Systematic Review of SMART Recovery: Outcomes, Process Variables, and Implications for Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Styles of Secular Recovery

White, W. & Nicolaus, M. (2005). Styles of secular recovery. Counselor, 6(4), 58-61. Styles of Secular Recovery William L. White and Martin Nicolaus The last essay in this column noted the growing diversity in religious, spiritual and secular frameworks of recovery and sketched the history of religious approaches to addiction recovery. This essay reviews the history and growing varieties of secular recovery and the implications of such diversity for the addictions professional. A History of Secular Recovery The history of non-religious, non-spiritual approaches to the resolution of alcohol and other drug problems begins with the Washingtonian Revival of the 1840s. The Washingtonians removed preachers and physicians from the temperance lectern in favor of men and women who, in the vernacular of the day, were “reformed” or were “reforming.” The Washingtonians replaced religious admonitions not to drink with 1) public confession of one’s addiction, 2) a signed pledge of abstinence, 3) visits to younger members, 4) economic assistance to new members, 5) experience sharing meetings, 6) outreach to the suffering drunkard, and 7) sober entertainment and fellowship. While many Washingtonians entered the life of their local churches, Washingtonian leaders were charged by their religious critics with committing the sin of humanism--placing their own will above the power of God. Recovery support societies that followed the Washingtonians took on a more religious orientation, but secular recovery groups continued in some of the mid- century moderation societies, ribbon reform clubs and support societies that grew out of early treatment institutions, e.g. the Ollapod Club and the Keeley Leagues. -

Staying Connected Is Important: Virtual Recovery Resources

STAYING CONNECTED IS IMPORTANT: VIRTUAL RECOVERY RESOURCES • Refuge Recovery: Provides online and virtual INTRODUCTION support In an infectious disease outbreak, when social https://www.refugerecovery.org/home distancing and self-quarantine are needed to • Self-Management and Recovery Training limit and control the spread of the disease, (SMART) Recovery: Offers global community continued social connectedness to maintain of mutual-support groups, forums including a recovery is critically important. Virtual chat room and message board resources can and should be used during this https://www.smartrecovery.org/community/ time. Even after a pandemic, virtual support may still exist and still be necessary. • SoberCity: Offers an online support and recovery community This tip sheet describes resources that can be https://www.soberocity.com/ used to virtually support recovery from mental/ substance use disorders as well as other • Sobergrid: Offers an online platform to help resources. anyone get sober and stay sober https://www.sobergrid.com/ • Soberistas: Provides a women-only VIRTUAL RECOVERY PROGRAMS international online recovery community https://soberistas.com/ • Alcoholics Anonymous: Offers online support • Sober Recovery: Provides an online forum for https://aa-intergroup.org/ those in recovery and their friends and family https://www.soberrecovery.com/forums/ • Cocaine Anonymous: Offers online support and services • We Connect Recovery: Provides daily online https://www.ca-online.org/ recovery groups for those with substance use and -

SMART Recovery® History

A Chronology of SMART Recovery® Compiled by Shari Allwood and William White Pre-SMART Recovery Milestones 1975 Jean Kirkpatrick, PhD, founds Women for Sobriety, the first secular alcoholism recovery alternative to Alcoholics Anonymous. 1985 Jack and Lois Trimpey found Rational Recovery (RR). Late 1980s Early 1990s Rational Recovery meetings spread in the US. 1990 Articles in the Boston Globe and the New York Times as well as television coverage on such programs as The Today Show stimulate interest in rational approaches to addiction recovery. The Globe article alone generates more than 400 calls about Rational Recovery. First RR meeting takes place at a hospital: Mount Auburn Hospital, Cambridge, MA, 1990. There are 14 RR groups meeting in the US. 1991 Jack and Lois Trimpey host the first meeting of the informal board of professional advisors to Rational Recovery in February in Dallas, Texas. A number of the individuals who will later start SMART Recovery are in attendance. 1992 Rational Recovery prison meetings start at MCI-Concord (MA) October 6, 1992, led by Barbara Gerstein, RN, and Wally White. Prof. Marc Galanter (NYU) and colleagues conduct a survey study of participants in 30 Rational Recovery groups throughout the US. They conclude that RR engages participants and the likelihood of abstinence increases with the length of participation. 1993 Survey study of Rational Recovery groups by the West End Group, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard Medical School reaches the same conclusions as the 1992 Galanter group study. Rational Recovery training conference is held at Hyatt Harborside Hotel in Boston in conjunction with a scientific meeting featuring James Prochaska and Tom Miller as the main speakers. -

