New Theories of Cigarette Liability: the Restatement (Third) of Torts and the Viability of a Design Defect Cause of Action Alex J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT OF

Case 1:99-cv-02496-PLF Document 6276 Filed 08/03/18 Page 1 of 59 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ____________________________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) Plaintiff, ) Civil Action No. 99-CV-2496 (PLF) ) and ) ) CAMPAIGN FOR TOBACCO-FREE ) KIDS, et al., ) Plaintiff-Intervenors, ) ) v. ) ) PHILIP MORRIS USA INC., et al., ) Defendants. ) ) and ) ) ITG BRANDS, LLC, et al., ) Post-Judgment Parties ) Regarding Remedies ) PLAINTIFFS’ 2018 SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF ON RETAIL POINT OF SALE REMEDY TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 FACTUAL BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................... 5 I. The Deal between Cigarette Manufacturers and Retailers ............................................... 5 II. Benefits to Participating Retailers .................................................................................... 6 III. Manufacturers’ Contractual Control over Space for Cigarette Marketing and Promotional Displays ....................................................................................................... 8 A. The types of retail advertising and marketing space ........................................8 B. The manufacturers’ contractual authority over participating retailers’ space 10 1. The -

PM 12.31.2014 Form 10K Wrap (Incl F/S & MD&A)

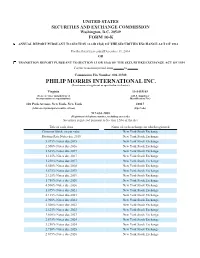

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2014 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-33708 PHILIP MORRIS INTERNATIONAL INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 13-3435103 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 120 Park Avenue, New York, New York 10017 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) 917-663-2000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, no par value New York Stock Exchange Floating Rate Notes due 2015 New York Stock Exchange 5.875% Notes due 2015 New York Stock Exchange 2.500% Notes due 2016 New York Stock Exchange 1.625% Notes due 2017 New York Stock Exchange 1.125% Notes due 2017 New York Stock Exchange 1.250% Notes due 2017 New York Stock Exchange 5.650% Notes due 2018 New York Stock Exchange 1.875% Notes due 2019 New York Stock Exchange 2.125% Notes due 2019 New York Stock Exchange 1.750% Notes due 2020 New York Stock Exchange 4.500% Notes due 2020 New York Stock Exchange 1.875% Notes due 2021 New York Stock Exchange 4.125% Notes due 2021 New York Stock Exchange 2.900% Notes due 2021 New York Stock Exchange -

Subject: ACCEPTED FORM TYPE 10-K (0001193125-12-076983) Date: 24-Feb-2012 09:29

Subject: ACCEPTED FORM TYPE 10-K (0001193125-12-076983) Date: 24-Feb-2012 09:29 THE FOLLOWING SUBMISSION HAS BEEN ACCEPTED BY THE U.S. SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION. COMPANY: Philip Morris International Inc. FORM TYPE: 10-K NUMBER OF DOCUMENTS: 17 RECEIVED DATE: 24-Feb-2012 09:28 ACCEPTED DATE: 24-Feb-2012 09:29 FILING DATE: 24-Feb-2012 09:28 TEST FILING: NO CONFIRMING COPY: NO ACCESSION NUMBER: 0001193125-12-076983 FILE NUMBER(S): 1. 001-33708 THE PASSWORD FOR LOGIN CIK 0001193125 WILL EXPIRE 09-Feb-2013 13:14. PLEASE REFER TO THE ACCESSION NUMBER LISTED ABOVE FOR FUTURE INQUIRIES. REGISTRANT(S): 1. CIK: 0001413329 COMPANY: Philip Morris International Inc. ACCELERATED FILER STATUS: LARGE ACCELERATED FILER FORM TYPE: 10-K FILE NUMBER(S): 1. 001-33708 24-Feb-2012 09:29 Page 1 of 1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ⌧ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2011 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-33708 PHILIP MORRIS INTERNATIONAL INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 13-3435103 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 120 Park Avenue, New York, New York 10017 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) 917-663-2000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered -

