Mortgage Shopping Study Overview and Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Rancho to Reservoir

From Rancho to Reservoir: History and Archaeology of the Los Vaqueros Watershed,California edited by Grace H. Ziesing with contributions by Bright Eastman Karana Hattersley-Drayton, M.A. Mary Praetzellis, M.A., SOPA Elaine-Maryse Solari, M.A., Juris Doctor Suzanne B. Stewart, M.A., SOPA Grace H. Ziesing, M.A., SOPA Co-Principal Investigators David A. Fredrickson Adrian Praetzellis Mary Praetzellis prepared for Contra Costa Water District 1231 Concord Avenue Concord, California 94524 prepared by Anthropological Studies Center Sonoma State University Academic Foundation, Inc. 1801 East Cotati Avenue Rohnert Park, California 94928 1997 (reprinted 1999) Note on 1999 reprint: minor corrections have been made to some portions of the text, but they do not constitute a full revision. Cover illustration: Mary Ferrario sits with Evelyn Bonfante and a friend on a Vasco hillside, ca. 1917. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface v CHAPTER 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO LOS VAQUEROS The Changing Countryside 1 What is the Los Vaqueros Project and Why are We Writing this Report? 2 The Los Vaqueros Watershed 4 An Introduction to the Cultural History of the Watershed 7 Los Vaqueros on the Eve of Settlement 8 FOCUSED ESSAYS: Reservoirs and Historic Preservation: The Legal Framework 9 Preserving the Past: Cultural Resources Management at Los Vaqueros 11 A Different Place: The Prehistoric Landscape 14 Early Residents of Los Vaqueros 17 The Ways and Means of History and Archaeology 21 CHAPTER 2. DISPUTED RANGE: RANCHING A MEXICAN LAND GRANT UNDER U.S. RULE, 1844-1880 The Ranchos -

The Relation Between Customer Types in a Real Supermarket Compared to a Virtual Supermarket 1

Volume 9, Number 1 Assembled 2016 (Part 1) April 2016 Editor in Chief Yesha Sivan Tel Aviv University, Israel Issue Editor Sue Gregory School of Education University of New England, Australia Coordinating Editor Tzafnat Shpak The JVWR is an academic journal. As such, it is dedicated to the open exchange of information. For this reason, JVWR is freely available to individuals and institutions. Copies of this journal or articles in this journal may be distributed for research or educational purposes only free of charge and without permission. However, the JVWR does not grant permission for use of any content in advertisements or advertising supplements or in any manner that would imply an endorsement of any product or service. All uses beyond research or educational purposes require the written permission of the JVWR. Authors who publish in the Journal of Virtual Worlds Research will release their articles under the Creative Commons Attribution No Derivative Works 3.0 United States (cc-by-nd) license. The Journal of Virtual Worlds Research is funded by its sponsors and contributions from readers. http://jvwresearch.org The Relation between Customer Types in a Real Supermarket Compared to a Virtual Supermarket 1 Volume 9, Number 1 Assembled 2016 (1) April, 2016 The Relation between Customer Types in a Real Supermarket Compared to a Virtual Supermarket Vassilis-Javed Khan Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands Rebecca Brouwer NHTV Breda University of Applied Sciences, The Netherlands Abstract Virtual environments are becoming more popular for a variety of applications. One application we expect to see in the near future is virtual supermarkets. -

New York State Thoroughbred Breeding and Development Fund Corporation

NEW YORK STATE THOROUGHBRED BREEDING AND DEVELOPMENT FUND CORPORATION Report for the Year 2008 NEW YORK STATE THOROUGHBRED BREEDING AND DEVELOPMENT FUND CORPORATION SARATOGA SPA STATE PARK 19 ROOSEVELT DRIVE-SUITE 250 SARATOGA SPRINGS, NY 12866 Since 1973 PHONE (518) 580-0100 FAX (518) 580-0500 WEB SITE http://www.nybreds.com DIRECTORS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR John D. Sabini, Chairman Martin G. Kinsella and Chairman of the NYS Racing & Wagering Board Patrick Hooker, Commissioner NYS Dept. Of Agriculture and Markets COMPTROLLER John A. Tesiero, Jr., Chairman William D. McCabe, Jr. NYS Racing Commission Harry D. Snyder, Commissioner REGISTRAR NYS Racing Commission Joseph G. McMahon, Member Barbara C. Devine Phillip Trowbridge, Member William B. Wilmot, DVM, Member Howard C. Nolan, Jr., Member WEBSITE & ADVERTISING Edward F. Kelly, Member COORDINATOR James Zito June 2009 To: The Honorable David A. Paterson and Members of the New York State Legislature As I present this annual report for 2008 on behalf of the New York State Thoroughbred Breeding and Development Fund Board of Directors, having just been installed as Chairman in the past month, I wish to reflect on the profound loss the New York racing community experienced in October 2008 with the passing of Lorraine Power Tharp, who so ably served the Fund as its Chairwoman. Her dedication to the Fund was consistent with her lifetime of tireless commitment to a variety of civic and professional organizations here in New York. She will long be remembered not only as a role model for women involved in the practice of law but also as a forceful advocate for the humane treatment of all animals. -

