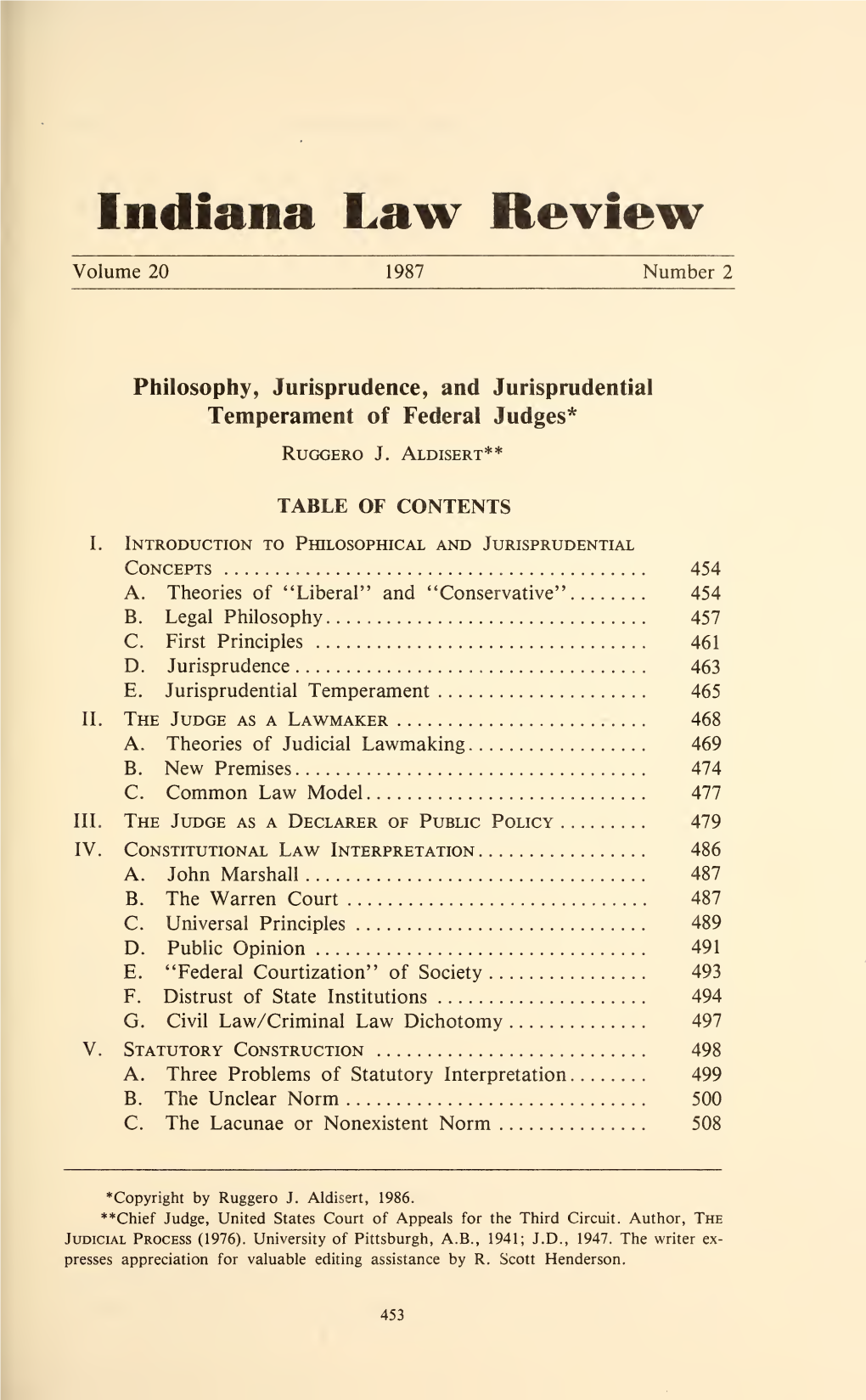

INDIANA LAW REVIEW [Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metaphysics Today and Tomorrow*

