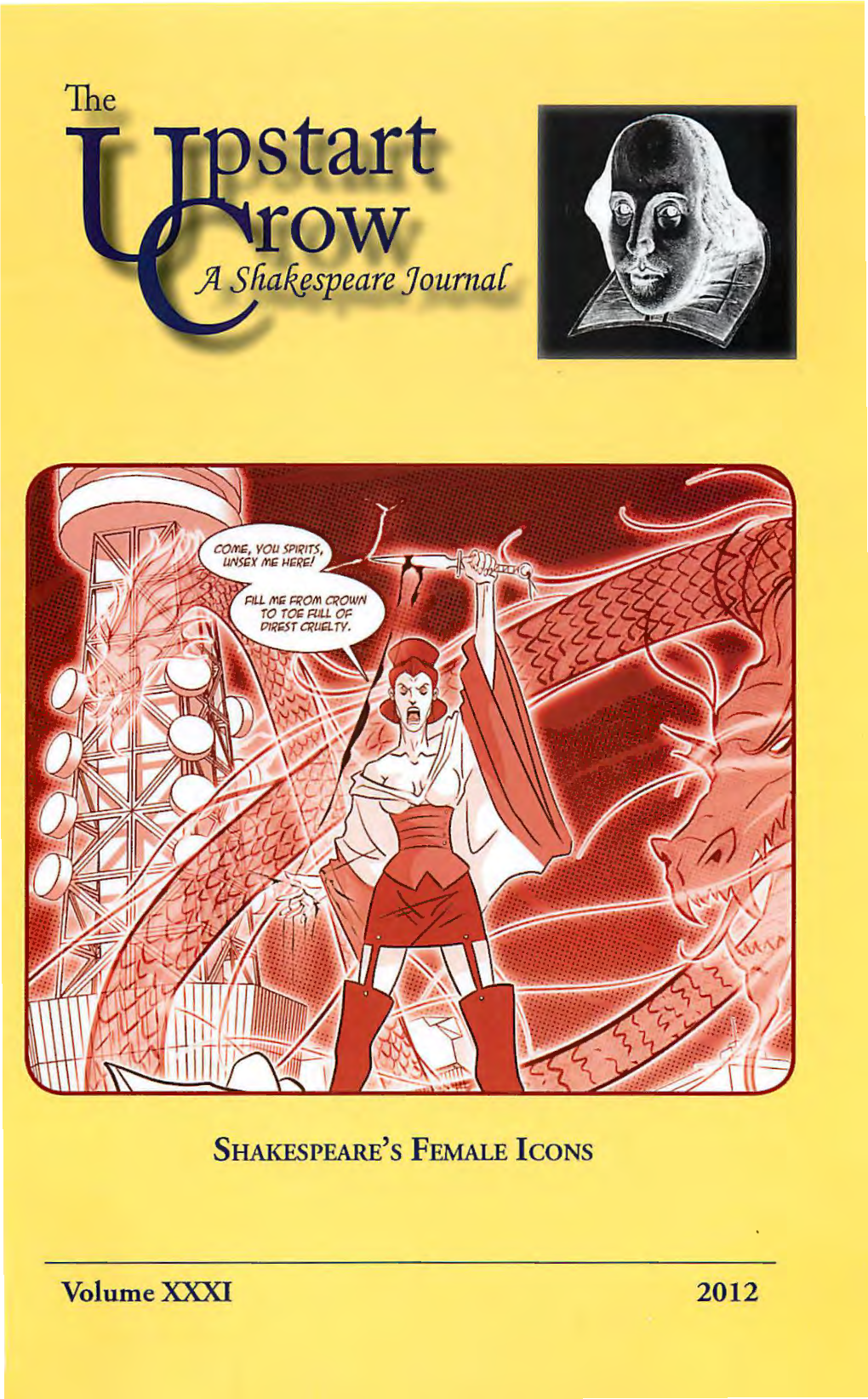

SHAKESPEARE's FEMALE Icons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Death of Captain Cook in Theatre 224

