Frogs Are Amphibians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pond-Breeding Amphibian Guild

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2015 Pond-breeding Amphibians Guild Primary Species: Flatwoods Salamander Ambystoma cingulatum Carolina Gopher Frog Rana capito capito Broad-Striped Dwarf Siren Pseudobranchus striatus striatus Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum Secondary Species: Upland Chorus Frog Pseudacris feriarum -Coastal Plain only Northern Cricket Frog Acris crepitans -Coastal Plain only Contributors (2005): Stephen Bennett and Kurt A. Buhlmann [SCDNR] Reviewed and Edited (2012): Stephen Bennett (SCDNR), Kurt A. Buhlmann (SREL), and Jeff Camper (Francis Marion University) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Descriptions This guild contains 4 primary species: the flatwoods salamander, Carolina gopher frog, dwarf siren, and tiger salamander; and 2 secondary species: upland chorus frog and northern cricket frog. Primary species are high priority species that are directly tied to a unifying feature or habitat. Secondary species are priority species that may occur in, or be related to, the unifying feature at some time in their life. The flatwoods salamander—in particular, the frosted flatwoods salamander— and tiger salamander are members of the family Ambystomatidae, the mole salamanders. Both species are large; the tiger salamander is the largest terrestrial salamander in the eastern United States. The Photo by SC DNR flatwoods salamander can reach lengths of 9 to 12 cm (3.5 to 4.7 in.) as an adult. This species is dark, ranging from black to dark brown with silver-white reticulated markings (Conant and Collins 1991; Martof et al. 1980). The tiger salamander can reach lengths of 18 to 20 cm (7.1 to 7.9 in.) as an adult; maximum size is approximately 30 cm (11.8 in.). -

National Recovery Plan for the Stuttering Frog Mixophyes Balbus

National Recovery Plan for the Stuttering Frog Mixophyes balbus David Hunter and Graeme Gillespie Prepared by David Hunter and Graeme Gillespie (Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria). Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) Melbourne, October 2011. © State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 978-1-74242-369-2 (online) This is a Recovery Plan prepared under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, with the assistance of funding provided by the Australian Government. This Recovery Plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Disclaimer: This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. An electronic version of this document is available on the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts website www.environment.gov.au For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre 136 186 Citation: Hunter, D. -

Status of Populations of Threatened Stream Frog Species in the Upper Catchment of the Styx River on the New England Tablelands, Near Sites Where Trout Releases Occur

Status of populations of threatened stream frog species in the upper catchment of the Styx River on the New England Tablelands, near sites where trout releases occur. Year 3: continuation of established transect monitoring for the study of trout impacts in endangered frog demographics. Simon Clulow, John Clulow & Michael Mahony School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle Prepared For Recreational Freshwater Fishing Trust New South Wales Department of Primary Industries October 2009 i Executive Summary The authors of this report were engaged to assess the status of populations of threatened stream frogs in and around the upper catchment of the Styx River on the New England Tablelands in areas where trout releases occur over the spring/summer periods of 2007/2008 and 2008/2009. The brief for this study required an assessment of the impact of introduced trout on these threatened frog populations in streams where trout have been released. The rationale for this study was the implication of trout in the decline of several Australian specialist stream breeding amphibian species in 1999 (Gillespie & Hero, 1999). Initial surveys of the region 2006 involved broad landscape scale surveys of the presence/absence of a number of threatened species that were known to be present in the New England Tablelands historically. In 2007 and 2008, the studies were focussed on a smaller number of permanent transects that were established at 11 sites in the Styx River area to investigate more intensely potential impacts of trout on two endangered frogs: the Glandular Frog, Litoria subglandulosa and the Stuttering Frog, Mixophyes balbus. -

