Capture and Sacrifice at Palenque

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ashes to Caches: Is Dust Dust Among the Heterarchichal Maya?

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Anthropology & Sociology Faculty Publications Anthropology & Sociology 6-2020 Ashes to Caches: Is Dust Dust Among the Heterarchichal Maya? Marshall Joseph Becker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/anthrosoc_facpub Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Volume 28, Issue 3 June 2020 Welcome to the “28 – year book” of The Codex. waxak k’atun jun tun hun Now in its 28th year, The Codex continues to publish materials of substance in the world of Pre-Columbian and Mesoamerican studies. We continue that tradition in this issue. This new issue of The Codex is arriving during a pandemic which has shut down all normal services in our state. Rather than let our members and subscribers down, we decided to go digital for this issue. And, by doing so, we NOTE FROM THE EDITOR 1 realized that we could go “large” by publishing Marshall Becker’s important paper on the ANNOUNCEMENTS 2 contents of caches in the Maya world wherein he calls for more investigation into supposedly SITE-SEEING: REPORTS FROM THE “empty” caches at Tikal and at other Maya sites. FIELD: ARCHAEOLOGY IN A GILDED AGE: THE UNIVERSITY OF Hattula Moholy-Nagy takes us back to an earlier PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM’S TIKAL era in archaeology with her reminiscences of her PROJECT, 1956-1970 days at Tikal in the 1950s and 1960s. Lady by Sharp Tongue got her column in just before the Hattula Moholy-Nagy 3 shut-down happened, and she lets us in on some secrets in Lady K’abal Xook’s past at her GOSSIP COLUMN palace in Yaxchilan. -

With the Protection of the Gods: an Interpretation of the Protector Figure in Classic Maya Iconography

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography Tiffany M. Lindley University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lindley, Tiffany M., "With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2148. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2148 WITH THE PROTECTION OF THE GODS: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE PROTECTOR FIGURE IN CLASSIC MAYA ICONOGRAPHY by TIFFANY M. LINDLEY B.A. University of Alabama, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 © 2012 Tiffany M. Lindley ii ABSTRACT Iconography encapsulates the cultural knowledge of a civilization. The ancient Maya of Mesoamerica utilized iconography to express ideological beliefs, as well as political events and histories. An ideology heavily based on the presence of an Otherworld is visible in elaborate Maya iconography. Motifs and themes can be manipulated to convey different meanings based on context. -

The Rulers of Palenque a Beginner’S Guide

The Rulers of Palenque A Beginner’s Guide By Joel Skidmore With illustrations by Merle Greene Robertson Citation: 2008 The Rulers of Palenque: A Beginner’s Guide. Third edition. Mesoweb: www. mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/PalenqueRulers-03.pdf. Publication history: The first edition of this work, in html format, was published in 2000. The second was published in 2007, when the revised edition of Martin and Grube’s Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens was still in press, and this third conforms to the final publica- tion (Martin and Grube 2008). To check for a more recent edition, see: www.mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/rulers.html. Copyright notice: All drawings by Merle Greene Robertson unless otherwise noted. Mesoweb Publications The Rulers of Palenque INTRODUCTION The unsung pioneer in the study of Palenque’s dynastic history is Heinrich Berlin, who in three seminal studies (Berlin 1959, 1965, 1968) provided the essential outline of the dynasty and explicitly identified the name glyphs and likely accession dates of the major Early and Late Classic rulers (Stuart 2005:148-149). More prominent and well deserved credit has gone to Linda Schele and Peter Mathews (1974), who summarized the rulers of Palenque’s Late Classic and gave them working names in Ch’ol Mayan (Stuart 2005:149). The present work is partly based on the transcript by Phil Wanyerka of a hieroglyphic workshop presented by Schele and Mathews at the 1993 Maya Meet- ings at Texas (Schele and Mathews 1993). Essential recourse has also been made to the insights and decipherments of David Stuart, who made his first Palenque Round Table presentation in 1978 at the age of twelve (Stuart 1979) and has recently advanced our understanding of Palenque and its rulers immeasurably (Stuart 2005). -