Holiday Week Dance. a Farewell Party

-—- VOLUME XXX. NO. 28. RED BANK, N, J., WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 1, 1908. PAGES 1 TO 8. "PIT" FOLKS FINEB. HOLIDAY WEEK DANCE. A FAREWELL PARTY. The Millers, Joneueii and Others Be- Mrs. 8. 1/. lie. Fabru of little silver fore Jn it UP Jfos/cr. to Winter in Florida. PAVING OF STREETS TO BEGIN ANNUAL CHRISTMAS TREAT AT SOCIETY FOLKS PRESENT IN RED BANK STORES REPORT NEST MARCH. Several residents of "the pit " at Red BKOOHDALE FARM. LAKGE NUMBERS. Last Friday afternoon Mrs. Frank W. AN IMMENSE BUSINESS. Bank were arraigned before Judge Bates of Little Silver gave a farewell The Trolley Company Will Pare Fif- Foster at Freehold last week. They 8. Thompson, Proprietor of SI any fluentti from Out of Town— party to her mother, Mrs. S. L. de The Holiday Helling the Largest in teen Feet on Front Street and were all charged with keeping a disord- the. Farm, Given a Hociabte to Mia The Vance, Which Wan Arranged Fabry, who will spend the winter in- the History of the Town—AlmoeS Mlohteeti Feet on Broad Street- litnployees and Their Faintllen— ay Four Red itanlc I'otiug Men, livery utitrf Showed a Big Xtu Work to be Completed by June Int. erly house. Two of them were Robert About ISO Persons Present. Proven a Large Success. Florida. An enjoyable afternoon was crease Over Farmer Wears. and Emma Jones. The man retracted The commisBioners and W. P. Hogan spent playing games and in general so- his former plea of not guilty and the Louis S. Thompson, proprietor of , A select dance, attended by nearly The holiday trade in the stores of held a meeting on Monday morning and ciability. -

Download Going Bad Meek Drake Mp4 Drake X Meek Mill Going Bad Type Melody

download going bad meek drake mp4 Drake X Meek Mill Going Bad Type Melody. Description : Comment below what you made with this loop ! To contact me either message me here or via Instagram - This loop works for the style of Lil Baby, Gunna, Cubeatz, Young thug, Trippie Redd, Lil Uzi Vert, Meek Mill, Drake. This 143 bpm trap piano loop has been kindly uploaded by carsonbeats. If you use this loop please leave your comments. Read the loops section of the help area and our terms and conditions for more information on copyright and how you can use loops. Any questions on using these files contact the user who uploaded them. Please contact us to report any files that you feel may be in breach of copyright or our upload guidelines. Drake x Meek Mill Going Bad Type Melody by carsonbeats has received 4 comments since it was uploaded. If you have used this loop leave some feedback or say thanks and post a link to the track you made. Apart from being the right thing to do it also encourages artists to upload more loops. KINGVIDEOS. KingVideos is committed to being the #1 source for Music Videos DVDs on the planet. KingVideos offers an insane selection of music videos mixtapes featuring today's hottest artist & videos. Get ultra-high resolution DVDs and HD Digital Downloads (mp4-video format) that will play perfectly in your car or on any media device. We guarantee no site offers higher quality music videos. All HD Digital Downloads are available immediately. All DVD orders usually ship within 1 business day. -

X Minutes of the City of Yonkers Zoning Board of Appeals September 23, 2008 - 6:15 P.M

