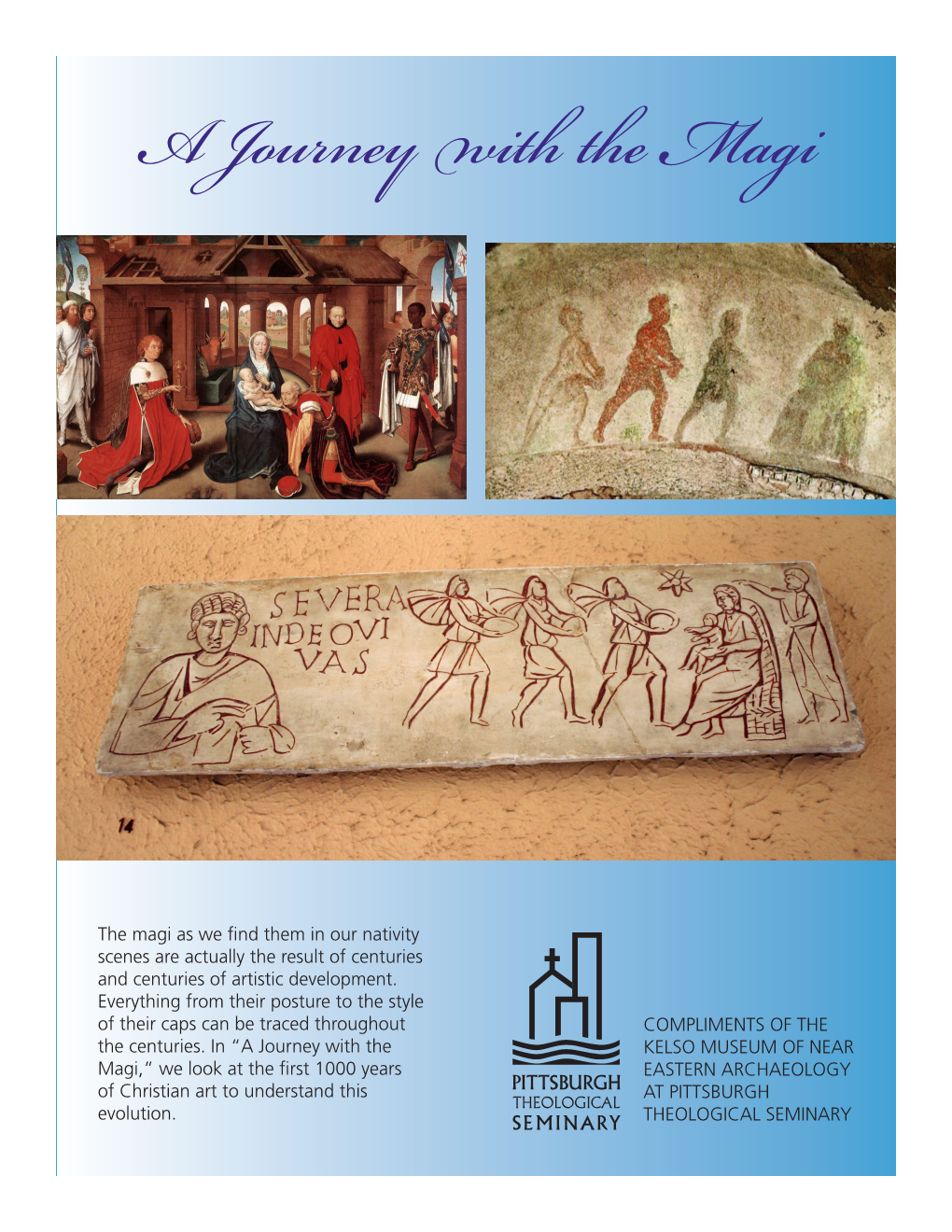

A Journey with the Magi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advent Morning Time Plans Cover

