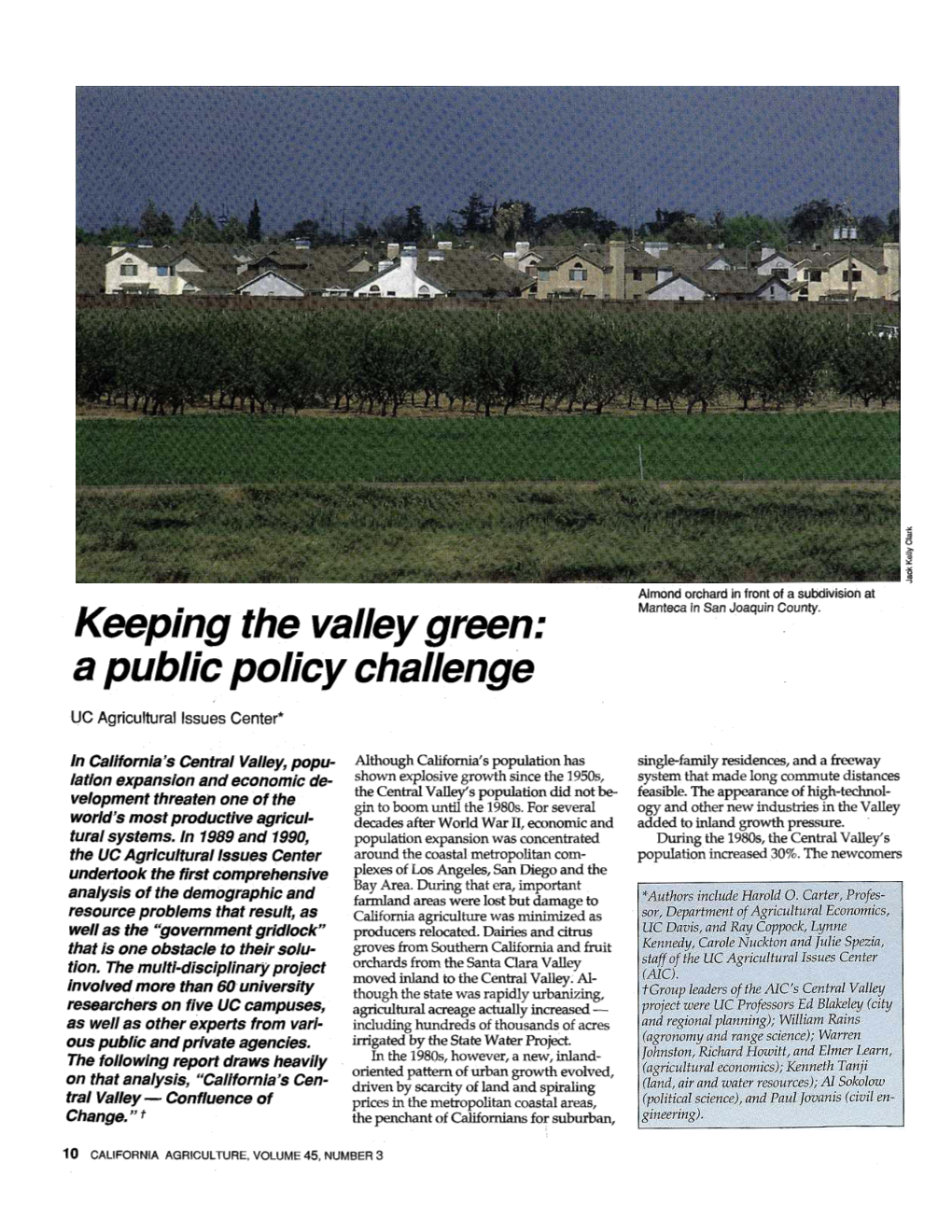

Keeping the Valley Green: a Public Policy Challenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effectiveness of Biopolymer Coagulants in Agricultural

