1. the Introduction to Detournement As Pedagogical Praxis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cosmonauts of the Future: Texts from the Situationist

COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Texts from The Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen 1 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE 2 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Texts from the Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere 3 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE TEXTS FROM THE SITUATIONIST MOVEMENT IN SCANDINAVIA AND ELSEWHERE Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Published 2015 by Nebula in association with Autonomedia Nebula Autonomedia TEXTS FROM THE SITUATIONIST Læssøegade 3,4 PO Box 568, Williamsburgh Station DK-2200 Copenhagen Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Denmark USA MOVEMENT IN SCANDINAVIA www.nebulabooks.dk www.autonomedia.org [email protected] [email protected] AND ELSEWHERE Tel/Fax: 718-963-2603 ISBN 978-87-993651-8-0 ISBN 978-1-57027-304-9 Edited by Editors: Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen | Translators: Peter Shield, James Manley, Anja Büchele, Matthew Hyland, Fabian Tompsett, Jakob Jakobsen | Copyeditor: Marina Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen Vishmidt | Proofreading: Danny Hayward | Design: Åse Eg |Printed by: Naryana Press in 1,200 copies & Jakob Jakobsen Thanks to: Jacqueline de Jong, Lis Zwick, Ulla Borchenius, Fabian Tompsett, Howard Slater, Peter Shield, James Manley, Anja Büchele, Matthew Hyland, Danny Hayward, Marina Vishmidt, Stevphen Shukaitis, Jim Fleming, Mathias Kokholm, Lukas Haberkorn, Keith Towndrow, Åse Eg and Infopool (www.scansitu.antipool.org.uk) All texts by Jorn are © Donation Jorn, Silkeborg Asger Jorn: “Luck and Change”, “The Natural Order” and “Value and Economy”. Reprinted by permission of the publishers from The Natural Order and Other Texts translated by Peter Shield (Farnham: Ashgate, 2002), pp. 9-46, 121-146, 235-245, 248-263. -

The Interventions of the Situationist International and Gordon Matta-Clark

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Potential of the City: The Interventions of The Situationist International and Gordon Matta-Clark A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Art History, Theory, and Criticism by Brian James Schumacher Committee in charge: Professor Norman Bryson, Chair Professor Teddy Cruz Professor Grant Kester Professor John Welchman Professor Marcel Henaff 2008 The Thesis of Brian James Schumacher is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii EPIGRAPH The situation is made to be lived by its constructors. Guy Debord Each building generates its own unique situation. Gordon Matta-Clark iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………… iii Epigraph…………………………………………………………………. iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………... v Abstract………………………………………………………………….. vi Chapter 1: Conditions of the City……………………………………….. 1 Chapter 2: Tactics of Resistance………………………………………… 15 Conclusion………………………………………………………………. 31 Notes…………………………………………………………………….. 33 Bibliography…………………………………………………………….. 39 v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Potential of the City: The Interventions of The Situationist International and -

The History of Unitary Urbanism and Psychogeography at the Turn of the Sixties

The History of Unitary Urbanism and Psychogeography at the Turn of the Sixties Ewen Chardronnet 2003 Contents Examples and Comments of Contemporary Psychogeography (lecture notes for a conference in Riga Art + Communication Festival, May 2003) 3 2 Examples and Comments of Contemporary Psychogeography (lecture notes for a conference in Riga Art + Communication Festival, May 2003) The topic of our panel discussion this afternoon is about “local media, maps and psychogeography”. I think it’s necessary to come back first to a brief history of psychogeography, Unitary Urbanism and the Situationnist International at the turn of the sixties. The end of the fifties and the beginning ofthe sixties were a period of acceleration in urbanism of European and world cities. In Paris, this period is the explosion of what politicians and urban planners called “new cities”. Paris was exploding outside its “ring road” and cities such as Sarcelles were created with totally new urban models. There was a strong feeling in that time that the cities were losing their human dimensions. I will first try to show how this acceleration of modernization of urban society had an influence on the tactics of the SI as an avant-garde concerned with the uniformization of society through urbanism, mass media, and the dichotomy of work and leisure. I will especially focus on Unitary Urbanism and 4 years of intense activities (‘58-‘61) that finally culminate by totally abandoning these theories. We will then discuss actual initiatives that use tactical medias in the streets and how this is link to the new rise of psychogeography and the necessity of reclaiming the streets. -