1 Metaphysics Today and Tomorrow* Raphaël Millière École normale supérieure, Paris – October 2011 Translated by Mark Ohm with the assistance of Leah Orth, Jon Cogburn, and Emily Beck Cogburn “By metaphysics, I do not mean those abstract considerations of certain imaginary properties, the principal use of which is to furnish the wherewithal for endless dispute to those who want to dispute. By this science I mean the general truths which can serve as principles for the particular sciences.” Malebranche Dialogues on Metaphysics and Religion 1. The interminable agony of metaphysics Throughout the twentieth century, numerous philosophers sounded the death knell of metaphysics. Ludwig Wittgenstein, Rudolf Carnap, Martin Heidegger, Gilbert Ryle, J. L. Austin, Jacques Derrida, Jürgen Habermas, Richard Rorty, and, henceforth, Hilary Putnam: a great many tutelary figures have extolled the rejection, the exceeding, the elimination, or the deconstruction of first philosophy. All these necrological chronicles do not have the same radiance, the same seriousness, nor the same motivations, but they all agree to dismiss the discipline, which in the past was considered “the queen of the sciences”, with a violence at times comparable to the prestige it commanded at the time of its impunity. Even today, certain philosophers hastily spread the tragic news with contempt for philosophical inquiry, as if its grave solemnity bestowed upon it some obviousness. Thus, Franco Volpi writes: ‘Grand metaphysics is dead!’ is the slogan which applies to the majority of contemporary philosophers, whether continentals or of analytic profession. They all treat metaphysics as a dead dog.1 In this way, the “path of modern thought” would declare itself vociferously “anti- metaphysical and finally post-metaphysical”. -

The Gnosiology As Experience of the Resurrected Christ in the Liturgical Texts of the Pentecostarion

The Gnosiology as experience of the Resurrected Christ in the liturgical texts of the Pentecostarion CONTENT INTRODUCTION 4 The motif for choosing the theme 4 The stage of the theme`s research 5 The used method 5 The purpose of the research 5 Terminological clarifications 6 CHAPTER I. THE PENTECOSTARION – THE HYMNOGRAPHICAL IMAGE OF 11 THE STATE OF RESURRECTION IN JESUS CHRIST 1.1. The Pentecostarion – the Church`s Book of Cult 11 1.2. The Pentecostarion – the Relation Dogma – Cult – Knowledge 24 1.2.1. The Cult, Favorable Environment for Spreading the Faith and for Knowing the Dogma 27 1.2.2. The Church`s Cult, Guardian of the Dogma Against Heresy 30 1.2.3. The Dogma, the Cult and the Spiritual Knowledge 33 1.3. The Pentecostarion – the Doxological Dimension of the Knowledge 36 CHAPTER II. THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL FUNDAMENTALS OF THE ORTHODOX 51 GNOSIOLOGY MIRRORED IN PENTECOSTARION 2.1. Revelation and Knowledge 51 2.2. Image and Likeness of the Power of the Man of Knowing God 63 2.2.1. The Falling into Sin and the Image Corrupted through Passions 67 2.2.2. The Renewal of the Engulfed by Passion Image 68 2.3. Person - Communion - Knowledge 75 CHAPTER III THE CHRISTOLOGICAL FUNDAMENTALS OF THE ORTHODOX 84 GNOSIOLOGY MIRRORED IN PENTECOSTARION 1 3.1. The Man`s Healing into Christ – Premise of the Knowledge 84 3.1.1. The Embodiment of the Son of God 84 3.1.1.1. Jesus Christ True God and True Man 90 3.1.1.2. The Deification of the Human Nature into Christ 91 3.1.1.3. -

Theoretical Analysis of Depreciation in Municipalities (Gnosiology, Ontology and Epistemology)

Trakia Journal of Sciences, Vol. 17, Suppl. 1, pp 524-529, 2019 Copyright © 2019 Trakia University Available online at: http://www.uni-sz.bg ISSN 1313-7069 (print) ISSN 1313-3551 (online) doi:10.15547/tjs.2019.s.01.083 THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF DEPRECIATION IN MUNICIPALITIES (GNOSIOLOGY, ONTOLOGY AND EPISTEMOLOGY) D. Velikov* Department of Finance and Management, Plovdiv University "Paisii Hilendarski", Plovdiv, Bulgaria ABSTRACT The amortization charge leads to an improvement in the quality of accountability and public finance statistics. Accounting analysis is part of the information function of accounting. The aim of the publication is to analyze depreciation in municipalities and to propose a synthesis of properties and a summary of common features, trends and laws. The ontological nature of depreciation in accounting science presents the main problems solved by accounting for depreciation. Epistemological coverage of depreciation covers its origin, scope and peculiarities. The research methods are analysis and synthesis, comparison, analogy, modeling, systematization and summary, comparative and group accounting analysis. The results obtained are presented in tabular form. The conclusion is that by switching from a smaller range of the signage coverage of the unit to the depreciation in municipalities, we are targeting a wider range of sign coverage, pointing out the qualities of the different categories of depreciation in the municipalities as an internal definition and an external manifestation. Key words: depreciation, theoretical analysis, accounting, public sector, category, quality. INTRODUCTION expression of the systematic distribution of the The accrual of depreciation in the public sector depreciable value of the asset over its last life. leads to an improvement in the quality of The subject of the survey is the normative accountability and public finance statistics. -