Research Article Efectiveness of biopolymer coagulants in agricultural wastewater treatment at two contrasting levels of pollution Jarno Turunen1 · Anssi Karppinen1 · Raimo Ihme2 © The Author(s) 2019 OPEN Abstract Agricultural difuse pollution is a major environmental problem causing eutrophication of water bodies. Despite the problem is widely acknowledged, there has been relatively few major advances in mitigating the problem. We studied the efectiveness of biopolymer-based (tannin, starch, chitosan) natural coagulants/focculants in treatment of two dif- ferent agricultural wastewaters that difered in their level of phosphorus pollution and turbidity. We used jar-tests to test the efectiveness of the biopolymer coagulants in reducing water turbidity, total phosphorus, and total organic carbon (TOC) from the wastewaters. In more polluted water (total phosphorus: 300 µg/L, turbidity: 130 FNU, TOC: 30 mg/L), all tested biopolymers performed well. The best reductions for diferent biopolymer coagulants were 64–95%, 80–98% and 14–27%, for total phosphorus, turbidity and TOC, respectively. Tannin and chitosan coagulants performed the best at doses of 5–10 mL/L, whereas starch coagulants had the best performance at 1–2 mL/L doses. Tannin and chitosan coagu- lants performed clearly better than the starch coagulants. In less polluted water (total phosphorus: 74 µg/L, turbidity: 3.9 FNU, TOC: 21 mg/L), chitosan and starch coagulants did not produce focs at any of the tested doses. Tannin coagulant performed the best at doses of 5–8 mL/L, where reductions were 70%, 82%, and 22%, for total phosphorus, turbidity and TOC, respectively. The great reductions of phosphorus and turbidity suggests that biopolymer coagulants could be applied in treatment of agricultural water pollution. -

Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters Emerging Policy Solutions

Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters Emerging Policy Solutions Policy HIGHLIGHTS Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters Emerging Policy Solutions “OECD countries have struggled to adequately address diffuse water pollution. It is much easier to regulate large, point source industrial and municipal polluters than engage with a large number of farmers and other land-users where variable factors like climate, soil and politics come into play. But the cumulative effects of diffuse water pollution can be devastating for human well-being and ecosystem health. Ultimately, they can undermine sustainable economic growth. Many countries are trying innovative policy responses with some measure of success. However, these approaches need to be replicated, adapted and massively scaled-up if they are to have an effect.” Simon Upton – OECD Environment Director POLICY H I GH LI GHT S After decades of regulation and investment to reduce point source water pollution, OECD countries still face water quality challenges (e.g. eutrophication) from diffuse agricultural and urban sources of pollution, i.e. pollution from surface runoff, soil filtration and atmospheric deposition. The relative lack of progress reflects the complexities of controlling multiple pollutants from multiple sources, their high spatial and temporal variability, the associated transactions costs, and limited political acceptability of regulatory measures. The OECD report Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters: Emerging Policy Solutions (OECD, 2017) outlines the water quality challenges facing OECD countries today. It presents a range of policy instruments and innovative case studies of diffuse pollution control, and concludes with an integrated policy framework to tackle this challenge. An optimal approach will likely entail a mix of policy interventions reflecting the basic OECD principles of water quality management – pollution prevention, treatment at source, the polluter pays and the beneficiary pays principles, equity, and policy coherence. -

Pesticide Monitoring of Agricultural Soil Pollution

E3S Web of Conferences 193, 01068 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202019301068 ICMTMTE 2020 Pesticide monitoring of agricultural soil pollution Lyudmila Zhichkina1,*, Vladimir Nosov2, Kirill Zhichkin1, Vyacheslav Zhenzhebir2, Yury Abramov2, and Mira Alborova2 1Samara State Agrarian University, 446442 Kinel Uchebnaja str. 2, Samara, Russia 2K.G. Razumovsky Moscow State University of technologies and management, 109004 Moscow Zemlyanoy val 73, Russia Abstract. The role of pesticides in modern agriculture is not in doubt; the continuous improvement of drugs and technologies for their use reduces the possibility of environmental pollution and their accumulation in manufactured products. The purpose of the research is to assess the pollution of the soil cover of agricultural land with residual amounts of pesticides in the Samara region conditions. Tasks: - to analyze the content of insectoacaricides and herbicides residual amounts in the soil in the spring and autumn; - establish patterns of residual pesticides migration along the soil profile. As a result of studies conducted in 2016-2018. it was found that the content of total DDT related to the first hazard class in the studied samples decreases, a similar situation is observed for organochlorine insectoacaricides HCH and HCB, their residual amounts were found in the soil in the autumn and spring periods of 2016. Residual quantities of the organophosphorus insect metacosacaricide were detected annually (the exception was the autumn period of 2017). Regarding the content of residual amounts of herbicides in the soil (2,4-D, dalapon, simazine, atrazine, promethrin, trifluralin, THAN), it can be noted that during the years of research their content was mainly reduced. -

