Mudgee Dolomite & Lime Pty Ltd V Robert Francis Murdoch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mudgee and Gulgong Urban Release Strategy

Mudgee and Gulgong Urban Release Strategy Prepared for Mid-Western Regional Council December 14 Mudgee and Gulgong Urban Release Strategy QUALITY ASSURANCE Report Contacts LOUISE BOCHNER BSc (Macquarie), M. Urban & Regional Planning (USYD), MPIA Senior Consultant [email protected] Quality Control This document is for discussion purposes only unless signed and dated by a Principal of HillPDA. Reviewed by: ……………………………………………….. Dated: 18 December 2014 DAVID PARSELL M. Public Administration (USYD), M. Environmental Planning (Macquarie), B. Commerce (UTAS) Principal Planner and Practice Manager [email protected] Report Details Job Ref No: C14185 Version: Final Date Printed: 18/12/2014 Ref: C14185 HillPDA Page 2 | 113 Mudgee and Gulgong Urban Release Strategy CONTENTS Executive Summary .............................................................................. 7 1 Introduction ................................................................................. 21 Purpose of the Strategy ............................................................... 21 Strategy timeframe and Review .................................................. 21 Strategy Area ............................................................................... 21 Strategy Methodology ................................................................. 25 Land Supply Monitor ................................................................... 26 2 Demographic Trends ................................................................... 27 Population................................................................................... -

A Review of the Unique Features of the Orange Wine Region NSW - Australia

Terroir 2010 A review of the unique features of the Orange wine region NSW - Australia Orange Region Vignerons Association Photo: Courtesy of Angullong Wines Euchareena ORANGE WINE Region ver Ilford Ri ll Be Kerrs Hill Creek End Molong Ca Turo pertee n Ri River Ma ver Garra c Sofala qu Mullion a ri e Parkes Creek Ri ve Ophir r Cookamidgera Manildra Clergate March Borenore Lewis Ponds Cudal Nashdale ORANGE Cullen Toogong Lucknow Peel Bullen Mt Canobolas Portland Cargo Spring BATHURST Wallerawang Cumbijowa Eugowra Vittoria Cadia Hill L a Millthorpe ch Yetholme lan R Panuara ive Perthville Lithgow r Blayney O’Connell Canowindra Hartley Newbridge Fish River Gooloogong Belubula River Carcoar Barry Hampton Lyndhurst Mandurama Co r xs Projection: UTM MGA Zone 55. Scale 1:1,250,000. Rockley ve Ri Ri s Neville ll ver This map incorporates data which is © Commonwealth of be Australia (Geoscience Australia), 2008, and which is © p Woodstock am Oberon Crown Copyright NSW Land and Property Management C Authority, Bathurst, Australia, 2010. All rights reserved. Trunkey Produced by the Resource Information Unit, Industry & Edith Investment NSW, August 2010. Cowra Creek Figure 1. The Orange wine region in NSW. Source: NSW Department of Industry & Investment ORANGE WINE Region Euchareena ver Ilford Ri The Orange wine region was accepted as a distinct Geographic Area (GI) by ll Be Kerrs Hill the Australian Wine & Brandy Corporation in 1997. The Orange wine region is Creek End Molong Ca Turo pertee n Ri River Ma ver defined as the contiguous (continuous) land above 600m elevation in the Shires Garra c Sofala qu Mullion a ri e Parkes Creek Ri of Cabonne, Blayney and Orange City. -

