An Appraisal of the Classic Forest Succession Paradigm with the Shade Tolerance Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shifts in Forest Composition in the Eastern United States T ⁎ Jonathan A

Forest Ecology and Management 433 (2019) 176–183 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Shifts in forest composition in the eastern United States T ⁎ Jonathan A. Knotta, Johanna M. Despreza, Christopher M. Oswaltb, Songlin Feia, a Purdue University, Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, West Lafayette, IN 47906, United States b USDA Forest Service Southern Research Station, Knoxville, TN 37919, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Forest ecosystems in the United States (U.S.) are facing major challenges such as climate change, exotic species Forest dynamics invasions, and landscape fragmentation. It is widely believed that forest composition in the eastern U.S. is Fire tolerance transitioning from shade-intolerant, fire-tolerant species to shade-tolerant, fire-intolerant species, but most Shade tolerance evidence is anecdotal or localized. No comprehensive studies exist to quantify the shifts in forest composition Mesophication across multiple genera at a regional scale. Here, we examined the genus-level compositional changes in eastern Quercus U.S. forests to: (1) quantify the extent and magnitude of this transition, and (2) assess the influence of shade and Acer fire tolerance traits on abundance change. Genus-level data were compiled from the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) database across 37 states in the eastern U.S. for the last three decades. We analyzed shifts in forest composition with three metrics—stem density, basal area, and importance value—for 10 of the most abundant genera (Acer, Betula, Carya, Fraxinus, Nyssa, Pinus, Populus, Prunus, Quercus, and Ulmus). In addition, we esti- mated density-weighted fire and shade tolerances for each genus using species-level published data, assessed the shifts in spatial patterns of these traits, and analyzed the associations between these traits and county-level abundance changes. -

Tree Growth and Mortality , Reproductive Patterns, and Soil Characteristics in a 27 Year-Old Maple-Basswood Forest Restoration Project

St. Olaf College Local Ecology Research Papers Tree growth and mortality , reproductive patterns, and soil characteristics in a 27 year-old maple-basswood forest restoration project Robby Holmes 2017 © Robby Holmes, 2017 “Tree growth and mortality, reproductive patterns, and soil characteristics in a 27 year-old maple-basswood forest restoration project” by Robby Holmes is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Holmes 1 Tree growth and mortality, reproductive patterns, and soil characteristics in a 27 year-old maple-basswood forest restoration project Robby Holmes Advisor: Dr. Kathleen Shea Biology Department, St. Olaf College Northfield MN, 55057 Fall 2017 Holmes 2 Abstract Forests have been on the decline since the rise of agriculture and urbanization in the last few centuries. The maple-basswood forest, a unique forest type found in southeastern Minnesota, is no exception. Keeping these forests healthy, or restoring them to health, is important in order to preserve high levels of biodiversity to facilitate ecosystem resilience. In this study, we measured over 2000 trees at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, to assess their health and compare tree growth among four sections in two adjacent fields. We also gathered seedling and sapling data as well as soil data to assess the overall health and growth of the forests. The restoration project is dominated by white ash, with black walnut, maples, and oaks being the next most common. Sections one and two had the trees with the largest diameter, lead by red oak, white oak, and basswood, while sections three and four had higher levels of moisture and organic matter. -

How Do Atmospheres Change Over Time? the Greenhouse Effect

Activity #5 How Do Atmospheres Change Over Time? The Greenhouse Effect [Adult] Adapted from: Global Warming & The Greenhouse Effect, Great Explorations in Math and Science (GEMS) Lawrence Hall of Science, 1997, by the Regents of the University of California ISBN: 0-912511-75-3. Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy of SETI Institute. 1. Introduction In this activity, Cadettes will observe how the greenhouse effect can change an atmosphere on Mars or on Earth. They will “Think like a scientist. Be a scientist!” 2. Science Objectives You will: • construct models to test ideas about processes that cannot be directly studied on Earth or Mars; • appreciate that the atmosphere is a large and complex system, so experiments concerning it are difficult to perform; and • use skills you have learned about atmospheric composition and apply that knowledge to new situations. 3. Materials For each group of 4–6 Cadettes. • [2] 2 liter (0.5 gal) clear soda bottles with labels removed and tops cut off. These are the Atmosphere Model Chambers. Advance preparation required (see page 2). • [1] pair of scissors for constructing a set of Atmosphere Model Chambers • [1] black permanent marker for constructing a set of Atmosphere Model Chambers • [2] identical thermometers, one for each chamber; view on Amazon.com: http://tinyurl.com/lkrvzvq • sufficient cardboard to prepare backing for each thermometer • 5–10 cm (about 4 in) of clear tape to attach thermometers to cardboard and to inside of each chamber • [1] piece of plastic wrap approximately 15 cm x 15 cm (6 x 6 in) • [1] rubber band large enough to fit the circumference of chamber and secure plastic wrap • chart of electromagnetic spectrum of light (EMS); print in advance • 250-watt infrared heat lamp (bulb) in a fixture with hood. -

Why Are Evergreen Leaves So Contrary About Shade?

