public health agenda. Published by Orthoptics Australia (Publication date: January 2020). Editor’s details: Meri Vukicevic, [email protected]; Discipline of Orthoptics, School of Allied Health, La Trobe University. Linda Santamaria, [email protected]; Department of Surgery, Monash University. -

2019 National Conference Planning Materials

2019 National Conference Planning Materials October 12-14, 2019 San Francisco, CA JW Marriott Union Square Meeting at a Glance JW Marriott Union Square San Francisco, CA Friday, October 11, 2019 4:00 PM – 5:00 PM Executive Committee Salon I 5:00 PM – 7:00 PM Board of Directors Meeting Salon I 7:00 PM New Orthoptist Reception Salon I Saturday, October 12, 2019 7:30 AM – 4:00 PM Registration Prefunction Area 7:30 AM – 9:30 AM Breakfast Prefunction Area 12:00 PM – 1:00 PM Lunch Gallery 8:00 AM – 5:15 PM Instruction Courses Metropolitan ABC 5:30 PM – 6:30 PM Education Committee Meeting Salon I 8:00 PM – 11:00 PM AACO President’s Reception Skyline B/C &Terrace Sunday, October 13, 2019 7:30 AM – 11:00 AM Registration Prefunction Area 7:45 AM – 9:45 AM Breakfast Prefunction Area 8:00 AM – 9:30 AM Scientific Session I Metropolitan ABC 10:00 AM – Noon AACO Business Meeting Metropolitan ABC 3:45 PM – 5:15 PM AAO/AACO/AOC Sunday Moscone Center Symposium Room 3020 No lunch provided this day Monday, October 14, 2019 7:30 AM – 8:30 AM Registration Prefunction Area 7:30 AM – 8:30 AM Breakfast Prefunction Area 8:00 AM – 5:00 PM Exhibits Prefunction Area 8:00 AM – 3:30 PM Scientific Session II Metropolitan ABC 12:00 PM – 1:00 PM Lunch Gallery 12:00 PM – 1:30 PM BVOM Editorial Board Meeting Salon I 1:00 PM – 2:00 PM Scobee Memorial Lecture Metropolitan ABC 2 Table of Contents General Page Meeting at a Glance 2 Table of Contents 3 Program Objectives 4 Saturday Instruction Course Schedule 5 Instruction Course Abstracts 13 President’s Reception 6 Sunday Scientific Session Schedule I 7 Scientific Session I Abstracts 16 AACO Business Meeting 8 AAO/AOC/AACO Sunday Symposium Schedule 9 AAO/AOC/AACO Sunday Symposium Abstract 18 Monday AAP/AACO Joint Symposium Schedule 10 AAP/AACO Joint Symposium Abstracts 19 Scientific Session Schedule II 11 Scientific Session II Abstracts 22 Richard G. -

Orthoptics Curriculum Framework

1 Orthoptics Curriculum Framework Prepared by Dr Anna Horwood on behalf of the Education Committee of the British & Irish Orthoptic Society ©2016 British & Irish Orthoptic Society, Salisbury House, Station Road, Cambridge CB1 2LA Tel: +44 (0)1353 665541 www.orthoptics.org.uk [email protected] Registered Charity number: 326905 Limited company no: 1892427 Registered office: as above 2 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Definition and Roles in Orthoptics ........................................................................................ 4 1.2 Context .................................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Method ................................................................................................................................. 7 1.4 Overview of Scope of Current Orthoptic Practice ................................................................. 8 1.5 Overall Professional Values ................................................................................................... 9 1.6 Entry Requirements .............................................................................................................. 9 1.7 Organisation of this Curriculum ............................................................................................ 9 2 Professional Behaviour, Legal Obligations, Personal Duties and Responsibilities -

A Randomized Clinical Trial of Treatments for Convergence Insufficiency in Children

CLINICAL TRIALS SECTION EDITOR: ROY W. BECK, MD, PhD A Randomized Clinical Trial of Treatments for Convergence Insufficiency in Children Mitchell Scheiman, OD; G. Lynn Mitchell, MAS; Susan Cotter, OD; Jeffrey Cooper, OD, MS; Marjean Kulp, OD, MS; Michael Rouse, OD, MS; Eric Borsting, OD, MS; Richard London, MS, OD; Janice Wensveen, OD, PhD; for the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial (CITT) Study Group Objective: To compare vision therapy/orthoptics, pen- 32.1 to 9.5) but not in the pencil push-ups (mean symp- cil push-ups, and placebo vision therapy/orthoptics as tom score decreased from 29.3 to 25.9) or placebo vision treatments for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in therapy/orthoptics groups (mean symptom score de- children 9 to 18 years of age. creased from 30.7 to 24.2). Only patients in the vision therapy/orthoptics group demonstrated both statistically Methods: In a randomized, multicenter clinical trial, 47 and clinically significant changes in the clinical measures children 9 to 18 years of age with symptomatic conver- of near point of convergence (from 13.7 cm to 4.5 cm; gence insufficiency were randomly assigned to receive PϽ.001) and positive fusional vergence at near (from 12.5 12 weeks of office-based vision therapy/orthoptics, office- prism diopters to 31.8 prism diopters; PϽ.001). based placebo vision therapy/orthoptics, or home-based pencil push-ups therapy. Conclusions: In this pilot study, vision therapy/ orthoptics was more effective than pencil push-ups or pla- Main Outcome Measures: The primary outcome mea- cebo vision therapy/orthoptics in reducing symptoms and sure was the symptom score on the Convergence Insuf- improving signs of convergence insufficiency in chil- ficiency Symptom Survey. -