Page 1 STATE OF NEW YORK CITY OF YONKERS -----------------------------------------------X Minutes of The City of Yonkers Zoning Board of Appeals September 23, 2008 - 6:15 p.m. at City Hall 87 Nepperhan Avenue Yonkers, New York 10701-3892 -----------------------------------------------X B E F O R E: JOSEPH CIANCIULLI, Chairperson JAMES BLANCHARD, Member DIANE PEARSON, Member NANCY LITTLE, Member LEVAR BURKE, Member SAMUEL SINGH, Member ANTHONY LANDI, Member LEE ELLMAN, Planning ALAIN NATCHEV, Assistant Corporation Counsel DOUGLASS REPORTING COMPANY 50 Main Street White Plains, New York 10606 (914) 946-1059 Page 2 1 Proceedings 2 MR. CIANCIULLI: Ladies and 3 gentlemen, can I have your attention, 4 please. You want to take a seat, 5 please? Thank you. 6 The September 23rd, 2008 Zoning 7 Board of Appeals public hearing is now 8 in session. Will the members introduce 9 themselves. Ms. Pearson. 10 MS. PEARSON: Diane Pearson. 11 MR. LANDI: Anthony Landi. 12 MS. LITTLE: Nancy Little. 13 MR. SINGH: Samuel Singh. 14 MR. BLANCHARD: James Blanchard. 15 MR. CIANCIULLI: I am Joseph 16 Cianciulli. I am Chairman of the Board 17 and I think Mr. Burke is going to be 18 late tonight. Would everybody please 19 stand for the pledge of allegiance by 20 Bill Schneider. 21 (Pledge of allegiance). 22 MR. CIANCIULLI: Please be seated. 23 This room is a tough room. We don't 24 have any microphones. We don't have 25 anything, no air conditioning, but we Page 3 1 Proceedings 2 got heat, yes, we do, but anyway, we 3 don't allow any talking in chambers so 4 I am going ask you to go outside if you 5 want to talk. -

Racing Flow-TM FLOW + BIAS REPORT: 2008

Racing Flow-TM FLOW + BIAS REPORT: 2008 CIRCUIT=1-NYRA date=12/31/08 track=Dot race surface dist winner BL12 BIAS RACEFLOW 1 DIRT 6.00 Lights Off Annie 0.0 59 8 2 DIRT 6.00 Apple 0.0 59 -69 3 DIRT 6.00 Mr Madison 13.2 59 -39 4 DIRT 8.32 Cat Three Approach 29.7 59 97 5 DIRT 6.00 Great Emperor 8.1 59 39 6 DIRT 6.00 Personal Good 11.2 59 -58 7 DIRT 6.00 Serious Fever 0.0 59 35 8 DIRT 13.00 Delosvientos 0.0 59 33 9 DIRT 6.00 Mrs Holden 0.0 59 23 CIRCUIT=1-NYRA date=12/28/08 track=Dot race surface dist winner BL12 BIAS RACEFLOW 1 DIRT 8.50 Curvature 11.7 206 -85 2 DIRT 6.00 Coaltown Legend 20.5 206 264 3 DIRT 6.00 Pu Dew 7.2 206 151 4 DIRT 6.00 Mr. Fantasy 0.5 206 180 5 DIRT 8.50 Northern Buster 6.0 206 153 6 DIRT 6.00 Mia's First 4.5 206 96 7 DIRT 8.50 Eltish Star 11.2 206 137 8 DIRT 8.50 R Clear Victory 3.5 206 -207 9 DIRT 6.00 Undocumented 19.5 206 106 CIRCUIT=1-NYRA date=12/27/08 track=Dot race surface dist winner BL12 BIAS RACEFLOW 1 DIRT 6.00 Sunday Elegance 2.0 39 19 2 DIRT 8.32 Tee With the Tiger 12.7 39 71 3 DIRT 6.00 Z Day 0.0 39 -8 4 DIRT 6.00 Zip of Fools 0.0 39 67 5 DIRT 6.00 Confirmondi 2.5 39 183 6 DIRT 8.32 Rodeo Hand 13.7 39 49 7 DIRT 6.00 January Gent 3.5 39 52 8 DIRT 6.00 Fabulous Strike 5.0 39 32 9 DIRT 8.32 Manteca 7.5 39 44 CIRCUIT=1-NYRA date=12/26/08 track=Dot race surface dist winner BL12 BIAS RACEFLOW 1 DIRT 6.00 Gimmearoutine 2.2 -14 -78 2 DIRT 8.00 Father Tim 0.0 -14 1 3 DIRT 8.00 Tulipmania 8.0 -14 -90 4 DIRT 6.00 Living Out a Dream 8.0 -14 41 5 DIRT 5.50 Kamboo Man 0.0 -14 -110 6 DIRT 6.00 Momwnt Sensor 2.5 -14 -