Opinion Why are evergreen leaves so contrary about shade? Christopher H. Lusk1*, Peter B. Reich2*, Rebecca A. Montgomery2, David D. Ackerly3 and Jeannine Cavender-Bares4 1 Department of Biological Science, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia 2 Department of Forest Resources, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN 55108, USA 3 Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 4 Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN 55108, USA Leaf mass per area (LMA) is one of the most widely spectrum (low photosynthetic capacity and respiration measured of all plant functional traits. In deciduous rates, low nitrogen concentrations and long leaf lifespan) forests, there is similarity between plastic and evolution- are not only found in inherently slow-growing species (e.g. ary responses of LMA to light gradients. In evergreens, many evergreen conifers such as Podocarpus and Picea) however, LMA is lower in shaded than sunlit individuals [7,9,10] but are often also expressed within species when of the same species, whereas shade-tolerant evergreens grown in environments unfavorable for rapid growth have higher LMA than light-demanders grown under the [10,11]. For example, leaf lifespan is often longer in shaded same conditions. We suggest that this pattern of ‘coun- individuals than in those grown in brighter light [12,13], ter-gradient variation’ results from some combination of just as it tends to be longer in shade-tolerant species (i) close evolutionary coordination of LMA with leaf adapted to late-successional habitats than in light- lifespan, (ii) selection for different leaf constitutions demanding species, which normally establish under open (relative investment in cell walls versus cell contents) conditions [11,14,15]. -

Invasive Plants in Your Backyard!

Invasive Plants In Your Backyard! A Guide to Their Identification and Control new expanded edition Do you know what plants are growing in your yard? Chances are very good that along with your favorite flowers and shrubs, there are non‐native invasives on your property. Non‐native invasives are aggressive exotic plants introduced intentionally for their ornamental value, or accidentally by hitchhiking with people or products. They thrive in our growing conditions, and with no natural enemies have nothing to check their rapid spread. The environmental costs of invasives are great – they crowd out native vegetation and reduce biological diversity, can change how entire ecosystems function, and pose a threat Invasive Morrow’s honeysuckle (S. Leicht, to endangered species. University of Connecticut, bugwood.org) Several organizations in Connecticut are hard at work preventing the spread of invasives, including the Invasive Plant Council, the Invasive Plant Working Group, and the Invasive Plant Atlas of New England. They maintain an official list of invasive and potentially invasive plants, promote invasives eradication, and have helped establish legislation restricting the sale of invasives. Should I be concerned about invasives on my property? Invasive plants can be a major nuisance right in your own backyard. They can kill your favorite trees, show up in your gardens, and overrun your lawn. And, because it can be costly to remove them, they can even lower the value of your property. What’s more, invasive plants can escape to nearby parks, open spaces and natural areas. What should I do if there are invasives on my property? If you find invasive plants on your property they should be removed before the infestation worsens. -

West Lake Woven Wood Shade Section

West Lake Woven Wood Shade Section Effective April 15, 2014 Save a life: "Install Safety Tension Devices!" Woven Wood Measuring Instructions Measuring Inside Mount (IB) Shades: Measure the exact width (A) and length (B) of the window opening as shown. The factory will deduct ½” overall from the window width for clearance. On all inside mount shades, a small light gap will be visible. Measuring Outside Mount (OB) Shades: Measure the exact width (A) and length (B) of the window opening you wish to cover. The shade should cover the window opening by at least 2” on both the width and length. To cover a window sill, provide a measurement (C) beyond the sill. Outside Mount Inside Mount Measuring Arch Top Valances for Woven Wood Shades: For inside mount shades, measure the exact width and tallest length inside the window opening. For outside mount shades, measure the desired width and tallest length. Make sure to measure the length of outside mount shades at its tallest point. Arch Top woven wood shades must be perfect arches where the length equals ½ the width. For arch top valances, measure dimensions A, X, & Y. For pricing, use the width and tallest length measurement. Make sure to add the arch top shade surcharge. Measuring Angled Shades: It is critical to measure all four sides of the window opening. For inside mount shades, measure the inside of the window opening and for outside mount shades, add the desired overlap. Measure the slope angle with a protractor and provide the angle in degrees. Indicate all measurements on a template to be sent to the factory. -

