To What Extent Has Canada Affirmed Collective Rights?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Alberta

670 ALBERTA v. CUNNINGHAM [2011] 2 S.C.R. Her Majesty The Queen in Right of Alberta Sa Majesté la Reine du chef de l’Alberta (Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and (Ministre des Affaires autochtones et Northern Development) and Registrar, Metis Développement du Nord) et Registraire, Metis Settlements Land Registry Appellants Settlements Land Registry Appelants v. c. Barbara Cunningham, John Kenneth Barbara Cunningham, John Kenneth Cunningham, Lawrent (Lawrence) Cunningham, Lawrent (Lawrence) Cunningham, Ralph Cunningham, Lynn Cunningham, Ralph Cunningham, Lynn Noskey, Gordon Cunningham, Roger Noskey, Gordon Cunningham, Roger Cunningham, Ray Stuart and Peavine Métis Cunningham, Ray Stuart et Peavine Métis Settlement Respondents Settlement Intimés and et Attorney General of Ontario, Attorney Procureur général de l’Ontario, procureur General of Quebec, Attorney General for général du Québec, procureur général de la Saskatchewan, East Prairie Métis Settlement, Saskatchewan, East Prairie Métis Settlement, Elizabeth Métis Settlement, Métis Nation Elizabeth Métis Settlement, Métis Nation of of Alberta, Métis National Council, Métis Alberta, Ralliement national des Métis, Métis Settlements General Council, Aboriginal Settlements General Council, Aboriginal Legal Services of Toronto Inc., Women’s Legal Services of Toronto Inc., Fonds d’action Legal Education and Action Fund, Canadian et d’éducation juridiques pour les femmes, Association for Community Living, Gift Association canadienne pour l’intégration Lake Métis Settlement and Native Women’s communautaire, Gift Lake Métis Settlement Association of Canada Interveners et Association des femmes autochtones du Canada Intervenants Indexed as: Alberta (Aboriginal Affairs and Répertorié : Alberta (Affaires autochtones Northern Development) v. Cunningham et Développement du Nord) c. Cunningham 2011 SCC 37 2011 CSC 37 File No.: 33340. -

Constitution of Alberta Amendment Act, 1990

Province of Alberta CONSTITUTION OF ALBERTA AMENDMENT ACT, 1990 Revised Statutes of Alberta 2000 Chapter C-24 Current as of January 1, 2002 © Published by Alberta Queen’s Printer Alberta Queen’s Printer 7th Floor, Park Plaza 10611 - 98 Avenue Edmonton, AB T5K 2P7 Phone: 780-427-4952 Fax: 780-452-0668 E-mail: [email protected] Shop on-line at www.qp.alberta.ca Copyright and Permission Statement Alberta Queen's Printer holds copyright on behalf of the Government of Alberta in right of Her Majesty the Queen for all Government of Alberta legislation. Alberta Queen's Printer permits any person to reproduce Alberta’s statutes and regulations without seeking permission and without charge, provided due diligence is exercised to ensure the accuracy of the materials produced, and Crown copyright is acknowledged in the following format: © Alberta Queen's Printer, 20__.* *The year of first publication of the legal materials is to be completed. Note All persons making use of this document are reminded that it has no legislative sanction. The official Statutes and Regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpreting and applying the law. CONSTITUTION OF ALBERTA AMENDMENT ACT, 1990 Chapter C-24 Table of Contents 1 Constitution amended 2 Definition 3 Expropriation 4 Exemption from seizure 5 Restriction on Legislative Assembly 6 Application of laws 7 Power to affect Act 8 Repeal WHEREAS the Metis were present when the Province of Alberta was established and they and the land set aside for their use form a unique part of the history and culture -

Making Federalism Through

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-12-19 Making Federalism through Law: Regulating Socio-economic Challenges of Energy Development, a Case Study of Alberta’s Oil sands and the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo Thompson, Chidinma Bernadine Thompson, C. B. (2013). Making Federalism through Law: Regulating Socio-economic Challenges of Energy Development, a Case Study of Alberta’s Oil sands and the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26816 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1216 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Making Federalism through Law: Regulating Socio-economic Challenges of Energy Development, a Case Study of Alberta’s Oil sands and the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo by Chidinma Bernadine Thompson A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Faculty of Law Calgary, Alberta December 2013 © Chidinma Bernadine Thompson 2013 DEDICATION TO MY ROCK, SWORD AND SHIELD, MY BEST FRIEND, JESUS CHRIST; THIS IS ONLY POSSIBLE BECAUSE YOU SAID SO, THAT THE WORLD MAY KNOW THAT YOU ARE TRUE AND THAT WITH YOU ALL THINGS ARE POSSIBLE. -

