Is Gender Inequality a Barrier to Economic Growth? a Panel Data Analysis of Developing Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bosnia and Herzegovina and the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework

Bosnia and Herzegovina and the United Nations 2021- Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework 2025 A Partnership for Sustainable Development Declaration of commitment The authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and the United Nations (UN) are committed to working together to achieve priorities in BiH. These are expressed by: ` The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and selected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and targets1 as expressed in the emerging SDG Framework in BiH and domesticated SDG targets2; ` Future accession to the European Union, as expressed in the Action Plan for implementation of priorities from the European Commission Opinion and Analytical Report3; ` The Joint Socio-Economic Reforms (‘Reform Agenda’), 2019-20224; and ` The human rights commitments of BiH and other agreed international and regional development goals and treaty obligations5 and conventions. This Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (CF), adopted by the BiH Council of Ministers at its 22nd Session on 16 December 2020 and reconfrmed by the BiH Presidency at its 114th Extraordinary Session on 5 March 2021, will guide the work of authorities in BiH and the UN system until 2025. This framework builds on the successes of our past cooperation and it represents a joint commitment to work in close partnership for results as defned in this Cooperation Framework that will help all people in BiH to live longer, healthier and more prosperous and secure lives. In signing hereafter, the cooperating partners endorse this Cooperation Framework and underscore their joint commitments toward the achievement of its results. Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina United Nations Country Team H.E. Dr. Zoran Tegeltija Dr. -

Central African Republic

Human Development Report 2014 Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience Explanatory note on the 2014 Human Development Report composite indices Central African Republic HDI values and rank changes in the 2014 Human Development Report Introduction The 2014 Human Development Report (HDR) presents the 2014 Human Development Index (HDI) (values and ranks) for 187 countries and UN-recognized territories, along with the Inequality-adjusted HDI for 145 countries, the Gender Development Index for 148 countries, the Gender Inequality Index for 149 countries, and the Multidimensional Poverty Index for 91 countries. Country rankings and values of the annual Human Development Index (HDI) are kept under strict embargo until the global launch and worldwide electronic release of the Human Development Report. It is misleading to compare values and rankings with those of previously published reports, because of revisions and updates of the underlying data and adjustments to goalposts. Readers are advised to assess progress in HDI values by referring to table 2 (‘Human Development Index Trends’) in the Statistical Annex of the report. Table 2 is based on consistent indicators, methodology and time-series data and thus shows real changes in values and ranks over time, reflecting the actual progress countries have made. Small changes in values should be interpreted with caution as they may not be statistically significant due to sampling variation. Generally speaking, changes at the level of the third decimal place in any of the composite indices are considered insignificant. Unless otherwise specified in the source, tables use data available to the HDRO as of 15 November 2013. -

Faqs) About the Gender Inequality Index (GII

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Gender Inequality Index (GII) What is the Gender Inequality Index? The Gender Inequality Index is a composite measure reflecting inequality in achievements between women and men in three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment and the labour market. It varies between zero (when women and men fare equally) and one (when men or women fare poorly compared to the other in all dimensions). The health dimension is measured by two indicators: maternal mortality ratio and the adolescent fertility rate. The empowerment dimension is also measured by two indicators: the share of parliamentary seats held by each sex and by secondary and higher education attainment levels. The labour dimension is measured by women’s participation in the work force. The Gender Inequality Index is designed to reveal the extent to which national achievements in these aspects of human development are eroded by gender inequality, and to provide empirical foundations for policy analysis and advocacy efforts. How is the GII calculated, and what are its main findings in terms of national and regional patterns of inequality? There is no country with perfect gender equality – hence all countries suffer some loss in their HDI achievement when gender inequality is taken into account, through use of the GII metric. The Gender Inequality Index is similar in method to the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) – see Technical Note 3 for details. It can be interpreted as a percentage loss to potential human development due to shortfalls in the dimensions included. Since the Gender Inequality Index includes different dimensions than the HDI, it cannot be interpreted as a loss in HDI itself. -

Human Development Index (HDI)

Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene Briefing note for countries on the 2020 Human Development Report Chile Introduction This year marks the 30th Anniversary of the first Human Development Report and of the introduction of the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI was published to steer discussions about development progress away from GPD towards a measure that genuinely “counts” for people’s lives. Introduced by the Human Development Report Office (HDRO) thirty years ago to provide a simple measure of human progress – built around people’s freedoms to live the lives they want to - the HDI has gained popularity with its simple yet comprehensive formula that assesses a population’s average longevity, education, and income. Over the years, however, there has been a growing interest in providing a more comprehensive set of measurements that capture other critical dimensions of human development. To respond to this call, new measures of aspects of human development were introduced to complement the HDI and capture some of the “missing dimensions” of development such as poverty, inequality and gender gaps. Since 2010, HDRO has published the Inequality-adjusted HDI, which adjusts a nation’s HDI value for inequality within each of its components (life expectancy, education and income) and the Multidimensional Poverty Index that measures people’s deprivations directly. Similarly, HDRO’s efforts to measure gender inequalities began in the 1995 Human Development Report on gender, and recent reports have included two indices on gender, one accounting for differences between men and women in the HDI dimensions, the other a composite of inequalities in empowerment and well-being. -

Gender and Education in UIS

BetweenBetween PromisePromise andand ProgressProgress EducationEducation andand GenderGender UNESCO Institute for Statistics BetweenBetween PromisePromise andand ProgressProgress The World Atlas on Gender Equality in Education comprises more than 120 maps, charts and tables featuring a wide range of sex‐disaggregated indicators produced by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics. It allows readers to visualize the educational pathways of girls and boys and track changes in gender disparities over time. 2 Two‐thirds of countries show gender parity in primary education Gender parity index in primary education 3 Out‐of‐school children, a continuing challenge for girls Percentage of female out‐of‐school children of primary age, by region and worldwide, 1990–2009 4 Boys tend to repeat grades more than girls Percentage of repeaters for selected countries, 2009 or latest year available 5 One‐third of countries have equal proportions of boys and girls enrolled in secondary education … Gender parity index in secondary education 6 … But many adolescent girls remain out of school in sub‐Saharan Africa, South and West Asia and the Arab States Rate of female out‐of‐ school adolescents 7 Women account for the majority of tertiary students in two‐thirds of countries… Gender parity index in tertiary education 8 … But men continue to dominate highest levels of study 56% of PhD graduates and 71% of researchers are men. 9 Women more present in Education, SS, Business and Law Education Eng, Man, Const % Fgraduates allfields Science SS, Bussi, Law 10 % M graduates -

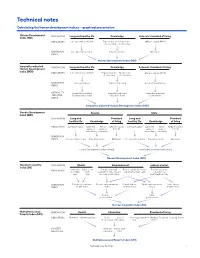

Technical Notes

Technical notes Calculating the human development indices—graphical presentation Human Development DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Index (HDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy index Education index GNI index INDEX Human Development Index (HDI) Inequality-adjusted DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Human Development Index (IHDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy Years of schooling Income/consumption INDEX INEQUALITY- Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted ADJUSTED life expectancy index education index income index INDEX Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) Gender Development Female Male Index (GDI) DIMENSIONS Long and Standard Long and Standard healthy life Knowledge of living healthy life Knowledge of living INDICATORS Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita years of years of (PPP $) years of years of (PPP $) schooling schooling schooling schooling DIMENSION INDEX Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Human Development Index (female) Human Development Index (male) Gender Development Index (GDI) Gender Inequality DIMENSIONS Health Empowerment Labour market Index (GII) INDICATORS Maternal Adolescent Female and male Female -