The SEC and the Failure of Federal, Takeover Regulation

Florida State University Law Review Volume 34 Issue 2 Article 2 2007 The SEC and the Failure of Federal, Takeover Regulation Steven M. Davidoff [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven M. Davidoff, The SEC and the Failure of Federal, Takeover Regulation, 34 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. (2007) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol34/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW THE SEC AND THE FAILURE OF FEDERAL TAKEOVER REGULATION Steven M. Davidoff VOLUME 34 WINTER 2007 NUMBER 2 Recommended citation: Steven M. Davidoff, The SEC and the Failure of Federal Takeover Regulation, 34 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 211 (2007). THE SEC AND THE FAILURE OF FEDERAL TAKEOVER REGULATION STEVEN M. DAVIDOFF* I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................. 211 II. THE GOLDEN AGE OF FEDERAL TAKEOVER REGULATION.................................. 215 A. The Williams Act (the 1960s) ..................................................................... 215 B. Going-Privates (the 1970s)......................................................................... 219 C. Hostile Takeovers (the 1980s)..................................................................... 224 1. SEC Legislative -

Altria Group, Inc. Annual Report

Altria Group, Inc. 2019 Annual Report an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company Howard A. Willard III Dear Fellow Shareholders Chairman of the Board and CEO Altria delivered solid performance in a dynamic year for the tobacco industry. Our core tobacco businesses delivered outstanding financial performance, and we made significant progress advancing our non-combustible product platform. We believe Altria’s enhanced business platform positions us well for future success. 2019 Highlights n Grew adjusted diluted earnings per share (EPS) by 5.8%, primarily driven by our core tobacco businesses; and types of legal cases pending against it, especially during the fourth n Achieved $600 million in annualized cost savings, exceeding our $575 quarter of the year. Altria recorded two impairment charges of our JUUL million target announced in December 2018; asset in 2019, reducing our investment to $4.2 billion at year-end, down from n Increased our regular quarterly dividend for the 54th time in 50 years $12.8 billion, our 2019 initial investment. JUUL remains the U.S. leader in the and paid shareholders approximately $6.1 billion in dividends; and e-vapor category, and in January 2020 we revised certain terms governing n Repurchased 16.5 million Altria shares for a total cost of $845 million. -

Altria Group, Inc. Annual Report

ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company | Inc. Altria Group, Report 2020 Annual an Altria Company From tobacco company To tobacco harm reduction company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company Altria Group, Inc. Altria Group, Inc. | 6601 W. Broad Street | Richmond, VA 23230-1723 | altria.com 2020 Annual Report Altria 2020 Annual Report | Andra Design Studio | Tuesday, February 2, 2021 9:00am Altria 2020 Annual Report | Andra Design Studio | Tuesday, February 2, 2021 9:00am Dear Fellow Shareholders March 11, 2021 Altria delivered outstanding results in 2020 and made steady progress toward our 10-Year Vision (Vision) despite the many challenges we faced. Our tobacco businesses were resilient and our employees rose to the challenge together to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, political and social unrest, and an uncertain economic outlook. Altria’s full-year adjusted diluted earnings per share (EPS) grew 3.6% driven primarily by strong performance of our tobacco businesses, and we increased our dividend for the 55th time in 51 years. Moving Beyond Smoking: Progress Toward Our 10-Year Vision Building on our long history of industry leadership, our Vision is to responsibly lead the transition of adult smokers to a non-combustible future. Altria is Moving Beyond Smoking and leading the way by taking actions to transition millions to potentially less harmful choices — a substantial opportunity for adult tobacco consumers 21+, Altria’s businesses, and society. To achieve our Vision, we are building a deep understanding of evolving adult tobacco consumer preferences, expanding awareness and availability of our non-combustible portfolio, and, when authorized by FDA, educating adult smokers about the benefits of switching to alternative products. -