Promo Only Country Radiodate

URBAN RADIO ARTIST 05 01 17 OPEN this on your computer. Place your cursor in the “X” Colum. Use the down arrow to move down the cell and place an “X” infront of the song you want played. Forward the file by attachment to [email protected] or F 713-661-2218 X TRK TITLE ARTIST DATE LENGTH BPM STYLE 16 Chill Bill $tone, Rob f./ J. Davi$ & Spooks 11/1/2016 2:58 54 Hip-Hop 16 Chill Bill $tone, Rob f./ J. Davi$ & Spooks 11/1/2016 2:58 54 Hip-Hop JuJu On That Beat (TZ 7 Anthem) & zayion mccall Zay Hilfigerrr 12/1/2016 2:23 80 Hip-Hop JuJu On That Beat (TZ 7 Anthem) & zayion mccall Zay Hilfigerrr 12/1/2016 2:23 80 Hip-Hop 15 Im The Man (Fifty) 50 Cent f./ Sonny Digital 4/1/2016 3:53 98 Hip-Hop 15 Im The Man (Fifty) 50 Cent f./ Sonny Digital 4/1/2016 3:53 98 Hip-Hop 15 Used 2 2 Chainz 13-Nov 3:45 89 Urban 7 Watch Out 2 Chainz 11/1/2015 3:23 65 Hip-Hop 13 I\'m Different 2 Chainz 13-Jan 3:25 97 Hip Hop 12 Riot 2 Chainz 12-May 2:44 65 Hip Hop 22 Gotta Lotta 2 Chainz & Lil Wayne 6/1/2016 3:22 82 Hip-Hop 22 Gotta Lotta 2 Chainz & Lil Wayne 6/1/2016 3:22 82 Hip-Hop 15 Big Amount 2 Chainz f./ Drake 10/1/2016 3:06 67 Hip-Hop 15 Big Amount 2 Chainz f./ Drake 10/1/2016 3:06 67 Hip-Hop 9 Good Drank 2 Chainz f./ Gucci Mane & Quavo 3/1/2017 3:41 66 Hip-Hop 3 No Lie 2 Chainz f./Drake 12-Jul 3:56 65 Urban 9 Netflix 2 Chainz f./Fergie 13-Oct 3:53 62 Rhythm/Urban 2 Feds Watching 2 Chainz f./Pharrell 13-Aug 4:05 70 Rhythm/Urban 15 Milly Rock 2 Milly 2/1/2016 3:39 70 Hip-Hop 15 Milly Rock 2 Milly 2/1/2016 3:39 70 Hip-Hop 10 Milly Rock 2 Milly f./ A$AP -

Övningshandledning För Fältarbetsvecka På Österlen, NGE501

Åkerman 2019 Excursion guide NW Skåne, NGEA 01, 2019 PART 1. Introduction by Associate Prof. Jonas Åkerman 1 Åkerman 2019 Cover photo; The NW exposed coastline at Josefinelust with coarse beach boulders (Sw. “malar”), gneiss is the mother rock intersected by various intrusive rocks in dykes. (Photo J. Åkerman) 2 Åkerman 2019 Innehåll INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 EXCURSION TO NW SKÅNE .................................................................................................................................. 6 Endo - and exogenic processes during the geological history ............................................................................... 12 The excursion area .................................................................................................................................................... 13 The area to the North and Northwest of Lund ...................................................................................................... 13 Geomorphology and endogenic and exogenic processes in central and NW Skåne ............................................. 14 Exogenic processes during the geological development ................................................................................... 14 Mesozoic weathering and land forms ................................................................................................................ 16 The horsts of Skåne .............................................................................................................................................. -