Inequalities in Human Development in the 21St Century

Human Development Report 2019 Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century Briefing note for countries on the 2019 Human Development Report Egypt Introduction The main premise of the human development approach is that expanding peoples’ freedoms is both the main aim of, and the principal means for sustainable development. If inequalities in human development persist and grow, the aspirations of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development will remain unfulfilled. But there are no pre-ordained paths. Gaps are narrowing in key dimensions of human development, while others are only now emerging. Policy choices determine inequality outcomes – as they do the evolution and impact of climate change or the direction of technology, both of which will shape inequalities over the next few decades. The future of inequalities in human development in the 21st century is, thus, in our hands. But we cannot be complacent. The climate crisis shows that the price of inaction compounds over time as it feeds further inequality, which, in turn, makes action more difficult. We are approaching a precipice beyond which it will be difficult to recover. While we do have a choice, we must exercise it now. Inequalities in human development hurt societies and weaken social cohesion and people’s trust in government, institutions and each other. They hurt economies, wastefully preventing people from reaching their full potential at work and in life. They make it harder for political decisions to reflect the aspirations of the whole society and to protect our planet, as the few pulling ahead flex their power to shape decisions primarily in their interests. -

Thresholds of Income Inequality That Mitigate the Role of Gender Inclusive Education in Promoting Gender Economic Inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Thresholds of income inequality that mitigate the role of gender inclusive education in promoting gender economic inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa Asongu, Simplice and Odhiambo, Nicholas January 2019 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/102033/ MPRA Paper No. 102033, posted 24 Jul 2020 14:05 UTC A G D I Working Paper WP/19/087 Thresholds of income inequality that mitigate the role of gender inclusive education in promoting gender economic inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa 1 Forthcoming: Social Responsibility Journal Simplice A. Asongu Department of Economics, University of South Africa. P. O. Box 392, UNISA 0003, Pretoria South Africa. E-mails: [email protected] , [email protected] Nicholas M. Odhiambo Department of Economics, University of South Africa. P. O. Box 392, UNISA 0003, Pretoria South Africa. E-mails: [email protected] , [email protected] 1 This working paper also appears in the Development Bank of Nigeria Working Paper Series. 1 2019 African Governance and Development Institute WP/19/087 Research Department Thresholds of income inequality that mitigate the role of gender inclusive education in promoting gender economic inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa Simplice A. Asongu & Nicholas M. Odhiambo January 2019 Abstract This study provides thresholds of inequality that should not be exceeded if gender inclusive education is to enhance gender inclusive formal economic participation in sub-Saharan Africa. The empirical evidence is based on the Generalised Method of Moments and data from 42 countries during the period 2004-2014. The following findings are established. First, inclusive tertiary education unconditionally promotes gender economic inclusion while the interaction between tertiary education and inequality is unfavourable to gender economic inclusion. -

Comparing Global Gender Inequality Indices: Where Is Trade?

DECEMB ER 2019 UNCTAD Research Paper No. 39 UNCTAD/SER.RP/2019/11 Nour Barnat Division on Comparing Global Gender Globalization and Development Strategies, UNCTAD Inequality Indices: Where is [email protected] Trade? Steve MacFeely Abstract Division on Globalization and This paper presents a comparative study of selected global Development gender inequality indices: The Global Gender Gap Index (GGI); Strategies, UNCTAD the Gender Inequality Index (GII); and the Social Institutions and [email protected] Gender Index (SIGI). A Principal Component Analysis approach is used to identify the most important factors or dimensions, such as, health, social conditions and education, economic and Anu Peltola labour participation and political empowerment that impact on gender and drive gender inequality. These factors are Division on Globalization and compared with the Sustainable Development Goal targets to Development assess how well they align. The findings show that while Strategies, UNCTAD economic participation and empowerment are significant [email protected] factors of gender equality, they are not fully incorporated into gender equality indices. In this context, the paper also discusses the absence of international trade, a key driver of economic development, from the gender equality measures and makes some tentative recommendations for how this lacuna might be addressed. Key words: Principal Component Analysis, Composite Indicators, 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, SDGs, Trade. © 2019 United Nations 2 UNCTAD Research Paper -

