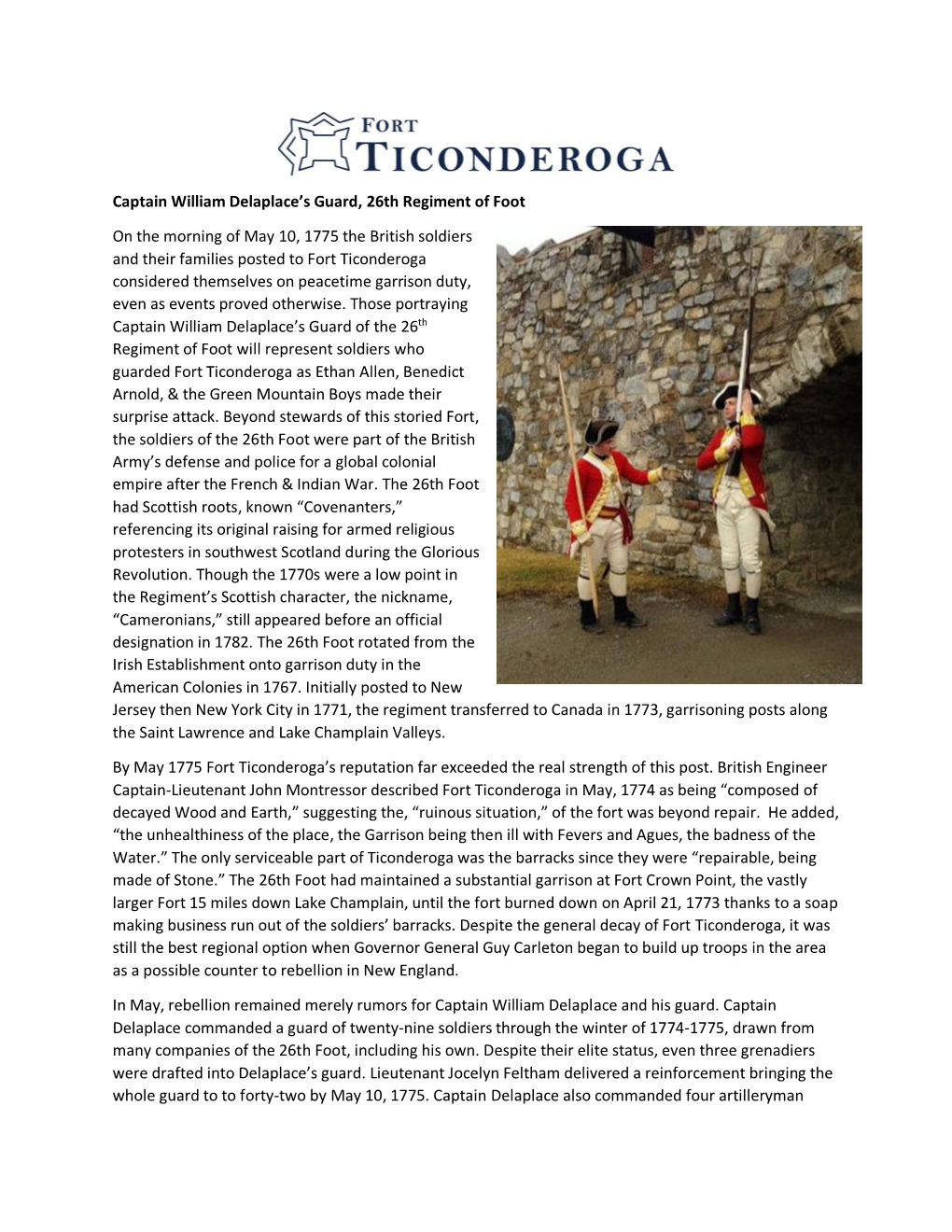

26Th Regiment of Foot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Marsh, 'A Rather Shadowy Figure