Cycle Mudgee Region

CYCLE MUDGEE REGION TOURIST INFORMATION MUDGEE REGIONAL MAP This booklet has been produced in Mudgee Visitor Information Centre response to the increasing number of 84 Market Street, Mudgee 2850 cyclists visiting the Mudgee region who Ph: (02)6372 1020 Fax: (02)6372 2853 enquire about "good places to ride". Email: [email protected] Web: www.visitmudgeeregion.com.au It also aims to encourage residents to Open: 9.00am–5.00pm, 7 days a week explore and enjoy their local area by bicycle. A group of local, experienced cyclists Gulgong Visitor Information Centre have selected 20 rides, with a good 109 Herbert Street, Gulgong 2852 cross-section of grade and distance, Ph: (02)6374 1202 Fax: (02)6374 2229 one or more of which will suit the ability Open: Monday to Friday 8am-5.00pm of most cyclists. (Closed 1.00pm–1.30pm on weekdays) Saturday 9.30am-3pm In compiling the many routes for this Sundays & Public Holidays 9.30-2pm booklet, an attempt was made to avoid busy roads where possible, so that cyclists could experience the many Rylstone Visitor Information Centre quieter, pleasant country back roads in 77 Louee Street, Rylstone. this region. Ph: (02) 6379 0100 Lastly, there are a number of wonderful Open: Monday – Friday 8am – 4.30pm venues worth visiting along some of (closed 1pm – 1.30pm on weekdays) these rides - wineries, cafes, galleries - Weekends: @ Lakelands Tasting so please check with the Visitor Room, cnr Louee & Cudgegong Sts, Information Centre for their opening Rylstone. Ph: (02) 6379 0790. times. Open: Saturday, Sunday & public holi- March 2008 days 10.00am – 4.00pm ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This booklet was compiled by various local riders and funded by Mid-Western Regional Council. -

APPENDIX 6 – COMMUNITY 2017 Annual Review – Wilpinjong Coal Mine Appendix 6 - Community

APPENDIX 6 – COMMUNITY 2017 Annual Review – Wilpinjong Coal Mine Appendix 6 - Community Community Complaints for the 2017 Review Period Date and Time From Concern Raised Received Investigation and Action Taken 13 Jan 2016 at Wollar Village (no fixed Noise Telephone Complaints Caller reported hearing noise from Wilpinjong Coal (WC). WC staff confirmed that the real-time 8:25 AM address) Line low frequency (LF) noise levels recorded at Wollar Village were compliant at that time. WC staff spoke to the Caller by phone. 14 Jan 2017 at Mogo Road, Wollar Noise Telephone Complaints Caller reported hearing noise from WC. WC staff spoke to the Caller by phone. WC staff 9:44 AM Line investigated call and determined that low frequency (LF) noise levels recorded at Araluen Road (closest noise monitor to Caller) were compliant. 18 Jan 2017 at Mogo Road, Wollar Noise Telephone Complaints Caller reported hearing ‘excessive’ noise from WC. WC staff spoke to the Caller by phone. WC 11:34 PM Line staff investigated call and determined that low frequency (LF) noise levels recorded at Araluen Road (closest noise monitor to Caller) were compliant. 19 Jan 2017 at Mogo Road, Wollar Noise Telephone Complaints Caller reported hearing ‘excessive’ noise from WC. WC staff spoke to the Caller by phone. WC 9:11 AM Line staff investigated call and determined that low frequency (LF) noise levels recorded at Araluen Road (closest noise monitor to Caller) were compliant. 19 Jan 2017 at Mogo Road, Wollar Noise & Blast Telephone Complaints Caller reported hearing noise and a blast from WC. WC staff spoke to the Caller by phone. -