Pop Compact Disc Releases - Updated 08/29/21

2011 UNIVERSITY AVENUE BERKELEY, CA 94704, USA TEL: 510.548.6220 www.shrimatis.com FAX: 510.548.1838 PRICES & TERMS SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE INTERNATIONAL ORDERS ARE NOW ACCEPTED INTERNATIONAL ORDERS ARE GENERALLY SHIPPED THRU THE U.S. POSTAL SERVICE. CHARGES VARY BY COUNTRY. WE WILL ALWAYS COMPARE VARIOUS METHODS OF SHIPMENT TO KEEP THE SHIPPING COST AS LOW AS POSSIBLE PAYMENT FOR ORDERS MUST BE MADE BY CREDIT CARD PLEASE NOTE - ALL ITEMS ARE LIMITED TO STOCK ON HAND POP COMPACT DISC RELEASES - UPDATED 08/29/21 Pop LABEL: AAROHI PRODUCTIONS $7.66 APCD 001 Rawals (Hitesh, Paras & Rupesh) "Pehli Nazar" / Pehli Nazar, Meri Nigahon Me, Aaja Aaja, Me Dil Hu, Tujhko Banaya, Tujhko Banaya (Sad), Humne Tumko, Oh Hasina, Me Tera Hu Diwana (ADD) LABEL: AUDIOREC $6.99 ARCD 2017 Shreeti "Mere Sapano Mein" (Music: Rajesh Tailor) Mere Sapano Mein, Jatey Jatey, Ek Khat, Teri Dosti, Jaan E Jaan, Tumhara Dil - 2 Versions, Shehenayi Ke Soor, Chalte Chalte, Instrumental (ADD) $6.99 ARCD 2082 Bali Brahmbhatt "Sparks of Love" / Karle Tu Reggae Reggae, O Sanam, Just Between You N Me, Mere Humdum, Jaana O Meri Jaana, Disco Ho Ya Reggae, Jhoom Jhoom Chak Chak, Pyar Ke Rang, Aag Ke Bina Dhuan Nahin, Ja Rahe Ho / Introducing Jayshree Gohil (ADD) LABEL: AVS MUSIC $3.99 AVS 001 Anamika "Kamaal Ho Gaya" / Kamaal Ho Gaya, Nach Lain De, Dhola Dhol, Badhai Ho Badhai, Beetiyan Kahaniyan, Aa Bhi Ja, Kahaan Le Gayee, You & Me LABEL: BMG CRESCENDO (BUDGET) $6.99 CD 40139 Keh Diya Pyar Se / Lucky Ali - O Sanam / Vikas Bhalla - Dhuan, Keh Diya Pyar Se / Anaida - -