William Marsh, ‘a rather shadowy figure,’ crossed boundaries both national and political Vermont holds a unique but little-known place in eighteenth-century American and Canadian history. During the 1770s William Marsh and many others who had migrated from Connecticut and Massachusetts to take up lands granted by New Hampshire Governor Benning Wentworth, faced severe chal- lenges to their land titles because New York also claimed the area between the Connecticut and Hudson rivers, known as “the New Hampshire Grants.” New York’s aggressive pursuit of its claims generated strong political tensions and an- imosity. When the American Revolution began, the settlers on the Grants joined the patriot cause, expecting that a new national regime would counter New York and recognize their titles. During the war the American Continental Congress declined to deal with the New Hampshire settlers’ claims. When the Grants settlers then proposed to become a state separate from New York, the Congress denied them separate status. As a consequence, the New Hampshire grantees declared independence in 1777 and in 1778 constituted themselves as an independent republic named Vermont, which existed until 1791 when it became the 14th state in the Ameri- can Union. Most of the creators of Vermont played out their roles, and their lives ended in obscurity. Americans remember Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys and their military actions early in the Revolution. But Allen was a British captive during the critical years of Vermont’s formation, 1775-1778. A few oth- ers, some of them later Loyalists, laid the foundations for Vermont’s recognition and stability. -

TOURS 1. Ethan Allen: the Green Mountain Boys and the Arsenal

TOURS 1. Ethan Allen: The Green Mountain Boys and the Arsenal of the Revolution When the Green Mountain Boys—many of them Connecticut natives—heard about the Battles of Lexington and Concord, they jumped at the chance to attack the British Fort Ticonderoga in the despised state of New York. • Biographies o Benjamin Tallmadge (codename John Bolton) and the Culper Spy Ring o William Franklin, Loyalist Son of Benjamin Franklin o Seth Warner Leader of the Green Mountain Boys 2. Danbury Raid and the Forgotten General The British think they can land at the mouth of the Saugatuck River on Long Island Sound, rush inland, and destroy the Patriot’s supply depot in Danbury. They succeed, but at great cost thanks to the leadership of Benedict Arnold and General David Wooster. • Biographies o Sybil Ludington, the “Female Paul Revere” o Major General David Wooster o British General William Tyron 3. Israel Putnam and the Escape at Horse Neck Many of the most important military leaders of the American Revolution fought in the French and Indian War. Follow the life and exploits of one of those old veterans, Israel Putnam, as he leads his green Connecticut farmers against the mightiest military in the world. • Biographies and Boxes o General David Waterbury Jr. and Fort Stamford o The Winter Encampment at Redding, 1778-1779 o General David Humphreys o Loyalist Provincial Corp: Connecticut Tories 4. Side Tour: Farmer Put and the Wolf Den In 1742 Israel Putnam’s legend may have started when he killed the last wolf in Connecticut. © 2012 BICYCLETOURS.COM 5. -

Unofficial P.I.N

UNOFFICIAL P.I.N. 1805.81 SPECIAL NOTES LIST OF ADDITIONAL INSURED PARTIES Insurance provided to satisfy the requirements of Section 107-06 of the Standard Specifications shall be procured form insurance companies authorized to do such business in the States of New York and Vermont. The Contractor shall provide Protective Liability Insurance and Commercial General Liability Insurance to the following parties in accordance with Section 107-06.B of the Standard Specifications: New York Town of Crown Point, NY Lake Placid/Essex County Convention and Visitors Bureau (Lake Champlain Toll Keeper’s House / Lake Champlain Visitor Center) National Grid Crown Point Telephone Lake Champlain Transportation Co. (LCTC) Vermont State of Vermont (VT) Town of Addison, VT Green Mountain Power Corporation Waitsfield Telecom Cottonwood on Lake Champlain LLC (Vacation rental property) Page 1 of 1 UNOFFICIAL P.I.N. 1805.81 SPECIAL NOTES ADDITIONAL INFORMATION TO BE SUPPLIED BY AMENDMENT The Contractor is alerted to the fact that a large amendment will be issued prior to the contract letting. It is anticipated that this amendment will be made available on or about April 5, 2010. The following information is planned to be included in the amendment: Revised Summary of Quantities General Revisions and Clarifications of Details Final Cable Hanger Loads, Cable Lengths and Stressing Sequence Final Arch Span Post-Tensioning Sequence and Jacking Loads Pedestrian Railing Mesh Panel Details Electrical Drawings, Details and Schematics Lighting Details – Tie Girder Interior Maintenance Lighting; Arch Rib Aesthetic Lighting; Handrail Lighting Lake Work Zone Traffic Control Plan Page 1 of 1 UNOFFICIAL P.I.N. -