pambarnhill.com Your MorningBasket Morning Time Plans Christmas Celebration by Jessica Lawton Christmas Celebration Morning Time Plans Copyright © 2017 by Pam Barnhill All Rights Reserved The purchaser may print a copy of this work for their own personal use. Otherwise, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted without prior written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. For written permission contact [email protected]. Cover and design by Pam Barnhill. Christmas Celebration Morning Time Plans How to Use these plans Thanks so much for downloading our Christmas Celebration Morning Time plans. Our hope is that these plans will guide you as you do Morning Time with your family. While they can be followed to the letter, they are much better adapted to your family’s preferences and needs. Move subjects around, add your own special projects, or leave subjects out entirely. These are meant to be helpful, not stressful. The poems, prayer, and memorization sheets in this introductory section can be copied multiple times for your memory work binders. Feel free to print as many as you need. Companion Web Page For links to all the books, videos, resources, and tutorials in these plans, please visit: Christmas Celebration resource page. Choosing a Schedule We have included two different schedules for you to choose from. You can choose the regular weekly grid that schedules the subjects onto different days for you, or you can choose the loop schedule option. With the loop schedule you will do Prayer and Memorization daily. -

Art of Christmas: Puer Natus Est by Patrick Hunt

Art of Christmas: Puer Natus Est by Patrick Hunt Included in this preview: • Table of Contents • Preface • Introduction • Excerpt of chapter 1 For additional information on adopting this book for your class, please contact us at 800.200.3908 x501 or via e-mail at [email protected] Puer Natus Est Art of Christmas By Patrick Hunt Stanford University Bassim Hamadeh, Publisher Christopher Foster, Vice President Michael Simpson, Vice President of Acquisitions Jessica Knott, Managing Editor Stephen Milano, Creative Director Kevin Fahey, Cognella Marketing Program Manager Melissa Accornero, Acquisitions Editor Copyright © 2011 by University Readers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form or by any electronic, me- chanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, micro- filming, and recording, or in any information retrieval system without the written permission of University Readers, Inc. First published in the United States of America in 2011 by University Readers, Inc. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-60927-520-4 Contents Dedication vii Preface ix Introduction 1 Iconographic Formulae for Advent Art 9 List of Paintings 17 Section I: the annunciation 21 Pietro Cavallini 23 Duccio 25 Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi 27 Jacquemart -

Hans Memling's Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ And

Volume 5, Issue 1 (Winter 2013) Hans Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ and the Discourse of Revelation Sally Whitman Coleman Recommended Citation: Sally Whitman Coleman, “Hans Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ and the Discourse of Revelation,” JHNA 5:1 (Winter 2013), DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2013.5.1.1 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/hans-memlings-scenes-from-the-advent-and-triumph-of- christ-discourse-of-revelation/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This is a revised PDF that may contain different page numbers from the previous version. Use electronic searching to locate passages. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 5:1 (Winter 2013) 1 HANS MEMLING’S SCENES FROM THE ADVENT AND TRIUMPH OF CHRIST AND THE DISCOURSE OF REVELATION Sally Whitman Coleman Hans Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ (ca. 1480, Alte Pinakothek, Munich) has one of the most complex narrative structures found in painting from the fifteenth century. It is also one of the earliest panoramic landscape paintings in existence. This Simultanbild has perplexed art historians for many years. The key to understanding Memling’s narrative structure is a consideration of the audience that experienced the painting four different times over the course of a year while participating in the major Church festivals. -

Teaching Support Sheet Presenter: Leah R

Open Arts Objects http://www.openartsarchive.org/open-arts-objects Teaching Support Sheet presenter: Leah R. Clark work: Andrea Mantegna, Adoration of the Magi, c. 1495-1505, 48.6 x 65.6 cm, distemper on linen, The Getty Museum, Los Angeles In this short film, Dr Leah Clark discusses the global dimensions of a painting by the Renaissance court artist Andrea Mantegna. There are a variety of activities to get students thinking about close-looking around a Renaissance painting. There are also different themes that you can use to tease out some of the main issues the film raises: visual analysis of a painting; the Italian Renaissance’s relationship to the larger world; collecting practices in the Renaissance; diplomacy and gift giving; cross-cultural exchanges; devotional paintings; the court artist. http://www.openartsarchive.org/resource/open-arts-object-mantegna-adoration-magi-c-1495-1505-getty- museum-la Before watching the film Before watching the film, locate the work online and download an image of the work here that you can use to show to your class. The Getty provides a very high resolution image, where you can zoom in closely to view the details: http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/781/andrea-mantegna-adoration-of-the- magi-italian-about-1495-1505/ Questions to ask your students before watching the film. 1. What do you know of the Renaissance as a time period? 2. What do you think the painting depicts? Can you identify any recognisable elements? 3. In what location do you think the painting is taking place? Why? What do you think the three people on the right are holding? 4. -

