Programme Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OLLI June 2021 Environmental Conservation Heckel Study Group

June 2021 Study Group – OLLI - Biodiversity Collapse and 30x30 Overview: Our virtual study group will explore current data on global biodiversity collapse (sometimes called the Sixth Extinction) and major threats to wildlife and habitats in our first meeting. Our next three meetings will focus on potential solutions and how we can each support the proposed UN and US policies to conserve 30% of land and ocean by 2030. Optional film and reading resources are provided below. Week 1 – Wednesday, June 9th – 9:45am – 11am • Brief overview of the primary challenges facing the environment today – overconsumption, climate change, and biodiversity collapse. Discussion of the scope of these problems • Discussion of related challenges that make environmental conservation and pursuit of environmental sustainability difficult such as lack of awareness, lack of knowledge, not understanding what can be done, and disagreements within the ‘movement’ on priorities. Week 2 – Wednesday, June 16th – 9:45am – 11am • How individuals can impact the environment in their daily lives and local communities. • Why individual actions matter. • Example: Pollinator gardening Week 3 – Wednesday, June 23th – 9:45am – 11am • Class preparatory activity – 15-minute plastic audit • Opening – the complexity of consumption, the case of plastic • Some approaches to changing production and consumption o Consumer demand and advocacy o Business reform o Technological innovation o Government action – rewards and regulations Week 4 – Wednesday, June 30th – 9:45am – 11am • Some global (and national) movements o Paris Agreement o #30by#30 – Convention on Biological Diversity, China, Oct. 2021 o Global Plastic Treaty o International rights of nature • How can we support these efforts? • Study group conclusions – learning and engaging further 1 Recommended Resources: Note: these are a few recent resources on some of the topics we will cover in the class. -

Unity-With-Nature-Report-To-Repcom

Pacific Yearly Meeting Unity with Nature Committee Report to Representative Committee 2021 The Unity with Nature Committee (UwN) recognizes the need for bold and decisive action and inward transformation among Friends in response to the accelerating Holocene Extinction at the beginnings of the new millennium. The committee is setting up interest groups and online meetings to address these challenges—in particular, efforts are being made to set up an online Worship Group that will focus on the text of Braiding Sweetgrass, by Robin Wall Kimmerer, from a Quaker perspective for ecological and spiritual insight. Furthermore, the Committee is building: 1. UwN’s niche among other Quaker/Non-Quaker environmental organizations (FCLCA, FCNL, QEW, QIFF) 2. Methods of outreach to sense and respond to the work and needs of monthly meetings regarding environmental concerns. 3. Workshops/interest groups for Quarterly and Yearly Gatherings (and Online) on processing grief and finding courage in response to the climate crisis. 4. Endorsement and spreading awareness of the work of environmental organizations including but not limited to the UN Actions for Climate Empowerment (ACE) framework, Climate Literacy and Energy Awareness Network (CLEAN), Interfaith Power and Light, and the Romero Institute for enacting climate policy 5. Encouragement of all Friends to engage with the work of Robin Wall Kimmerer and the recent documentary/book A Life on Our Planet by David Attenborough. 6. Playing a role in supporting/facilitating/encouraging Quaker work in nonviolent activism and nonviolent direct action (NVDA) for protection of the living world. Braiding Sweetgrass Worship Group The Unity with Nature committee encourages Friends in Pacific Yearly Meeting to engage with the work of Robin Wall Kimmerer, an indigenous Anishinaabekwe ecologist who’s recent work Braiding Sweetgrass has made waves in environmentalist and religious circles alike. -