Welcome to Cancún, Cozumel & the Yucatán

4 ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Welcome to Cancún, Cozumel & the Yucatán The Yucatán Peninsula captivates visitors with its endless offerings of natural wonders and an ancient culture that’s still very much alive today. Life’s a Beach Nature’s Playground Without a doubt, this corner of Mexico has The Yucatán is the real deal for nature some of the most beautiful stretches of enthusiasts. With colorful underwater coastline you’ll ever see – which explains scenery like none other, it offers some of in large part why beaches get top billing the best diving and snorkeling sites in the on the peninsula. On the east coast you world. Then you have the many biosphere have the famous coral-crushed white sands reserves and national parks that are home and turquoise-blue waters of the Mexican to a remarkably diverse variety of animal Caribbean, while up north you’ll find sleepy and plant life. Just to give you an idea of fishing villages with sandy streets and what’s in store: you can swim with whale wildlife-rich surroundings. For the ultimate sharks, spot crocodiles and flamingos, help beach-bumming experience you can always liberate sea turtles and observe hundreds hit one of several low-key islands off the upon hundreds of bird species. Caribbean coast. Culture & Fun Maya Ruins Galore In case you need a little something more You can’t help but feel awestruck when than pretty beaches, ancient ruins and standing before the pyramids, temples and outdoor adventures, you’ll be glad to know ball courts of one of the most brilliant pre- that culture and fun-filled activities abound Hispanic civilizations of all time. -

