JASAL 2008 Special Edition.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apocalypse and Australian Speculative Fiction Roslyn Weaver University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2007 At the ends of the world: apocalypse and Australian speculative fiction Roslyn Weaver University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Weaver, Roslyn, At the ends of the world: apocalypse and Australian speculative fiction, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2007. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1733 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] AT THE ENDS OF THE WORLD: APOCALYPSE AND AUSTRALIAN SPECULATIVE FICTION A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ROSLYN WEAVER, BA (HONS) FACULTY OF ARTS 2007 CERTIFICATION I, Roslyn Weaver, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Roslyn Weaver 21 September 2007 Contents List of Illustrations ii Abstract iii Acknowledgments v Chapter One 1 Introduction Chapter Two 44 The Apocalyptic Map Chapter Three 81 The Edge of the World: Australian Apocalypse After 1945 Chapter Four 115 Exile in “The Nothing”: Land as Apocalypse in the Mad Max films Chapter Five 147 Children of the Apocalypse: Australian Adolescent Literature Chapter Six 181 The “Sacred Heart”: Indigenous Apocalypse Chapter Seven 215 “Slipstreaming the End of the World”: Australian Apocalypse and Cyberpunk Conclusion 249 Bibliography 253 i List of Illustrations Figure 1. -

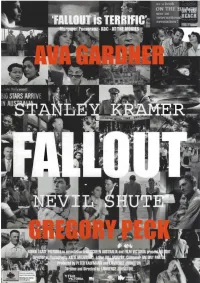

FALLOUT in JAPAN

東京大学アメリカ太平洋研究 第 16 号 7 FALLOUT in JAPAN Peter Kaufmann As producer and co-writer of the feature documentary film, FALLOUT, I was invited by the Center for Pacific and American Studies to present the film at the University of Tokyo last October. Following the screening I was joined on a forum by professors Ms Yuko Kawaguchi from Hosei University and Mr Hidehiro Nakao from Chuo University. Subsequently I was asked to prepare this paper to explain the background, motivation and process for producing FALLOUT. FALLOUT explores the mythology and reality of author Nevil Shute’s post-apocalyptic novel On The Beach, and its Hollywood movie adaptation produced and directed by Stanley Kramer. On The Beach presents a scenario in which most of the world’s population has been annihilated by a nuclear war. A deadly cobalt radioactive cloud has enveloped the earth and is slowly descending on Australia where the last remaining huddle of humanity considers how they will live the final months and days of their lives, and prepare to die. Shute’s novel is eerily prophetic and in it he has projected a nuclear war that is set in 1961, four years into the future from the time of On The Beach’s publication and release in 1957. There are two key factors that were to have a significant influence on me in developing the original concept for FALLOUT, and for realising the film’s central narrative and its eventual production. The setting in the novel for On The Beach is Melbourne, Australia, and it is here that Stanley Kramer filmed his American adaptation on location. -

Remembering on the Beach

A COMMENTARY BY PHILIP BEIDLER Remembering On the Beach efore World War II, Hollywood scared people to death with mad scientists and monsters. During World War II they specialized in strutting Nazis and villainous Japs. After the war, political subversives mixed with Bspace creatures, and vice versa; as importantly, in what had come to be called the nuclear age, a whole new category of fear film centered on atomic mutants: Them; Godzilla; Attack of the Crab Monsters; It Came From Beneath the Sea. More directly, Invasion USA. (1952) combined fear of nuclear attack with communist takeover, helping to usher in the new Cold War genre of Soviet/US atomic mass destruction movies culminating in such boomer classics as Fail Safe and Dr. Strangelove, both issued in 1964. Less frequently remembered, perhaps because slightly older—albeit now decidedly more interesting for its emphasis on the human depiction of nuclear aftermath than on the Pentagon-Kremlin mechanics of initiating wars of mutual annihilation—is the one that first got the attention of popular audiences on the subject. That would beOn the Beach (1959), Stanley Kramer’s elegiac representation of the dying remnant of a world in the wake of global atomic warfare. In the golden age of Technicolor and Cinemascope—and to this degree anticipating its better known successors—it was a black-and-white film of stark, muted, austere genius, featuring career performances from a number of important actors: Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner, a pre-Psycho Anthony Perkins, and Fred Astaire, in his first purely dramatic role. In all these respects, it became a movie that challenged people who saw it never to look at the world in the same way again. -