Halve Humanity's Footprint on Nature to Safeguard Our Future

HALVE HUMANITY’S FOOTPRINT ON NATURE TO SAFEGUARD OUR FUTURE AUGUST 2021 115 CALLING ON THE PARTIES TO THE CONVENTION CONTENTS ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY CALL TO ACTION 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 TO ADOPT A MILESTONE 1: THE PROBLEM - Earth’s Biodiversity is in Crisis 12 2: THE CAUSE - Humanity’s Footprint on Nature 16 TO HALVE THE FOOTPRINT 3: THE SOLUTION - A Nature-Positive World 22 4: THE OPPORTUNITY - Green Jobs, Better Living 30 OF PRODUCTION 5: THE PATH FORWARD 34 6: SECTOR OVERVIEW 38 AND CONSUMPTION ANNEX 42 ENDNOTES 44 BY 2030 AS PART OF THE POST-2020 GLOBAL BIODIVERSITY FRAMEWORK The report was written by Dalberg Advisors, and the team was comprised of Wijnand de Wit and Martin Freimüller. Editors Emily McCoy (WWF), Barney Jeffries Visual Designer Lou Clements Project Director Wijnand DeWit (Dalberg) The authors want to acknowledge the crucial contributions of WWF experts Lin Li, Gavin Edwards, Rebecca Shaw, Mark Wright, Martina Fleckenstein, Brent Loken, Innocent Maloba, Vishaish Uppal, Jean Timmers, Pauli Merriman, Tim Packeiser, Kate Newman, Colman O’Criodain, Elaine Geyer-Allély, Cristina Eghenter, Tobias Kind-Rieper, Kirsty Leong, Luca Chinotti and Guido Broekhoven. © GlobalP / Istockphoto CALL TO ACTION WWF CALLS ON STATES THAT ARE PARTY TO THE CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY (CBD) TO ADOPT A 2030 MILESTONE TO HALVE THE FOOTPRINT OF PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION IN THE POST-2020 GLOBAL BIODIVERSITY FRAMEWORK (GBF). Biodiversity loss comes at a price. Biodiversity is declining at alarming rates. This is already having serious negative impacts on food security, human health and economic output, which disproportionately fall onto the world’s poorest. -

November 2020

The Crystal Cover November 2020 y dream job post-college was to work The first day of each month I roam the park Mas an investigative reporter for 20/20. updating the bulletin boards with tide This was the 80’s and Geraldo Rivera was charts, calendars, event flyers etc. On the the industry rock star (of sensational first of October it was a sweltering day journalism anyways). On a recent and I felt like I was melting even in the Sunday segment of 60 Minutes early morning. Interestingly enough, I was reminded of this long- I saw and heard so many birds on ago aspiration while I watched my walk around Moro Campground in awe as reporter Anderson and the southern end of the park, Cooper interviewed Sir David and wondered why they were all Attenborough. This youthful so chipper? I was stupefied by such nonagenarian has been chronicling avian activity knowing that heat the natural world for decades starting and birds are not a good mix. For in the 1950’s with his groundbreaking one, they have layers of soft, downy BBC Series “Life On Earth,” and was feathers that provide them with warmth. as passionate and practical at 94 years Who needs warmth on a 90+ degree day, old as he was in those early day when his but more so, birds don’t perspire and have breathtaking footage and riveting descriptions a higher body temperature than that of humans (a from around the globe provided a look into a world that was Northern Cardinal, for example, has a core body heat of 106 entirely foreign, but exceedingly exciting. -

Action-Mag-Summer-2021.Pdf (Wwf.Org.Uk)