1 CO-OPERATION AGREEMENT Dated As of 27 September 2010

CO-OPERATION AGREEMENT dated as of 27 September 2010 among IMPERIAL TOBACCO LIMITED AND THE EUROPEAN UNION REPRESENTED BY THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION AND EACH MEMBER STATE LISTED ON THE SIGNATURE PAGES HERETO 1 ARTICLE 1 DEFINITIONS Section 1.1. Definitions........................................................................................... 7 ARTICLE 2 ITL’S SALES AND DISTRIBUTION COMPLIANCE PRACTICES Section 2.1. ITL Policies and Code of Conduct.................................................... 12 Section 2.2. Certification of Compliance.............................................................. 12 Section 2.3 Acquisition of Other Tobacco Companies and New Manufacturing Facilities. .......................................................................................... 14 Section 2.4 Subsequent changes to Affiliates of ITL............................................ 14 ARTICLE 3 ANTI-CONTRABAND AND ANTI-COUNTERFEIT INITIATIVES Section 3.1. Anti-Contraband and Anti-Counterfeit Initiatives............................ 14 Section 3.2. Support for Anti-Contraband and Anti-Counterfeit Initiatives......... 14 ARTICLE 4 PAYMENTS TO SUPPORT THE ANTI-CONTRABAND AND ANTI-COUNTERFEIT COOPERATION ARTICLE 5 NOTIFICATION AND INSPECTION OF CONTRABAND AND COUNTERFEIT SEIZURES Section 5.1. Notice of Seizure. .............................................................................. 15 Section 5.2. Inspection of Seizures. ...................................................................... 16 Section 5.3. Determination of Seizures................................................................ -

Temporary Compliance Waiver Notice the Linked Files May Not Be Fully Accessible to Readers Using Assistive Technology

Temporary Compliance Waiver Notice The linked files may not be fully accessible to readers using assistive technology. We regret any inconvenience that this may cause our readers. In the event you are unable to read the documents or portions thereof, please email [email protected] or call 1-877-287-1373. Philip Morris Products S.A. THS Page 1 PMI Research & Development 2.7 Executive Summary MRTPA Section 2.7 Executive Summary Confidentiality Statement Confidentiality Statement: Data and information contained in this document are considered to constitute trade secrets and confidential commercial information, and the legal protections provided to such trade secrets and confidential information are hereby claimed under the applicable provisions of United States law. No part of this document may be publicly disclosed without the written consent of Philip Morris International. Philip Morris Products S.A. THS Page 2 PMI Research & Development 2.7 Executive Summary TABLE OF CONTENTS 2.7.1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................9 2.7.2 PROPOSED MODIFIED RISK AND MODIFIED EXPOSURE CLAIMS ........15 2.7.3 MODIFIED RISK TOBACCO PRODUCTS AND HARM REDUCTION .........17 2.7.4 PRODUCT DESCRIPTION AND SCIENTIFIC RATIONALE ..........................19 Development Rationale and Product Description for THS ............................................19 Heating Instead of Burning Reduces Harmful Constituents ......................................19 Product Description ...................................................................................................20 -

Complete Annual Report

Philip Morris International 2016 Annual Report THIS CHANGES EVERYTHING 2016 Philip Morris Annual Report_LCC/ANC Review Copy February 22 - Layout 2 We’ve built the world’s most successful cigarette company with the world’s most popular and iconic brands. Now we’ve made a dramatic decision. We’ve started building PMI’s future on breakthrough smoke-free products that are a much better choice than cigarette smoking. We’re investing to make these products the Philip Morris icons of the future. In these changing times, we’ve set a new course for the company. We’re going to lead a full-scale effort to ensure that smoke- free products replace cigarettes to the benefit of adult smokers, society, our company and our shareholders. Reduced-Risk Products - Our Product Platforms Heated Tobacco Products Products Without Tobacco Platform Platform 1 3 IQOS, using the consumables Platform 3 is based on HeatSticks or HEETS, acquired technology that features an electronic holder uses a chemical process to that heats tobacco rather Platform create a nicotine-containing than burning it, thereby 2 vapor. We are exploring two Platform creating a nicotine-containing routes for this platform: one 4 vapor with significantly fewer TEEPS uses a pressed with electronics and one harmful toxicants compared to carbon heat source that, once without. A city launch of the Products under this platform cigarette smoke. ignited, heats the tobacco product is planned in 2017. are e-vapor products – without burning it, to generate battery-powered devices a nicotine-containing vapor that produce an aerosol by with a reduction in harmful vaporizing a nicotine solution. -