PUBLICATIONS SPP Research Paper

PUBLICATIONS SPP Research Paper Volume 11:25 September 2018 WHY ALBERTA NEEDS A FISCAL CONSTITUTION F.L. (Ted) Morton SUMMARY Alberta will enter the third decade of the 21st century with an accumulated public debt of over $70 billion and the highest per capita deficit of any Canadian province. This is a far cry from 2005, when then-premier Ralph Klein announced that Alberta was “debt free”; made the first deposit of energy revenues in the Heritage Fund in 20 years; and enacted a balanced budget law (BBL) that was intended to prevent future governments from ever running deficits again. This statutory BBL lasted only as long as oil prices remained above $100/barrel. It was amended in 2009 to allow “temporary deficits”. Since then, four premiers from two parties chose to run large budget deficits to fund large spending increases to win their next elections. Alberta’s experience proves that statutory rules are not sufficient to protect a positive fiscal legacy. Alberta’s balanced budget law, flat tax rates and protections of the Heritage Fund were all removed by simple majority votes in the Alberta legislature. Any meaningful re-instatement of these policies will require that they be put beyond the reach of future governments of whatever party – that is, that they be constitutionally entrenched. The next Alberta government could address this problem by adapting a form of the BBLs found in most state constitutions in the United States. Under Sections 43 of the Constitution Act, 1982, Alberta could proceed bilaterally by negotiating with the Federal government to “patriate” the Alberta Act from Ottawa to Alberta; and to include in this act a new super-majority amending formula such as a two-thirds approval vote in the Legislature and/or approval by way of referendum. -

SS9 Chapter 4 PP

Collective Rights Chapter 4 Collective Rights ► To what extent has Canada affirmed collective rights? § What laws recognize the collective rights of First Nations peoples? § What collective rights do official language groups have under the Charter? § What laws recognize the collective rights of the Métis? VocaBulary ► Affirm ► Ethnocentrism ► Collective identity ► Indian Act ► Collective rights ► Anglophone ► First Nations ► Francophone ► Official language ► Indian community ► Sovereignty ► Official language ► Annuity minority ► Reserve ► PuBlicly funded ► Entrenching ► Inherent rights ► Patriate ► Scrip ► Assimilate ► Autonomy What are Collective Rights? ►Rights held By groups in Canadian society recognized and protected in the constitution ►Different from individual rights and freedoms found in the Charters Who Holds Collective Rights ►First Nations, Metis, and Inuit ►Francophones and Anglophones Why Do Only Some People Have Collective Rights? ►Recognize the founding people of Canada. ►Come from the roots of ABoriginal, Francophone, and Anglophones in the land and history of Canada. What are the NumBered Treaties? ►Roots in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 § Recognized First Nation’s rights to land and estaBlished framework to make treaties What are the NumBered Treaties? ►Agreements between the Queen and First Nations ►First Nations agreed to share land and resources in peace § Government agreed to cover education, reserves, and annuities What are the NumBered Treaties? ►For First Nations, treaties are sacred, nation-to-nation agreements -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 27th Legislature Fourth Session Alberta Hansard Monday afternoon, December 5, 2011 Issue 45 The Honourable Kenneth R. Kowalski, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature Fourth Session Kowalski, Hon. Ken, Barrhead-Morinville-Westlock, Speaker Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort, Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Zwozdesky, Gene, Edmonton-Mill Creek, Deputy Chair of Committees Ady, Hon. Cindy, Calgary-Shaw (PC) Kang, Darshan S., Calgary-McCall (AL), Allred, Ken, St. Albert (PC) Official Opposition Whip Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Klimchuk, Hon. Heather, Edmonton-Glenora (PC) Anderson, Rob, Airdrie-Chestermere (W), Knight, Hon. Mel, Grande Prairie-Smoky (PC) Wildrose Opposition House Leader Leskiw, Genia, Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) Benito, Carl, Edmonton-Mill Woods (PC) Liepert, Hon. Ron, Calgary-West (PC) Berger, Evan, Livingstone-Macleod (PC) Lindsay, Fred, Stony Plain (PC) Bhardwaj, Naresh, Edmonton-Ellerslie (PC) Lukaszuk, Hon. Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC) Bhullar, Manmeet Singh, Calgary-Montrose (PC) Deputy Government House Leader Blackett, Hon. Lindsay, Calgary-North West (PC) Lund, Ty, Rocky Mountain House (PC) Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL), MacDonald, Hugh, Edmonton-Gold Bar (AL) Official Opposition House Leader Marz, Richard, Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (PC) Boutilier, Guy C., Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (W) Mason, Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (ND), Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Nose Hill (PC) Leader of the ND Opposition Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) McFarland, Barry, Little Bow (PC) Campbell, Robin, West Yellowhead (PC), McQueen, Diana, Drayton Valley-Calmar (PC) Government Whip Mitzel, Len, Cypress-Medicine Hat (PC) Chase, Harry B., Calgary-Varsity (AL) Morton, F.L., Foothills-Rocky View (PC) Dallas, Hon. -