WIN CHARLIE MACKESY T-SHIRTS PAGE 30 THE MAGAZINE FOR WWF MEMBERS SUMMER 2021 HOPE FOR TIGERS Thanks to you, wild tigers are bouncing back. But they still need our help to thrive 10 WILDFLOWERS TO SPOT CALL OF THE WILD This summer, go on a wildflower We launch our new podcast series by chatting safari to discover 10 beautiful blooms to Sir David Attenborough about his that are rich in culture and folklore hopes and fears for the future CONTENTS Full of vibrant blooms and abuzz with insects, wildflower TOGETHER, WE DID IT! 4 WILDFLOWER GUIDE 24 meadows are a treat for all the A round-up of all you’ve helped Author Jonathan Drori celebrates senses in summer. Tragically, us achieve in recent months 10 of summer’s finest blooms 97% of these precious habitats have been lost over the years. So we’re working to fill the UK’s WWF IN ACTION 6 INTERVIEW: fields with flowers once more Environment news, including SIR DAVID ATTENBOROUGH 26 our Just Imagine competition WWF ambassador Cel Spellman launches our new Call of the Wild TIGERS BOUNCE BACK 10 podcast by chatting to his hero As wild tigers start to reclaim lost lands they once roamed, we need 60 YEARS OF WWF 28 your help to support the people Dave Lewis, chair of our trustees, who share their home and keep reveals his ambitions for WWF tiger numbers growing. and some of the ways you’re By Mike Unwin helping us make a difference BIG PICTURE 18 GIVEAWAYS 30 A mighty herd of wildebeest Win a Charlie Mackesy T-shirt in the Mara reminds us of the and Jana Reinhardt jewellery importance of protecting ancient wildlife migration routes CROSSWORD 31 Solve our crossword to win a MAGNIFICENT MEADOWS 20 copy of Restoring the Wild Join our exciting new campaign to restore and protect 20 million NOTES FROM THE FIELD 31 square feet of rare wildflower Rishi Kumar Sharma follows his meadows. -

News Arts Eats

NORTHERN SANTA BARBARA COUNTY’S NEWS AND ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY > NOVEMBER 5 - NOVEMBER 12, 2020 > VOL. 21 NO. 36 > WWW.SANTAMARIASUN.COM VISIT US ONLINE @santamariasun.com. SIGN UP for E-Newsletter(s) AT THE MOVIES LIKE US on Facebook FOLLOW US on Instagram FOLLOW US on Twitter 1 A Life on Our Planet: Grim truth [19] Santa Maria high schools attempt to address a much higher than ususal number of failing grades caused by distance learning [6] BY MALEA MARTIN Struggle to educate A local lawsuit about Pricey Diggs’ new Alisos Canyon NEWS political signs [4] ARTS Americana album [17] EATS becomes an AVA [20] NOVEMBER 5 - NOVEMBER 12, 2020 VOL. 21 NO. 36 Next Week! ith nearly four times as many failing grades on recent student progress reports as the same time last year, the Santa Maria Joint Union High School THE NTMA PUBLICATION WDistrict is looking at how to turn those grades around. Teachers told the Sun that while some students aren’t November 12, 2020 showing up to class or turning in work, others are just falling 2 behind due to the change in teaching style and homework PROGRESS? Santa Maria Joint Union High The issue will contain loads associated with distance learning during the COVID- School District’s recent student progress interviews with and photos 19 pandemic. Staff Writer Malea Martin talks to teachers, reports indicate that distance learning of the fi rst place winners; the parents, and students about what the issues are and what the isn’t going very well for many kids. second and third place winners future should look like [6]. -

October 2020 'Saving Ecuador's Chocó Forest'

#SaveTheChocó: Alliance formed to rescue natural wonder from ‘extinction cliff’ as Attenborough documentary issues plea for planet Days after WLT patron Sir David Attenborough showcased what human activities are doing to the planet, WLT launches campaign to help save the last 2% of Ecuador’s Chocó forest, home to critically endangered populations of Jaguar, Brown-headed Spider Monkey and many others. With support from WLT and others, Fundación Jocotoco will purchase and protect the largest tract of remaining Chocó forest from a single company, unlocking a Yosemite-sized, 740,000- acre chain of reserves from sea level to the Andes for wildlife to escape rising temperatures. Jocotoco’s plan is critical to avert the “extinction cliff” looming over the Chocó, a world- important forest home to the same reptile and amphibian diversity as the Amazon, more bird species than in the whole of Europe and the highest plant diversity of the Americas. MONDAY 5 OCTOBER 2020: World Land Trust (WLT) is rallying behind long-running partner Fundación Jocotoco (FJ) as they act to protect Ecuador's vanishing Chocó forests, a global alliance for a little-known biodiversity hotspot that follows Sir David Attenborough’s latest plea to save the natural world. Coinciding with the WLT patron’s warnings about natural destruction in the Netflix documentary ‘A Life on Our Planet’, WLT has launched a new fundraising appeal to back FJ as they purchase and protect the largest remaining tract of Chocó forest in Ecuador – a total of 57,000 acres of rainforest they will buy from a single company with support from WLT and other organisations. -