Fort Ticonderoga, New York - Site on a Revolutionary War Road Trip

Fort Ticonderoga, New York - Site on a Revolutionary War Road Trip http://revolutionaryday.com/usroute7/ticonderoga/default.htm Books US4 NY5 US7 US9 US9W US20 US60 US202 US221 Canal ETHAN ALLEN'S ROUTE TO TICONDEROGA Marker from Fort Ticonderoga When you arrive at Fort Ticonderoga, you step back in time. Fort Ticonderoga has been restored back to its original condition when the French first built the fort in 1755. To add to the realism, there are people dressed in period costume. There are also firing demonstrations and performances on the parade ground. There is always something going on to make a visit even more memorable. In the fort's museum, you will find personal possessions of many of the major players, such as Ethan Allen and John Brown. For example, there is Ethan Allen's gun with his name engraved on the stock that he lent to Benedict Arnold. There are also many maps, three-dimensional models, historical documents and revolutionary war art. 1 of 5 6/16/17, 4:54 PM Fort Ticonderoga, New York - Site on a Revolutionary War Road Trip http://revolutionaryday.com/usroute7/ticonderoga/default.htm Historic New York Fort Ticonderoga During the 18th century, when nations fought to control the strategic route between the St. Lawrence River in Canada and the Hudson River to the south, the fortification overlooking the outlet of Lake George into Lake Champlain was called "a key to continent." The French constructed here in 1755 the stronghold they named Carillon and made it a base to attack their English rivals. In 1758, Carillon, under Marquis de Montcalm, withstood assault by superior British Forces. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

il J NPS Form 10-900 Ç-y OMB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) •jpSËE^S United States Department of the Interior 1 MAR 1 7 2008 Rational Park Service • BY- National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each Item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested If an ilem does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable.' For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1, Name of Property historic name Lake Champlain Bridge other names/site number 2. Location street & number New York State Rt 903 not for publication Vermont State Rt 17 city or town Crown Point (NY) vicinity. Addison (VT) state New York code NY county Essex code 031 zip 12928 Vermont VT Addison 001 code 05491 3. State/Federal Agency Certification (Joint NY & VT) As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I certify that this [xT] nomination I [ request for determination of eligibility meets the.documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Ethan Allen (For Children)

Ethan Allen (For Children) Ethan was born in Litchfield, Connecticut on January 21 1738, the first child of Joseph and Mary Baker Allen. A few months later, Joseph removed his family to the brand-new town of Cornwall, Connecticut, where they lived a truly pioneer life among the steep and rocky hills through which the Housatonic River threaded its way toward Long Island Sound and the Atlantic Ocean. It was here that the young Ethan learned to cut trees, create fields, build stone walls and become a good hunter. In other words, all the skills that were required of pioneer children. When he was quite young, his parents realized that he was a very intelligent boy; he learned fast, and he asked untold questions. Schooling was never easily found in pioneer settlements; books were scarce, with usually only the Bible available in most homes. Fortunately for Ethan, his father was an intelligent man, and was able to give him what today would be called a “home education”. Joseph Allen hoped that Ethan would be able to attend Yale College in New Haven. At that time, Yale offered the best opportunity for a higher education in Connecticut. To prepare him for Yale, Ethan was sent to study with the Reverend Jonathan Lee in Salisbury, Connecticut. In a way, there is a Colebrook connection here: The Reverend Jonathan Lee had a son, named Chauncey, who became a minister in the Congregational Church, and eventually became Colebrook’s second minister in September, 1799. Reverend Lee remained in Colebrook more than 28 years. He lived in the house at the top of the hill north of Colebrook Center across from the cemetery. -

