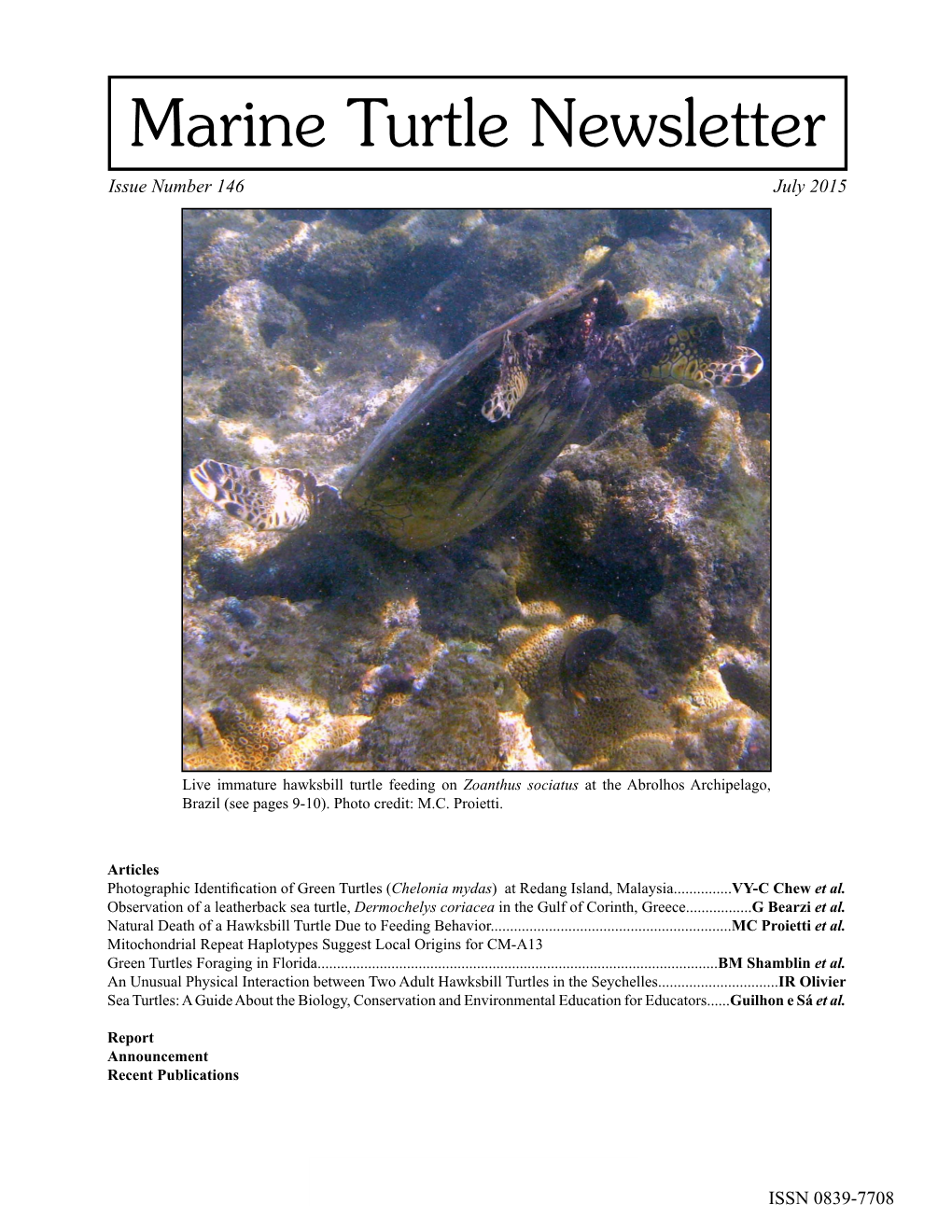

Marine Turtle Newsletter Issue Number 146 July 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Osseous Growth and Skeletochronology