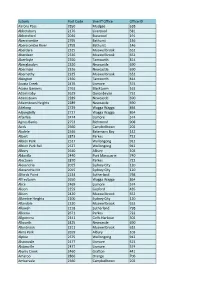

Suburb Post Code Sheriff Office Office ID Aarons Pass 2850 Mudgee 638

Suburb Post Code Sheriff Office Office ID Aarons Pass 2850 Mudgee 638 Abbotsbury 2176 Liverpool 581 Abbotsford 2046 Burwood 191 Abercrombie 2795 Bathurst 146 Abercrombie River 2795 Bathurst 146 Aberdare 2325 Muswellbrook 652 Aberdeen 2336 Muswellbrook 652 Aberfoyle 2350 Tamworth 814 Aberglasslyn 2320 Newcastle 690 Abermain 2326 Newcastle 690 Abernethy 2325 Muswellbrook 652 Abington 2350 Tamworth 814 Acacia Creek 2476 Lismore 574 Acacia Gardens 2763 Blacktown 163 Adaminaby 2629 Queanbeyan 752 Adamstown 2289 Newcastle 690 Adamstown Heights 2289 Newcastle 690 Adelong 2729 Wagga Wagga 864 Adjungbilly 2727 Wagga Wagga 864 Afterlee 2474 Lismore 574 Agnes Banks 2753 Richmond 908 Airds 2560 Campbelltown 202 Akolele 2546 Batemans Bay 142 Albert 2873 Parkes 722 Albion Park 2527 Wollongong 912 Albion Park Rail 2527 Wollongong 912 Albury 2640 Albury 103 Aldavilla 2440 Port Macquarie 740 Alectown 2870 Parkes 722 Alexandria 2015 Sydney City 120 Alexandria Mc 2015 Sydney City 120 Alfords Point 2234 Sutherland 798 Alfredtown 2650 Wagga Wagga 864 Alice 2469 Lismore 574 Alison 2259 Gosford 435 Alison 2420 Muswellbrook 652 Allambie Heights 2100 Sydney City 120 Allandale 2320 Muswellbrook 652 Allawah 2218 Sutherland 798 Alleena 2671 Parkes 722 Allgomera 2441 Coffs Harbour 302 Allworth 2425 Newcastle 690 Allynbrook 2311 Muswellbrook 652 Alma Park 2659 Albury 103 Alpine 2575 Wollongong 912 Alstonvale 2477 Lismore 574 Alstonville 2477 Lismore 574 Alumy Creek 2460 Grafton 441 Amaroo 2866 Orange 706 Ambarvale 2560 Campbelltown 202 Amosfield 4380 Tamworth 814 Anabranch -

APPENDIX 4 Flora, Fauna, Aquatic

Moolarben Coal Project Stage 1 Modification (MOD 4) APPENDIX 4 Flora, Fauna, Aquatic Ecological Impact Assessment – Moolarben Coal Project Ulan Ecological Impact Assessment Proposed rail line loop Moolarben Coal Project Ulan Wollar Road, Ulan 7 April 2009 Prepared and Printed by: Prepared for: Ecovision Consulting Moolarben Coal Operations Pty Limited PO Box 650 Charlestown NSW 2290 C/ Wells Environmental Services TEL.FAX +61 (02) 4942 6404 PO Box 205 Maitland NSW 2323 ABN: 99 106 911 273 Distribution: File Name: 2009_2002_FF_28Mar09 Copies supplied to intended recipient: 4 © Trimark Developments Pty Limited Copies retained by Ecovision Consulting: 1 This document is copyright. Apart from any fair dealings associated with the specified project, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the express permission of Ecovision Consulting (Trimark Developments Pty Limited). No warranty is placed on the content of this report where it can be demonstrated that amendments to relevant legislation, regulation and/or guidelines have occurred subsequent to the published date of this report. Signature: Date: 7 April 2009 Mark Aitkens BSc (Env. Biol.) Principal – Ecovision Consulting 2009_2002_FF_28Mar09 ii Ecological Impact Assessment – Moolarben Coal Project Ulan Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The Project .......................................................................................................................................... -