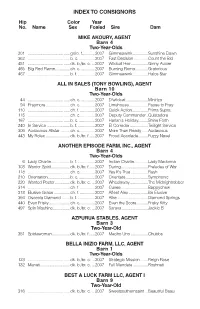

TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No

INDEX TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No. Name Sex Foaled Sire Dam MIKE AKOURY, AGENT Barn 4 Two-Year-Olds 201 ................................. ......gr/ro. f............2007 Gimmeawink ..............Sunshine Dawn 362 ................................. ......b. c................2007 Fast Decision .............Count the Bid 451 ................................. ......dk. b./br. c. ...2007 Wildcat Heir................Ginny Auxier 465 Big Red Flame..............ch. c. .............2007 Burning Roma............Gratorious 467 ................................. ......b. f. ................2007 Gimmeawink ..............Halos Star ALL IN SALES (TONY BOWLING), AGENT Barn 10 Two-Year-Olds 44 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2007 D'wildcat.....................Miniriza 94 Praymore.......................ch. c. .............2007 Limehouse..................Pause to Pray 110 ................................. ......ch. f. ..............2007 Quick Action...............Prima Supra 115 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2007 Deputy Commander..Quistadora 167 ................................. ......b. c................2007 Harlan's Holiday.........Shine Forth 240 In Service ......................b. f. ................2007 El Corredor.................Twilight Service 306 Audacious Allstar .........ch. c. .............2007 More Than Ready......Audacious 443 My Rolex .......................dk. b./br. f......2007 Proud Accolade.........Fuzzy Navel ANOTHER EPISODE FARM, INC., AGENT Barn 4 Two-Year-Olds 6 Lady Charlie..................b. -

Event Transcript

REFINITIV STREETEVENTS EDITED TRANSCRIPT Q1 2021 Yunji Inc Earnings Call EVENT DATE/TIME: MAY 27, 2021 / 11:00AM GMT REFINITIV STREETEVENTS | www.refinitiv.com | Contact Us 1 ©2021 Refinitiv. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Refinitiv content, including by framing or similar means, is prohibited without the prior written consent of Refinitiv. 'Refinitiv' and the Refinitiv logo are registered trademarks of Refinitiv and its affiliated companies. MAY 27, 2021 / 11:00AM GMT, Q1 2021 Yunji Inc Earnings Call CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Chengqi Zhang Yunji Inc. - VP of Finance Kaye Liu Yunji Inc. - IR Director Shanglue Xiao Yunji Inc. - Founder, Chairman & CEO CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS Ethan Yu First Trust Group PRESENTATION Operator Good morning and good evening, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you, and welcome to Yunji's First Quarter 2021 Earnings Conference Call. With us today are Mr. Shanglue Xiao, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer; Chengqi Zhang, Vice President of Finance; and Ms. Kaye Liu, Investor Relations Director of the company. Now I would like to hand the conference over to your first speaker today, Ms. Kaye Liu, IRD of Yunji. Please go ahead, ma'am. Kaye Liu Yunji Inc. - IR Director Hello, everyone. Welcome to our first quarter 2021 earnings call. Before we start, please note that this call will contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 that are based on our current expectations and current market operating conditions and relate to events that involve known or unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors of Yunji and its industry. These forward-looking statements can be identified by terminology such as will, expect, anticipate, continue or other similar expressions. -

Dear Comittee.Pages

February 16, 2015 Re: Bills to raise the minimum wage (HB 1355), establish minimum standards for paid sick and safe time (HB 1356), and protect employees from retaliation (HB 1354) Dear Members of the House Appropriations Committee: Thank you for providing the opportunity for working people to speak before your committee about why raising the minimum wage and creating a minimum standard for paid sick days is good for workers, good for communities, and good for the whole economy. The testimony you hear today will offer some insight into what it’s like to try and support yourself on a poverty-wage job. But a few minutes in a hearing room isn't enough to represent the experiences of the more than half-million people in our state who are paid poverty wages of less than $15/hour, or the million workers who don’t have paid sick days. That’s why we asked people across the state to answer a simple question: What's one thing you’ve done to make ends meet that state politicians don't know anything about? Here is a sampling some of the stories we received in just a few days: Lynn, Poulsbo: "When my kids were younger, I remember going into the basement and garage to find unused outdoor light bulbs, taking them back to a hardware store, using the cash to buy food. $30. Now I'm on EBT.” GG, Orting: “I’m unable to buy new tires that are really needed now. I’ve cut down on every basic need, no going out.