Class: Amphibia Amphibians Order

CLASS: AMPHIBIA AMPHIBIANS ANNIELLIDAE (Legless Lizards & Allies) CLASS: AMPHIBIA AMPHIBIANS Anniella (Legless Lizards) ORDER: ANURA FROGS AND TOADS ___Silvery Legless Lizard .......................... DS,RI,UR – uD ORDER: ANURA FROGS AND TOADS BUFONIDAE (True Toad Family) BUFONIDAE (True Toad Family) ___Southern Alligator Lizard ............................ RI,DE – fD Bufo (True Toads) Suborder: SERPENTES SNAKES Bufo (True Toads) ___California (Western) Toad.............. AQ,DS,RI,UR – cN ___California (Western) Toad ............. AQ,DS,RI,UR – cN ANNIELLIDAE (Legless Lizards & Allies) Anniella ___Red-spotted Toad ...................................... AQ,DS - cN BOIDAE (Boas & Pythons) ___Red-spotted Toad ...................................... AQ,DS - cN (Legless Lizards) Charina (Rosy & Rubber Boas) ___Silvery Legless Lizard .......................... DS,RI,UR – uD HYLIDAE (Chorus Frog and Treefrog Family) ___Rosy Boa ............................................ DS,CH,RO – fN HYLIDAE (Chorus Frog and Treefrog Family) Pseudacris (Chorus Frogs) Pseudacris (Chorus Frogs) Suborder: SERPENTES SNAKES ___California Chorus Frog ............ AQ,DS,RI,DE,RO – cN COLUBRIDAE (Colubrid Snakes) ___California Chorus Frog ............ AQ,DS,RI,DE,RO – cN ___Pacific Chorus Frog ....................... AQ,DS,RI,DE – cN Arizona (Glossy Snakes) ___Pacific Chorus Frog ........................AQ,DS,RI,DE – cN BOIDAE (Boas & Pythons) ___Glossy Snake ........................................... DS,SA – cN Charina (Rosy & Rubber Boas) RANIDAE (True Frog Family) -

Frogs and Toads Defined

by Christopher A. Urban Chief, Natural Diversity Section Frogs and toads defined Frogs and toads are in the class Two of Pennsylvania’s most common toad and “Amphibia.” Amphibians have frog species are the eastern American toad backbones like mammals, but unlike mammals they cannot internally (Bufo americanus americanus) and the pickerel regulate their body temperature and frog (Rana palustris). These two species exemplify are therefore called “cold-blooded” (ectothermic) animals. This means the physical, behavioral, that the animal has to move ecological and habitat to warm or cool places to change its body tempera- similarities and ture to the appropriate differences in the comfort level. Another major difference frogs and toads of between amphibians and Pennsylvania. other animals is that amphibians can breathe through the skin on photo-Andrew L. Shiels L. photo-Andrew www.fish.state.pa.us Pennsylvania Angler & Boater • March-April 2005 15 land and absorb oxygen through the weeks in some species to 60 days in (plant-eating) beginning, they have skin while underwater. Unlike reptiles, others. Frogs can become fully now developed into insectivores amphibians lack claws and nails on their developed in 60 days, but many (insect-eaters). Then they leave the toes and fingers, and they have moist, species like the green frog and bullfrog water in search of food such as small permeable and glandular skin. Their can “overwinter” as tadpoles in the insects, spiders and other inverte- skin lacks scales or feathers. bottom of ponds and take up to two brates. Frogs and toads belong to the years to transform fully into adult Where they go in search of this amphibian order Anura. -

NMFS and USFWS Biological Assessment

LOS GATOS CREEK BRIDGE REPLACEMENT / SOUTH TERMINAL PHASE III PROJECT NMFS and USFWS Biological Assessment Prepared for Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board 1250 San Carlos Avenue P.O. Box 3006 San Carlos, California 94070-1306 and the Federal Transit Administration Region IX U.S. Department of Transportation 201 Mission Street Suite1650 San Francisco, CA 94105-1839 Prepared by HDR Engineering, Inc. 2379 Gateway Oaks Drive Suite 200 Sacramento, California 95833 August 2013 NMFS and USFWS Biological Assessment Prepared for Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board 1250 San Carlos Avenue P.O. Box 3006 San Carlos, California 94070-1306 and the Federal Transit Administration Region IX U.S. Department of Transportation 201 Mission Street Suite 1650 San Francisco, CA 94105-1839 Prepared by HDR Engineering, Inc. 2379 Gateway Oaks Drive, Suite 200 Sacramento, California 95833 August 2013 This page left blank intentionally. Summary The Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board (JPB) which operates the San Francisco Bay Area’s Caltrain passenger rail service proposes to replace the two-track railroad bridge that crosses Los Gatos Creek, in the City of San Jose, Santa Clara County, California. The Proposed Action is needed to address the structural deficiencies and safety issues of the Caltrain Los Gatos Creek railroad bridge to be consistent with the standards of safety and reliability required for public transit, to ensure that the bridge will continue to safely carry commuter rail service well into the future, and to improve operations at nearby San Jose Diridon Station and along the Caltrain rail line. This Biological Assessment (BA) has been prepared for the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and U.S. -