Peabody Wilpinjong Coal Social Impact Management Plan

PEABODY WILPINJONG COAL SOCIAL IMPACT MANAGEMENT PLAN WI-ENV-MNP-0047 September 2019 Document Owner Document Approver Environmental Advisor Environment and Community Manager Version Approval Date Approver Name 1 - Document Version Date Prepared by Distribution Description of Change No. WCM CCC Draft for MWRC WI-ENV-MNP- Elliott Whiteing stakeholder April 2018 SSD-6764 0047 Pty. Ltd Registered consultation Aboriginal Parties Publicly SIMP for available WI-ENV-MNP- Elliott Whiteing submission to September 2018 following SSD-6764 0047 Pty. Ltd DP&E DP&E Approval Publicly SIMP update to available WI-ENV-MNP- Elliott Whiteing address DPIE September 2019 following SSD-6764 0047 Pty. Ltd comments. DPIE Approval Wilpinjong Coal – Social Impact Management Plan Document Number: WI-ENV-MNP-0047 Uncontrolled when printed 2 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Purpose 5 1.2 SIMP methodology 8 1.3 Stakeholder engagement 8 2 Statutory Requirements 10 2.1 Conditions of Approval 10 2.2 Voluntary Planning Agreement 11 2.3 SIA Guideline 12 2.4 Government Planning and Policy Directions 12 3 Social Impacts, Opportunities and Significance 14 3.1 Issues raised in Draft SIMP consultation 14 3.2 Update to Social Impacts and Benefits 17 3.2.1 Local level 17 3.2.2 Regional level 18 3.3 Mine Closure and Decommissioning 19 3.3.1 Loss of employment and supply arrangements 19 3.3.2 Village of Wollar 20 3.3.3 Cumulative impacts associated with decommissioning and closure 21 4 Social Impact Management Measures 22 4.1 Village of Wollar 22 4.1.1 Mitigation upon request 23 4.1.2 -

Our Place 2040 Mid-Western Regional Local Strategic Planning Statement

OUR PLACE 2040 MID-WESTERN REGIONAL LOCAL STRATEGIC PLANNING STATEMENT MAY 2020 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 1.1 About this Local Strategic Planning Statement 3 1.2 Policy Context 3 1.3 Purpose of this Local Strategic Planning Statement 3 1.4 Consultation 3 2. Context 4 2.1 Our Place in the Central West and Orana Region 4 2.2 Our Community 6 2.3 Our Local Advantages 8 2.4 Our Local Opportunities 8 3. Land Use Vision 10 4. Our Themes & Planning Priorities 11 4.1 Planning Priorities 11 4.2 Actions 11 4.3 Structure Plans 11 5. Implementation, Monitoring and Reporting 35 6. References 39 7. Glossary 40 OUR PLACE 2040 – MID-WESTERN REGIONAL LOCAL STRATEGIC PLANNING STATEMENT | MAY 2020 2 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 About this Local Strategic 1.4 Consultation Planning Statement The LSPS has been informed by the results The Mid-Western Regional Local Strategic of community engagement undertaken Planning Statement (LSPS) sets out the 20 in developing the Mid-Western Region year vision for land use planning in the Mid- Community Plan Towards 2030 and recent Western Regional Council local government surveys completed by the community with a area (Region). specific focus on Land Use in the Region. The LSPS outlines land use Planning Priorities Council developed five surveys to capture and sets short, medium and long term community input on Land Use Vision, actions to deliver the Planning Priorities for Growth, Town Centres, Design Considerations the community. and Tourism. 286 responses were received and have helped inform the preparation of The LSPS also outlines the means for the LSPS. -

Cox of Mulgoa and Mudgee 1

Cox of Mulgoa and Mudgee INTRODUCTION The Cox family is one of considerable historical importance in both Mulgoa and Mudgee, for they pioneered both districts and contributed much to their development. George Cox, along with his brothers Henry and Edward, established noted Mulgoa district estates: George was at Winbourne, Henry at Glenmore and Edward at Fernhill. They were the sons of Lieutenant William Cox who constructed the first road from Emu Plains over the Blue Mountains to Bathurst in 1814œ1815; all four men played significant roles in settling the Bathurst, Mudgee and Rylstone districts, albeit as absentee landlords. George Cox's Winbourne estate and mansion in particular played a significant role in the agricultural and social life of the Mulgoa district in the nineteenth century. GEORGE COX George Cox was born on 18 February 1795 at Devizes, Wiltshire, the fourth son of William Cox and Rebecca, nee Upjohn. William Cox, born at Wimbourne Minster, Dorset, England, 19 December 1764, became a Lieutenant in the NSW Corps and arrived in Sydney on 11 January 1800 per Minerva, accompanied by his wife and four of their sons: James, aged 10; Charles, 7; George, 5²; and Henry, 4. After an unsuccessful start at Brush Farm at Pennant Hills, the Cox family settled at Clarendon, Windsor, in 1804. William and his sons became interested in land in the Mulgoa district, and in 1810 Edward, at the age of four, received the first grant in the area, of 300 acres, which ultimately became Fernhill. George Cox's grant of 600 acres, the future site of Winbourne, spelt originally without the 'e', was made on 8 October 1816. -