Water Pollution from Agriculture: a Global Review

LED BY Water pollution from agriculture: a global review Executive summary © FAO & IWMI, 2017 I7754EN/1/08.17 Water pollution from agriculture: a global review Executive summary by Javier Mateo-Sagasta (IWMI), Sara Marjani Zadeh (FAO) and Hugh Turral with contributions from Jacob Burke (formerly FAO) Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2017 and the International Water Management Institute on behalf of the Water Land and Ecosystems research program Colombo, 2017 FAO and IWMI encourage the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO and IWMI as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s and IWMI’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence- request or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/ publications) and can be purchased through [email protected]” © FAO and IWMI, 2017 Cover photograph: © Jim Holmes/IWMI Neil Palmer (IWMI) A GLOBAL WATER-QUALITY CRISIS AND THE ROLE OF AGRICULTURE Water pollution is a global challenge that has increased in both developed and developing countries, undermining economic growth as well as the physical and environmental health of billions of people. -

Nitrogen in Agricultural Systems: Implications for Conservation Policy

United States Department of Agriculture Nitrogen in Agricultural Economic Systems: Implications for Research Service Conservation Policy Economic Research Report Marc Ribaudo, Jorge Delgado, LeRoy Hansen, Michael Livingston, Number 127 Roberto Mosheim, and James Williamson September 2011 da.gov .us rs .e w Visit Our Website To Learn More! w w For additional information on nitrogen management and conservation policies, see: www.ers.usda.gov/briefing/agchemicals/ www.ers.usda.gov/briefing/conservationpolicy/ www.ers.usda.gov/briefing/agandenvironment/ Recommended citation format for this publication: Ribaudo, Marc, Jorge Delgado, LeRoy Hansen, Michael Livingston, Roberto Mosheim, and James Williamson. Nitrogen In Agricultural Systems: Implications For Conservation Policy. ERR-127. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Econ. Res. Serv. September 2011. Photo courtesy of USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and, where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. -

Federal Environmental Laws Affecting Agriculture

FEDERAL ENVIRONMENTAL LAWS AFFECTING AGRICULTURE (See NASDA’s website for State Environmental Laws Affecting U.S. Agriculture) A Project of the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture Research Foundation through the National Center for Agricultural Law Research and Information ! ! ! Website: http://www.nasda-hq.org/ under the Research Foundation Section FEDERAL ENVIRONMENTAL LAWS AFFECTING AGRICULTURE Table of Contents This document has two components: the state guide and federal guide. To complete this guide, please download the appropriate state guide also found on NASDA’s website. The Project Participants ................................................... FED-iii Disclaimer ..............................................................FED-iv Quick Reference Guide .................................................... FED-v I. Water Quality ...................................................... FED-1 A. Federal Clean Water Act ....................................... FED-1 1. Overview ............................................. FED-1 2. Water Quality Standards ................................. FED-2 3. NPDES Permits ........................................ FED-3 a. Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations .............. FED-4 b. Unified National Strategy for Animal Feeding Operations . FED-5 4. Wetlands ............................................. FED-5 5. Nonpoint Source Pollution ................................ FED-7 6. Oil Spill Liability ....................................... FED-8 7. Special Programs ...................................... -