The SMART Recovery 4-Point Program®

CLICK & Donate to SMART Recovery ® Bringing Science and Reason to Self-help with Addictive Behaviors Volume 24, Issue 3 • July 2018 President, Joe Gerstein, M.D., FACP that SMART, LifeRing and surprising since virtually Women For Sobriety everyone in the recovery President’s Letter (WFS) provide recovery community, including support that is as effective scientists, share a common as Alcoholics Anonymous perception of recovery for people with alcohol use support groups. On the one Time to change the conversation disorders. We are thankful hand, there are AA and about SMART and recovery support to Sarah Zemore and her other 12-Step groups, and by Joe Gerstein, M.D., FACP colleagues at the Alcohol on the other, there are By many measures, Research Group for the “alternatives.” SMART is gaining long- conducting this research, sought respect and success. which tracked recovery We are endorsed by the progress among people Inside: world’s leading govern- using each group over a President’s Letter one-year period.1 ment and health Time to change the conversation about authorities focusing on The many media reports SMART and recovery support .........1 addiction. At our current on this research framed the 4-Point Program®.....................1 growth rate, the number of results in a familiar manner People Power weekly meetings will cross – that three “alternative” the 3,000 milestone this support groups are as SMART T-shirts FUNdraiser ...........3 year. Research published effective as AA – often in Call for board candidates ..............3 several -

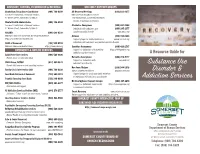

Substance Use Disorder & Addiction Services

ADVOCACY, FUNDING, INFORMATION & REFERRAL SELF-HELP SUPPORT GROUPS Alcoholism/Drug Abuse Coordinator (908) 704-6309 All Recovery Meetings (833) 233-4377 Somerset County Dept. of Human Services RWJ University Hospital Somerset 27 Warren Street, Somerville, NJ 08876 110 Rehill Avenue, Somerville, NJ 08876 Mental Health Administrator (908) 704-6302 Honors all pathways to recovery Somerset County Dept. of Human Services Alcoholics Anonymous (908) 687-8566 27 Warren Street, Somerville, NJ 08876 Individuals with substance use (800) 245-1377 NJCADD (609) 689-0599 (alcohol specific) disorder www.nnjaa.org National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence Al-Anon (973) 744-8686 https://ncaddnj.nationbuilder.com Support groups for family members of www.nj-al-anon.org NAMI of Somerset (732) 940-0991 individuals with substance use (alcohol specific) disorder National Alliance on Mental Illness https://www.nami.org Gamblers Anonymous (800) 426-2537 EMERGENCY & HOTLINE SERVICES Support for individuals with gambling https://800gambler.org addiction and their families A Resource Guide for Adult Protective Services (908) 526-8800 Report abuse of vulnerable Adult Narcotics Anonymous (844) 276-2777 Support for Individuals with www.nanj.org Child Abuse, DCP&P (877) 652-2873 substance use disorder Report child abuse or seek parenting services Substance Use Nar-Anon/Alateen (888) 944-5678 Family Crisis Intervention Unit (908) 704-6330 www.nj-al-anon.org/alateen www.nar-anon.org Food Bank Network of Somerset (732) 560-1813 Support groups for youth and family members Disorder & of individuals with substance use disorder Franklin Township Food Bank (732) 246-0009 NJ Clearinghouse Support Groups (800) 367-6274 Addiction Services HIV/AIDS Hotline (800) 624-2377 Support for individuals experiencing https://www.njgroups.org Information and support a common life situation NJ Addiction Services Hotline (IME) (844) 276-2777 Smart Recovery www.smartrecovery.org 24 hours / 7 days a week for assessment / referral Online support for substance use and gambling addiction. -

Global Support for SMART

Global Support for SMART U.S. Government and Professional Endorsements Understanding Drug Abuse and Addiction: What Science Says Self Help and Drug Addiction Treatment Self-help groups can complement and extend the effects of professional drug addiction treatment. The most prominent groups are those affiliated with Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Narcotics Anonymous (NA), and Cocaine Anonymous (CA) … and SMART Recovery. Most drug addiction treatment programs encourage patients to participate in a self- help group during and after formal treatment.1 SMART’s InsideOut program for correctional facilities was funded by $1 million in NIDA Small Business Innovation Research Grants. SMART offers the court-mandated nonreligious recovery support that meets the best practice standards set by the National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP). Major research has established that the program significantly reduces reconviction rates.2 Understanding the Impact of Alcohol on Human Health and Well-Being Medical Attention | The Patient is Drinking Encouraging patients to go to mutual-support groups such as AA or SMART Recovery is the first-line response in this situation. Although some patients will inform you early on that they have no intention of attending these meetings because of previous negative experiences or a fear of groups, encourage them to try these groups by stressing that a different type of group could be helpful (e.g., going to SMART Recovery instead of AA ….).3 NIH funded CheckUp & Choices (www.smartrecovery.org/checkupandchoices), an evidence-based web app based on SMART’s 4-Point Program that helps people stop drinking, which was developed under the leadership of Reid Hester, Ph.D. -