Habitat Linkages: Bellevue Estate

Local Government Taking Action to Protect Ecosystems 2016/17 Central Tablelands Local Land Services Incentive Funding Yellow-billed Spoonbill & Black-winged Stilt Restoration of Detention Basins to Provide Habitat Linkages ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES Habitat Linkages: Bellevue Estate Mid-Western Regional Council There are three detention basins events and release the captured Urbanisation along White Circle in Bellevue stormwater to downstream Ever expanding urban areas mean Estate, Mudgee, as well as an receiving waters in a more that natural waterways are often additional basin off Rifle Range controlled manner. negatively altered having impacts Road which are all part of a Detention basins are primarily on water quality and habitat major catchment feeding into the designed as a flood mitigation tool values. Stormwater typically Cudgegong River. and typically remain as dry, grassed travels at high velocities and These detention basins are barren basins outside of rain events. By collects pollutants from roads, grassed landscapes that currently collecting and slowing the flow of roofs and other hard surfaces. provide little to no amenity value stormwater, these basins act to or environmental benefit. This direct water to creeks and rivers at project will result in planting of the a slower, more natural rate thereby detention basins and associated minimising erosion and flooding of drainage reserves with native waterways. vegetation to create valuable Improving Habitat habitat and linkages for native fauna. As well as planting these existing detention basins with native Plant species will include those vegetation, wetland areas will be known to be critical habitat for a Habitat Creation constructed within the base of the number of threatened bird species By utilising existing detention detention basins. -

Values of the Metropolitan Rural Area of the Greater Sydney Region

Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................. 5 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 14 1.1 Metropolitan Rural Areas .............................................................................................................................................................. 14 1.2 Policies Relating to Agriculture in the MRA .......................................................................................................................... 15 1.3 A Plan for Growing Sydney .......................................................................................................................................................... 16 1.4 Greater Sydney Commission and District Plans .................................................................................................................. 17 1.5 This Report .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 2 Introduction to Economic, Social and Environmental Values of the MRA ................................................. 19 3 Determinants of Economic, Environmental and Social Value of the MRA ................................................. 21 4 Agriculture Values of the MRA ........................................................................................................................ -

The June Edition Central Tablelands Telegraph

Welcome to the June Edition Central Tablelands Telegraph Inside this edition. 1. Meet the Board 2. Across the Central Tablelands 3. In the News 4. What are we currently working on? 5. What's happening around the traps? 6. The funding arena 7. Find your local office 8. Give us your feedback 9. Find us online Meet the Central Tablelands LLS Board The Board of Central Tablelands Local Land Services met in Orange earlier this month to discuss the many issues facing ratepayers, landholders and communities at present. It was the perfect opportunity for us to capture a photo of them together and introduce them. Pictured above are John Lowe, Ian Armstong (Chair), Pip Job, Reg Kidd, Ian Rogan, Peter Sparkes (General Manager) and John Seaman. Bruce Gordon was absent when the image was taken. In Focus - Central Tablelands Board Member Pip Job Passionate about agriculture and in particular, the need for agriculture and natural resource management to be integrated to create a sustainable future for generations to come, Pip has dedicated her time to make this passion a reality. As CEO of the Little River Landcare Group at Yeoval, she specialises in agricultural and natural resource management education and project delivery. Chair of the Central West NRM Working Group and an executive committee member of Landcare NSW Inc, Pip also holds an Advanced Diploma in Agriculture, a Diploma in Community Coordination and Facilitation and a Diploma in Holistic Management. A beef cattle breeder who uses the principles of managing holistically to improve the environment, generate profit and create opportunities for her family and community, Pip also holds the position of secretary of the NSW Shorthorn Ladies branch and Chief Steward of the Cumnock Show Cattle section.