The Many Deaths of Captain Cook A Study in Metropolitan Mass Culture, 1780-1810 Ruth Scobie PhD University of York Department of English April 2013 i Ruth Scobie The Many Deaths of Captain Cook Abstract This thesis traces metropolitan representations, between 1780 and 1810, of the violent death of Captain James Cook at Kealakekua Bay in Hawaii. It takes an interdisciplinary approach to these representations, in order to show how the interlinked texts of a nascent commercial culture initiated the creation of a colonial character, identified by Epeli Hau’ofa as the looming “ghost of Captain Cook.” The introduction sets out the circumstances of Cook’s death and existing metropolitan reputation in 1779. It situates the figure of Cook within contemporary mechanisms of ‘celebrity,’ related to notions of mass metropolitan culture. It argues that previous accounts of Cook’s fame have tended to overemphasise the immediacy and unanimity with which the dead Cook was adopted as an imperialist hero; with the result that the role of the scene within colonialist histories can appear inevitable, even natural. In response, I show that a contested mythology around Cook’s death was gradually constructed over the three decades after the incident took place, and was the contingent product of a range of texts, places, events, and individuals. The first section examines responses to the news of Cook’s death in January 1780, focusing on the way that the story was mediated by, first, its status as ‘news,’ created by newspapers; and second, the effects on Londoners of the Gordon riots in June of the same year. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

DOC-WEB-1.6.18.Pdf

King William IV, monarch of England, reigned from 1830 until his death in 1837. William served in the Royal Navy in his youth and was, both during his reign and afterwards, nicknamed the "Sailor King". He served in North America and the Carribean. In 1789, he was crowned The Duke of Clarence and St Andrew's. Since his two older brothers died without leaving legitimate issue, he unexpectedly inherited the throne when he was 64 years old. His reign saw several reforms: the poor law was updated, child labour restricted, slavery abolished in nearly all the British Empire, and the British electoral system refashioned by the Reform Act 1832. At the time of his death William had no surviving legitimate children, but he was survived by eight of the ten illegitimate children he had by the actress Dorothea Jordan, with whom he cohabited for 20 years. William was succeeded in the United Kingdom by his niece, Victoria, and in Hanover by his brother, Ernest Augustus. Clarence Street was named in honour of "The Duke Of Clarence". I N D E X Food 1 Clarence Cocktails 2 Old & Forgotten 3 Cups & Punches 4 Vintage Pimm's 4 Beer Selection 5 Sparkling & Champagne 6 White Wine 7 Red Wine 8 Rosé & Fortified Wine 9 Gin Selection 10 Irish Whiskey 13 English Whisky 14 Welsh Whisky 14 Australian Whisky 14 North American Whiskey 14 Japanese Whisky 14 Scotch Whisky 15 Rum / Rhum 18 Tequila / Mezcal 18 Cognac 19 Armagnac 19 Calvados 19 Vodka 19 Pastis / Absinthe 19 Credit Card Fees 1.5% Visa / Mastercard / EFTPOS 3% American Express L U N C H D I S H E S Fish and -

TREFOR PROUD Make-Up Artist IATSE 706 Journeyman Member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

TREFOR PROUD Make-Up Artist IATSE 706 Journeyman Member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences FILM MR. CHURCH Make-Up Department Head Director: Bruce Beresford Cast: Britt Robertson, Xavier Samuel, Christian Madsen SPY Make-Up Department Head Director: Paul Feig Cast: Jason Statham, Rose Byrme, Peter Serafinowicz, Julian Miller THE PURGE 2 - ANARCHY Make-Up Department Head and Mask Design Director: James DeMonaco Cast: Michael K. Williams, Frank Grillo, Carmen Ejogo BONNIE AND CLYDE Make-Up Department Head Director: Bruce Beresford Cast: Emile Hirsch, Holly Hunter, William Hurt, Sarah Hyland Nominee: Emmy – Outstanding Make-Up for a Miniseries or a Movie (Non-Prosthetic) ENDER’S GAME Make-Up Department Head Director: Gavin Hood Cast: Harrison Ford, Asa Butterfield, Sir Ben Kingsley JACK REACHER Make-Up Department Head Director: Christopher McQuarrie Cast: Rosamund Pike, Robert Duvall THE RITE Make-Up and Hair Designer Director: Mikael Håfström Cast: Alice Braga, Anthony Hopkins, Ciarán Hinds A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET Department Head Make-Up, Los Angeles Director: Samuel Bayer Cast: Jackie Earle Hayley, Kyle Gallner, Rooney Mara, Katie Cassidy, Thomas Dekker, Kellan Lutz, Clancy Brown LONDON DREAMS Make-Up and Hair Designer Director: Vipul Amrutlal Shah Cast: Salman Khan, Ajay Devgan, Asin, THE COURAGEOUS HEART Make-Up and Hair Department Head OF IRENA SENDLER Director: John Kent Harrison Hallmark Hall of Fame Cast: Anna Paquin, Goran Visnjic, Marcia Gay Harden Winner: Emmy for Outstanding Make-Up for a Miniseries or Movie -