Adoration of the Magi Stained Glass Art

Adoration of the Magi Stained Glass Art The Adoration of the Magi in Stained Glass A favorite subject of Christian stained glass art, the Adoration of the Magi commemorates the birth of Jesus and His worship as the King. In keeping with the theme of the Nativity, the Adoration of the Magi maintains the soft intimacy of reverence and joy expressed in the demeanor of the Three Magi and all who observe the blessed event. The eastern star is prominently displayed in most of the Stained Glass Inc. Panel 1071: Rose Nativity selections, along with a variety of iconographic images that include the Cross and The Lamb. These stained glass window inserts are sure to inspire heightened Stained Glass Inc., Greenville, TX. contemplative worship wherever they are placed. The Story of the Adoration With direct scriptural reference in Matthew 2:1-11, the Holy Bible provides a foundation for the birth of Jesus as the King with the story of the arrival of the Three Magi. Travelling a great distance from the east with gifts of frankincense, gold and myrrh, the Three Magi follow a brilliant star that [email protected] www.StainedGlassInc.com leads them to the humble manger where Jesus lay with Mary and Joseph. When the Magi initially arrive in Jerusalem, however, they inquire of the local people regarding their knowledge of where the infant Jesus might be found. News of their quest quickly travels to the ears of Herod the King. Calling the Three Magi in secret to come and speak with him about their visit, Herod asked the Three Magi to report back to him as soon as they find the baby. -

The Magi and the Manger: Imaging Christmas in Ancient Art and Ritual

The Magi and the Manger: Imaging Christmas in Ancient Art and Ritual By Felicity Harley-McGowan and Andrew McGowan | Volume 3.1 Fall 2016 The story of the birth of Jesus Christ is familiar, both from the biblical narratives and from iconography that has become ubiquitous in church decoration and widely circulated on Christmas cards: a mother and father adoring their new-born child, an ox and an ass leaning over the child, a star hovering above this scene, angels, shepherds with their sheep in a field, and luxuriously clad “wise” men or kings approaching the child with gifts. All these elements are included by the Venetian artist Jacopo Tintoretto in a painting which started in his workshop in the late 1550s, and for much of its life hung above the altar of a church in Northern Italy (Fig. 1). In addition, Tintoretto imagines other figures at the scene. With Mary and Joseph at the manger, he includes a second pair of human figures, perhaps the parents of the Virgin: Anna and Joachim. The artist also inserts less traditional animals in the foreground: a chicken and a rabbit, and a dog curled at the foot of the manger. Fig. 1. Jacopo Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti), The Nativity, Italian, late 1550s (reworked, 1570s), oil on canvas, 155.6 x 358.1 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: gift of Quincy Shaw, accession number 46.1430. Photograph © 2016 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Yet the rich details of the scene that Tintoretto depicts, many of which are now well known in popular renditions, were not present in the first depictions of the Nativity. -