NET.WORX 46 | Sprachliche Und Textuelle Merkmale in Weblogs. Ein

Peter Schlobinski & Torsten Siever (Hrsg.) Sprachliche und textuelle Merkmale in Weblogs. Ein internationales Projekt Mit Beiträgen von Mario Franco, Marta de Gerdes, Małgorzata Kowalczyk, Sandro M. Moraldo, Helena Pettersson, Peter Schlobinski & Torsten Siever, Larissa Shchipitsina, Bernd Sieberg und Jia Zhu ›› 46 DIENET.WORX ONLINE-SCHRIFTENREIHE DES PROJEKTS SPRACHE@WEB Networx ist die Online-Schriftenreihe des Projekts NET.WORX Sprache@web. Die Reihe ist eine ein- getragene Publikation beim Nationalen REdaktIoN ISSN-Zentrum der Deutschen Bibliothek www.mediensprache.net | [email protected] in Frankfurt am Main. Die genauen Anschriften und E-Mail-Adressen siehe weiter unten HerausgEber Jens Runkehl, Peter Schlobinski, Torsten Siever » Einsenden? EdItorial-boaRd Prof. Dr. Jannis Androutsopoulos (Universität Hannover) für den Bereich websprache & medienanalyse; Möchten Sie eine eigene Arbeit bei uns Prof. Dr. Christa Dürscheid (Universität Zürich) für den veröffentlichen? Dann senden Sie uns Bereich Handysprache; ihren Text an folgende E-Mail-Adresse: Prof. Dr. Nina Janich (Technische Universität Darmstadt) für [email protected] den Bereich Werbesprache; Prof. Dr. Ulrich Schmitz (Universität Essen), für den Bereich Websprache. ISSN 1619-1021 » Homepage Anschrift Niedersachsen: Universität Hannover, Deutsches Seminar, Königsworther Platz 1, 30167 Hannover Alle Arbeiten der Networx-Reihe sind Hessen: Technische Universität Darmstadt, Institut für kostenlos im Internet downloadbar unter: Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaft, Hochschulstrasse 1, 64823 Darmstadt http://www.mediensprache.net/networx/ Internet: www.mediensprache.net/networx/ E-Mail: [email protected] Zu dieser Arbeit autor & TitEl Schlobinski, Peter & Torsten Siever (Hrsg.): Sprachliche und textuelle Merkmale in Weblogs. Ein internationales Projekt. VersIoN 1.1 (2005-01-13) ZItierweisE Schlobinski, Peter & Torsten Siever (Hrsg., 2005): Sprachliche Copyright und textuelle Merkmale in Weblogs. -

Human Rights in Contemporary Africa

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1964 Human Rights in Contemporary Africa Denis V. Cowen Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Denis V. Cowen, "Human Rights in Contemporary Africa," 9 Natural Law Forum 1 (1964). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUMAN RIGHTS IN CONTEMPORARY AFRICA A Case Study of the Sources of Their Validity, Their Rationale, Their Place in a Hierarchy of Values, Their Relation to the Sense of Justice, and Their Potential Efficacy* Denis V. Cowen IN AN ARTICLE on African legal studies which I contributed recently to Law and Contemporary Problems, I was rash enough to say: Sooner or later in any really serious discussion of human rights and their protection, the foundations of the subject will be probed. At that point, lawyers may perhaps be forgiven for not being adherents of natural law in the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition, but it is less pardon- able if their condition is based on an assured and glassy ignorance, on equating Rousseau with, say, St. Thomas, or John Locke with Hooker, or Descartes with Socrates.' In retrospect these words of mine have a high-minded ring, an almost aggressive quality, which makes me catch my breath; nor perhaps is it suffi- cient excuse to say that when I wrote them I had recently been irritated by a man who told me that, during his professional career, he had met quite a number of well-meaning people who seemed to imagine that there was something in so-called natural law; but that not one of them could even begin to give an example of either a natural law or a natural right. -

Life Beyond Wheels

UNITED SPINAL ASSOCIATION’S life beyond wheels newmobility.com NOV 2019 $4 for Pressure Injuries SofTech Cushion NOW FEATURING Bluetooth Wireless Technology Shown without included cover HCPCS code E2609 AquilaCorp.com 8667829658 ADVERTORIAL “ I feel more like I did before my accident – an independent 26-year-old man” Thomas*, catheter user After his accident, Thomas had to rely on other people to help him catheterize. With SpeediCath® Compact Set, he’s gotten back his independence.** Once his initial rehab was over, It’s now the only product he uses Thomas, 26, was determined to get when catheterizing himself and out and about and meet friends. The Thomas is particularly happy about its only issue was his injury meant a discreet size and the hydrophilic caregiver, friend, or relative had to coating , which makes the catheter help him catheterize. He explains: “I pre-lubricated. He goes on: “The couldn’t be spontaneous – it was like reason it’s so much easier is there are an anchor keeping me down.” so few steps involved – you don’t have to lubricate it, or push through the From the start, Thomas preferred bag. The catheter’s already out so intermittent catheters and felt they you just put it right in and you’re good offered more control than an to go.” indwelling product. But the problem was finding one he could open “It’s easier to keep more of them in a himself. He adds: “My occupa tional bag, and they’re easier to handle and therapist suggested SpeediCath use. It goes into the bladder easier Compact Set, but I couldn’t open it at and with less resistance, and the About SpeediCath Compact Set first. -