Gender Inequality Index and Related Indicators

TABLE 4 Gender Inequality Index and related indicators Population REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH with at least secondary Contraceptive prevalence Births Gender education Labour force participation rate rate, any At least attended Inequality Seats in (% ages 25 method one by skilled Index and older) (%) Maternal national (% of married antenatal health Total mortality Adolescent parliament women ages visit personnel fertility HDI rank Rank Value ratio fertility rate (% female) Female Male Female Male 15–49) (%) (%) rate 2011 2011 2008 2011a 2011 2010 2010 2009 2009 2005–2009b 2005–2009b 2005–2009b 2011a VERY HIGH HUMAN DEVELOPMENT 1 Norway 6 0.075 7 9.0 39.6 99.3 99.1 63.0 71.0 88.0 .. .. 2.0 2 Australia 18 0.136 8 16.5 28.3 95.1 97.2 58.4 72.2 71.0 100.0 100.0 2.0 3 Netherlands 2 0.052 9 5.1 37.8 86.3 89.2 59.5 72.9 69.0 .. 100.0 1.8 4 United States 47 0.299 24 41.2 16.8 c 95.3 94.5 58.4 71.9 73.0 .. 99.0 2.1 5 New Zealand 32 0.195 14 30.9 33.6 71.6 73.5 61.8 75.7 75.0 95.0 100.0 2.1 6 Canada 20 0.140 12 14.0 24.9 92.3 92.7 62.7 73.0 74.0 .. 98.0 1.7 7 Ireland 33 0.203 3 17.5 11.1 82.3 81.5 54.4 73.0 89.0 . -

Reducing Global Poverty Through Universal Primary and Secondary Education

Reducing global poverty through universal primary and secondary education POLICY PAPER 32 / Out-of-school children, adolescents FACT SHEET 44 and youth: global status and trends June 2017 FIGURE 1 The eradication of poverty and Global number of out-of-school children, adolescents and youth, 2000-2015 the provision of equitable and Primary age Lower secondary age Upper secondary age inclusive quality education for 400 World in 2000 all are two intricately linked 374.1 million 350 Sustainable Development 92.0 million Goals (SDGs). As this year’s 300 World in 2015 264.3 million High Level Political Forum 250 Female 83.5 million 68.7 million focuses on prosperity and 200 poverty reduction, this paper, 53.4 million Male 150 72.3 million jointly released by the UNESCO 45.1 million Female 29.8 million Institute for Statistics (UIS) 100 57.8 million Male 32.1 million and the Global Education 50 Female 32.4 million Out-of-school children, adolescents and youth 42.4 million Monitoring (GEM) Report, 0 Male 29.0 million shows why education is so 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 central to the achievement of Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics database. the SDGs and presents the latest estimates on out-of- school children, adolescents The number of children, adolescents and youth who are excluded from education fell steadily in and youth to demonstrate how the decade following 2000, but UIS data show that this progress essentially stopped in recent years; the total number of out-of-school children, adolescents and youth has remained nearly much is at stake. -

Malawi Systematic Country Diagnostic: Breaking the Cycle of Low Growth and Poverty Reduction

Report No. 132785 Public Disclosure Authorized Malawi Systematic Country Diagnostic: Breaking the Cycle of Low Growth and Slow Poverty Reduction December 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Malawi Country Team Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized i ABBREVIATION AND ACRONYMS ADMARC Agricultural Development and Marketing Corporation ANS Adjusted Net Savings APES Agricultural Production Estimates System BVIS Bwanje Valley Irrigation Scheme CDSSs Community Day Secondary Schools CBCCs community-based child care centers CPI Comparability of Consumer Price Index CCT Conditional cash transfers CEM Country Economic Memorandum DRM Disaster Risk Management ECD Early Childhood Development EASSy East Africa Submarine System IFPRI Food Policy Research Institute FPE Free Primary Education GPI Gender parity indexes GEI Global Entrepreneurship Index GDP Gross Domestic Product GER Gross enrollment rate GNI Gross national income IPPs Independent Power Producers IFMIS Integrated Financial Management Information System IHPS Integrated Household Panel Survey IHS Integrated Household Survey IRR internal rate of return IMP Investment Plan ECD Mainstream Early Childhood Development MACRA Malawi Communications Regulatory Authority MHRC Malawi Human Rights Commission SCTP Malawi’s Social Cash Transfer Program GNS Malawi's gross national savings MOAIWD Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development MPC Monetary Policy Committee MICS Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey NDRM National Disaster Risk Management NES National Export