Alternative Spaces in Post-Socialist Prague

Michaela Pixová: Struggle for the Right to the City: Alternative Spaces in Post-Socialist Prague UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE Přírodovědecká fakulta Katedra sociální geografie a regionálního rozvoje Michaela Pixová STRUGGLE FOR THE RIGHT TO THE CITY: ALTERNATIVE SPACES IN POST-SOCIALIST PRAGUE BOJ O PRÁVO NA MĚSTO: ALTERNATIVNÍ PROSTORY V POST-SOCIALISTICKÉ PRAZE Ph.D Thesis The Supervisor: Doc. RNDr. Luděk Sýkora, Ph.D. Prague 2012 Michaela Pixová: Struggle for the Right to the City: Alternative Spaces in Post-Socialist Prague Declaration I declare that this dissertation is my original work conducted under the supervision of Doc. RNDr. Luděk Sýkora, Ph.D. All sources used in the dissertation are indicated by special reference in the text and no part of the dissertation has been submitted for any other degree. Any views expressed in the dissertation are those of the author and in no way represent those of Charles University in Prague. The dissertation has not been presented to any other University for examination either in Czechia or overseas. In Prague, July 30, 2012 ……….…………………… Signature i Michaela Pixová: Struggle for the Right to the City: Alternative Spaces in Post-Socialist Prague Acknowledgement This dissertation could not have been carried out without the help and support of many people. To name all of them would require a long list, and therefore I would like to acknowledge in particular the ones whose help was indispensable to my research and for the production of this thesis. Most of my thanks go obviously to my supervisor, Luděk Sýkora, who not only provided my research with the much needed expertise, but also featured as an invaluable source of inspiration, encouragement and mental support. -

Lynchian Cognitive Mapping and Situationist Psychogeography

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 A critical and historical case study of experience design : Lynchian cognitive mapping and Situationist psychogeography Derek Cori Wallen Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Wallen, Derek Cori, "A critical and historical case study of experience design : Lynchian cognitive mapping and Situationist psychogeography" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 19068. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/19068 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A critical and historical case study of experience design: Lynchian cognitive mapping and Situationist psychogeography by Derek Cori Wallen A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Major: Graphic Design Program of Study Committee: Paula J. Curran, Major Professor Sunghyun Kang Michael J. Golec Carl W. Roberts Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©Derek Cori Wallen, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Derek Cori Wallen has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi ABSTRACT vii CHAPTER 1. -

Libertarian Socialism

Libertarian Socialism PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sun, 12 Aug 2012 19:52:27 UTC Contents Articles Libertarian socialism 1 The Venus Project 37 The Zeitgeist Movement 39 References Article Sources and Contributors 42 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 43 Article Licenses License 44 Libertarian socialism 1 Libertarian socialism Libertarian socialism (sometimes called social anarchism,[1][2] and sometimes left libertarianism)[3][4] is a group of political philosophies that promote a non-hierarchical, non-bureaucratic society without private property in the means of production. Libertarian socialists believe in converting present-day private productive property into the commons or public goods, while retaining respect for personal property[5]. Libertarian socialism is opposed to coercive forms of social organization. It promotes free association in place of government and opposes the social relations of capitalism, such as wage labor.[6] The term libertarian socialism is used by some socialists to differentiate their philosophy from state socialism[7][8] or by some as a synonym for left anarchism.[1][2][9] Adherents of libertarian socialism assert that a society based on freedom and equality can be achieved through abolishing authoritarian institutions that control certain means of production and subordinate the majority to an owning class or political and economic elite.[10] Libertarian socialism also constitutes a tendency of thought that -

Lynch Debord: About Two Psychogeographies1

Lynch Debord: About Two Psychogeographies1 Denis Wood Independent Scholar / Raleigh / NC / USA Abstract Psychogeography emerged entirely independently in Paris in the 1950s and in the Boston area in the 1950s and 1960s, in the wildly disparate practices of the Situationists and of planners and geographers. At the same time that Guy Debord was creating psychogeography in Paris, MIT planning professor Kevin Lynch was laying the groundwork for what at Clark University in the late 1960s became psychogeography for David Stea and his students. Both practices were equally committed to the development of an objective description of the relationship between the urban environment and the psychic life of individuals, both depended heavily on walking as a method, and both produced maps that have become iconic. Keywords: psychogeography, Situationists, Guy Debord, Kevin Lynch, David Stea, Clark University Re´sume´ La psychoge´ographie est ne´e de manie`re comple`tement inde´pendante a` Paris dans les anne´es 1950 ainsi que dans la re´gion de Boston dans les anne´es 1950 et 1960, avec les pratiques tre`s disparates des situationnistes, et de planificateurs et de ge´ographes. En meˆme temps que Guy Debord cre´ait la psychoge´ographie a` Paris, Kevin Lynch, professeur en urbanisation au MIT, e´tablissait les bases de ce qui allait devenir la psychoge´ographie pour David Stea et ses e´tudiants de l’Universite´ Clark, vers la fin des anne´es 1960. Ces me´thodes cherchaient toutes les deux a` de´crire objectivement la relation entre l’environnement urbain et la vie psychique des gens. -