145-152 Zunika Amit.Pmd

Malays. Appl. Biol. (2018) 47(6): 145–152 ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY OF PARTIALLY PURIFIED PEPTIDES ISOLATED FROM THE SKIN SECRETIONS OF BORNEAN FROGS IN THE FAMILY OF RANIDAE MUNA SABRI1,2, ELIZABETH JEGA JENGGUT1, RAMLAH ZAINUDIN3 and ZUNIKA AMIT1* 1Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia 2Centre of PreUniversity Studies, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia 3Department of Zoology, Faculty of Resource Science and Technology, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia *E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 20 December 2018, Published online 31 December 2018 The emergence of drug resistant bacteria has now the head and neck of the frogs (Rollin-Smith et al., become a major public health problem worldwide 2002). Most AMPs are cationic in nature and share (Cohen, 2000; Kumarasamy et al., 2010; Sengupta a net positive charge at neutral pH with the high et al., 2013). WHO report (2017) on global content of hydrophobic residues and an amphipathic surveillance of antimicrobial resistance revealed a character (Galdiero et al., 2013; Power & Hancock, widespread development of resistance in both gram 2003). These characteristics allow the frog skin positive and gram negative bacteria which had peptides to kill bacteria through cell lysis by threatened millions of people worldwide. A rapid binding to negatively charged components of the increase in the number of drug-resistant bacteria bacterial membrane (Schadich et al., 2013). The and the incidence nosocomial infections pose a AMPs attract attention due to their effectiveness in challenge to conventional therapies using existing killing both gram-negative and gram-positive antibiotics, leading to the need in finding bacteria, without any of the undesirable effects of alternative microbicides to control these infections antibiotic resistance (Conlon and Sonnevand, 2011; (Lakshmaiah et al., 2015). -

Amphibious Arizona

AMPHIBIOUS ARIZONA Although Arizona is a pretty arid and dry state, Arizona is home to 26 different species of frogs and toads, 23 of which are considered indigenous, or native to the state. The Colorado River Toad Did you know? The State Amphibian is the Arizona Treefrog (Incilius alvarius) (Hyla wrightorum). The Colorado River Frogs have always been important to the Toad, also called the people of Arizona because the presence of frogs means that water is near. Many Sonoran Desert Toad, Native American people in Arizona use is a toad that is native frogs to symbolize water or rain and the to almost half of the sound of frogs signals monsoon season state of Arizona. These for Arizona. toads are among the All toads are frogs but not all frogs are toads. ©2006 Gary Nafis/ASDM Sonoran largest in the state, Frogs have smooth, slimy skin while toads Desert Digital Library look bumpy and drier. and only come out The Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Lithobates during the rainy season. They eat primarily beetles, chiricahuensis) is a threatened species. but are known to eat other insects and small They’re a “true frog,” which means that they vertebrates like other frogs and toads. The Colorado need access to water continuously. Livestock River Toad provides a lot of the music of summer grazing, urbanization, water diversion, and groundwater pumping all threaten the with their croaking, but they also make some people Chiricahua Leopard Frog. anxious: Colorado River Toads secrete a poison called a Think about it! bufotoxin, which is How do you think the growth of cities have highly toxic to cats impacted Arizona’s amphibians? and dogs. -

C:\Program Files\Adobe\Acrobat 4.0\Acrobat\Plug Ins\Openall

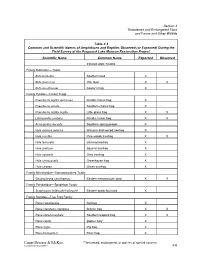

Section 4 Threatened and Endangered Flora and Fauna and Other Wildlife Table 4-3 Common and Scientific Names of Amphibians and Reptiles Observed (or Expected) During the Field Survey of the Proposed Lake Munson Restoration Project Scientific Name Common Name Expected Observed FROGS AND TOADS Family Bufonidae—Toads Bufo terrestris Southern toad X Bufo quercicus Oak toad X X Bufo woodhousei Fowler’s frog X Family Hylidae—Cricket Frogs Pseudacris nigrita verrucosa Florida chorus frog X Pseudacris ornata Southern chorus frog X Pseudacris nigrita nigrita Little grass frog X X Limnaoedus ocularis Florida cricket frog X X Acris gryllus dorsalis Southern spring peeper X Hyla avivoca avivoca Western bird-voiced treefrog X Hyla crucifer Pine woods treefrog X X Hyla femoralis Barking treefrog X Hyla gratiosa Squirrel treefrog X Hyla squirella Grey treefrog X Hyla chrysoscelis Greenhouse frog X Hyla cinerea Green treefrog X Family Microhylidae—Narrowmouthed Toads Gastrophryne carolinensis Eastern narrowmouth toad X X Family Pelobatidae—Spadefoot Toads Scaphiopus holbrookii holbrookii Eastern spadefoot toad X Family Ranidae—True Frog Family Rana catesbeiana Bullfrog X Rana clamitans clamitans Bronze frog X X Rana sphenocephala Southern leopard frog X X Rana capito gopher frog* X Rana grylio Pig frog X Rana heckscheri River frog X Camp Dresser & McKee *Threatened, endangered, or species of special concern s:\vandyke\lns\munson\t43 4-6 Section 4 Threatened and Endangered Flora and Fauna and Other Wildlife Table 4-3 Common and Scientific Names of Amphibians -