Comparative Ontogenetic 2 and Phylogenetic Aspects of Chelonian Chondro- Osseous Growth and Skeletochronology Melissa L. Snover and Anders G.J. Rhodin CONTENTS 2.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 17 2.2 Skeletochronology in Turtles ................................................................................................ 18 2.2.1 Background ................................................................................................................ 18 2.2.1.1 Validating Annual Deposition of LAGs .......................................................20 2.2.1.2 Resorption of LAGs .....................................................................................20 2.2.1.3 Skeletochronology and Growth Lines on Scutes ......................................... 21 2.2.2 Application of Skeletochronology to Turtles ............................................................. 21 2.2.2.1 Freshwater Turtles ........................................................................................ 21 2.2.2.2 Terrestrial Turtles ......................................................................................... 21 2.2.2.3 Marine Turtles .............................................................................................. 21 2.3 Comparative Chondro-Osseous Development in Turtles......................................................22 2.3.1 Implications for Phylogeny ........................................................................................32 -

Mesozoic Marine Reptile Palaeobiogeography in Response to Drifting Plates

ÔØ ÅÒÙ×Ö ÔØ Mesozoic marine reptile palaeobiogeography in response to drifting plates N. Bardet, J. Falconnet, V. Fischer, A. Houssaye, S. Jouve, X. Pereda Suberbiola, A. P´erez-Garc´ıa, J.-C. Rage, P. Vincent PII: S1342-937X(14)00183-X DOI: doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2014.05.005 Reference: GR 1267 To appear in: Gondwana Research Received date: 19 November 2013 Revised date: 6 May 2014 Accepted date: 14 May 2014 Please cite this article as: Bardet, N., Falconnet, J., Fischer, V., Houssaye, A., Jouve, S., Pereda Suberbiola, X., P´erez-Garc´ıa, A., Rage, J.-C., Vincent, P., Mesozoic marine reptile palaeobiogeography in response to drifting plates, Gondwana Research (2014), doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2014.05.005 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Mesozoic marine reptile palaeobiogeography in response to drifting plates To Alfred Wegener (1880-1930) Bardet N.a*, Falconnet J. a, Fischer V.b, Houssaye A.c, Jouve S.d, Pereda Suberbiola X.e, Pérez-García A.f, Rage J.-C.a and Vincent P.a,g a Sorbonne Universités CR2P, CNRS-MNHN-UPMC, Département Histoire de la Terre, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 38, 57 rue Cuvier, -

Comparative Bone Histology of the Turtle Shell (Carapace and Plastron)

Comparative bone histology of the turtle shell (carapace and plastron): implications for turtle systematics, functional morphology and turtle origins Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn Vorgelegt von Dipl. Geol. Torsten Michael Scheyer aus Mannheim-Neckarau Bonn, 2007 Angefertigt mit Genehmigung der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn 1 Referent: PD Dr. P. Martin Sander 2 Referent: Prof. Dr. Thomas Martin Tag der Promotion: 14. August 2007 Diese Dissertation ist 2007 auf dem Hochschulschriftenserver der ULB Bonn http://hss.ulb.uni-bonn.de/diss_online elektronisch publiziert. Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Januar 2007 Institut für Paläontologie Nussallee 8 53115 Bonn Dipl.-Geol. Torsten M. Scheyer Erklärung Hiermit erkläre ich an Eides statt, dass ich für meine Promotion keine anderen als die angegebenen Hilfsmittel benutzt habe, und dass die inhaltlich und wörtlich aus anderen Werken entnommenen Stellen und Zitate als solche gekennzeichnet sind. Torsten Scheyer Zusammenfassung—Die Knochenhistologie von Schildkrötenpanzern liefert wertvolle Ergebnisse zur Osteoderm- und Panzergenese, zur Rekonstruktion von fossilen Weichgeweben, zu phylogenetischen Hypothesen und zu funktionellen Aspekten des Schildkrötenpanzers, wobei Carapax und das Plastron generell ähnliche Ergebnisse zeigen. Neben intrinsischen, physiologischen Faktoren wird die -