{DOWNLOAD} Extinction: a Radical History Ebook, Epub

EXTINCTION: A RADICAL HISTORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ashley Dawson | 130 pages | 22 Jul 2016 | Or Books | 9781944869014 | English | New York, United States Extinction by Ashley Dawson - OR Books Devouring their way down the food chain as they spread across the planet, they began a process of voracious extinction that has continued to the present. Headlines today are made by the existential threat confronting remaining large animals such as rhinos and pandas. But the devastation summoned by humans extends to humbler realms of creatures including beetles, bats and butterflies. Researchers generally agree that the current extinction rate is nothing short of catastrophic. Currently the earth is losing about a hundred species every day. Menu Resilience Building a world of resilient communities. Get Resilience delivered daily. Home Environment. Dawson makes unnecessary concessions to the idea that humans as a species are responsible for degradation of the environment, and he does this in some idealist as opposed to materialist terms. While he does explicitly argue against that point of view in a number of places, his early dating of the Anthropocene the new epoch defined by the dominance of human influence on earth systems weakens his argument, as does the lack of analysis of the difference between the complete alienation of workers from both the means of production and from nature under capitalism and the partial alienation present in earlier class societies. I would also like to see more discussion of the interrelationship of the different crises caused by capitalism. The economic, climate change and extinction crises affect each other and make each individual crisis worse. -

Our Top Climate Documentaries David Attenborough: a Life on Our Planet

Our top climate documentaries David Attenborough: A Life on Our Planet 1h23mins | 2020 | IMDb: 9.1 | Netflix At a glance With a broadcasting career spanning six decades, Attenborough has visited every continent on the globe capturing the natural world in all its beauty. He has also seen first-hand the negative impact humanity has had on nature. At 94 years old, this film serves as Attenborough’s witness statement, chronicling the destruction he has seen over his career, as well as sharing his vision for the future. 2040 1h30mins | 2019 | IMDb: 7.2 | YouTube, Google Play At a glance Follow director Damon Gameau as he explores what the year 2040 could look like if we rapidly bring the best of the already available climate crisis solutions into the mainstream. This film is structured as a visual letter to his four-year-old daughter, who will be 25 in 2040. Instead of telling you to go full vegan, he shows how we can combat climate change without emphasis on sacrifice. It’s an enjoyable watch that will leave you feeling optimistic about the future. Fire in Paradise 0h40mins | 2019 | IMDb: 7.4 | Netflix At a glance Survivors recount their harrowing stories from the 2018 Camp Fire, which destroyed the town of Paradise and became the deadliest wildfire in California history. Fire in Paradise is a difficult but must-watch. It’s a gut-wrenchingly tense and unflinching portrail of the severe stress felt by Paradise residents during the fire. Chasing Coral 1h33mins | 2017 | IMDb: 8.1 | Netflix At a glance This film shows how rising ocean temperatures are destroying coral reefs. -