Maintaining Sobriety How Support Groups Can Help

MAINTAINING SOBRIETY HOW SUPPORT GROUPS CAN HELP Barbara H. Bradford, LICSW March 19, 2014 Overview • What do we know • High cost of substance-related addictive disorders • Role of support groups • Resources What do we know? •More than one-half of American adults have a close family member who has or has had Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) •The federal government estimates that 8.9 percent of full-time workers have drinking problems •Alcohol costs American business an estimated $134 billion in productivity losses, mostly due to missed work •According to SAMHSA, in 2011, 133.4 million people used alcohol & 22.5 million used illicit drugs. What do we know • 22% of men and 14% of women have some type of substance-related addictive disorder (National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2011) • According to the National Center for Health Statistics – there were 38,329 overdose deaths in the US in 2010. 57.7% of those involved pharmaceuticals, 74.3% were unintentional Support group history • Native Americans • Washingtonians • Oxford Groups • Alcoholics Anonymous • Post AA alternatives Alcoholics Anonymous • 1935 “Dr. Bob & Bill W” • Primary features – Admit to having problem with alcohol – Acknowledge role of “Higher Power” – Sharing experience in meeting settings – Peer mentoring (sponsorship) 2.1 million members in 150 countries Strong on line presence with e-groups available Narcotics Anonymous • 1953 NA began in California • AA endorsed NA to make use of AA 12 Steps/traditions • 1970’s time of rapid growth from 20 meetings nationally to 1100 meetings -

AA Alternative Support Groups

AA Alternative Support Groups Secular Organizations for Sobriety (also known as Save Our Selves): Meetings are for people suffering from either alcoholism or drug addiction. SOS encourages the use of science and reason to further develop insight into the nature of one's own drug addiction, rather than spiritual principles or God. They believe that support is critical to helping individuals achieve and maintain sobriety, SOS credits the individual for achieving and maintaining his or her own sobriety, without reliance on any "Higher Power". SOS respects recovery in any form regardless of the path by which it is achieved. It is not opposed to or in competition with any other recovery programs. 4th Floor-Follow Signs The Titus Building Alec Tuesday 7:00 PM Edina 6550 York Ave So 612-405-8000 Mills Church Eric Friday 7:30 PM Minnetonka 13215 Minnetonka Dr 952-222-7697 Health Realization: Health Realization (HR) meetings are for people suffering from either alcoholism or drug addiction. HR focuses on developing the individual's personal capacity to overcome his or her drug or alcohol problem. HR meetings aim to empower such people through teaching conscious awareness of three principles: (1) Mind, (2) Consciousness, and (3) Thought. The goal is for the individual to gain control over their problem by integrating and practicing these three principles in their daily life. Conceptual Counseling 651-221-0334 Monday 5:00 PM St. Paul 287 E. 6th Street - Suite 300 Canvas Health Bruce Monday 7:00 PM Hope House Stillwater 375 East Orleans 651-436-7777 Recovery Church Meg Monday 7:00 PM Steps Room St. -

Chicago Area Additions/Alternatives to 12 Step

CHICAGO AREA ALTERNATIVES (OR ADDITIONS) TO 12 STEP SUPPORT GROUPS MONDAY Refuge Recovery MONDAY 12:00 PM Foundations Recovery Network 225 W Washington St. Suite 550 (2nd fl.), Chicago, IL 60603 (See security desk, sign in and ask for Foundations then take elevator to second floor. Enter from Franklin St. on the west if door on Washington is locked). Contact: [email protected] SMART Recovery MONDAY 12:00 PM Above and Beyond Family Recovery Center 2942 W Lake St.,Chicago, Illinois 60612, USA Contact: [email protected] SMART Recovery MONDAY 1:00 PM Breakthrough Urban Ministries 402 N St Louis Ave., Chicago, IL USA Contact: [email protected] Harm Reduction Group MONDAY 6:00 PM Howard Brown Health Center An affirming, non-judgmental group where clients can explore their substance use, get support for making choices that align with their values, and learn tools to help them reach their goals. Work on specific harm reduction strategies that prioritize safety Learn about withdrawal symptoms Address triggers for substance use Set goals for use for each drug of choice Explore the impact of substance use on relationships, work, school, physical, & mental health Contact: To learn more about this group, please call Sonila Sejdaras, LCSW at 773.572.8353 SMART Recovery Evanston Hospital/Doreen E. Chapman Center - Room 5415 MONDAY 6:00 PM 2650 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60201 USA Contact: [email protected] SMART Recovery MONDAY 6:15 PM Treatment Alternatives for Safe Communities Inc. 225 W Washington St. Suite 200 (2nd fl.), Chicago, IL 60603 Refuge Recovery MONDAY 6:30 PM Gateway Foundation 3828 W. -