Sales -- Implied Warranty -- Cigarette Manufacturer's Liability for Lung Cancer Henry S

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 42 | Number 2 Article 18 2-1-1964 Sales -- Implied Warranty -- Cigarette Manufacturer's Liability for Lung Cancer Henry S. Manning Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Henry S. Manning Jr., Sales -- Implied Warranty -- Cigarette Manufacturer's Liability for Lung Cancer, 42 N.C. L. Rev. 468 (1964). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol42/iss2/18 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 42 lingering, ominous cloud of illegality under the Robinson-Patman Act. JAMES M. TALLEY, JR. Sales-Implied Warranty-Cigarette Manufacturer's Liability for Lung Cancer Plaintiff's decedent initiated suit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida to recover damages for personal injuries resulting from lung cancer allegedly incurred by smoking Lucky Strike cigarettes. Shortly thereafter, he died from this condition and this claim1 was consolidated with another brought under the Florida wrongful death statute.' The district court sub- mitted the case to the jury on theories of negligence and breach of implied warranty.' In addition to rendering a general verdict for defendant, the jury answered specific interrogatories4 to the effect that the fatal lung cancer was proximately caused by the smoking of Lucky Strikes and that, as of the time of the discovery of the cancer, defendant could not by the reasonable application of human skill and foresight have known of the danger to users of his product. -

Chesterfield a T Naaiau St

HE EVENING WORLD, MONDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 1921. 10 EVENDAY RACING MEETING OPENS AT BOWIE TO-MORRO- W AL NORTON KNOCKS OUT Maryland Races Clinch THE FUSSY FOURSOME Hooking 'Em PAPKE IN SECOND ROUND, i Copyright. 1911. by the Press Publishing Co. (The .New York livening World. ' t t Norton. Yonker's undefeated wel- - Championship TTai, lei n . iKltt. who won twenty-ntn- o Titles for IF t madn't has , lookatuat! sttalght victories, added another victim -- .TllOl ax RIGHT HAND INTO THAT to Ida list last Saturday night at tha 1 Morvich and Exterminator so stronc? i'b op beem right on CoijiinontwalUi aporting Club when li'' kiHieked out Itanum liiliy l'apko In twi J -- I GREEN ! p bOM'T (JliRtL ) "That's what You feLUU THE. i rounds. It was n furious battle whilo !i lusted .mil I'.ipku col-ot- s ci since wciit down with Latter Displays His Remark- edit ho left Sun Urlar Court ME HOT. T' bo - AM' Look flying. I lu wan dropp.-- In tb nrsi last spring. Boveral trips to Kentucky gonna cjuit th'gamg. ! round for the count of nine nnd In tlm able Stamina in Winning ttom Maryland and Now York, and AT ME RIGHT ,jp To it ncoiid wild sent to the ennvns for the OH MV OiON CAM T --1 full count. Is looming up us many more to Canada. Alwny - HOOK EM -- FAUUT - I MEM , AM YOU HAb A Goob Norton fist a at Pimlico going and always willing, ho haH Tti PIN , YbU POCR SAP Jsek Hrltton's most dangerous contend- Saturday. -

EU Tobacco Products Directive 2014/40/EC

29.4.2014 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 127/1 I (Legislative acts) DIRECTIVES DIRECTIVE 2014/40/EU OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 3 April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, and in particular Articles 53(1), 62 and 114 thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the European Commission, After transmission of the draft legislative act to the national parliaments, Having regard to the opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee ( 1 ), Having regard to the opinion of the Committee of the Regions ( 2), Acting in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure ( 3 ), Whereas: (1) Directive 2001/37/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council ( 4) lays down rules at Union level concerning tobacco products. In order to reflect scientific, market and international developments, substantial changes to that Directive would be needed and it should therefore be repealed and replaced by a new Directive. (2) In its reports of 2005 and 2007 on the application of Directive 2001/37/EC the Commission identified areas in which further action was considered useful for the smooth functioning of the internal market. In 2008 and 2010 the Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR) provided scientific advice to the Commission on smokeless tobacco products and tobacco additives.