Telling Stories “When They Saw the Star, They Were Overjoyed

Fra Angelico and Fra Filippo Lippi Fra Angelico and Fra Filippo Lippi, The Adoration of the Magi, c. 1440 / 1460, tempera on panel, National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection A Long Journey 1 As told in the Gospels of the New Testament, the life of Florence, Italy, in the fifteenth century. The journey of Jesus began with his extraordinary yet humble birth in the three wise men was often depicted in Florentine art Bethlehem. Shepherds and three Magi (wise men from and reenacted in Epiphany processions through the city. the East) visited the manger where Jesus was born to In Renaissance Italy, religious images, from large altar- pay their respects. The Adoration of the Magi depicts the pieces for churches to small paintings for private devo- moment when the three wise men, bringing gifts of tion in homes, were the mainstay of artists’ workshops. gold, frankincense, and myhrr, kneel before the infant. At the time, not all common people could read. Stories The story of the Magi was particularly popular in from the Bible were reproduced in paintings filled with symbols that viewers could easily understand. 70 Telling Stories “When they saw the star, they were overjoyed. On coming to the house, they saw the child with his mother Mary, and they bowed down and worshiped him. Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of gold and of incense and of myrrh.” Matthew 2:10 – 11 Look Around 2 The Adoration of the Magi is one of the first examples of a tondo (Italian for “round painting”), a popular form for religious paintings in the 1400s. -

El Greco the Next Painting Is by a Famous Artist Called “El Greco” Which Is Spanish for “The Greek” A

1 The Art of Christmas Teacher’s Guide Students: May be modified for any grade. Advanced Study is for grades 6 and up. Materials: Seven versions of “Adoration of the Christ Child.” Instructional Goals: After the lesson, the student shall be able to: State why paintings were so important for thousands of years; State at least three groups of people who used paintings to communicate ideas; Select the name of the artist who most revolutionized painting; Select the period (years) of his works; Name at least three ways that he showed other artists to improve their paintings; When shown a series of paintings, the student shall be able to identify those painted before Caravaggio and those that were painted after; 2 Lesson Plan – Before Visiting Gallery Background: Before going to the gallery to view the paintings, students should be fluent with the following facts: 1. For thousands of years, paintings were the main way of communicating. A. Movies, television, and photographs are all very recent inventions. The first cameras in general use appeared only 150 years ago, movies appeared about 80 years ago and television began about 50 years ago. B. So for most of history - for thousands and thousands of years – pictures had to be hand- painted by an artist to communicate ideas, tell stories and help teach moral traditions. C. Also for most of history, most people could not read or get books. D. Therefore painted pictures were one of the only ways of passing along information because most people could not read and there was no TV or Internet. -

The Adoration of the Magi

The Adoration of the Magi Gentile da Fabriano (c. 1370 – c. 1427) The Adoration of the Magi This talk is based on two (2) articles / reflections in the The Sower magazine (October – December 2007) by Lionel Gracey and and Caroline Farey. The Adoration of the Magi Gentile da Fabriano (c. 1370 – c. 1427) was an Italian painter known for his participation in the International Gothic style. Gentile was born in or near Fabriano, in the Marche. His mother died some time before 1380 and his father, Niccolò di Giovanni Massi, retired to a monastery in the same year, where he died in 1385. He worked in various places in central Italy, mostly in Tuscany. His best known works are his Adoration of the Magi (1423) and Flight into Egypt. The Adoration of the Magi About 1422 he went to Florence, where in 1423 he painted an "Adoration of the Magi" as an altarpiece for the church of Santa Trinita, which is now preserved in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. This painting is considered his best work now extant and regarded as one of the masterpieces of the International Gothic style. He had by this time attained a wide reputation, and was engaged to paint pictures for various churches, more particularly Siena, Perugia, Gubbio and Fabriano. The Adoration of the Magi About 1426 he was called to Rome by Pope Martin V to adorn the church of St. John Lateran with frescoes from the life of John the Baptist. He also executed a portrait of the pope attended by ten cardinals, and in the church of St. -