Leyenda De Los Soles) to Explain Maya Creations

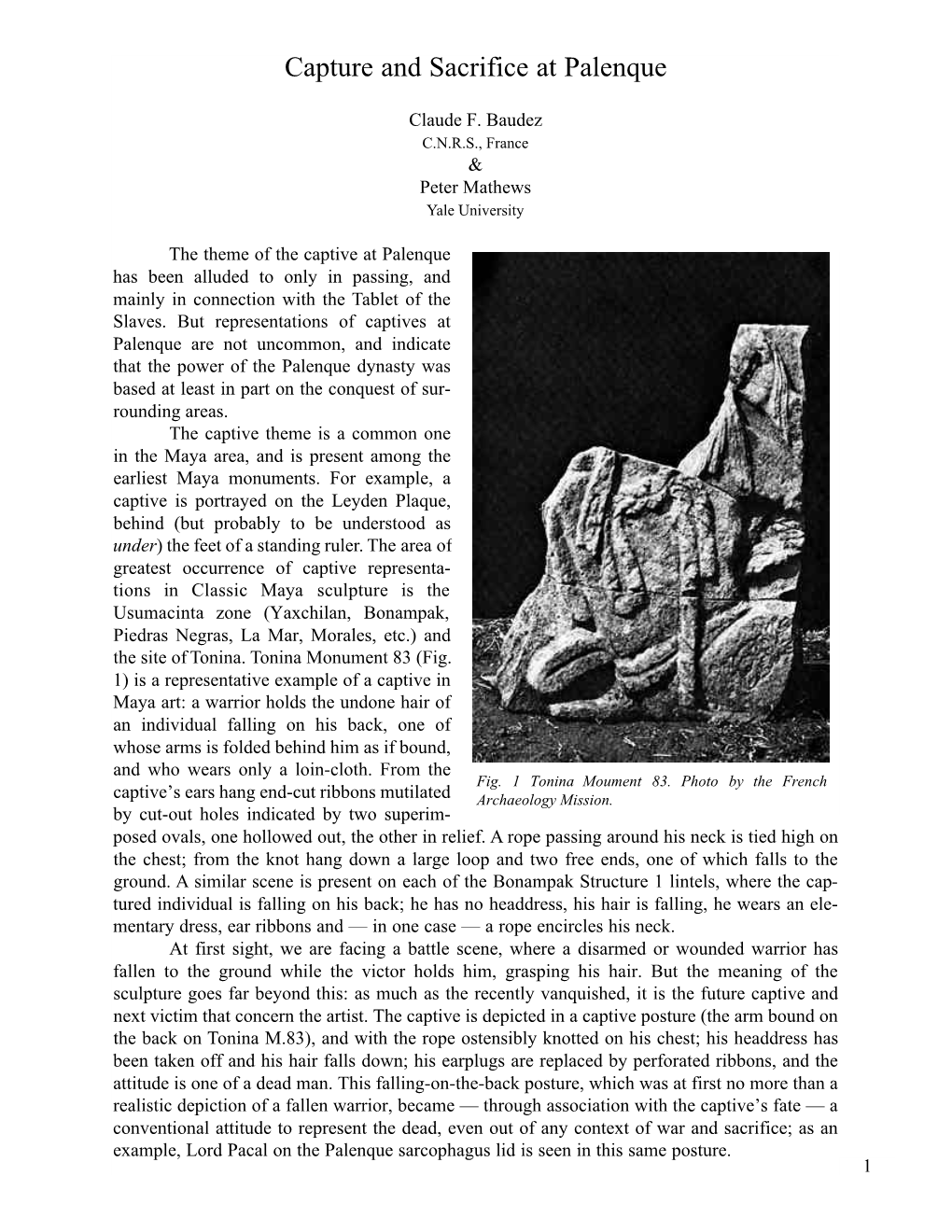

Why we use the Aztec Myth (Leyenda de los Soles) to Explain Maya Creations The surviving accounts of the Maya Creation Myth are fragments, tatters. Much more is missing than is there. The earliest surviving fragments appear on the monuments of Izapa (and neighbors) and the newly‐ discovered Murals of San Bartolo (ca. 100 BCE). As if through a keyhole, we glimpse a rich, intricate cosmology connecting time, space and personalities. It relates the cardinal directions to colors, species of trees and game, the calendar, myths, and who knows what else. Eight centuries later, Classic Maya vase painters illustrate a few other Mythic scenes, some involving the Hero Twins. A few Classic stone inscriptions connect Creation with house‐building. Six centuries later, one of the curiosities Cortez presented to the Emperor, a book we call the Dresden Codex, recounts several arcane events which occurred on 4 Ajaw 8 Kumk’u. Later still, a Quiché Maya scribe in the impoverished and conquered Guatemalan highlands copied out the Popol Vuh, connecting his cacique’s ancestors back to the Creations of the World (ca. 1700). It dwells on the Hero Twins, who prepared the world for its final Creation ‐ our Creation. Though it is clear that the Maya conceived a dizzying, intricately interconnected cosmology, we have difficulty working out its details. This is partly due to the fragmentary nature of our evidence, but it is also increasingly clear that the stories varied substantially from city‐state to city‐state. (Not unlike the conflicting versions of Abraham’s Sacrifice: In the Biblical version, the son is Isaac, who goes on to father the Israelites. -

Solution of the Mayan Calendar Enigma Thomas Chanier

Solution of the Mayan Calendar Enigma Thomas Chanier To cite this version: Thomas Chanier. Solution of the Mayan Calendar Enigma. 2016. hal-01254966v6 HAL Id: hal-01254966 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01254966v6 Preprint submitted on 29 Nov 2016 (v6), last revised 13 Nov 2018 (v7) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. SOLUTION OF THE MAYAN CALENDAR ENIGMA Thomas Chanier∗ Independent researcher, Coralville, Iowa 52241, USA The Mayan arithmetical model of astronomy is described. The astronomical origin of the Mayan Calendar (the 260-day Tzolk'in, the 365-day Haab', the 3276-day Kawil-direction-color cycle and the 1872000-day Long Count Calendar) is demonstrated and the position of the Calendar Round at the mythical date of creation 13(0).0.0.0.0 4 Ahau 8 Cumku is calculated. The results are expressed as a function of the Xultun numbers, four enigmatic Long Count numbers deciphered in the Maya ruins of Xultun, dating from the IX century CE. (Saturno 2012) Evidence shows that this model was used in the Maya Classic period (200 to 900 CE) to determine the Palenque lunar equation. -

Polities and Places: Tracing the Toponyms of the Snake Dynasty

Polities and Places: Tracingthe Toponymsof the Snake Dynasty SIMON MARTIN University of Pennsylvania Museum ERIK VELÁSQUEZ GARCÍA Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México One of the more intriguing and important topics to thonous ones that had at some point transferred their emerge in Maya studies of recent years has been the his- capitals or splintered, each faction laying claim to the tory of the “Snake” dynasty. Research over the past two same title. The landscape of the Classic Maya proves decades has identified mentions of its kings across the to have been a volatile one, not simply in the dynamic length and breadth of the lowlands and produced evi- interactions and imbalances of power between polities, dence that they were potent political players for almost but in the way the polities themselves were shaped by two centuries, spanning the Early Classic to Late Classic historical forces through time. periods.1 Yet this data has implications that go beyond a single case study and can be used to address issues of general relevance to Classic Maya politics. In this brief Placing Calakmul paper we use them to further explore the meaning of The distinctive Snake emblem glyphs and their connection to polities and emblem glyph is ex- places. pressed in full as K’UH- The significance of emblem glyphs—whether they ka-KAAN-la-AJAW or are indicative of cities, deities, domains, polities, or k’uhul kaanul ajaw (Fig- dynasties—has been debated since their discovery ure 1).3 It first came to (Berlin 1958). The recognition of their role as the scholarly notice as one personal epithets of kings based on the title ajaw “lord, of the “four capitals” ruler” (Lounsbury 1973) was the essential first step to listed on Copan Stela A, comprehension (Mathews and Justeson 1984; Mathews a set of cardinally affili- Figure 1. -