![R-100 in Canada [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8890/r-100-in-canada-pdf-2238890.webp)

R-100 in Canada [PDF]

Photo Essay Collection The R.100 in Canada By Rénald Fortier Curator, Aviation History, National Aviation Museum © National Aviation Museum 1999 National MuseumAviation Musée nationalde l’aviation i Photo Essay Collection Table of Contents Introduction . .1 The Imperial Airship Scheme . .2 The R.101 . .4 The R.100 . .5 St Hubert . .8 The Flight to Canada . .10 The Flight over Southern Ontario . .15 The Flight to India . .19 Epilogue . .21 Airship Specifications (1929) . .22 National Aviation Museum Photo Essay Collection • The R.100 in Canada 1 Introduction Today, airships are seen as impractical flying machines, as flying dinosaurs useful only during the World Series. The image of the German rigid airship Hindenburg bursting into flames at Lakehurst, New Jersey, in May 1937 is the only knowledge many people have of airships. It was not always this way. Small non-rigid airships, later known as blimps, were used in many early air shows, like the one at Lakeside (now Pointe-Claire) near Montreal, held between 25 June and 5 July 1910, Canada’s very first air show. In July 1919, a British rigid airship, the R.34, became the first flying machine ever to cross the Atlantic from east to west, between England and the U.S., and the first to make a round trip between England and North America. During the late 1920s and early 1930s, the large rigid airship was seen as the only practical way of carrying passengers and mail across the Atlantic and the Pacific. Many schemes were considered; the German transatlantic airship service, made possible by the Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg, is by far the best known among them. -

Nevil Shute's Solent

Nevil Shute's Solent 20th September 2012 - Roy Underdown Pavilion David Henshall gave a fascinating and extremely well researched talk about Nevil Shute’s associations with Hamble and the Solent area. Nevil Shute was one of the world’s best-selling authors of his time, writing classic novels some of which were made into films. Although not a southerner by birth, Nevil Shute ended up making the Solent area his home, as it was an ideal location for him to indulge in the two great loves of his life, sailing and aviation. David started by showing a list of the 24 books he wrote and then highlighted the great number that had connections with Hamble and the Solent area. David said that Nevil Shute was not a great creator but a magpie who cached away snippets of information which he would use in his novels. After the First World War he came to Hamble to sail a yacht which was based at Lukes Boatyard. The yacht had a deep keel and no engine, so he encountered difficulties tacking out of the river and one of his favourite anchorages was inside Calshot Spit. The first time he anchored there, the anchor dragged and he drifted back to Hamble Point buoy. Experiences such as these, including going aground, as well as Lukes Boatyard, the Bugle pub and Hookers bakery at Hamble were used in his books. Nevil Shute wrote his first novel in 1923. He was to have a career as an aeronautical engineer, so sailing out of Hamble he was fascinated by the seaplanes at Hamble Point and he was involved in the setting up of the aviation company ‘Airspeed’, which was eventually based at Portsmouth in the 1930s. -

{Download PDF} What Happened to the Corbetts

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE CORBETTS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nevil Shute Norway | 256 pages | 19 Oct 2009 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099529972 | English | London, United Kingdom What Happened to the Corbetts PDF Book But it wasn't as extreme as I feared it might be, and the main character does treat his wife as a partner more of the time than I expected. When Corbett left, he told Thatcher he was going to Mexico. Indeed, after publication in , a thousand copies of the novel were distributed freely to Air Wardens across the country. Overview Set in , this novel tells the story of the Corbetts, a family preparing for the coming war. An interesting novel written and published shortly before the beginning of World War 2, with the scenario that a war is just beginning, and the effect that bombing raids would have on the general population. If I have held your attention for an evening, if I have given to the least of your officials one new idea to ponder and digest, then I shall feel that this book will have played a part in preparing us for the terrible things that you, and I, and all the cities in this country, may one day have to face together. Corbett's family boards an ocean liner for Canada; because of his nautical experience, Corbett returns to the Victorious to accept a commission as sub-lieutenant from the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve. On February 15, he became convinced that officers of the House were discriminating against him. He was thirty-four years old, a pleasant, ordinary young man of rather a studious turn. -