Jean Gossart the Adoration of the Kings Lorne Campbell

JEAN GOSSART THE ADORATION OF THE KINGS LORNE CAMPBELL From National Gallery Catalogues: The Sixteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings with French Paintings before 1600 © National Gallery Company Limited ISBN 9 781 85709 370 4 Published online 2011; publication in print forthcoming www.nationalgallery.org.uk Lorne Campbell Jan Gossaert (Jean Gossart) The Sixteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings NG2790 The Adoration of the Kings with French Paintings before 1600 SIGNATURES AND INSCRIPTIONS Jan Gossaert (Jean Gossart) NG2790 The Adoration of the Kings Oil on oak panel, 179.8 x 163.2 cm, painted surface approximately 177.2 x 161.8 cm Signatures NG2790 is signed in two places: once on the collar of the black king’s black attendant, IENNIN GOSS... ; a second time on the black king’s hat, IENNI/ GOSSART: DEMABV... (the A in GOSSART is unlike the other A; the reason is not obvious). Inscriptions On the black king’s hat: BALTAZAR. Near the hem of the scarf held by the black king: SALV[E]/ REGINA/ MIS[ERICORDIAE]/ V:IT[A DULCEDO ET SPES NOSTRA] (Hail, Queen of Mercy, our life, our sweetness and our hope). On the scroll held by the second angel from the left: Gloria:in:excelcis:deo: (Glory to God in the highest). On the object at the Virgin’s feet, which is the lid of the chalice presented by the eldest king: [L]E ROII IASPAR (the king Caspar). © National Gallery Company Limited Lorne Campbell Jan Gossaert (Jean Gossart) The Sixteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings NG2790 The Adoration of the Kings with French Paintings before 1600 PROVENANCE No reference to NG2790 has been found before 1600, when it was in a chapel dedicated to the Virgin in the church of the Benedictine Abbey of Geraardsbergen (Grammont) in East Flanders, south of Ghent and west of Brussels. -

THE FLIGHT INTO EGYPT Sunday After Christmas STEPHEN the PROTOMARTYR

THE FLIGHT INTO EGYPT Sunday After Christmas STEPHEN the PROTOMARTYR December 27, 2009 Revision E GOSPEL: Matthew 2:13-23 EPISTLE: Galatians 1:11-19 This Gospel lesson for Christmas Day in the East is the visit of the Magi, which is used universally in the West for Epiphany. The Gospel for the Sunday after Christmas in the East is the Flight into Egypt, which is used by some Churches in the West for the Sunday after New Year’s Day. Table of Contents Review of the Visit by the Magi ............................................................................................................... 423 The Visit of the Magi ........................................................................................................................... 424 Who Were the Magi? ...................................................................................................................... 424 The Star That the Magi Followed ................................................................................................... 424 The Gifts That the Magi Brought ................................................................................................... 425 How Much Did the Magi Know? ................................................................................................... 426 What Did the Magi Learn from the Star? .................................................................................. 427 What Induced the Magi to Visit a King in a Far-Away Country? ............................................. 428 Why Did Herod and the Jews -

The Nativity in Art the Shepherds’ and Magi’S Adoration of the Christ Child Are Key Elements of the Larger Nativity Cycle, the Story of the Birth of Jesus

The Nativity in Art The shepherds’ and Magi’s adoration of the Christ Child are key elements of the larger nativity cycle, the story of the birth of Jesus. How does the traditional iconography used to depict these two stories in art reveal the theological depths of the Nativity? Christian Reflection Prayer A Series in Faith and Ethics Scripture Reading: Luke 2:1-20 Reflection When we hear Luke’s story of Christ’s birth, how can we “resist being swept back into a sentimental stupor recalling Christmas days of past childhood?” Heidi Hornik and Mikeal Parsons ask. For Focus Articles: Luke’s original auditors, however, the story’s setting and characters The Shepherds’ Adoration were wild and unsavory, associated with danger. The angels’ (Christmas and Epiphany, message of peace was proclaimed not over a quaint scene, but to pp. 34-40) violent people working in a countryside known as a haven for vagabonds and thieves. In the shepherds’ rush to the Manger and The Magi’s Adoration their return “glorifying and praising God,” we see the Messiah’s (Christmas and Epiphany, power to lift up the lowly, despised, and violent. pp. 32-33) But the shepherds were not the only group to adore the Christ child. The Magi—wise men, or astrologers, who were very different from the shepherds—were also summoned to Bethlehem (Matthew 2:1-12). Their story, when put beside the Lukan account of the shepherds, emphasizes the radical inclusivity of Christ. Both the lowly, menial shepherds and the sophisticated, scholarly Magi were welcomed at the Manger to worship.