8040 Introduction to Natural Resources and Ecology Systems

Introduction to Natural Resources and Ecology Systems 8040/36 weeks Table of Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Course Description ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Task Essentials Table .................................................................................................................................... 2 Curriculum Framework ................................................................................................................................. 6 Exploring Leadership Skills through FFA ................................................................................................... 6 Exploring Leadership Opportunities through FFA ....................................................................................... 7 Understanding Natural Resource Management ............................................................................................ 9 Protecting the Environment ........................................................................................................................ 15 Managing Forest Resources ........................................................................................................................ 25 Managing Wildlife Resources .................................................................................................................... -

Natural Resources Inventory

Natural Resources Inventory Columbia Metropolitan Planning Area Review Draft (10-1-10) NATURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY Review Draft (10-1-10) City of Columbia, Missouri October 1, 2010 - Blank - Preface for Review Document The NRI area covers the Metropolitan Planning Area defined by the Columbia Area Transportation Study Organization (CATSO), which is the local metropolitan planning organization. The information contained in the Natural Resources Inventory document has been compiled from a host of public sources. The primary data focus of the NRI has been on land cover and tree canopy, which are the product of the classification work completed by the University of Missouri Geographic Resource Center using 2007 imagery acquired for this project by the City of Columbia. The NRI uses the area’s watersheds as the geographic basis for the data inventory. Landscape features cataloged include slopes, streams, soils, and vegetation. The impacts of regulations that manage the landscape and natural resources have been cataloged; including the characteristics of the built environment and the relationship to undeveloped property. Planning Level of Detail NRI data is designed to support planning and policy level analysis. Not all the geographic data created for the Natural Resources Inventory can be used for accurate parcel level mapping. The goal is to produce seamless datasets with a spatial quality to support parcel level mapping to apply NRI data to identify the individual property impacts. There are limitations to the data that need to be made clear to avoid misinterpretations. Stormwater Buffers: The buffer data used in the NRI are estimates based upon the stream centerlines, not the high water mark specified in City and County stormwater regulations. -

A Shade Tolerance Index for Common Understory Species of Northeastern North America

Ecological Indicators 7 (2007) 195–207 This article is also available online at: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolind A shade tolerance index for common understory species of northeastern North America Lionel Humbert *, Daniel Gagnon, Daniel Kneeshaw, Christian Messier Groupe de Recherche en E´cologie Forestie`re Interuniversitaire (GREFi), De´partement des Sciences Biologiques, Universite´ du Que´bec a` Montre´al, Case Postale 8888, Succursale Centre-Ville, Montre´al, Qc., Canada H3C 3P8 Received 12 June 2005; received in revised form 29 November 2005; accepted 2 December 2005 Abstract Since Baker’s [Baker, F.S., 1949. A revised tolerance table. J. For. 47, 179–181] classic contribution, shade tolerance indices have not been much modified for North American plant species. While many common tree and shrub species are included in the shade tolerance index, much less is known about this characteristic for the abundant and rich understory vascular and nonvascular plant layers. The classification of the shade tolerance is widely used to compare relative growth and survival among plant species under closed canopies and is also fundamental to an understanding of stand development following small and large scale disturbances. Although qualitative, it is frequently used both in research and management implications. Here we provide a significant revision to Baker’s shade tolerance table to include the most common forest understory plant species found in northeastern North America forests. Our index is based on: (1) the compilation of the opinions of five experts, (2) a comparison with Ellenberg’s index from Europe as well as, (3) information from current literature. For most of the 347 plant species investigated, a consistent and robust shade tolerance index, ranging between 1 (very tolerant) and 9 (very intolerant), was found. -

William House Woven Wood Shade Collection

SUGGESTED RETAIL PRICING SEPTEMBER, 2015* WILLIAM HOUSE WOVEN WOOD SHADE COLLECTION *THIS VERSION IS AN ADDENDUM, WHICH CONTAINS SOME PATTERN DISCONTINUATIONS (JAN. 2017) TEXTON.COM 800-442-1540 FAX: 972-276-5104 SEPTEMBER, 2015 MEASURING INSTRUCTIONS MEASURE EACH WINDOW INDIVIDUALLY AS SIZES MAY VARY. RECORD WIDTH FIRST, THEN HEIGHT (LENGTH) TO THE NEAREST 1/8”. MEASURE WIDTH FROM LEFT TO RIGHT, HEIGHT FROM TOP TO BOTTOM USING A METAL TAPE MEASURE. PLEASE DO NOT USE A CLOTH TAPE! INSIDE MOUNT INSIDE MOUNT BLINDS ARE INSTALLED INSIDE THE WINDOW FRAME. 1. MEASURE THE EXACT INSIDE WIDTH OF WINDOW FRAME FROM ONE INSIDE EDGE TO THE OTHER. TAKE THREE MEASURE- MENTS, ONE NEAR THE TOP, ONE IN THE CENTER AND ONE NEAR THE BOTTOM. RECORD THE NARROWEST MEASUREMENT. 2. MEASURE THE EXACT HEIGHT IN THREE PLACES, LEFT, CENTER AND RIGHT FROM TOP EDGE OF OPENING TO TOP OF SILL. RE- CORD THE LONGEST MEASUREMENT FOR WOVEN WOOD SHADES. 3. DO NOT TAKE DEDUCTIONS ON INSIDE MOUNT MEASUREMENTS. THE FACTORY WILL TAKE AN 1/2“ ALLOWANCES FOR 4. OPERATING CLEARANCE. 5. MEASURE THE WINDOW DIAGONALLY IN TWO PLACES. IF THE TWO DIAGONAL MEASUREMENTS ARE NOT THE SAME, WE SUGGEST AN OUTSIDE MOUNT APPLICATION FOR THE BEST SHADE PERFORMANCE AND APPEARANCE. OUTSIDE MOUNT OUTSIDE MOUNT BLINDS ARE INSTALLED OUTSIDE THE WINDOW FRAME, COVERING AN AREA LARGER THAN THE WINDOW ITSELF. 1. MEASURE THE EXACT WIDTH OF AREA TO BE COVERED. BE CERTAIN THE MEASUREMENT OVERLAPS THE WINDOW OPENING BY 2. AT LEAST 1 1/2” ON EACH SIDE TO ENSURE PRIVACY AND LIGHT CONTROL. -