(Chelonioidea: Cheloniidae) from the Maastrichtian of the Harrana Fauna–Jordan

Kaddumi, Gigantatypus salahi n.gen., n.sp., from Harrana www.PalArch.nl, vertebrate palaeontology, 3, 1, (2006) A new genus and species of gigantic marine turtles (Chelonioidea: Cheloniidae) from the Maastrichtian of the Harrana Fauna–Jordan H.F. Kaddumi Eternal River Museum of Natural History Amman–Jordan, P.O. Box 11395 [email protected] ISSN 1567–2158 7 figures Abstract Marine turtle fossils are extremely rare in the Muwaqqar Chalk Marl Formation of the Harrana Fauna in comparison to the relatively rich variety of other vertebrate fossils collected from this locality. This paper reports and describes the remains of an extinct marine turtle (Chelonioidea) which will be tentatively assigned to a new genus and species of marine turtles (Cheloniidae Bonaparte, 1835) Gigantatypus salahi n.gen., n.sp.. The new genus represented by a single well–preserved right humerus, reached remarkably large proportions equivalent to that of Archelon Wieland, 1896 and represents the first to be found from this deposit and from the Middle East. The specimen, which exhibits unique combinations of features is characterized by the following morphological features not found in other members of the Cheloniidae: massive species reaching over 12 feet in length; a more prominently enlarged lateral process that is situated more closely to the head; a ventrally situated capitellum; a highly laterally expanded distal margin. The presence of these features may warrant the placement of this new species in a new genus. The specimen also retains some morphological features found in members of advanced protostegids indicating close affinities with the family. Several bite marks on the ventral surface of the fossilized humerus indicate shark–scavenging activities of possibly Squalicorax spp. -

Bone Damage in Allopleuron Hofmanni (Cheloniidae, Late Cretaceous)•

Netherlands Journal of Geosciences — Geologie en Mijnbouw | 92 – 2/3 | 153-157 | 2013 Bone damage in Allopleuron hofmanni (Cheloniidae, Late Cretaceous)• R. Janssen1,*, R.R. van Baal1 & A.S. Schulp1,2,3 1 Faculty of Earth and Life Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1085, 1081 HV Amsterdam, the Netherlands 2 Natuurhistorisch Museum Maastricht, De Bosquetplein 6-7, 6211 KJ Maastricht, the Netherlands 3 Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, the Netherlands * Corresponding author. Email address: [email protected] Manuscript received: January 2013; accepted: May 2013 Abstract We describe pathologies and post-mortem damage observed in specimens of the late Maastrichtian marine cheloniid turtle Allopleuron hofmanni. Shallow circular lesions on carapace bones are common and possibly illustrate barnacle attachment/embedment. Deep, pit-like marks are confined to the neural rim and the inner surface of peripheral elements; these may have been caused either by barnacle attachment or disease. A number of linear marks found on outer carapace surfaces are identified as tooth marks of scavengers, others as possible domichnia of boring bivalves. A fragmentary scapula and prescapular process displays radular traces of molluscs (gastropods and/or polyplacophorans; ichnogenus Radulichnus). These diverse types of bone damage suggest both live and dead marine turtles to have been commonly utilised by predators, scavengers and encrusters in the type Maastrichtian marine ecosystem. Keywords: Testudines, Maastrichtian, pathology, scavenging, molluscs, barnacles Introduction Whereas several palaeopathological studies on Maastrichtian type area mosasaurs have been conducted (Dortangs et al., 2002; To date, the latest Cretaceous (late Maastrichtian) marine turtle Schulp et al., 2004; Rothschild & Martin, 2005; Rothschild et Allopleuron hofmanni (Gray, 1831) is known exclusively from al., 2005), less is known about the pathologies of other type the Maastrichtian type area in the southeast Netherlands and Maastrichtian reptiles such as A. -

New Sea Turtle from the Miocene of Peru and the Iterative Evolution of Feeding Ecomorphologies Since the Cretaceous