Religious Studies 181B Political Islam and the Response of Iranian

Religious Studies 181B Political Islam and the Response of Iranian Cinema Fall 2012 Wednesdays 5‐7:50 PM HSSB 3001E PROFESSOR JANET AFARY Office: HSSB 3047 Office Hours; Wednesday 2:00‐3:00 PM E‐Mail: [email protected] Assistant: Shayan Samsami E‐Mail: [email protected] Course Description Artistic Iranian Cinema has been influenced by the French New Wave and Italian neorealist styles but has its own distinctly Iranian style of visual poetry and symbolic lanGuaGe, brinGinG to mind the delicate patterns and intricacies of much older Iranian art forms, the Persian carpet and Sufi mystical poems. The many subtleties of Iranian Cinema has also stemmed from the filmmakers’ need to circumvent the harsh censorship rules of the state and the financial limitations imposed on independent filmmakers. Despite these limitations, post‐revolutionary Iranian Cinema has been a reGular feature at major film festivals around the Globe. The minimalist Art Cinema of Iran often blurs the borders between documentary and fiction films. Directors employ non‐professional actors. Male and female directors and actors darinGly explore the themes of Gender inequality and sexual exploitation of women in their work, even thouGh censorship laws forbid female and male actors from touchinG one another. In the process, filmmakers have created aesthetically sublime metaphors that bypass the censors and directly communicate with a universal audience. This course is an introduction to contemporary Iranian cinema and its interaction with Political Islam. Special attention will be paid to how Iranian Realism has 1 developed a more tolerant discourse on Islam, culture, Gender, and ethnicity for Iran and the Iranian plateau, with films about Iran, AfGhanistan, and Central Asia. -

Actors' Stories Are a SAG Awards® Tradition

Actors' Stories are a SAG Awards® Tradition When the first Screen Actors Guild Awards® were presented on March 8, 1995, the ceremony opened with a speech by Angela Lansbury introducing the concept behind the SAG Awards and the Actor® statuette. During her remarks she shared a little of her own history as a performer: "I've been Elizabeth Taylor's sister, Spencer Tracy's mistress, Elvis' mother and a singing teapot." She ended by telling the audience of SAG Awards nominees and presenters, "Tonight is dedicated to the art and craft of acting by the people who should know about it: actors. And remember, you're one too!" Over the Years This glimpse into an actor’s life was so well received that it began a tradition of introducing each Screen Actors Guild Awards telecast with a distinguished actor relating a brief anecdote and sharing thoughts about what the art and craft mean on a personal level. For the first eight years of the SAG Awards, just one actor performed that customary opening. For the 9th Annual SAG Awards, however, producer Gloria Fujita O'Brien suggested a twist. She observed it would be more representative of the acting profession as a whole if several actors, drawn from all ages and backgrounds, told shorter versions of their individual journeys. To add more fun and to emphasize the universal truths of being an actor, the producers decided to keep the identities of those storytellers secret until they popped up on camera. An August Lineage Ever since then, the SAG Awards have begun with several of these short tales, typically signing off with his or her name and the evocative line, "I Am an Actor™." So far, audiences have been delighted by 107 of these unique yet quintessential Actors' Stories. -

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Thursday, 05/20/10, 09:41 AM