1960 the Path to Unitary Urbanism

The Path to Unitary Urbanism, 1960 This is the only known text by Constant that establishes a link to the Situationist International. Constant was associated with this movement from 1958 to 1960. The texts Constant wrote during the course of the 1950s are an outstanding record of how his conception of space developed into a notion of a complete urban habitat – ‘unitary urbanism’ – and the social space necessary for the development of human creativity. Constant derived the concept of unitary urbanism from Gilles Ivain, the pseudonym of Ivan Chtcheglov, who wrote about it in 1953. When Gil Wolman, a member of the Lettrist International, gave a lecture on this in Alba in 1956, Constant was instantly inspired. Constant elaborated on unitary urbanism with Guy Debord and later used it in his New Babylon project. The Path to Unitary Urbanism This does not involve art. Our life is a game. The world around us is constantly changing. Should we remain on the fringes and leave it to scientists, engineers and politicians to decide the shape of our lives and the world in which we live? There are marvellous inventions with countless opportunities and yet what is lacking is playfulness; we cannot do anything with it. All attempts this century to initiate cultural reforms have failed because they took the individual as their starting point. The collective imagination was not taken into account, was misunderstood or despised. Nevertheless, the face of our world today is largely the result of collective effort. The artist thinks he has to choose between the lack of imagination of industrial functionalism and the impotent scream from the ivory tower. -

Unitary Urbanism: the Internationale Situationniste (1 957-1 972)

1999 ACSA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ROME I49 Unitary Urbanism: the Internationale Situationniste (1957-1 972) LIBERO ANDREOTTI Georgia Institute of Technology 112 Girunz 111zusNocte er Consu~nimurIg~zi: we go round and round in the night and are consumed by fire. The long Latin palindrome used by Guy Debord as the title for oneof his last filmscan also serve to characterize the urban play tactics of the Interrznriorde Sit~mrio~z~~iste.'As Johan Huizinga noted in a book that was a key source for this group- but whose role is all but completely ignored in recent historical writings - the palindrome is in fact an ancient play-form which, like the riddle and the conundrum, "cuts clean across any possible distinction between play and seriousness."* Debord seems aware of this when he notes, somewhat cryptically, that his title is "constructed letter by letter like a labyrinth, in such a way that it conveys perfectly the form and content of perdition" - a remark that can be interpreted in many ways but that recalls the phenomenon of "losing oneself in the game" described so well by Huizinga himself.' Certainly, of all the derounze/ne~ztsfor which Debord is justly farnous, this one seems best suited to convey the iconoclastic spirit of the l~lter~~a~io~zaleSit~rariorzniste (henceforth SI), a movement of great ambition and influence, whose reflections on the city, everyday life, and the spectacle have insured it a vital place in the art and politics of the last forty years. In what follows I would like to explore the play element in the activities -

Contemporary Art, 'Unitary Urbanism'

Resisting Precariousness, Reclaiming Community: Contemporary Art, ‘Unitary Urbanism’ and Urban Futures Amy Melia, Liverpool John Moores University, United Kingdom The European Conference on Arts & Humanities 2019 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract This paper examines instances of contemporary art shaped by the socio-spatial urgencies of capitalist-urbanism, which frequently steer urban communities into precarious conditions such as, exclusionary development, gentrification and housing expropriation. Such works have demonstrated art’s potential to assist communities in acquiring agency over urban futures – even in the context of neo-liberalism’s significant inflammation of said urgencies. This urban-embedded, socially engaged art practice often involves the macro-level discourse of urban regeneration being creatively poached from private, economic interest and handed over to communities. The aim of this paper, however, is not to provide an exhaustive description of this practice, but rather to argue that the Situationist International’s concept of ‘unitary urbanism’ may be repurposed into a critical framework and vocabulary with which it may be examined. The debates of ‘public’ / ‘new genre public art’, ‘street art’ and ‘site-specific art’, for example, have disputably failed to establish a specialised framework for examining contemporary art’s responses to the displacing, expropriating forces of capitalism-urbanism, exacerbated by neo-liberal production. Therefore, this paper proposes that the Situationist’s leftist transmutation of urbanism could function as a potential repository for a qualified theoretical framework and lexicon. The Situationists were a 20th century avant-garde collective who had aimed to critique advanced capitalism and transform the city – two unified objectives, as they had recognised the capitalism-urbanism nexus. -

