Wintersloe School

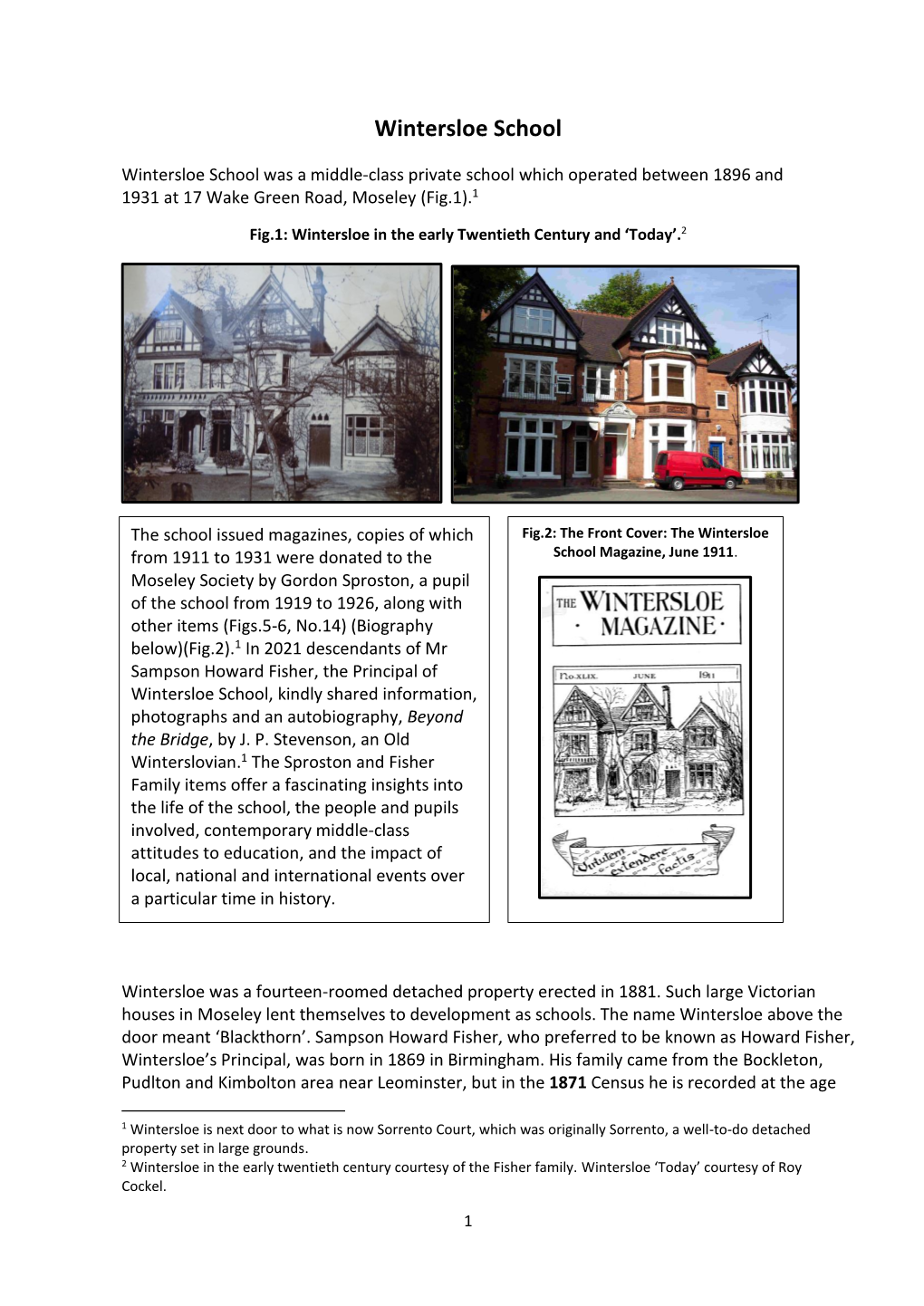

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birmingham City Council Learning, Culture And

BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL LEARNING, CULTURE AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY COMMITTEE WEDNESDAY, 05 DECEMBER 2018 AT 13:30 HOURS IN COMMITTEE ROOMS 3 & 4, COUNCIL HOUSE, VICTORIA SQUARE, BIRMINGHAM, B1 1BB A G E N D A 1 NOTICE OF RECORDING/WEBCAST The Chairman to advise/meeting to note that this meeting will be webcast for live or subsequent broadcast via the Council's Internet site (www.civico.net/birmingham) and that members of the press/public may record and take photographs except where there are confidential or exempt items. 2 APOLOGIES To receive any apologies. 3 DECLARATIONS OF INTERESTS Members are reminded that they must declare all relevant pecuniary and non pecuniary interests arising from any business to be discussed at this meeting. If a disclosable pecuniary interest is declared a Member must not speak or take part in that agenda item. Any declarations will be recorded in the minutes of the meeting. 4 ACTION NOTES 3 - 6 To confirm the action notes of the meeting held on the 14 November 2018. 5 SCHOOL ATTAINMENT AND SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT 7 - 90 Anne Ainsworth, Acting Corporate Director, Children and Young People, Julie Young, Interim AD, Education Safeguarding, Tim Boyes, CEX, Tracy Ruddle, Director of Continuous School Improvement, BEP and Shagufta Anwar, Senior Intelligence Officer in attendance. Page 1 of 106 6 SCHOOL ADMISSIONS AND FAIR ACCESS 91 - 100 Julie Young, Interim AD Education Safeguarding and Alan Michell, Interim Lead for School Admissions and Fair Access in attendance. 7 WORK PROGRAMME 101 - 106 For discussion. 8 DATE OF FUTURE MEETINGS To note the dates of future meetings on the following Wednesdays at 1330 hours in the Council House, Committee Rooms 3 & 4 as follows:- 9 January, 2019 6 February, 2019 6 March, 2019 17 April, 2019 9 REQUEST(S) FOR CALL IN/COUNCILLOR CALL FOR ACTION/PETITIONS RECEIVED (IF ANY) To consider any request for call in/councillor call for action/petitions (if received). -

52 - Sir Frank Benson

52 - SIR FRANK BENSON By Ann Pennington The proudest moment in the life of Frank Benson occurred when he was knighted by King George V during the tercentenary performance of Julius Caesar at Drury Lane in 1916, the first actor to be so honoured within the walls of a theatre. Previously he had been awarded the Freedom of the Borough of Stratford-upon-Avon for his services to Shakespearean theatre. Francis Robert Benson, known by his family as Frank and almost invariably by his fellow Thespians as F.R.B. was the fourth child and third son of William Benson, descended from Quaker stock, and Elizabeth Soulsby Benson (nee Smith), reputed to be one of the most beautiful women of her day. Their grave and memorial is in the New Alresford churchyard. Born in Tunbridge Wells on 4th November 1858, Frank Benson was quite a little boy when the family moved to Langtons, now Langton House, at the corner of East Street and Sun Lane in Alresford. Both house and grounds are much smaller now than when the Bensons, their six children and a battalion of servants lived there. The property included the farm with its paddocks, pastures, stables and grounds with long sloping lawns, flower walks and an enclosed kitchen garden. This was the home Frank Benson remembered in later life with almost passionate affection. Throughout his schooldays his main interests were physical fitness and the love of word and rhythm. In his two final years at Winchester he was Head of House (Wickham's) and had won the straight mile, appropriately on the Alresford road. -

Carers Update from the Carer Support Team

Is the person you care for at risk of pressure ulcers? Birmingham Community Healthcare The following checklists will help you to identify The signs to look for are: NHS Trust their level of risk and the signs that you need to • Not eating as much as usual be looking for, and to know when to ask for help • A problem with a cushion or mattress from your GP who can refer to our Birmingham Community Healthcare District Nursing Team: • Not moving as much as usual Low Risk: Can change position without help or • Sore bottom, heels hips or elbows prompting, have a good appetite and no serious • Chest or urine infection health problems • Incontinence problems Carers Update from the Medium Risk: May have reduced mobility • Sleeping in a chair rather than a bed and require prompting to move regularly, have If the person you care for is already receiving occasional incontinence and a poor appetite services from a district nurse contact the District Carer Support Team High Risk: Cannot change position without help Nurse Message Taking Service, (if services are or prompting, may have persistent incontinence, being received from a district nurse you will have June - August 2012 poor appetite and poor general health. this contact number). Otherwise talk to the GP for a referral. Do you have an email address? If so you could help us to save money and the environment! If you would like to receive your newsletter by email please send your name, postal address Carers Week 2012 18th to 24th June and email address to [email protected] All details will be kept confidentially and not passed to anyone else In Sickness and in Health National Carers Week 2012 is being held on 18-24 For those who wish the MAC is open for We do hope you enjoy the contents of this Newsletter. -