Crown Point Reservation Public Information Packet

Public Information Meeting Information Packet Crown Point Reservation Crown Point Campground and Day-Use Area, and Crown Point State Historic Site Unit Management Plan March 28, 2019 Crown Point, NY Information Packet Crown Point Reservation, Public Information Meeting March 28th, 2019; Crown Point Museum at Crown Point State Historic Site Agenda for Public Meeting March 28th, 6:00 PM Crown Point Museum 1. Open House 2. Welcoming Remarks 3. Overview of Crown Point Reservation and the Planning Process 4. Public Input Introduction NYS Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and NYS Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation (OPRHP) are working together to create a joint Unit Management Plan (UMP) for the Crown Point Reservation. The Crown Point Reservation consists of the Crown Point State Historic Site and the Crown Point Campground and Day-Use Area, totaling 440 acres. Since the underlying land is Forest Preserve, overall ownership, management and land use planning is that of the DEC. However, day to day management of the State Historic Site is the responsibility of OPRHP. The creation of a joint Unit Management Plan for Crown Point Reservation will allow for the highest protection of the site’s historic and natural resources and better facilitate public use and enjoyment of the entire area. DEC Agency Mission Statement To conserve, improve and protect New York's natural resources and environment and to prevent, abate and control water, land and air pollution, in order to enhance the health, safety and welfare of the people of the state and their overall economic and social well-being. OPRHP Agency Mission Statement The Mission of the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation is to provide safe and enjoyable recreational and interpretive opportunities for all New York State residents and visitors and to encourage responsible stewardship of our valuable natural, historic and cultural resources. -

Ethan Allen-The Soldier

Proceedings of the /7ERMONT Historical Society Montpelier /7ermont 1937 PVHS Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society 1 937 NEW SERIES Issued Quarterly VoL. V No. 1 ETHAN ALLEN-THE SOLDIER. AN ADDRESS By COLONEL LEONARD F. WING Colonel L eonard F . Wing and President John Spargo of the So ciety were the principal, speakers at the joint session of the Vermont Senate and House of R epresentatives held at the State House, Janu ary 21, 1937. The exercises were arranged by President Spargo in commemoration of the two hundredth anniversary of the birth of Ethan Allen on January 10, 1737. D etails of the program are given on pa-ge 34. Editor. · Mr. President, Your Excellency, Members of the General Assem bly, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen: AM not unmindful of the honor which you have conferred upon I me by the invitation to address you this evening upon the subject of Ethan Allen, the soldier. Within the short time allotted, those of you who have made a study of his military career can readily appre ciate that it will be impossible to deal extensively or in detail with his various military activities. There are, however, some incidents in his life concerning which I wish to refresh your recollection, that to my mind indicate his military ability, and establish without question or doubt his right to a high place among the military leaders of this Republic. First, we must have in mind the fact that Ethan Allen was not a professional soldier trained in the calling of arms; that his military knowledge, strategy and tactics were obtained in the hard school of CsJ experience and under conditions that at all times were most hazard ous and trying. -

The Capture of Fort Ticonderoga, Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold Are Engaged in a Heated Contest to See Who Would Ultimately Take Com- Mand of the Captured Fort

Background Information for Teachers Much of what we know about the historic capture of Fort Ticonderoga by Ethan Allen, Benedict Arnold, and the Green Mountain Boys on May 10, 1775, comes from the letters, journals, and diaries of the par- ticipants. This activity for students includes descriptions of the capture from the point of view of three men: Ethan Allen, Benedict Arnold, and Joceyln Feltham. Even though all three were present during the capture, their accounts don’t always agree. History is not a list of facts; it is the interpretation of facts. These three men each have a bias and rea- sons for including or excluding certain facts. In the hours and days after the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold are engaged in a heated contest to see who would ultimately take com- mand of the captured Fort. In the dozens of letter Ethan Allen writes in the days after May 10th, Benedict Arnold is only mentioned in one—the letter written to the New York Committee of Safety. Why? There was a warrant for Allen’s arrest in New York, and it was to Allen’s advantage, in that one letter, that his actions in capturing the fort not be seen as by his action alone. On the other hand, Jocelyn Feltham, second in command of the British troops at Ticonderoga, is writing a report to General Thomas Gage, the Commander-in-Chief of all British forces in North America. Feltham doesn’t care whether Allen or Arnold is in charge. His chief motivation is to defend his actions and those of his commander, Captain William Delaplace. -