J. Paleont., 84(2), 2010, pp. 231–247 Copyright ’ 2010, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/10/0084-0231$03.00 NEW SEA TURTLE FROM THE MIOCENE OF PERU AND THE ITERATIVE EVOLUTION OF FEEDING ECOMORPHOLOGIES SINCE THE CRETACEOUS JAMES F. PARHAM1,2 AND NICHOLAS D. PYENSON3–5 1Biodiversity Synthesis Center, Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605, USA, ,[email protected].; 2Department of Herpetology, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Concourse Drive, San Francisco 94118, USA, ,[email protected].; 3Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, #2370-6270 University Boulevard, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada; 4Departments of Mammalogy and Paleontology, Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, Seattle, WA 98195, USA; and 5Current address: Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, MRC 121, P.O. Box 37012, Washington DC 20013-7012, USA ABSTRACT—The seven species of extant sea turtles show a diversity of diets and feeding specializations. Some of these species represent distinctive ecomorphs that can be recognized by osteological characters and therefore can be identified in fossil taxa. Specifically, modifications to the feeding apparatus for shearing or crushing (durophagy) are easily recognizable in the cranium and jaw. New sea turtle fossils from the Miocene of Peru, described as a new genus and species (Pacifichelys urbinai n. gen. and n. sp.), correspond to the durophagous ecomorph. This new taxon is closely related to a recently described sea turtle from the middle Miocene of California, USA (Pacifichelys hutchisoni n. comb.), providing additional information on the osteological characters of this lineage. -

1 APPENDIX S1 to Evers, Barrett & Benson 2018

APPENDIX S1 to Evers, Barrett & Benson 2018: Anatomy of Rhinochelys pulchriceps (Protostegidae) and marine adaptation during the early evolution of chelonioids Table of Contents ADDITIONAL CT DATA INFORMATION p. 2 ADDITIONAL ANATOMICAL ILLUSTRATIONS p. 3 CHARACTER MODIFICATIONS p. 24 SCORING SOURCES p. 46 CHARACTER OPTIMIZATION p. 51 Methods p. 51 Results p. 52 PCA DATA p. 80 PCA USING MEASUREMENTS OF COLLINS (1970) p. 83 Methods p. 83 Results p. 83 INSTITUTIONAL ABBREVIATIONS p. 85 REFERENCES p. 86 1 ADDITIONAL CT DATA INFORMATION TABLE S1.1. Information about Rhinochelys specimens that were CT scanned for this study. Taxonomy (sensu Voxel size Specimen number Holotype Scanning facility CT Scanner Data availability Reference Collins [1970]) (mm) NHMUK Imaging and Nikon XT H MorphoSource Media CAMSM B55775 R. pulchriceps R. pulchriceps 0.0355 This study Analysis Center 225 ST Group M29973 NHMUK Imaging and Nikon XT H MorphoSource Media NHMUK PV R2226 R. elegans R. elegans 0.0351 This study Analysis Center 225 ST Group M29987 NHMUK Imaging and Nikon XT H MorphoSource Media NHMUK PV OR43980 R. cantabrigiensis R. cantabrigiensis 0.025 This study Analysis Center 225 ST Group M29986 NHMUK Imaging and Nikon XT H MorphoSource Media Evers & Benson CAMSM B55783 - R. cantabrigiensis 0.0204 Analysis Center 225 ST Group M22140 (2018) NHMUK Imaging and Nikon XT H MorphoSource Media CAMSM B55776 - R. elegans 0.0282 This study Analysis Center 225 ST Group M29983 NHMUK Imaging and Nikon XT H MorphoSource Media NHMUK PV OR35197 - R. elegans 0.0171 This study Analysis Center 225 ST Group M29984 2 ADDITIONAL ANATOMICAL ILLUSTRATIONS The following illustrations are provided as additional guides for the description provided in the main text of this paper. -

Dutch Pioneers of the Earth Sciences

Dutch pioneers of the earth sciences History of Science and Scholarship in the Netherlands, volume The series History of Science and Scholarship in the Netherlands presents studies on a variety of subjects in the history of science, scholarship and academic insti- tutions in the Netherlands. Titles in this series . Rienk Vermij, The Calvinist Copernicans. The reception of the new astronomy in the Dutch Republic, -. , --- . Gerhard Wiesenfeldt, Leerer Raum in Minervas Haus. Experimentelle Natur- lehre an der Universität Leiden, -. , --- . Rina Knoeff, Herman Boerhaave (-). Calvinist chemist and physician. , --- . Johanna Levelt Sengers, How fluids unmix. Discoveries by the School of Van der Waals and Kamerlingh Onnes, , --- . Jacques L.R. Touret and Robert P.W. Visser, editors, Dutch pioneers of the earth sciences, , --- Editorial Board K. van Berkel, University of Groningen W.Th.M. Frijhoff, Free University of Amsterdam A. van Helden, Utrecht University W.E. Krul, University of Groningen A. de Swaan, Amsterdam School of Sociological Research R.P.W. Visser, Utrecht University Dutch pioneers of the earth sciences Edited by Jacques L.R. Touret and Robert P.W. Visser Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Amsterdam Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences P.O. Box , GC Amsterdam, the Netherlands T + - F+ - E [email protected] www.knaw.nl --- The paper in this publication meets the requirements of « iso-norm () for permanence © Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