Agricultural Pollution of Water Bodies1- 2 William M

50 BARRY B. MILLER Vol. 70 AGRICULTURAL POLLUTION OF WATER BODIES1- 2 WILLIAM M. EDWARDS AND LLOYD L. HARROLD^ ABSTRACT Pollution of Ohio's water bodies is of growing public concern; industrial, urban, and rural sources are becoming the subject of critical examination. Rural sources are soil sediment, plant nutrients, animal waste, and pesticides. Pesticides and phosphorus are absorbed rapidly and strongly to soil particles. Therefore reductions in sediment, phos- phorus, and pesticide pollution are achieved by soil-erosion-control farming practices. More acres need to be brought under erosion-control practices. Nitrates dissolve in water and are carried by surface flow to streams and lakes, and by percolating water to underground aquifers. Increases in the use of nitrogen fertilizer, in evidence almost everywhere, could result in serious contamination of water bodies, if soil enrichment greatly exceeds the crop demand. Areas where large-scale livestock and poultry pro- duction is concentrated are also potential sources of serious pollution. In Ohio, animal- waste pollution problems are being studied at The Ohio State University, and movement of pollutants in surface and subsurface waters on drainage plots near Castalia are being studied by the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center and on agricultural watersheds by USDA Agricultural Research Service at Coshocton, Ohio. INTRODUCTION The rapid increase in pollution of man's environment on earth is the concern of men and nations. Now that space travel appears to be a possibility, great care is being exercised to prevent earth's contamination from reaching other planets. Here at home, state and federal agencies are involved in rapidly expand- ing programs to determine the severity and extent of water and air pollution, their rates of change, sources, and control measures. -

Agricultural Pollution Prevention Resources

Agricultural Pollution Prevention Resources Environmental Management Systems (EMS) Livestock EMS Project The project goal was to develop and evaluate environmental assessment and decision-support aids with which livestock producers can address local priority water and air quality issues. A livestock EMS is a systematic approach to identify, correct and monitor the environmental performance of a livestock enterprise. It involves a continuous cycle of risk assessment, action planning, implementation, review and improvement to fully integrate environmental responsibility into the business of farming. http://www.uwex.edu/AgEMS/livestock/about.html Iowa Soybean Association Certified Environmental Management Systems for Agriculture (CEMSA) is a farmer-led program that is designed to help farmers incorporate an EMS within their farming operation, implement the EMS framework for production agriculture, and assist farmers with documenting and demonstrating measurable environmental quality improvements. http://www.isafarmnet.com/enviroagron/cemsa.html Colorado EMS Permit Program The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) is working to find effective and innovative ways to achieve superior environmental protection though an EMS approach. The pilot project will test a systematic, cross media, outcome based permit system using an approved EMS permit as the vehicle. http://www.cdphe.state.co.us/el/EMS/emspermit/ Montana Environmental Self Assessment for Beef Operations The Montana State University Natural Resources Extension Program has produced a comprehensive environmental checklist for beef cattle operations. Several operations have modified practices and a few have used the assessment to develop EMS approaches. http://animalrangeextension.montana.edu/articles/NatResourc/main-assess.htm Utah State Agriculture Environmental Management Systems The Utah State University Ag Systems Technology and Education program has produced a variety of publications promoting EMS for agricultural production. -

People, More Food, Worse Water?

LED BY LED BY More people, more food, worse water? more food, More people, worse water? more food, More people, Current patternsCurrent patterns of agricultural of agricultural expansion expansion and intensification and intensification are bringing are bringing unprecedented unprecedented environmentalenvironmental externalities, externalities, including including impacts impactson water on quality. water Whilequality. water While pollution water pollution is is slowly startingslowly startingto receive to thereceive attention the attention it deserves, it deserves, the contribution the contribution of agriculture of agriculture to this to this problemproblem has not yethas received not yet received sufficient sufficient consideration. consideration. We needWe a much need bettera much understanding better understanding of the causes of the andcauses effects and of effects agricultural of agricultural water water pollutionpollution as well asas effectivewell as effective means to means prevent to preventand remedy and remedythe problem. the problem. In the existing In the existing literature,literature, information information on water on pollution water pollution from agriculture from agriculture is highly is dispersed. highly dispersed. This report This is report is a comprehensivea comprehensive review and review covers and different covers different agricultural agricultural sectors (includingsectors (including crops, livestock crops, livestock - - a global review of water pollution from agriculture a global review of water pollution -