Tax and Expenditure Limitations the Next Step in Fiscal Discipline

Tax and Expenditure Limitations The Next Step in Fiscal Discipline Jason Clemens, Todd Fox, Amela Karabegović, Sylvia LeRoy, and Niels Veldhuis Contents About the authors / 2 Acknowledgments / 3 Foreword by Patrick Basham / 4 Executive summary / 5 Introduction / 7 Balanced budgets and tax and expenditure limitations—clarifying the difference / 8 American experiments with tax and expenditure limitations / 16 Canada’s constitutional framework—options for TELs in Canada / 22 Conclusion / 26 Appendix A: Provincial laws prescribing balanced budgets and TELs / 27 Appendix B: State laws prescribing TELs in the United States / 31 References / 33 The Fraser Institute / 1 Tax and Expenditure Limitations About the Authors JASON CLEMENS is the Director of Fiscal Studies at The Fraser Institute. He has an Honours Bachelors Degree of Commerce and a Masters’ Degree in Business Administration from the University of Windsor as well as a Post-Baccalaureate Degree in Economics from Simon Fraser University. His publications and co-publications for The Fraser Institute include Canada’s All Government Debt (1996), Bank Mergers (1998), The 20% Foreign Property Rule (1999), Returning British Columbia to Prosper- ity (2001), Flat Tax: Issues and Principles (2001), The Corporate Capital Tax: Canada’s Most Damaging Tax (2002), Saskatchewan Prosperity: Taking the Next Step (2002), and Ontario Prosperity (2003). His articles have appeared in such newspapers as The Wall Street Journal, The National Post, The Globe & Mail, The Vancouver Sun, The Calgary Herald, and The Montreal Gazette. He has been a guest on numerous radio and television programs across the country and has appeared before committees of both the House of Commons and the Senate as an expert witness. -

The Right to Water – NACOSAR and Indigenous Women

THE RIGHT TO WATER NACOSAR AND INDIGENOUS WOMEN 2010 Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................3 PART I ‐ INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT ...................................................................................................5 Genesis of the Human Right to Water – References to Indigenous Peoples .............................................5 The World Water Forums....................................................................................................................... 14 PART II ‐ Aboriginal Rights to Water under Canadian Law and Policy ................................................... 18 First Nations Peoples .............................................................................................................................. 19 Inuit and Métis Peoples .......................................................................................................................... 27 Co‐Management Regimes – Inuit, .......................................................................................................... 30 Métis and First Nation ............................................................................................................................ 30 Duty to Consult with Indigenous Peoples .............................................................................................. 33 Use of Rights for New Purposes ........................................................................................................... -