Climate & Environmental Giving 2021

A Rising Tide Climate & Environmental Giving 2021 Report by Groundswell Giving and Australian Environmental Grantmakers Network A RISING TIDE - CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENTAL GIVING 2021 AND ENVIRONMENTAL A RISING TIDE - CLIMATE Table of Contents. 5 Introduction International 6 Trends Australian 7 Trends Changing Australian Attitudes Growth in Environmental Organisations A David vs Goliath Challenge Case Studies 13 Stephen Pfeiffer The Myer Foundation Clare Herschell Alan Schwartz AM Bella Wiggs Organisations 21 Supporting Climate & Environmental Giving Groundswell Australian Environmental Grantmakers Network Impatience Earth Conclusion 24 2 INTRODUCTION A RISING TIDE - CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENTAL GIVING 2021 AND ENVIRONMENTAL A RISING TIDE - CLIMATE “Right now, we’re facing a manmade disaster of global scale - our greatest threat in thousands of years. If we don’t take action, the collapse of our civilizations and the extinction of much of the natural world is on the horizon. But the longer we leave it, the more difficult it’ll be to do something about it” Sir David Attenborough, A Life on Our Planet 3 Acknowledgment of Country. Wherever we are in this country, we acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first inhabitants and the traditional custodians of the lands where we live, learn and work. We pay our respects to the Elders past and present, for they hold the memories, the traditions and culture. Authors. Anna Rose Co-founder, Groundswell Giving Bella Wiggs Engagement Strategist, Groundswell Giving Daisy Barham Environmental Philanthropy Manager, AEGN 4 INTRODUCTION A RISING TIDE - CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENTAL GIVING 2021 AND ENVIRONMENTAL A RISING TIDE - CLIMATE Introduction. Global acceptance of climate change, and the Increasingly, other grant makers are having the same fundamental impact it will have on our lives, is idea. -