Birmingham Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education

Birmingham Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education Annual Report 2013-2014 www.faithmakesadifference.co.uk S:A:C:R:E 2009-2010 - 1 - Contents 1. SACRE meetings 1 Full Council meetings during 2013/2014 4 The statutory role and responsibilities of SACRE 4 Functions of Officers 2. The Birmingham Agreed Syllabus Developments 2 3. Website and updates 3 4. Collective Worship 4 5. GCSE Results 5 6. DVDs Supporting the Agreed Syllabus 6 7. Determinations for Collective Worship 7 8. SACRE Membership to September 2013-14 9 Committee A Committee B 7 Committee C 8 Committee D 8 Co-option(s) to SACRE 8 Officers in Attendance SACRE Working Groups 9. Appendices 11 9.1: Appendix 1 – Birmingham SACRE Collective Worship 11 Strategy S:A:C:R:E 2013-2014 1. MEETINGS Full SACRE meetings during 2013- The statutory role and 2014 responsibilities of SACRE: 30th September 2013 • To advise the Local Authority (LA) 5th December 2013 upon such matters connected with 10th February 2014 religious worship in community 18th June 2014 schools as the authority may refer to the council or as the council may see fit. For SACRE membership (see appendix) • To advise the LA upon such matters After 8 years of service, Guy Hordern connected with religious education to stepped down as Chair and in May 2012 be given in accordance with the Councillor Dr Barry Henley BSc MSc DBA agreed syllabus in community schools MCIM FCMI took over the role. Dr Henley as the authority may refer to the is a deputy Chair of Governors at council or as the council may see fit. -

Schools and Libraries 2Q2016 Funding Year 2015 Authorizations - 4Q2015 Page 1 of 182

Universal Service Administrative Company Appendix SL27 Schools and Libraries 2Q2016 Funding Year 2015 Authorizations - 4Q2015 Page 1 of 182 Applicant Name City State Primary Authorized 100 ACADEMY OF EXCELLENCE NORTH LAS VEGAS NV 11,790.32 4-J SCHOOL GILLETTE WY 207.11 A + ACADEMY CHARTER SCHOOL DALLAS TX 19,122.48 A + CHILDRENS ACADEMY COMMUNITY SCHOOL COLUMBUS OH 377.16 A B C UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT CERRITOS CA 308,684.37 A SPECIAL PLACE SANTA ROSA CA 8,500.00 A W BEATTIE AVTS DISTRICT ALLISON PARK PA 1,189.32 A+ ARTS ACADEMY COLUMBUS OH 20,277.16 A-C COMM UNIT SCHOOL DIST 262 ASHLAND IL 518.70 A.C.E. CHARTER HIGH SCHOOL TUCSON AZ 1,530.03 A.M. STORY INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL PALESTINE TX 34,799.00 AAA ACADEMY BLUE ISLAND IL 39,446.55 AACL CHARTER SCHOOL COLORADO SPRINGS CO 10,848.59 AAS-ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE SAN DIEGO CA 2,785.82 ABBOTSFORD SCHOOL DISTRICT ABBOTSFORD WI 6,526.23 ABERDEEN PUBLIC LIBRARY ABERDEEN ID 2,291.04 ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 5 ABERDEEN WA 54,176.10 ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 58 ABERDEEN ID 8,059.20 ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 6-1 ABERDEEN SD 13,560.24 ABIDING SAVIOR LUTHERAN SCHOOL SAINT LOUIS MO 320.70 ABINGTON COMMUNITY LIBRARY CLARKS SUMMIT PA 208.81 ABINGTON SCHOOL DISTRICT ABINGTON PA 19,710.58 ABINGTON SCHOOL DISTRICT ABINGTON MA 573.19 ABSAROKEE SCHOOL DIST 52-52 C ABSAROKEE MT 16,093.91 ABSECON PUBLIC LIBRARY ABSECON NJ 372.26 ABUNDANT LIFE CHRISTIAN ACAD MARGATE FL 1,524.99 ACADEMIA ADVENTISTA DEL CENTRO RAMON RIVERA SAN SEBASTIAN PR 1,057.75 PEREZ ACADEMIA ADVENTISTA DEL NORESTE AGUADILLA PR 5,434.40 ACADEMIA ADVENTISTA DEL NORTE ARECIBO PR 7,157.47 ACADEMIA ADVENTISTA DR. -