Exploring the Topics of Soil Pollution and Agricultural Economics: Highlighting Good Practices

agriculture Article Exploring the Topics of Soil Pollution and Agricultural Economics: Highlighting Good Practices Vítor João Pereira Domingues Martinho 1,2 1 Agricultural School (ESAV) and CI&DETS, Polytechnic Institute of Viseu (IPV), 3504-510 Viseu, Portugal; [email protected] 2 Centre for Transdisciplinary Development Studies (CETRAD), University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro (UTAD), 5000-801 Vila Real, Portugal Received: 11 December 2019; Accepted: 14 January 2020; Published: 19 January 2020 Abstract: The evolution of the agricultural sector around the world has generated positive and negative externalities at social, economic and environmental levels. These impacts from the modernization of agriculture would not be, themselves, problematic if the global balance were positive, in sustainable development. However, in some cases, the negative externalities overlap the positive outcomes, namely in soil pollution from the application of fertilizers and crop protection products. From this perspective, the main objective of this study is to explore the relationships between the two following topics: soil pollution and agricultural economics. For this a literature survey was performed from the Web of Science platform based on these two topics put together. From the Web of Science, 45 studies were found and were clustered and explored first through the software VOSviewer. The literature explored with this software was clustered into three groups and shows that the studies related with these topics highlight, namely, three aspects: the problem in question, the benefits and the losses. After this network analysis, the several documents were studied deeper through literature review. Agricultural policies, farmers perceptions, stakeholders’ involvement, farms’ multifunctionality, sustainability and adjusted agricultural practices are all questions to be taken into account in the feedback between soil pollution and agricultural economics. -

Soil Pollution: a Hidden Reality

SOIL POLLUTION: A HIDDEN REALITY THANKS TO THE FINANCIAL SUPPORT OF RUSSIAN FEDERATION SOIL POLLUTION: AHIDDEN ISBN 978-92-5-130505-8 REALITY 9 789251 305058 I9183EN/1/04.18 SOIL POLLUTION AHIDDEN REALITY SOIL POLLUTION AHIDDEN REALITY Authors Natalia Rodríguez Eugenio, FAO Michael McLaughlin, University of Adelaide Daniel Pennock, University of Saskatchewan (ITPS Member) Reviewers Gary M. Pierzynski, Kansas State University (ITPS Member) Luca Montanarella, European Commission (ITPS Member) Juan Comerma Steffensen, Retired (ITPS Member) Zineb Bazza, FAO Ronald Vargas, FAO Contributors Kahraman Ünlü, Middle East Technical University Eva Kohlschmid, FAO Oxana Perminova, FAO Elisabetta Tagliati, FAO Olegario Muñiz Ugarte, Cuban Academy of Sciences Amanullah Khan, University of Agriculture Peshawar (ITPS Member) Edition, Design & Publication Leadell Pennock, University of Saskatchewan Matteo Sala, FAO Isabelle Verbeke, FAO Giulia Stanco, FAO FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2018 DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT Recommended citation Rodríguez-Eugenio, N., McLaughlin, M. and Pennock, D. 2018. Soil Pollution: a hidden reality. Rome, FAO. 142 pp. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

The Coming Freshwater Crisis Is Already Here Don Hinrichsen and Henrylito Tacio

The Coming Freshwater Crisis is Already Here Don Hinrichsen and Henrylito Tacio Don Hinrichsen is an award-winning writer and former journalist who is based in Europe and the United States. He currently works as a writer/media consultant for the UN system. He has also written five books over the past decade on topics ranging from coastal resources to an atlas of the environment. Henrylito D. Tacio is a multi-awarded Filipino journalist who specializes on reporting on science and technology, environment, and agriculture. Tacio currently works as information officer of the Asian Rural Life Development Foundation. Introduction Fresh Water Is A Critical Resource Issue Fresh water is emerging as the most critical resource issue facing humanity. While the supply of fresh water is limited, both the world’s population and demand for the resource continues to expand rapidly. As Janet Abramovitz has written: “Today, we withdraw water far faster than it can be recharged—unsustainably mining what was once a renewable resource” (Abramovitz, 1996). Abramovitz estimates that the amount of fresh water withdrawn for human uses has risen nearly 40-fold in the past 300 years, with over half of the increase coming since 1950 (Abramovitz, 1996). The world’s rapid population growth over the last century has been a major factor in increasing global water usage. But demand for water is also rising because of urbanization, economic development, and improved living standards. Between 1900 and 1995, for example, global water withdrawals increased by over six times—more than double the rate of population growth (Gleick, 1998). In developing countries, water withdrawals are rising more rapidly—by four percent to eight percent a year for the past decade—also because of rapid population growth and increasing demand per capita (Marcoux, 1994).