A Life on Our Planet Summary

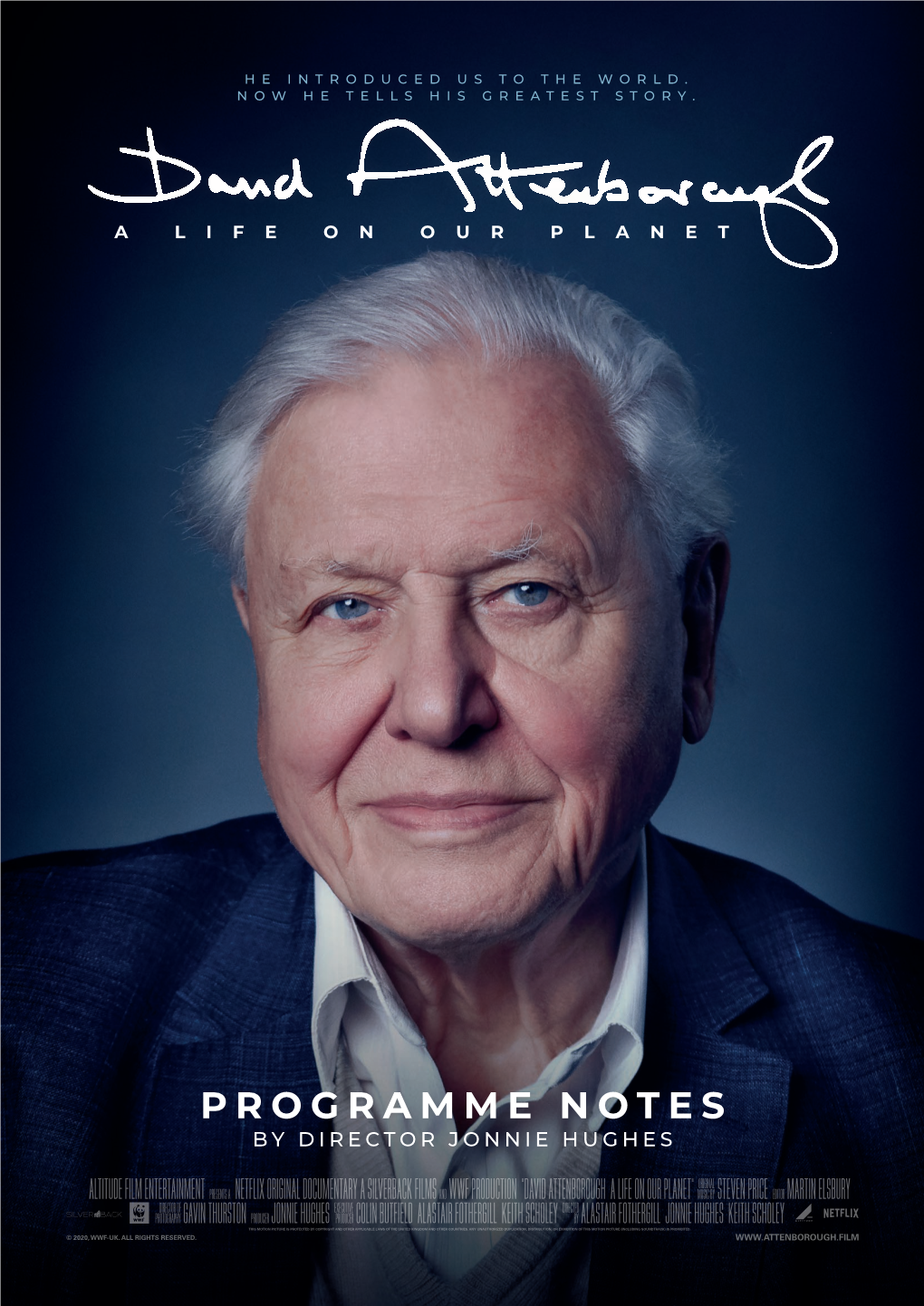

A Life on Our Planet Summary By David Attenborough We remember environmental disasters, but do we actually learn from them? In 2008, academic researcher Maxwell Boykoff, studied UK tabloids to determine how climate change was represented across the widest circulating newspapers. Environmental issues have historically had low news value. The purpose of Boykoff's study was to examine environmental representations, to 'provide opportunities to interrogate how particular narratives are translated, and how they make (in)visible certain discourses.' One of the significant findings was that we pay attention to the environment when it affects us. Hence, if we suffer the fallout of a natural disaster, we take notice of the planet. With this in mind, David Attenborough has dedicated his life to educating us about our planet, and making discourses visible, through his captivating storytelling. A Life on Our Planet is a masterpiece that explores the life and legacy of natural historian and national treasure David Attenborough. While the future of our planet may look bleak, Attenborough offers us hope and a vision for restoring our planet. Attenborough is famous for many of the truly epic natural history documentaries on our planet. His passion for protecting diverse wildlife, and reclaiming our wilderness is palpable, and A Life on Our Planet is his "witness statement." It's a statement of his past experiences, what will happen if our current destructive path continues, and what we need to do to rehabilitate our remarkable planet. Let's briefly go back in time. More recently, you may have heard of Pripyat from the HBO series Chernobyl? Overnight, Pripyat transformed from a pleasant, bustling town to a nightmarish disaster zone. -

Rewilding Is Life-Changing — It Saves Multiple Species

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2020 TIMES EVOKE NEW DELHI ‘Rewilding is life-changing — it saves multiple species and creates sustainable economies’ avid Attenborough’s new documentary teaches ecology and evolutionary biology at Princeton University. Closely involved ‘A Life On Our Planet’ is an extraordi- Robert Pringle A DREAM REALISED Dnary ‘witness statement’, where the in successful rewilding projects in Costa Rica and Mozambique, the biodiversity expert shares his From impalas to waterbuck, wildlife iconic naturalist describes both paradise lost numbers in Gorongosa National — and inspiration gained. Attenborough, who insights with Times Evoke on how these projects worked — and what they’ve brought back: Park have risen with rewilding has spent 70 years covering Earth’s species, traces nature’s story from the Holocene, 10,000 ewilding is important for the be if people cannot realise the benefits. 3 years ago, when all its living beings shared a future of humanity. And we One universal benefit is the opportunity veritable Garden of Eden. Nature, Attenbor- now need to decide what the to experience the place. Therefore, in Mo- 2 ough emphasises, means harmony, its diverse R quality of this future will be. zambique and Costa Rica, a major empha- beings composing ecosystems where each Will it be vibrant, invigorating and sis is on educational field trips for chil- 1 species contributes vital services. These in- healthy? Or will it be dreary and digital, dren, who will grow up to be the custodi- Animals/sq km Animals/sq clude dispersing seeds which become crops, sitting in our basements, vilifying each ans of protected areas.