Name of Group

JOINT SPRINGFIELD WARD & POLICE TASKING MEETING 6 SEPTEMBER 2017 AT MOSELEY SCHOOL, HEALTH & FITNESS CENTRE, SPRINGFIELD ROAD ACTION NOTES In Attendance Councillors Habib Rehman, Shabrana Hussain & Mohammed Fazal Also attending - Kay Thomas, Neighbourhood Development & Support Unit John Mole, Community Development & Support Officer Eddie Fellows, Amey There were 35 residents in attendance. Apologies Sergeant Chughtai Agenda Item Action Cllr Rehman elected as Chair 1. Election of a Chair 2. Notice of Recordings Noted 3. Notes of Last Meeting Noted 4. Police Tasking Issues A police report had been submitted and circulated. The Chair highlighted the spike in burglaries but that the police were following leads to hopefully secure arrests. Two people had been charged with fly tipping at Sarehole Mill & Swanshurst Park Swanshurst Park and a vehicle seized. With regard to the travellers, the Chair injunction - Chair to update at advised that he had a meeting with the Head of Environmental next meeting Health to discuss an injunction for Swanshurst Park, similar to that agreed for parks in Selly Oak. Members of the travelling community referred to comments posted on the B13 News website that were racist and threatening towards travellers. Police had previously stated that hate crime would not be tolerated and therefore action was sought in respect of the comments posted as they lived in constant fear for their safety. The travellers advised that they were working with the Head of Environmental Services to find a site for a transit camp and residents were asked to request that a camp be identified in the City. In response to questions the meeting was advised that the site at Castle Vale was a permanent site and not a transit site. -

Birmingham Museums Birmingham Has One of the Best Civic Museum Collections of Any City in England, All Housed in Nine Wonderful Locations

CONTENTS * 4 - 63 EVERY BIRMINGHAM FESTIVAL in 2020 6 OF THE BEST PLACES YOU MIGHT WANT TO CHECK OUT IN BIRMINGHAM 6 PARKS & WALKS 14 BARS 24 PLACES TO EAT PART ONE 36 MUSIC VENUES 46 MUSEUMS 50 PLACES TO EAT PART TWO 64 INDEX BY CATEGORY 68 CREDITS * IT IS JUST POSSIBLE THAT WE'VE MISSED ONE OR TWO. SEE BIRMINGHAMFESTIVALS.COM FOR UPDATES. II 1 WELCOMEWELCOME “Life is a festival only to the wise” - Ralph Waldo Emerson 2 3 Chinese New Year First Bite & Bite Size JANUARY 18 bit.ly/1stBite2020 MAC Birmingham & Warwick Arts Centre Bite Size and its sister festival First Bite exist to develop and showcase new work from the Midlands. The activity runs across four public events and includes a fully supported commissioning process for three regional theatre makers. Ideas of Noise JANUARY 23 – FEBRUARY 9 bit.ly/IDNoise2020 Birmingham, Stourbridge and Coventry Arts and Science Festival Contemporary classical performance rubs shoulders with electronica, visual art and University of Birmingham Arts & film. This edition of Ideas of Noise spreads Science Festival its programme of cutting edge music, art JAN 2020 - MAY 2020 and interactive events across Birmingham, bit.ly/ArtsnScience2020 Stourbridge and Coventry. JANUARY Various venues across Birmingham Birmingham University’s annual Chinese New Year celebration of research, culture and JANUARY 24–26 collaboration - on and beyond its bit.ly/YearoftheRat2020 Edgbaston campus - is currently Southside, Birmingham showcasing the launch of the University’s Welcome in the Year of the Rat at new Green Heart parkland. Its spring Birmingham’s annual Chinatown gathering, programme sees thinkers, makers and the UK’s largest celebration of the lunar doers engage with the theme ‘Hope’. -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Shylock : a Performance History with Particular Reference to London And

University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. CHAPTER 1 SHYLOCK & PERFORMANCE Such are the controversies which potentially arise from any new production of The Merchant of Venice, that no director or actor can prepare for a fresh interpretation of the character of Shylock without an overshadowing awareness of the implications of getting it wrong. This study is an attempt to describe some of the many and various ways in which productions of The Merchant of Venice have either confronted or side-stepped the daunting theatrical challenge of presenting the most famous Jew in world literature in a play which, most especially in recent times, inescapably lives in the shadow of history. I intend in this performance history to allude to as wide a variety of Shylocks as seems relevant and this will mean paying attention to every production of the play in the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, as well as every major production in London since the time of Irving. For reasons of practicality, I have confined my study to the United Kingdom1 and make few allusions to productions which did not originate in either Stratford or London. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2017, West Midlands