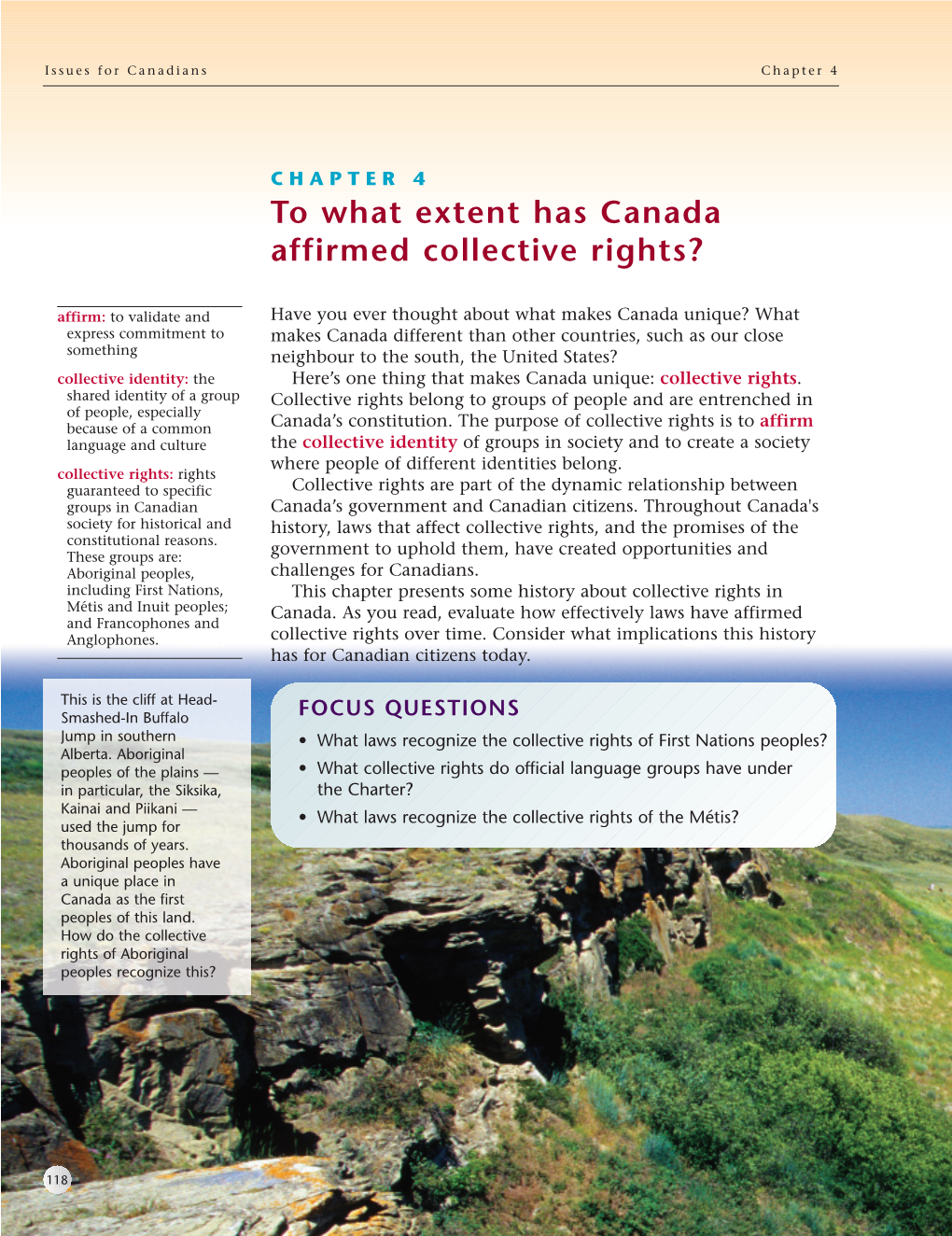

To What Extent Has Canada Affirmed Collective Rights?

Issues for Canadians Chapter 4 CHAPTER 4 To what extent has Canada affirmed collective rights? affirm: to validate and Have you ever thought about what makes Canada unique? What express commitment to makes Canada different than other countries, such as our close something neighbour to the south, the United States? collective identity: the Here’s one thing that makes Canada unique: collective rights. shared identity of a group Collective rights belong to groups of people and are entrenched in of people, especially because of a common Canada’s constitution. The purpose of collective rights is to affirm language and culture the collective identity of groups in society and to create a society where people of different identities belong. collective rights: rights guaranteed to specific Collective rights are part of the dynamic relationship between groups in Canadian Canada’s government and Canadian citizens. Throughout Canada's society for historical and history, laws that affect collective rights, and the promises of the constitutional reasons. These groups are: government to uphold them, have created opportunities and Aboriginal peoples, challenges for Canadians. including First Nations, This chapter presents some history about collective rights in Métis and Inuit peoples; Canada. As you read, evaluate how effectively laws have affirmed and Francophones and Anglophones. collective rights over time. Consider what implications this history has for Canadian citizens today. This is the cliff at Head- Smashed-In Buffalo FOCUS QUESTIONS Jump in southern • What laws recognize the collective rights of First Nations peoples? Alberta. Aboriginal peoples of the plains — • What collective rights do official language groups have under in particular, the Siksika, the Charter? Kainai and Pekuni — • What laws recognize the collective rights of the Métis? used the jump for thousands of years. -