Name of Condition: Refractive Errors

STANDARD TREATMENT GUIDELINES OPTHALMOLOGY Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Govt. of India 1 Group Head Coordinator of Development Team Dr. Venkatesh Prajna Chief- Dept of Medical Education, Aravind Eye Hospitals, Madurai 2 NAME OF CONDITION: REFRACTIVE ERRORS I. WHEN TO SUSPECT/ RECOGNIZE? a) Introduction: An easily detectable and correctable condition like refractive errors still remains a significant cause of avoidable visual disability in our world. A child, whose refractive error is corrected by a simple pair of spectacles, stands to benefit much more than an operated patient of senile cataract – in terms of years of good vision enjoyed and in terms of overall personality development. In developing countries, like India, it is estimated to be the second largest cause of treatable blindness, next only to cataract. Measurement of the refractive error is just one part of the whole issue. The most important issue however would be to see whether a remedial measure is being made available to the patient in an affordable and accessible manner, so that the disability is corrected. Because of the increasing realization of the enormous need for helping patients with refractive error worldwide, this condition has been considered one of the priorities of the recently launched global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness: VISION 2020 – The Right to Sight. b) Case definition: i. Myopia or Short sightedness or near sightedness ii. Hypermetropia or Long sightedness or Far sightedness iii. Astigmatism These errors happen because of the following factors: a. Abnormality in the size of the eyeball – The length of the eyeball is too long in myopia and too short in hypermetropia. -

Chapter 8: Office-Based Vision Therapy (VT/Orthoptics)

Chapter 8 Office-Based Vision Therapy (VT/Orthoptics) Chapter 8: Office-Based Vision Therapy (VT/Orthoptics)........................................................3 8.1 General Principles and Guidelines for Office-based VT/Orthoptics .........................................3 8.1.1 Therapist Instructions...........................................................................................................3 8.1.2 Subject Instructions..............................................................................................................8 8.1.3 Weekly Office Visits............................................................................................................8 8.1.4 Investigator Instructions.......................................................................................................8 8.1.5 Forms ...................................................................................................................................9 8.1.6 Treatment Compliance.........................................................................................................9 8.1.7 Maintenance Treatment .......................................................................................................9 8.2 Office-based VT/Orthoptics Vision Therapy Equipment Needed.............................................9 8.3 Office-based VT/Orthoptics Vision Therapy Protocol (Flow Sheet) ......................................10 8.4 Office-based VT/Orthoptics Vision Therapy Endpoints (List) ...............................................11 -

Improvement of Therapy for Amblyopia

Improvement of therapy for amblyopia Sjoukje Elizabeth Loudon The research project was initiated by the Department of Ophthalmology, Erasmus MC Uni versity Medical Center Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The work described in this thesis was fi nancially supported by the Health Research and Development Council of the Netherlands (project number 2300.0020). Financial support for the printing of this thesis was received from the Prof.dr. Henkes Stichting, Orthopad, 3M Opticlude, the Rotterdamse Vereniging Blinden belangen and the Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam. ISBN 9789085592682 Copyright © 2007 S.E. Loudon, Rotterdam, the Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the author, or when ap propriate, of the publishers of the publications. Layout and printing: Optima Grafische Communicatie, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Cover design: VOF Vingerling & De Bruyne Improvement of Therapy for Amblyopia Verbeteren van de Behandeling voor Amblyopie Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof.dr. S.W.J. Lamberts en volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op woensdag 21 februari 2007 om 15:45 uur door Sjoukje Elizabeth Loudon geboren te Huddersfield, GrootBrittannië PROMOtieCOMMissie Promotoren Prof.dr. G. van Rij Prof.dr. H.J. Simonsz Overige leden Prof.dr. P.J. van der Maas Prof.dr. J. -

Approach to Esotropia Clearer for You!

This podcast will review an approach to a child presenting with esotropia – the most common type of strabismus. The approach includes history taking, physical examination, specific tests, indication for referral and management of esotropia. This podcast was created by Katia Milovanova, a medical student at the University of Alberta, in collaboration with Dr. Natashka Pollock, a pediatric ophthalmologist at the University of Alberta. 1 Today we will cover the following learning objectives on the topic of esotropia: 1) Define and differentiate the main categories of esotropia. 2) Develop an approach to evaluating a patient with esotropia. 3) Delineate appropriate urgent and non-urgent ophthalmology referrals for esotropia. 4) Discuss general treatment approaches for esotropia. 2 Let’s work through a clinical case as we go, so we can apply the information we are learning. You are a medical student working at an urban family medicine clinic. Tim is a 2.5 year old boy presenting with a new onset esotropia. His mother is worried because she has been noticing his left eye turning in over the last few weeks. Before we begin, we must define ‘strabismus’. Strabismus is simply abnormal alignment of the eyes; one or both eyes may deviate from their primary position. Esotropia is a type of strabismus, in which one or both affected eyes look in towards the nose (colloquially termed ‘cross-eyed’). This is the most common type of strabismus, occurring in 2-4% of the population (which is almost 1 in 20 kids!). 3 It is very important to diagnose and correct esotropia before stereopsis develops around the age of 4.