The Head and Neck Anatomy of Sea Turtles (Cryptodira: Chelonioidea) and Skull Shape in Testudines

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2012 The Head and Neck Anatomy of Sea Turtles (Cryptodira: Chelonioidea) and Skull Shape in Testudines Jones, Marc E H ; Werneburg, Ingmar ; Curtis, Neil ; Penrose, Rod ; O’Higgins, Paul ; Fagan, Michael J ; Evans, Susan E DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047852 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-94813 Journal Article Published Version The following work is licensed under a Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License. Originally published at: Jones, Marc E H; Werneburg, Ingmar; Curtis, Neil; Penrose, Rod; O’Higgins, Paul; Fagan, Michael J; Evans, Susan E (2012). The Head and Neck Anatomy of Sea Turtles (Cryptodira: Chelonioidea) and Skull Shape in Testudines. PLoS ONE, 7(11):e47852. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047852 The Head and Neck Anatomy of Sea Turtles (Cryptodira: Chelonioidea) and Skull Shape in Testudines Marc E. H. Jones1*, Ingmar Werneburg2,3,4, Neil Curtis5, Rod Penrose6, Paul O’Higgins7, Michael J. Fagan5, Susan E. Evans1 1 Research Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, UCL, University College London, London, England, United Kingdom, 2 Eberhard Karls Universita¨t, Fachbereich Geowissenschaften, Tu¨bingen, Germany, 3 RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, Chuo-ku, Kobe, Japan, 4 Pala¨ontologisches Institut und Museum der Universita¨t Zu¨rich, Zu¨rich, Switzerland, 5 Department of Engineering, University of Hull, Hull, England, United Kingdom, 6 United Kingdom Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme, Marine Environmental Monitoring, Penwalk, Llechryd, Caredigion, Cymru, United Kingdom, 7 Centre for Anatomical and Human Sciences, The Hull York Medical School, University of York, York, England, United Kingdom Abstract Background: Sea turtles (Chelonoidea) are a charismatic group of marine reptiles that occupy a range of important ecological roles. -

Qt147611bv.Pdf

UC Berkeley PaleoBios Title Oldest known marine turtle? A new protostegid from the Lower Cretaceous of Colombia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/147611bv Journal PaleoBios, 32(1) ISSN 0031-0298 Authors Cadena, Edwin A Parham, James F Publication Date 2015-09-07 DOI 10.5070/P9321028615 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/147611bv#supplemental Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California PaleoBios 32:1–42, September 7, 2015 PaleoBios OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY Edwin A. Cadena and James F. Parham (2015). Oldest known marine turtle? A new protostegid from the Lower Cretaceous of Colombia. Cover illustration: Desmatochelys padillai on an early Cretaceous beach. Reconstruction by artist Jorge Blanco, Argentina. Citation: Cadena, E.A. and J.F. Parham. 2015. Oldest known marine turtle? A new protostegid from the Lower Cretaceous of Colombia. PaleoBios 32. ucmp_paleobios_28615. PaleoBios 32:1–42, September 7, 2015 Oldest known marine turtle? A new protostegid from the Lower Cretaceous of Colombia EDWIN A. CADENA1, 2*AND JAMES F. PARHAM3 1 Centro de Investigaciones Paleontológicas, Villa de Leyva, Colombia; [email protected]. 2 Department of Paleoherpetology, Senckenberg Naturmuseum, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany. 3John D. Cooper Archaeological and Paleontological Center, Department of Geological Sciences, California State University, Fullerton, CA 92834, USA; [email protected]. Recent studies suggested that many fossil marine turtles might not be closely related to extant marine turtles (Che- lonioidea). The uncertainty surrounding the origin and phylogenetic position of fossil marine turtles impacts our understanding of turtle evolution and complicates our attempts to develop and justify fossil calibrations for molecular divergence dating. -