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Thursday, 05/20/10, 09:41 AM Holden Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.1 3.0 English Fiction 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea Jon Buller LG 2.6 0.5 English Fiction 11592 2095 Jon Scieszka MG 4.8 2.0 English Fiction 6201 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen LG 3.1 2.0 English Fiction 30629 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola LG 4.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 166 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson MG 5.2 5.0 English Fiction 9001 The 500 Hats of Bartholomew CubbinsDr. Seuss LG 3.9 1.0 English Fiction 413 The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson MG 4.3 2.0 English Fiction 11151 Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner LG 2.6 0.5 English Nonfiction 61248 Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved BooksKay Winters LG 3.6 0.5 English Nonfiction 101 Abel's Island William Steig MG 6.2 3.0 English Fiction 13701 Abigail Adams: Girl of Colonial Days Jean Brown Wagoner MG 4.2 3.0 English Nonfiction 9751 Abiyoyo Pete Seeger LG 2.8 0.5 English Fiction 907 Abraham Lincoln Ingri & Edgar d'Aulaire 4.0 1.0 English 31812 Abraham Lincoln (Pebble Books) Lola M. Schaefer LG 1.5 0.5 English Nonfiction 102785 Abraham Lincoln: Sixteenth President Mike Venezia LG 5.9 0.5 English Nonfiction 6001 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith LG 5.0 3.0 English Fiction 102 Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt MG 8.9 11.0 English Fiction 7201 Across the Stream Mirra Ginsburg LG 1.2 0.5 English Fiction 17602 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie:Kristiana The Oregon Gregory Trail Diary.. -

The Importance of the Weimar Film Industry Redacted for Privacy Abstract Approved: Christian P

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Tamara Dawn Goesch for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies in Foreign Languages and Litera- tures (German), Business, and History presented on August 12, 1981 Title: A Critique of the Secondary Literature on Weimar Film; The Importance of the Weimar Film Industry Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: Christian P. Stehr Only when all aspects of the German film industry of the 1920's have been fully analyzed and understood will "Weimar film" be truly comprehensible. Once this has been achieved the study of this phenomenon will fulfill its po- tential and provide accurate insights into the Weimar era. Ambitious psychoanalytic studies of Weimar film as well as general filmographies are useful sources on Wei- mar film, but the accessible works are also incomplete and even misleading. Theories about Weimar culture, about the group mind of Weimar, have been expounded, for example, which are based on limited rather than exhaustive studies of Weimar film. Yet these have nonetheless dominated the literature because no counter theories have been put forth. Both the deficiencies of the secondary literature and the nature of the topic under study--the film media--neces- sitate that attention be focused on the films themselves if the mysteries of the Weimar screenare to be untangled and accurately analyzed. Unfortunately the remnants of Weimar film available today are not perfectsources of information and not even firsthand accounts in othersour- ces on content and quality are reliable. However, these sources--the films and firsthand accounts of them--remain to be fully explored. They must be fully explored if the study of Weimar film is ever to advance. -

Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films

Gesticulated Shakespeare: Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Rebecca Collins, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Alan Woods, Advisor Janet Parrott Copyright by Jennifer Rebecca Collins 2011 Abstract The purpose of this study is to dissect the gesticulation used in the films made during the silent era that were adaptations of William Shakespeare's plays. In particular, this study investigates the use of nineteenth and twentieth century established gesture in the Shakespearean film adaptations from 1899-1922. The gestures described and illustrated by published gesture manuals are juxtaposed with at least one leading actor from each film. The research involves films from the experimental phase (1899-1907), the transitional phase (1908-1913), and the feature film phase (1912-1922). Specifically, the films are: King John (1899), Le Duel d'Hamlet (1900), La Diable et la Statue (1901), Duel Scene from Macbeth (1905), The Taming of the Shrew (1908), The Tempest (1908), A Midsummer Night's Dream (1909), Il Mercante di Venezia (1910), Re Lear (1910), Romeo Turns Bandit (1910), Twelfth Night (1910), A Winter's Tale (1910), Desdemona (1911), Richard III (1911), The Life and Death of King Richard III (1912), Romeo e Giulietta (1912), Cymbeline (1913), Hamlet (1913), King Lear (1916), Hamlet: Drama of Vengeance (1920), and Othello (1922). The gestures used by actors in the films are compared with Gilbert Austin's Chironomia or A Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery (1806), Henry Siddons' Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action; Adapted to The English Drama: From a Work on the Subject by M. -