Peavine Metis Settlement V. Alberta (2001), (Sub Nom

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 1 2011 CarswellAlta 1210, 2011 SCC 37, [2011] A.W.L.D. 3138, [2011] A.W.L.D. 3137, [2011] A.W.L.D. 3136, [2011] A.W.L.D. 3119, [2011] A.W.L.D. 3118, [2011] A.W.L.D. 3117, [2011] 3 C.N.L.R. 36 2011 CarswellAlta 1210, 2011 SCC 37, [2011] A.W.L.D. 3138, [2011] A.W.L.D. 3137, [2011] A.W.L.D. 3136, [2011] A.W.L.D. 3119, [2011] A.W.L.D. 3118, [2011] A.W.L.D. 3117, [2011] 3 C.N.L.R. 36 Peavine Métis Settlement v. Alberta (Minister of Aboriginal Affairs & Northern Development) Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Alberta (Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development) and Re- gistrar, Metis Settlements Land Registry, Appellants and Barbara Cunningham, John Kenneth Cunningham, Lawrent (Lawrence) Cunningham, Ralph Cunningham, Lynn Noskey, Gordon Cunningham, Roger Cunningham, Ray Stuart and Peavine Métis Settlement, Respondents and Attorney General of Ontario, Attorney General of Quebec, Attorney General for Saskatchewan, East Prairie Métis Settlement, Elizabeth Métis Settlement, Métis Nation of Alberta, Métis National Council, Métis Settlements General Council, Aboriginal Legal Services of Toronto Inc., Women's Legal Education and Action Fund, Canadian Association for Community Living, Gift Lake Métis Settlement and Native Women's Association of Canada, Interveners Supreme Court of Canada Abella J., Binnie J., Charron J., Cromwell J., Deschamps J., Fish J., LeBel J., McLachlin C.J.C., Rothstein J. Heard: December 16, 2010 Judgment: July 21, 2011 Docket: 33340 © Thomson Reuters Canada Limited or its Licensors (excluding individual court documents). -

In Search of a Quebec Constitution

In Search of a Quebec Constitution Nelson Wiseman* This paper ponders the quest for a new Quebec Constitution. It makes some comparisons between Quebec’s constitution and those of other provinces and it examines critically a proposed Quebec Constitution introduced as a bill in Quebec’s National Assembly in 2007.1 It does so in the context of changing conceptions of constitutions and constitutionalism and infers that the primary purposes of a proposed “new” Quebec Constitution are essentially political and symbolic rather than legal. The adoption of the proposed Constitution should not significantly alter Canada’s constitutional order under Canadian law. It may have a marginal, if any, effect on Quebec’s current constitutional arrangements with Ottawa and the other provinces. On the other hand, if Quebecers embrace such a Constitution, it could lead to two conflicting interpretations of Quebec’s fundamental law with no universally accepted and recognized way of settling the issue. The proposed new Quebec Constitution could serve, perhaps, as a milestone on the road to an independent Quebec state. There is substantial consciousness of and contention regarding the Canadian Constitution but little of its provincial counterparts. In the United States, the central elements of the member states’ constitutional systems are discrete written constitutions unrelated to the federal constitution. This is not so for Canada’s provinces. Canada’s federal and provincial constitutions are interconnected and entangled. Documents of various types make up a part of every province’s constitution, but the most important parts of those constitutions are unwritten. In Canada, an unwritten and obligatory constitutional rule – the convention of responsible government – has been at the core of provincial constitutions.2 This is the requirement that the vice- regally-appointed executive retain the confidence of the popularly elected legislature. -

Le Fédéralisme Multinational: Un Modèle Viable ?

Le fédéralisme multinational est-il un mo- Michel Seymour et Guy Laforest (dir.) dèle d’organisation politique viable ? La disparition de certaines fédérations multinationales comme l’URSS, la Tchécoslovaquie et la Yougoslavie, de même que la mise à mal de certaines autres expé- riences fédérales comme la Belgique et le Canada contrastent singulièrement avec le succès relatif des Michel Seymour est professeur ti- fédérations mononationales comme les États-Unis tulaire au département de philosophie à Le fédéralisme multinational et l’Allemagne. Dès lors, l’expérience européenne l’Université de Montréal. Il a publié De la est-elle prometteuse ? tolérance à la reconnaissance, qui a obtenu Un modèle viable ? Au-delà d’un examen général de la question de le prix du livre 2009 de l’Association ca- l’aménagement de la diversité nationale au sein nadienne de philosophie et le prix Jean- des régimes fédératifs, cet ouvrage se penche plus Charles Falardeau de la Fédération cana- particulièrement sur les problèmes juridiques et po- dienne des sciences humaines. litiques épineux auxquels sont confrontés certains Il a publié précédemment Pensée, langage pays comme le Canada, la Belgique et l’Espagne. et communauté (1994), La nation en question Le fédéralisme multinational. Un modèle viable ? fédéralisme Le viable Un modèle multinational. (1999), Le Pari de la démesure (prix Richard- Existential Communities, Functional Regimes Arès de la revue L’action nationale pour le meilleur essai québécois de l’année 2001) and the Organic Constitution et L’institution du langage (2005). Guy Laforest est professeur titulaire au département de science politique de l’Université Laval. Il étudie la pensée politique et l’histoire intellectuelle en contexte de fédéralisme et de pluralisme national.