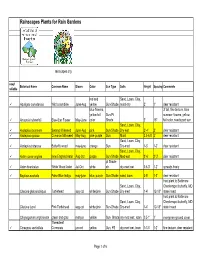

Rainscapes Plants for Rain Gardens

Rainscapes Plants for Rain Gardens rainscapes.org easy/ Botanical Name Common Name Bloom Color Sun Type Soils Height Spacing Comments reliable red and Sand, Loam, Clay, 9 Aquiligea canadensis Wild columbine June-Aug yellow Sun-Shade moist-dry 2' 1' deer resistant blue flowers, 3' tall, fine texture, blue yellow fall Sun-Pt summer flowers, yellow 9 Amsonia hubrechtii Blue-Star Flower May-June color Shade 2' 18" fall color, needs part sun Sand, Loam, Clay, 9 Asclepias incarnata Swamp Milkweed June-Aug pink Sun-Shade Dry-wet 2'-4' 2' deer resistant 9 Asclepias syriaca Common Milkweed May-Aug pale purple Sun Moist 3.5-6.5' 2' deer resistant Sand, Loam, Clay, 9 Asclepias tuberosa Butterfly weed may-june orange Sun Dry-med 1-3' 1-2' deer resistant Sand, Loam, Clay, 9 Aster novae angliae New England Aster Aug-Oct purple Sun-Shade Med-wet 2'-6' 2'-3' deer resistant pt Shade- 9 Aster divaricatus White Wood Aster Jul-Oct white sh dry-med wet 0.5-3' 1-2' spreads freely 9 Baptisia australis False Blue Indigo may-june blue, purple Sun-Shade sand, loam 3-5' 1-2' deer resistant host plant to Baltimore Sand, Loam, Clay, Checkerspot butterfly, MD Chelone glabra/obliqua Turtlehead aug-oct white/pink Sun-Shade Dry-med 1-4' 12-18" state insect host plant to Baltimore Sand, Loam, Clay, Checkerspot butterfly, MD Chelone lyonii Pink Turtlehead aug-oct white/pink Sun-Shade Dry-med 1-4' 12-18" state insect Chrysogonum virginianum green and gold mar-jun yellow Sun- Shade dry-med wet; loam 0.5-1' 1' evergreen ground cover Threadleaf 9 Coreopsis verticillata Coreopsis -

FOREST MANAGEMENT PLAN for the Tobey Hill Town Forest

FOREST MANAGEMENT PLAN for the Tobey Hill Town forest. Weare, New Hampshire Mapped Acres: 53.5 One of the many stone walls found on the Tobey Hill Forest. Prepared for: Prepared by: The town of The Ecosystem Management Company Meadowsend Timberlands, Ltd. Weare, NH PO Box 966 New London, NH 03357 (603) 526-8686 May, 2016 mtlforests.com Management Plan prepared by The Ecosystem Management Co., New London, NH 6/20/2016 PLAN INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE ..................................................................................................................6 PROPERTY LOCATION AND BRIEF DESCRIPTION ..............................................................................................7 GREATER LANDSCAPE PERSPECTIVE .................................................................................................................7 LANDOWNER OBJECTIVES .....................................................................................................................................8 WOODLOT HISTORY ................................................................................................................................................9 FOREST INVENTORY PROCEDURES .....................................................................................................................9 GEOLOGICAL ATTRIBUTES .................................................................................................................................. 12 Physiographic Regions ...................................................................................................................................