Alcohol and Substance Use Disorders

Helpful Resources What to Do if You Know About Alcoholism/Substance Use Disorder Someone with an Alcohol alcoholism.about.com A comprehensive web site that includes information about alcohol or Substance Use Disorder. and drug abuse in teens, college students, and adults; community resources; and self-screening quizzes. Alcoholics AnonymousWorld Service Office (AA) 212.870.3400 | aa.org Many people are affected by the The original 12-step self-help program, with free meetings in nearly drinking or drug use of a family every community. member or friend. Alcohol and Smart Recovery substance use disorders affect every 866.951.5357 | smartrecovery.org A recovery program for individuals who have chosen to abstain, or family member. It is important to are considering abstinence from any type of addictive behaviors remember that you cannot control (substances or activities), by teaching how to change self-defeating thinking, emotions and actions, and to work toward long-term someone else’s behavior. You might satisfaction and quality of life. suggest ways they can get help but Narcotics Anonymous (NA) one of the most frustrating factors 818.773.9999 | na.org in dealing with alcohol or substance A self-help group based on the AA model, NA focuses on other drug problems. use disorders is that they are often accompanied by “denial.” Al-Anon/Alateen Family Groups 888.425.2666 | al-anon.alateen.org A 12-step program designed for those who have been affected by BEHAVIORAL HEALTH There may be little you can do to help someone else’s alcohol or drug problem based on the AA model. -

Global Recognition

SMART RECOVERY SPOTLIGHT GLOBAL RECOGNITION U.S. GOVERNMENT AGENCIES AND PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATIONS NATIONAL INSTITUTE ON DRUG ABUSE group could be helpful (e.g., going to SMART Recovery 3 Understanding Drug Abuse and Addiction: instead of AA …). What Science Says — Self-Help and Drug NIH funded CheckUp & Choices (www.smartrecovery. Addiction Treatment org/checkupandchoices), an evidence-based web Self-help groups can complement and extend the app based on SMART’s 4-Point Program that helps effects of professional drug addiction treatment. people stop drinking, which was developed under The most prominent groups are those affiliated with the leadership of Reid Hester, Ph.D. After NIAAA- Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Narcotics Anonymous (NA), funded research proved its effectiveness, new apps and … SMART Recovery. Most drug addiction treatment were developed for opioids, stimulants, marijuana and programs encourage patients to participate in a self- compulsive gambling. help group during and after formal treatment.1 SMART’s InsideOut program for correctional facilities NIAAA ALCOHOL TREATMENT NAVIGATOR was funded by $1 million in NIDA Small Business Caretaker Support Resources Innovation Research Grants. SMART offers the court- Just as the needs of each person with alcohol use mandated nonreligious recovery support that meets disorder are different, each family’s needs are also the best practice standards set by the National different. Several resources are available to help you Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP). while your loved one is in treatment, and afterwards. Major research has established that the program significantly reduces reconviction rates.2 • Family therapy—often offered as part of a patient’s treatment. If not—or if you need additional or continuing support—you can use the Navigator’s NATIONAL INSTITUTE ON ALCOHOL ABUSE search guides to find a licensed addiction therapist AND ALCOHOLISM who offers family therapy. -

Selected Papers of William L. White

Selected Papers of William L. White www.williamwhitepapers.com Collected papers, interviews, video presentations, photos, and archival documents on the history of addiction treatment and recovery in America. Citation: Kelly, J. & White, W. (2012) Broadening the base of addiction recovery mutual aid. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 7(2-4), 82-101. Posted at www.williamwhitepapers.com Broadening the Base of Addiction Recovery Mutual Aid John F. Kelly, PhD and William L. White, MA Abstract mutual help options. This article presents a concise overview of the Peer-led mutual help organizations origins, size, and state of the science addressing substance use disorder on several of the largest of these (SUD) and related problems have had alternative additional mutual help a long history in the United States. organizations in an attempt to raise The modern epoch of addiction further awareness and help broaden mutual help began in the post- the base of addiction mutual help. prohibition era of the 1930s with the birth of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). Keywords: Mutual help; mutual aid; self Growing from two members to two help; Alcoholics Anonymous; narcotics million members, AA’s reach and anonymous; SMART recovery; Secular influence has drawn much public organization for Sobriety; Women for health attention as well as Sobriety; Moderation Management. increasingly rigorous scientific investigation into its benefits and 1. Introduction mechanisms. In turn, AA’s growth and success has spurred the At first glance, the notion of development of myriad additional individuals with serious, objectively mutual help organizations. These verifiable, cognitive and social impairments alternatives may confer similar being able to facilitate life-saving changes in benefits to those found in studies of similarly impaired individuals may seem a AA, but have received only peripheral little incongruous; from a derisory attention.