Conserving Reptiles and Frogs in the Forests of New South Wales

Please do not remove this page Conserving reptiles and frogs in the forests of New South Wales Newell, David A; Goldingay, Ross L https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/discovery/delivery/61SCU_INST:ResearchRepository/1266904610002368?l#1367373090002368 Newell, D. A., & Goldingay, R. L. (2004). Conserving reptiles and frogs in the forests of New South Wales. In Conservation of Australia’s forest fauna (pp. 270–296). Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales. https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/discovery/fulldisplay/alma991012820501502368/61SCU_INST:Research Repository Southern Cross University Research Portal: https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/discovery/search?vid=61SCU_INST:ResearchRepository [email protected] Open Downloaded On 2021/09/25 04:13:03 +1000 Please do not remove this page Conserving reptiles and frogs in the forests of New South Wales David Newell and Ross Goldingay* School of Environmental Science & Management, Southern Cross University, Lismore, 2480 NSW *Email: [email protected] The forests of New South Wales (NSW) contain a diverse fauna of frogs and reptiles (herpetofauna) with approximately 139 species occurring in forests and around 59 species that are forest-dependent. Prior to 1991, this fauna group received scant attention in research or forest management. However, legislative and policy changes in the early 1990s have largely reversed this situation. This review documents the changes in forest management that now require closer attention be given to the requirements of forest herpetofauna. We also provide an overview of research that contributes to a greater understanding of the management requirements of forest-dependent species. The introduction of the Endangered Fauna (Interim Protection) Act 1991 in NSW led to the need for comprehensive surveys of all forest vertebrate wildlife and detailed consideration of potential impacts on forest species listed as endangered by this Act. -

Chirp, Croak, and Snore

MINNESOTA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER Young Naturalists Teachers Guide Prepared by “Chirp, Croak, and Snore” Multidisciplinary Jack Judkins, Classroom Activities Curriculum Teachers guide for the Young Naturalists article “Chirp, Croak, and Snore” by Mary Hoff. Connections Published in the March–April 2014 Minnesota Conservation Volunteer, or visit www.dnr.state.mn.us/young_naturalists/frogs-and-toads-of-minnesota/index.html. Minnesota Young Naturalists teachers guides are provided free of charge to classroom teachers, parents, and students. This guide contains a brief summary of the article, suggested independent reading levels, word count, materials list, estimates of preparation and instructional time, academic standards applications, preview strategies and study questions overview, adaptations for special needs students, assessment options, extension activities, Web resources (including related Minnesota Conservation Volunteer articles), copy-ready study questions with answer key, and a copy-ready vocabulary sheet and vocabulary study cards. There is also a practice quiz (with answer key) in Minnesota Comprehensive Assessments format. Materials may be reproduced and/or modified to suit user needs. Users are encouraged to provide feedback through an online survey at www.mndnr.gov/education/teachers/activities/ynstudyguides/survey.html. *All Minnesota Conservation Volunteer articles published since 1940 are now online in searchable PDF format. Visit www.mndnr.gov/magazine and click on past issues. Summary “Chirp, Croak, and Snore” surveys -

Litoria Citropa)

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 803-808 (2021) (published online on 26 May 2021) Photo identification of individual Blue Mountains Tree Frogs (Litoria citropa) Jordann Crawford-Ash1,2,* and Jodi J.L. Rowley1,2 Abstract. We used a Photo Identification Method (PIM) to identify individuals of the Blue Mountains Tree Frog, Litoria citropa. By matching the body markings on photographs taken in the field of the lateral, dorsal and anterior views of the frog, we were able to re-match two individuals; one after 88 days and the other after 45 days. We present the first evidence that photo identification is likely to be a useful tool in individual recognition of L. citropa and is one of a few studies on the use of PIM in Australian frogs. Keywords. Body patterning, Australian frogs, non-invasive, mark recapture, individual recognition, PIM Introduction and utilised across multiple study periods (Auger-Méthé and Whitehead, 2007; Knox et al., 2013; Marlow et al., In a time of unprecedented rates of biodiversity decline, 2016). PIM has been particularly successful in studies of a good understanding of age structures, habitat use, cetaceans and mammals (Würsig and Jefferson, 1990; and population fluctuations is necessary for effective Auger-Méthé and Whitehead, 2007; Urian et al., 2015) ecological and conservation management strategies and is increasing in use for reptiles and amphibians (Phillott et al., 2007; Kenyon et al., 2009; Marlow et world-wide (Bradfield, 2004; Knox et al., 2013; Šukalo al., 2016). This information is often obtained through various sampling and survey methods such as mark- et al., 2013; Sacchi et al., 2016).