Installments 1-10

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute Volume XIII, No. IV, Summer 2013 The Further Adventures of Merle1 MERLE GREENE ROBERTSON In This Issue: The Further Adventures of Merle by Merle Greene Robertson PAGES 1-7 • A Late Preclassic Distance Number by Mario Giron-Ábrego PAGES 8-12 Joel Skidmore Editor [email protected] Marc Zender Associate Editor [email protected] Figure 1. On the Usumacinta River on the way to Yaxchilan, 1965. The PARI Journal 202 Edgewood Avenue “No! You can’t go into the unknown wilds birds, all letting each other know where San Francisco, CA 94117 of Alaska!” That statement from my moth- they are. Evening comes early—dark by 415-664-8889 [email protected] er nearly 70 years ago is what changed my four o’clock. Colors are lost in pools of life forever. I went to Mexico instead, at darkness. Now the owls are out lording it Electronic version that time almost as unknown to us in the over the night, lucky when you see one. available at: U.S. as Alaska. And then later came the But we didn’t wait for nightfall to www.mesoweb.com/ pari/journal/1304 jungle, the jungle of the unknown that I pitch our camp. Champas made for our loved, no trails, just follow the gorgeous cooking, champas for my helpers, and a guacamayos in their brilliant red, yellow, ISSN 1531-5398 and blue plumage, who let you know where they are before you see them, by 1 Editor’s note: This memoir—left untitled by their constant mocking “clop, clop, clop.” the author—was completed in 2010, in Merle’s 97th Mahogany trees so tall you wonder if, year. -

By ROBERT L. RANDS

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology BuUetin 157 Anthropological Papers, No. 48 Some ManifestatioDs of Water in Mesoamerican Art By ROBERT L. RANDS 265 1 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 27 The better established occurrences of water 273 Types of associations 273 The Maya codices 277 The Mexican codices 280 Aztec and Teotihuacdn murals, sculptures, and ceramics 285 Summary 291 The proposed identifications of water 292 Artistic approach to the identifications 292 Non-Maya murals, sculptures, and ceramics 293 Maya murals, sculptures, and ceramics 298 General considerations 298 Highest probability (A) 302 Probability B : paraphernalia and secondary associations 315 Probability B : fang, tongue, or water (?) 320 Artistic typology and miscellany 322 Water and the water lily 330 Conclusions 333 Appendix A. Nonartistic data and current reconstructions 342 Direct water associations : physiological data 342 Water from container 344 Water from mouth 348 Water from eye 348 Water from breast 350 Water from between legs 350 Water from body (pores ?) 350 Water from hand 352 Water from other object held in hand 354 Waterlike design from head 355 Glyph in water 365 Object in water 359 Tlaloc 359 Anthropomorphic Long-nosed God 359 Female water deity 369 Black god (M, B) 360 Miscellaneous anthropomorphic figures 360 Frog 360 Serpent 361 Jaguar (ocelot) 361 Bird 363 Miscellaneous animal 363 Serpentine-saurian monster 364 Detached rear head of monster 364 Other grotesque head, face 365 267 268 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY [Bull. 157 Appendix A. Nonartistic data and current reconstructions—Con. page Death, misfortune, destruction _. 365 Water descending on surface water 365 Water descending on figure 366 The bending-over rainmaker 366 The sky monster and its affiliates 366 Balanced water and vegetation 367 Summary 367 Appendix B. -