The Head and Neck Anatomy of Sea Turtles (Cryptodira: Chelonioidea) and Skull Shape in Testudines

The Head and Neck Anatomy of Sea Turtles (Cryptodira: Chelonioidea) and Skull Shape in Testudines Marc E. H. Jones1*, Ingmar Werneburg2,3,4, Neil Curtis5, Rod Penrose6, Paul O’Higgins7, Michael J. Fagan5, Susan E. Evans1 1 Research Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, UCL, University College London, London, England, United Kingdom, 2 Eberhard Karls Universita¨t, Fachbereich Geowissenschaften, Tu¨bingen, Germany, 3 RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, Chuo-ku, Kobe, Japan, 4 Pala¨ontologisches Institut und Museum der Universita¨t Zu¨rich, Zu¨rich, Switzerland, 5 Department of Engineering, University of Hull, Hull, England, United Kingdom, 6 United Kingdom Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme, Marine Environmental Monitoring, Penwalk, Llechryd, Caredigion, Cymru, United Kingdom, 7 Centre for Anatomical and Human Sciences, The Hull York Medical School, University of York, York, England, United Kingdom Abstract Background: Sea turtles (Chelonoidea) are a charismatic group of marine reptiles that occupy a range of important ecological roles. However, the diversity and evolution of their feeding anatomy remain incompletely known. Methodology/Principal Findings: Using computed tomography and classical comparative anatomy we describe the cranial anatomy in two sea turtles, the loggerhead (Caretta caretta) and Kemp’s ridley (Lepidochelys kempii), for a better understanding of sea turtle functional anatomy and morphological variation. In both taxa the temporal region of the skull is enclosed by bone and the jaw joint structure and muscle arrangement indicate that palinal jaw movement is possible. The tongue is relatively small, and the hyoid apparatus is not as conspicuous as in some freshwater aquatic turtles. We find several similarities between the muscles of C. -

UC Berkeley Paleobios

UC Berkeley PaleoBios Title Paleogene chelonians from Maryland and Virginia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7253p3tf Journal PaleoBios, 31(1) ISSN 0031-0298 Author Weems, Robert E. Publication Date 2014-05-27 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California PaleoBios 31(1):1–32, May 27, 2014 Paleogene chelonians from Maryland and Virginia ROBERT E. WEEMS Paleo Quest, 14243 Murphy Terrace, Gainesville, Virginia, 20155, USA; [email protected] Fossil remains of 22 kinds of Paleogene turtles have been recovered in Maryland and Virginia from the early Paleocene Brightseat Formation (four taxa), late Paleocene Aquia Formation (nine taxa), early Eocene Nanje- moy Formation (five taxa), middle Eocene Piney Point Formation (one taxon), and mid-Oligocene Old Church Formation (three taxa). Twelve taxa are clearly marine forms, of which ten are pancheloniids (Ashleychelys palmeri, Carolinochelys wilsoni, Catapleura coatesi, Catapleura sp., Euclastes roundsi, E. wielandi, ?Lophochelys sp., Procolpochelys charlestonensis, Puppigerus camperi, and Tasbacka ruhoffi), and two are dermochelyids (Eosphargis insularis and cf. Eosphargis gigas). Eight taxa represent fluvial or terrestrial forms (Adocus sp., Judithemys kranzi n. sp., Planetochelys savoiei, cf. “Trionyx” halophilus, “Trionyx” pennatus, “Kinosternoid B,” Bothremydinae gen. et sp. indet., and Bothremydidae gen. et sp. indet.), and two taxa (Aspideretoides virgin- ianus and Allaeochelys sp.) are trionychian turtles that probably frequented estuarine and nearshore marine environments. In Maryland and Virginia, turtle diversity superficially appears to decline throughout the Pa- leogene, but this probably is due to an upward bias in the local stratigraphic column toward more open marine environments that have preserved very few remains of riverine or terrestrial turtles.