Domestic Blitz: a Revisionist History of the Fifties

Domestic Blitz: A Revisionist History of the Fifties Gaile McGregor The fir st version of this paper was written for a 1990 conference at the University of Kansas entitled "Ikë s America." It was an interesting event—though flawed somewhat by the organizers' decision to schedule sessions and design program flow according to academic category. Eminently sensible from an administrative standpoint, this arrangement worked counter to the articulated aim of stimulating interdisciplinary dialogue by encouraging participants to spend all their time hanging out with birds of their own feather—economists with economists, historians with historians, literati with literati. Like many of the would-be innovative conferences, symposia, andevenfull-scale academic programsmounted over the last decade, this one was multi- rather than truly inter-disciplinary. This didn' t mean that I wasn t able to find any critical grist for my mill. Substantive aspects aside, the two things I found most intriguing about what I heard during those few days were, first, the number and variety of people who had recently "rediscovered" the fifties, and second, the extent to which the pattern of their rediscovery paralleled my own. Arriving there convinced I had made a major breakthrough in elucidating the darker and more complex feelings that undercolored the broadly presumed conservatism of the decade, what I heard over and over again from presenter s was the same (gleeful or earnest) revisions, the same sense of surprise at how much had been overlooked. Two messages might be taken from this. The first is that the fifties is suddenly relevant again. The second and perhaps more sobering concerns the mind-boggling power of 0026-3079/93/3401 -005$ 1.50/0 5 American culture to foster an almost complete collective amnesia about events and attitudes of the not-very-distant past. -

Bearing Witness to Female Trauma in Comics: An

BEARING WITNESS TO FEMALE TRAUMA IN COMICS: AN ANALYSIS OF WOMEN IN REFRIGERATORS By Lauren C. Watson, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Literature May 2018 Committee Members: Rebecca Bell-Metereau, Chair Rachel Romero Kathleen McClancy COPYRIGHT by Lauren C. Watson 2018 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Lauren C. Watson, refuse permission to copy in excess of the “Fair Use” exemption without my written permission. DEDICATION For my Great Aunt Vida, an artist and teacher, who was the star of her own story in an age when women were supporting characters. She was tough and kind, stingy and giving in equal measures. Vida Esta gave herself a middle name, because she could and always wanted one. Ms. Light was my first superheroine and she didn’t need super powers. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Three years ago, I woke up in the middle of the night with an idea for research that was daunting. This thesis is the beginning of bringing that idea to life. So many people helped me along the way. -

Murder on the Orient Express: a Return Ticket Wieland Schwanebeck

This is an accepted manuscript version of an article published in Adaptation 11.1 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1093/adaptation/apx025 Film Review: Murder on the Orient Express: A Return Ticket Wieland Schwanebeck Murder on the Orient Express. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Perf. Kenneth Branagh, Michelle Pfeiffer, Judi Dench, Johnny Depp. Fox, 2017. In the first scene of Kenneth Branagh’s big-screen adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express (1934)—one of Agatha Christie’s three most popular novels, according to a 2015 poll (Flood)—famous Belgian sleuth Hercule Poirot plagues the staff members of a Jerusalem hotel with his unusual request for two eggs of identical size. He goes so far as to apply a ruler to his breakfast, only to conclude that it does not meet his requirements. The scene serves as a neat summary of the character that will likely sit well with hardcore Christie admirers—the author famously had Captain Hastings characterize Poirot as a man so meticulous that ‘a speck of dust would have caused him more pain than a bullet wound’ (1920/2007: 14)—and the shot of Branagh (the film’s star as well as its director) cowering behind his breakfast table and scrutinizing the eggs sets up Murder on the Orient Express as an adaptation that literally goes ab ovo. It invokes the initial description of the character in Christie’s debut novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles (‘His head was exactly the shape of an egg’, 1920/2007: 14), and at the same time it is indicative of how the film reboots Christie for the twenty-first century, playing up Poirot’s tics while also humanizing him, an adaptive policy that has worked wonders for Sherlock Holmes.