Reviews of Fallout

REVIEWS OF FALLOUT Cinephilia Review Synopsis: In 1959 Hollywood came to Melbourne in the form of director Stanley Kramer shooting the film adaptation of Neville Shute’s novel, On the Beach, which posits an end of the world scenario in which nuclear war has erupted and Melbourne is waiting for an atomic cloud to travel south and kill the last surviving humans. Fallout is a documentary tracing the story of Shute himself, from his early days in Britain through to his emigration to Australia and the subsequent worldwide response to his novel and the film. Here’s another example of an excellent film picked up by only one local cinema (thank heavens for the Nova!). Fallout works on several interwoven levels – it is at once the story of a famous novelist whose life was filled with fascinating details. It is also a depiction of a more naïve and insular time when a Hollywood movie being made here in Melbourne was the talk of the town, as was the presence of famous stars Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner, Antony Perkins and Fred Astaire. And underlying all this is the ominous theme of Shute’s novel which, when talking today about the still-relevant possible annihilation of the human species, is nothing short of compulsory reading for war-mongers everywhere. The director’s artful use of archival footage is impressive flowing along almost seamlessly into the main narrative. The film hits a nerve from the opening scene in which J.F.K. contemplates in a speech the possibility of nuclear annihilation and we then see the iconic image of a billowing exploding A-bomb. -

The R.101 Story: a Review Based on Primary Source Material and First Hand Accounts

Journal of Aeronautical History Paper No. 2015/02 The R.101 story: a review based on primary source material and first hand accounts by Peter Davison BA(hons) AMRAeS The editorial assistance of Dr Giles Camplin and Mr Crispin Rope is acknowledged. Abstract The airship R.101 was designed and built at the Royal Airship Works, Cardington, under the Imperial Airship Scheme, to shorten journey times to the Dominions. It crashed near Beauvais in northern France at 2.08am on 5th October 1930 while on a proving flight to Karachi (then in India). After hitting the ground, the airship caught fire, killing 48 of the 54 persons on board, including the Secretary of State for Air, Lord Christopher Thomson. This paper describes the development of the R.101, the background to the Imperial Airship Scheme, the accident and the subsequent Inquiry, largely through quotations from contemporary documents, both official and personal, and interviews with people involved. Preface This paper is the result of a long period of research into the circumstances relating to the Imperial Airship Scheme and the loss of the R.101 in October 1930 during a proving flight to India. Rather than subject myself to the limitations of commercial publishing and with regard to the limited market for the subject at this depth, the authors have decided to place unbound copies with the major archives in the UK for the benefit of future researchers. The paper cannot be conclusive due to uncertainty over the precise cause of the accident and the loss of all those on board with detailed knowledge of the final few minutes over France. -

An Old Captivity: Nevil Shute’S Requiem for the Golden Age of Aviation

87 PLURAL SPACES, FICTIONAL MYSTERIES AN OLD CAPTIVITY: NEVIL SHUTE’S REQUIEM FOR THE GOLDEN AGE OF AVIATION FRED ERISMAN Texas Christian University Abstract: In 1940, the British engineer Nevil Shute Norway, writing as “Nevil Shute”, published An Old Captivity. Although the Second World War had begun, Shute chose to look backward, invoking for one last time the romance and excitement of the Golden Age of Aviation (1925-1940). Writing of a small-scale Arctic expedition and a mysterious dream linking two young people, he uses an important civil airplane, two moments of British national eminence in aviation, and an episode of trans-Atlantic flight to characterize the Golden Age. He poignantly invokes an era quickly vanishing, its excitement and innocence destroyed by war. Keywords: British aviation history, “Golden Age of aviation”, MacRobertson Race, Nevil Shute, World War II 1. Introduction When the British engineer-turned-author Nevil Shute (1899-1960) settled down to write his sixth novel, An Old Captivity (1940), Europe was going to pieces around him. Shute began his actual writing in 1939; by that time he had seen the German annexation of Czechoslovakia, the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, and the world’s first experience of Blitzkrieg. As the German invasion of Poland began in September of 1939, waves of Ju-87 and He-111 bombers destroyed air defenses and Bf-109 fighters assured air superiority, while the air attacks were coordinated with mechanized Panzer units that swept across the country’s borders and crushed all ground resistance. The coming of a new kind of war was obvious to all, and only the question of where and when remained (Roberts 2011: passim). -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} in the Wet by Nevil Shute in the Wet