One with God: Salvation As Deification and Justification PDF Book

ONE WITH GOD: SALVATION AS DEIFICATION AND JUSTIFICATION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Veli-Matti Karkkainen | 152 pages | 01 Jan 2005 | Liturgical Press | 9780814629710 | English | Collegeville, MN, United States One with God: Salvation as Deification and Justification PDF Book Scottish Journal of Theology 63 3 : Retrieved 10 January Advanced Search Links. Bestselling Series. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. Further information: Christian contemplation. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. The goal of the Christian life was union with God in perfect love and holiness. Through theoria illumination with or direct experience of the Triune God , human beings come to know and experience what it means to be fully human, i. Retrieved 11 June — via Myriobiblos. Cambridge, UK: James Clarke, pp. Torrance TF. A person must fashion his life to be a mirror, a true likeness of God. Outline of Christian theology Christianity portal. In One With God Karkkainen points out that amidst all the differences between the East and West with regard to theological orientations and the language and concepts for soteriology, there is a common motif to be found: union with God. Eastern Orthodox Church. Popular Patristics Series. Joanna Leidenhag 1. Holy Things: A Liturgical Theology. In recent decades the doctrine of salvation has become a key issue in international ecumenical conversations between Lutherans and Roman Catholics and also between Lutherans and Eastern Orthodox. Part of a series on. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster. God and the Gift Risto Saarinen. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. A common analogy for theosis , given by the Greek fathers, is that of a metal which is put into the fire. -

![[, Maurice Cornforth] E a Crítica Marxista Ao Pragmatismo 67 Panhamento No Título (Que Nada Mais Terá De Misterioso)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7639/maurice-cornforth-e-a-cr%C3%ADtica-marxista-ao-pragmatismo-67-panhamento-no-t%C3%ADtulo-que-nada-mais-ter%C3%A1-de-misterioso-1257639.webp)

[, Maurice Cornforth] E a Crítica Marxista Ao Pragmatismo 67 Panhamento No Título (Que Nada Mais Terá De Misterioso)

V M-V [, M C] P Paulo Antunes1 (Universidade de Lisboa) É no processo da atividade prática, sobre as bases das necessidades materiais da vida da sociedade (não na prática con- cebida de um modo limitado, reduzida à experiência e ao experi- mento, não na prática concebida no espírito do subjetivismo dos pragmatistas e instrumentalistas) que não só se têm aperfeiçoado historicamente os próprios órgãos dos sentidos humanos e se os tem prolongado pela técnica, como se desenvolve o pensamento abstrato com base na linguagem e que, instância decisória, se verifi ca em que dose e até que ponto é ou pode ele ser, dentro de quadros sociais históricos determinados, fi dedigno e verdadeiro. Vasco de Magalhães-Vilhena, 1964. § 1. Notas preambulares: em memória de Vasco de Magalhães-Vilhena Antes de começar, gostava de cumprimentar todos os presentes di- zendo que é com enorme satisfação que me encontro aqui a prestar home- nagem a Vasco de Magalhães-Vilhena (1916-1993) que já só me chegou através dos seus escritos, o que porventura muito honrará a quem fez do 1 [email protected] Philosophica, 49, Lisboa, 2017, pp. 65-78. 66 Paulo Antunes pensamento e da escrita parte essencial da sua vida2. Avancemos que o tempo é escasso para delongas. A comunicação que vos apresento, mais do que tomar como objeto a bibliografi a e/ou biografi a do homenageado ou apresentar sucintamente um tema ou temas que o cativaram, pretende, antes, servir-se de uma ou outra referência episódica dos seus textos. Para o caso, a comunicação pre- tende servir-se das referências que remetem, como o título anuncia, para a crítica marxista ao Pragmatismo. -