West Midlands Register 2017 HERITAGE AT RISK 2017 / WEST MIDLANDS Contents Heritage at Risk III The Register VII Content and criteria VII Criteria for inclusion on the Register IX Reducing the risks XI Key statistics XIV Publications and guidance XV Key to the entries XVII Entries on the Register by local planning XIX authority Herefordshire, County of (UA) 1 Shropshire (UA) 13 Staffordshire 28 East Staffordshire 28 Lichfield 29 Newcastle-under-Lyme 30 Peak District (NP) 31 South Staffordshire 31 Stafford 32 Staffordshire Moorlands 33 Tamworth 35 Stoke-on-Trent, City of (UA) 35 Telford and Wrekin (UA) 38 Warwickshire 39 North Warwickshire 39 Nuneaton and Bedworth 42 Rugby 42 Stratford-on-Avon 44 Warwick 47 West Midlands 50 Birmingham 50 Coventry 54 Dudley 57 Sandwell 59 Walsall 60 Wolverhampton, City of 61 Worcestershire 63 Bromsgrove 63 Malvern Hills 64 Redditch 67 Worcester 67 Wychavon 68 Wyre Forest 71 II West Midlands Summary 2017 ur West Midlands Heritage at Risk team continues to work hard to reduce the number of heritage assets on the Register. This year the figure has been brought O down to 416, which is 7.8% of the national total of 5,290. While we work to decrease the overall numbers we do, unfortunately, have to add individual sites each year and recognise the challenge posed by a number of long-standing cases. We look to identify opportunities to focus resources on these tough cases. This year we have grant-aided some £1.5m of conservation repairs, Management Agreements and capacity building, covering a wide range of sites. -

An Investigation Into the Claims That Prime Minister James Callaghan's

Dispelling the myths: An investigation into the claims that Prime Minister James Callaghan’s Ruskin College speech was an epoch marking development in secondary education in general and for pre-vocational education in particular. by KEVIN JOHN JERVIS A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Education. The University of Birmingham. Dec 2010. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The origins and developments of pre-vocational education are traditionally traced back to Prime Minister James Callaghan’s speech on 18th October 1976 at Ruskin College, near Oxford. An assertion of this study is that this is a fallacy, with evidence of the existence of pre-vocational education dating back many years before this date. Further it is contended that Callaghan’s speech was not the catalyst for change in aspects of secondary education that many have suggested. The speech was neither a deliberate attempt by Callaghan to challenge the accepted modus operandi of the educational establishment nor an effort to raise standards. On the contrary, this study will argue that Callaghan’s intervention in education was a conscious attempt to distract the attention of commentators away from the worsening social and economic conditions within the U.K, which Callaghan had inherited from Harold Wilson. -

Diving In: a Future for Moseley Road Baths

Diving in: a future for Moseley Road Baths The expert view ‘Nowadays most of us take for granted the facility to wash daily in hot water, to dress in clean laundered clothes, and when we choose to swim, to do so in a hygienic, safe environment (one reason why swimming is now the nation's second most popular form of recreation, after walking). Opened in 1907, Moseley Road Baths is a glowing reminder of how we attained these basic privileges. Courtesy of progressive civic leaders and innovative engineers and architects – not for nothing did the Victorians regard themselves as the new Romans – Britain led the newly industrialised world in terms of public baths provision. In today’s England only around 40 such examples from that era survive, and the number diminishes every year. Of those that do still operate, most have lost many of their original features. Moseley Road Baths, by contrast – the only pre-war public baths that is listed Grade II* and remains in use for swimming – is an extraordinary survivor. Both its opulent exterior and interior are almost completely intact. Its Gala Pool, although closed since 2003, remains one the grandest of its kind ever seen. Also, its slipper baths sections for men and women are by far the largest and best preserved in Britain. Until the 1960s the majority of households didn't have their own baths, so facilities such as these played a key role in people’s weekly routines (my mother’s included). In 1907 it was Birmingham rate payers who footed the bill for this municipal masterpiece.