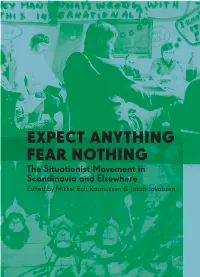

Expect Anything Fear Nothing the Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen 1

ExpEct anything FEar nothing The Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen 1 ExpEcT AnyThing Fear noThing 2 ExpEcT AnyThing Fear noThing The Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere 3 ExpEcT AnyThing Fear noThing ThE SiTuaTionist MovemenT in Scandinavia and Elsewhere ExpEcT AnyThing Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen Fear noThing Published 2011 by nebula in association with autonomedia Nebula Autonomedia ThE SiTuaTionist MovemenT læssøegade 3,4 Po Box 568, williamsburgh Station dK-2200 copenhagen Brooklyn, nY 11211-0568 denmark uSa in Scandinavia www.nebulabooks.dk www.autonomedia.org [email protected] [email protected] and Elsewhere Tel/Fax: 718-963-2603 iSBn 978-87-993651-2-8 ISBn 978-1-57027-232-5 Edited by Editors: Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen | Copyeditor: Marina vishmidt | design: Åse Eg | Inserts: Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen | Proofreading: Mikkel Bolt rasmussen Matt Malooly | Printed by: naryana Press in 2,000 copies | web: destroysi.dk & Jakob Jakobsen Thanks to: The Situationists Fighters (Mie lund hansen, anne Sophie Seiffert, Magnus Fuhr, Robert Kjær clausen, Johannes Balsgaard, Samuel willis nielsen, henrik Busk, david hilmer Rex, Tine Tvergaard, anders hvam waagø, Bue Thastrum, Johannes Busted larsen, Maibritt Pedersen, Kate vinter, odin Rasmussen, Tone andreasen, ask Katzeff and Kirsten Forkert), Peter laugesen, Jacqueline de Jong, Gordon Fazakerley, hardy Strid, Stewart home, Fabian Tompsett, Karen Kurczynski, lars Morell, Tom Mcdonough, Zwi & negator, lis Zwick, ulla Borchenius, henriette heise, Katarina Stenbeck, Stevphen Shukaitis, Jaya Brekke, James Manley, Matt Malooly, Åse Eg and Marina vishmidt. cover images: detourned photo by J.v. Martin of François de Beaulieu, René vienet, J.v. -

Communism 1 Communism

Communism 1 Communism Communism (from Latin communis - common, universal) is a revolutionary socialist movement to create a classless, moneyless, and stateless social order structured upon common ownership of the means of production, as well as a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of this social order.[1] This movement, in its Marxist–Leninist interpretations, significantly influenced the history of the 20th century, which saw intense rivalry between the "socialist world" (socialist states ruled by communist parties) and the "western world" (countries with capitalist economies). Marxist theory holds that pure communism or full communism is a specific stage of historical development that inevitably emerges from the development of the productive forces that leads to a superabundance of material wealth, allowing for distribution based on need and social relations based on freely associated individuals.[2][3] The exact definition of communism varies, and it is often mistakenly, in general political discourse, used interchangeably with socialism; however, Marxist theory contends that socialism is just a transitional stage on the road to communism. Leninism adds to Marxism the notion of a vanguard party to lead the proletarian revolution and to secure all political power after the revolution for the working class, for the development of universal class consciousness and worker participation, in a transitional stage between capitalism and socialism. Council communists and non-Marxist libertarian communists and anarcho-communists oppose the ideas of a vanguard party and a transition stage, and advocate for the construction of full communism to begin immediately upon the abolition of capitalism. There is a very wide range of theories amongst those particular communists in regards to how to build the types of institutions that would replace the various economic engines (such as food distribution, education, and hospitals) as they exist under capitalist systems—or even whether to do so at all.