On the Phases of Reism §1. Introduction

On the Phases of Reism1 BARRY SMITH §1. Introduction Along with almost all the more important Polish philosophers of the twentieth century, Kotarbiński, too, was a student of Kasimir Twardowski, and it is Twardowski who is more than anyone else responsible for the rigorous thinking and simplicity of expression that is so characteristic of Kotarbiński’s work. Twardowski was of course himself a member of the Brentanist movement, and the influence of Brentanism on Kotarbiński’s writings reveals itself clearly in the fact that the ontological theories which Kotarbiński felt called upon to attack in his writings were in many cases just those theories defended either by Twardowski or by other thinkers within the Brentano tradition. Leśniewski, too, inherited through Twardowski an interest in Brentano and his school, and as a young man he had conceived the project of translating into Polish the Investigations on General Grammar and Philosophy of Language of Anton Marty, one of Brentano’s most intimate disciples. Leśniewski, as he himself expressed it, grew up “tuned to general grammar and logico-semantic problems à la Edmund Husserl and the representatives of the so-called Austrian School”. (1927/31, p. 9) The influence of Brentanism on Polish analytic philosophers such as Kotarbiński and Leśniewski has, however, been largely overlooked– principally as a result of the fact that the writings of the Polish analytic school have been perceived almost exclusively against the background of Viennese positivism or of Anglo-Saxon analytic philosophy. It is hoped that the present paper, following in the footsteps of Jan Woleński’s recent work,2 might do something to help rectify this imbalance. -

Delicate Affections

DDDDeeeelllliiiiccccaaaatttteeee AAffffffffeeeeccccttttiiiioooonnnnssss by Adrian Saldanha Let me take you away, for a moment, to a place far from here. A lush green forest meadow grows with patches of exquisite wildflowers blossoming everywhere — a veritable paradise on earth. In the middle of it all is a tiny, crystal clear pond that reflects the light that falls on it. The pond isn't very deep, and you can see the assortment of pebbles at the bottom of it. From that pond stems a wandering stream that ventures further into the wilderness. The grass beneath your feet is thick and a very healthy shade of green. The trees are tall and mighty, a worthy inspiration with their vast grandeur, and between some of the high branches, great rays of sunlight manage to shine through into the forest and create a nearly holy and spiritual glow. The very sight of it is so beautiful and soothing; it makes you wonder how some divine force in the universe could not exist. In the morning, you and I are together. The songbirds sing their tunes melodically, as the world gently wakes up. Despite its great solace, however, you and I are too restless. We quickly amuse ourselves by trying to climb the trees, toss pebbles into the pond, and chase one another throughout the wilderness. We haven't a care in the world, and I find myself unable to admire the calmness of meadow, for I am too busy admiring your beauty and your grace, as you're basked in that gentle morning light. My heart races and skips because I know I am in love, though I dare not say a word, for I know not how you feel yourself. -

BB-1971-12-25-II-Tal

0000000000000000000000000000 000000.00W M0( 4'' .................111111111111 .............1111111111 0 0 o 041111%.* I I www.americanradiohistory.com TOP Cartridge TV ifape FCC Extends Radiation Cartridges Limits Discussion Time (Based on Best Selling LP's) By MILDRED HALL Eke Last Week Week Title, Artist, Label (Dgllcater) (a-Tr. B Cassette Nos.) WASHINGTON-More requests for extension of because some of the home video tuners will utilize time to comment on the government's rulemaking on unused TV channels, and CATV people fear conflict 1 1 THERE'S A RIOT GOIN' ON cartridge tv radiation limits may bring another two- with their own increasing channel capacities, from 12 Sly & the Family Stone, Epic (EA 30986; ET 30986) month delay in comment deadline. Also, the Federal to 20 and more. 2 2 LED ZEPPELIN Communications Commission is considering a spin- Cable TV says the situation is "further complicated Atlantic (Ampex M87208; MS57208) off of the radiated -signal CTV devices for separate by the fact that there is a direct connection to the 3 8 MUSIC consideration. subscriber's TV set from the cable system to other Carole King, Ode (MM) (8T 77013; CS 77013) In response to a request by Dell-Star Corp., which subscribers." Any interference factor would be mul- 4 4 TEASER & THE FIRECAT roposes a "wireless" or "radiated signal" type system, tiplied over a whole network of CATV homes wired Cat Stevens, ABM (8T 4313; CS 4313) the FCC granted an extension to Dec. 17 for com- to a master antenna. was 5 5 AT CARNEGIE HALL ments, and to Dec.