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} In the Wet by Nevil Shute In the Wet. All our eBooks are FREE to download! sign in or create a new account. EPUB 340 KB. Kindle 470 KB. $2.99. Support epubBooks by making a small PayPal donation purchase . This work is available in the U.S. and for countries where copyright is Life+50 or less. Description. Shute’s speculative glance into the future of the British Empire. An elderly clergyman stationed in the Australian bush is called to the bedside of a dying derelict. In his delirium Stevie tells a story of England in 1983 through the medium of a squadron air pilot in the service of Queen Elizabeth II. It is the rainy season. Drunk and delirious, an old man lies dying in the Queensland bush. In his opium-hazed last hours, a priest finds his deserted shack and listens to his last words. Half-awake and half-dreaming the old man tells the story of an adventure set decades in the future, in a very different world… 443 pages, with a reading time of. 6.75 hours (110,983 words) , and first published in 1953. This DRM-Free edition published by epubBooks , 2015 . Community Reviews. Your Review. Sign up or Log in to rate this book and submit a review. There are currently no other reviews for this book. Excerpt. I have never before sat down to write anything so long as this may be, though I have written plenty of sermons and articles for parish magazines. I don’t really know how to set about it, or how much I shall have to write, but as nobody is very likely to read it but myself perhaps that is of no great consequence. -

In Search of Nevil Shute

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries 10-1971 In Search of Nevil Shute Julian Smith Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the European History Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Julian. "In Search of Nevil Shute." The Courier 9.1 (1971): 8-13. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stephen Crane in 1893. Photograph by Corwin Knapp Linson, artist, friend of Crane, and author ofMy Stephen Crane (Syracuse University Press, 1958). From the Stephen Crane Papers, George Arents Research Library. THE COURIER SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES VOLUME IX, NUMBER 1 OCTOBER, 1971 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page The Modernity of Stephen Crane's Poetry: A Centennial Tribute Walter Sutton 3 In Search of Nevil Shute Jutian Smith 8 Preliminary Calendar of the Nevil Shute Norway Manuscripts Microfilm Howard L. Applegate 14 Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, American Sculptor 21 The Management of a University Library Roger H. McDonough 36 Asa Eastwood and His Diaries, 1806-1870 Faye Dudden 42 Open for Research ... Notes on Collections 51 News of Library Associates 54 1 In Search of Nevil Shute by Julian Smith Because it contains much unpublished autobiographical material and early or variant drafts of his published fiction, the Nevil Shute Norway manuscript collection on microfilm at Syracuse University offers an unusually fine chance to study in depth a popular writer who brought pleasure to millions of readers through a career spanning three decades. -

Nevil Shute Booklet

NEVILNEVIL SHUTESHUTE GatheringGathering CapeCod2005 October 2-6 Hyannis, Massachusetts USA “We Shall Remember Them” Welcome! Dear Fellow Shutists: Welcome to the 4th Nevil Shute Gathering! We are so pleased that you have come to Cape Cod for this event. We are looking forward seeing all of you. Now that our 50th wedding celebration has past with all 17 family members gathered in France, we have one more wonderful event to take place and you are the main attraction. After looking at many hotels we felt that the Cape Codder was just what we were looking for. It is family owned, not too big or too small and is a comfort- able, relaxing site to hold our meeting. We hope you will feel the same. Don’t forget to enjoy the Wave Pool! You may like to make an appointment to be pam- pered at the Spa or work your muscles in the exercise room. Just a REMINDER, you are on your own for breakfast and on Monday and Tuesday for evening dinners. A nice restaurant, the Hearth and Kettle, is here at the hotel or, if you want to take a short walk (exiting to your right from the hotel), you will find seafood at Cooke’s or a family style restaurant at Friendly’s. There are additional restaurants along Rt 132 but you will need to drive. Please take a few minutes to look over your Program Book. We have wonder- ful speakers who have worked long and hard on their presentations. The exhibits have been thoughtfully brought by many participants.