The PARI Journal Vol. XII, No. 3

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute Volume XII, No. 3, Winter 2012 Excavations of Nakum Structure 15: Discoveryof Royal Burials and In This Issue: Accompanying Offerings JAROSŁAW ŹRAŁKA Excavations of Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University NakumStructure15: WIESŁAW KOSZKUL Discovery of Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University Royal Burials and BERNARD HERMES Accompanying Proyecto Arqueológico Nakum, Guatemala Offerings SIMON MARTIN by University of Pennsylvania Museum Jarosław Źrałka Introduction the Triangulo Project of the Guatemalan Wiesław Koszkul Institute of Anthropology and History Bernard Hermes Two royal burials along with many at- (IDAEH). As a result of this research, the and tendant offerings were recently found epicenter and periphery of the site have Simon Martin in a pyramid located in the Acropolis been studied in detail and many structures complex at the Maya site of Nakum. These excavated and subsequently restored PAGES 1-20 discoveries were made during research (Calderón et al. 2008; Hermes et al. 2005; conducted under the aegis of the Nakum Hermes and Źrałka 2008). In 2006, thanks Archaeological Project, which has been to permission granted from IDAEH, a excavating the site since 2006. Artefacts new archaeological project was started Joel Skidmore discovered in the burials and the pyramid Editor at Nakum (The Nakum Archaeological [email protected] significantly enrich our understanding of Project) directed by Wiesław Koszkul the history of Nakum and throw new light and Jarosław Źrałka from the Jagiellonian Marc Zender on its relationship with neighboring sites. University, Cracow, Poland. Recently our Associate Editor Nakum is one of the most important excavations have focused on investigating [email protected] Maya sites located in the northeastern two untouched pyramids located in the Peten, Guatemala, in the area of the Southern Sector of the site, in the area of The PARI Journal Triangulo Park (a “cultural triangle” com- the so-called Acropolis. -

Early Explorers and Scholars

1 Uxmal, Kabah, Sayil, and Labná http://academic.reed.edu/uxmal/ return to Annotated Bibliography Architecture, Restoration, and Imaging of the Maya Cities of UXMAL, KABAH, SAYIL, AND LABNÁ The Puuc Region, Yucatán, México Charles Rhyne Reed College Annotated Bibliography Early Explorers and Scholars This is not a general bibliography on early explorers and scholars of Mexico. This section includes publications by and about 19th century Euro-American explorers and 19th and early 20th century archaeologists of the Puuc region. Because most early explorers and scholars recorded aspects of the sites in drawings, prints, and photographs, many of the publications listed in this section appear also in the section on Graphic Documentation. A Antochiw, Michel Historia cartográfica de la península de Yucatan. Ed. Comunicación y Ediciones Tlacuilo, S.A. de C.V. Centro Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del I.P.N., 1994. Comprehensive study of maps of the Yucatan from 16th to late 20th centuries. Oversize volume, extensively illustrated, including 6 high quality foldout color maps. The important 1557 Mani map is illustrated and described on pages 35-36, showing that Uxmal was known at the time and was the only location identified with a symbol of an ancient ruin instead of a Christian church. ARTstor Available on the web through ARTstor subscription at: http://www.artstor.org/index.shtml (accessed 2007 Dec. 8) This is one of the two most extensive, publically available collections of early 2 photographs of Uxmal, Kabah, Sayil, and Labná, either in print or on the web. The other equally large collection, also on the web, is hosted by the Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnography, Harvard Univsrsity (which see). -

High-Precision Radiocarbon Dating of Political Collapse and Dynastic Origins at the Maya Site of Ceibal, Guatemala

High-precision radiocarbon dating of political collapse and dynastic origins at the Maya site of Ceibal, Guatemala Takeshi Inomata (猪俣 健)a,1, Daniela Triadana, Jessica MacLellana, Melissa Burhama, Kazuo Aoyama (青山 和夫)b, Juan Manuel Palomoa, Hitoshi Yonenobu (米延 仁志)c, Flory Pinzónd, and Hiroo Nasu (那須 浩郎)e aSchool of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0030; bFaculty of Humanities, Ibaraki University, Mito, 310-8512, Japan; cGraduate School of Education, Naruto University of Education, Naruto, 772-8502, Japan; dCeibal-Petexbatun Archaeological Project, Guatemala City, 01005, Guatemala; and eSchool of Advanced Sciences, Graduate University for Advanced Studies, Hayama, 240-0193, Japan Edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff, Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, NM, and approved December 19, 2016 (received for review October 30, 2016) The lowland Maya site of Ceibal, Guatemala, had a long history of resolution chronology may reveal a sequence of rapid transformations occupation, spanning from the Middle Preclassic period through that are comprised within what appears to be a slow, gradual transi- the Terminal Classic (1000 BC to AD 950). The Ceibal-Petexbatun tion. Such a detailed understanding can provide critical insights into Archaeological Project has been conducting archaeological inves- the nature of the social changes. Our intensive archaeological inves- tigations at this site since 2005 and has obtained 154 radiocarbon tigations at the center of Ceibal, Guatemala, have produced 154 ra- dates, which represent the largest collection of radiocarbon assays diocarbon dates, which represent the largest set of radiocarbon assays from a single Maya site. The Bayesian analysis of these dates, ever collected at a Maya site.