US Route 7, Revolutionary War, History-Based Travel, Road Trip Drivin

US Route 7, Revolutionary War, History-based Travel, Road Trip Drivin... http://revolutionaryday.com/usroute7/default.htm Books US4 NY5 Home US9 US9W US20 US60 US202 US221 Canal TRIP LOG INTRODUCTION: A Revolutionary Day that follows the 1775 capture of Fort Ticonderoga. Early Morning -- Mile Mark 0-34.9 PITTSFIELD, MA: On May 1st, 1775 at Easton's Tavern, Edward Mott of Connecticut, John Brown and James Easton of Pittsfield met here to begin planning the first offensive military action against the British -- the capture of Fort Ticonderoga. WILLIAMSTOWN, MA: Pass through the home of Williams College, which was also a recruiting stop in 1775 and 1777. Mid-Morning -- Mile Mark 34.9-63.8 OLD BENNINGTON, VT: On the May 3rd, 1775 at the Catamount Inn, Ethan Allen met with Edward Mott, John Brown and James Easton to discuss the capture of Fort Ticonderoga. Two years later, Bennington's abundant storehouses would be an unsuccessful target of Burgoyne's British invasion from Canada. BENNINGTON BATTLEFIELD, NY: Visit the hilltop where British Forces, consisting mostly of mercenary Hessians under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Friedrick Baum, were surrounded and engaged by American Forces from New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Vermont. The British Forces surrendered on August 16, 1777. Late Morning -- Mile Mark 63.8-116.0 ARLINGTON, VT: In 1775, Arlington was a crossroad to a small advancing American army going to Fort Ticonderoga. 1 of 3 6/29/17, 9:56 AM US Route 7, Revolutionary War, History-based Travel, Road Trip Drivin... http://revolutionaryday.com/usroute7/default.htm MANCHESTER, VT: In 1775, Manchester was a crossroad to Fort Ticonderoga, but also a crossroad to a much larger American army, this one in retreat in 1777. -

Hubbardton Battlefield Research

Hubbardton Battlefield STORY OF THE BATTLE Hubbardton Battlefield is nationally significant as the site of an important military encounter during the Northern Campaign of 1777, and a formative event in the development of the Northern Department Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. A tactical loss for the American forces, historians conclude that, strategically, the battle was an American success because it allowed General St. Clair's withdrawing Northern Army to unite with General Schuyler’s forces near Fort Edward on 12 July, thus keeping alive the American army that blocked further movement south by British General John Burgoyne. The battle lasted more than three hours, probably closer to five, and involved soldiers from Vermont, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire. Several important Americans participated in the engagement, including Colonel Seth Warner of Vermont, and Colonel Ebenezer Francis of Massachusetts. Brigadier General Simon Fraser of the British 24th Regiment of Foot commanded the Advance Guard, while Baron Riedesel commanded the Royal Army’s Left Wing composed principally of Brunswick formations. The significance of this site is materially enhanced by the high integrity of its natural, cultural, and visual landscape as well as its archeological potential to improve upon or even radically change site interpretation. Archeological surveys conducted on the battlefield in 2001 and 2002 confirmed the presence of battle-related artifacts, such as lead shot, buttons, buckles, and other detritus of war. The Hubbardton Battlefield is an example of early attempts to preserve, and commemorate Revolutionary War battlefields, with a local grassroots effort that included veterans and eyewitnesses to the event. This initial mid-nineteenth-century effort was followed by official state involvement in the acquisition, development, and management of the site in the second quarter of the twentieth century as a historic site. -

United States Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE. WASHINGTON, D.C. 20240 IN REPLY REFER TO: MAR 3 1 1971 H30-HR Mr, William B. Pinney State Liaison Officer Board of Historic Sites 7 Langdon Street Montpelier, Vermont 05602 Dear Mr. Pinney» We are pleased to inform you that the historic properties listed on the enclosure have been placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Senators Winston L. Prouty and George D. Aiken and Representative Robert T. Stafford are being informed, A leaflet explaining the National Register is enclosed for each of the property owners, Please withhold any publicity on this until you have received a carbon copy of the Congressional correspondence, Sincerely yours (Signed.) Director Enclosures MAR 0 1 1971 Entered in the National Register Properties added to the National Register of Historic Places VERMONT Bennington Battle Monument Bennington County Bennington, Vermont Chimney Point Tavern Addison County Addison, Vermont Old Schoolhouse Bridge Caledonia County Lyndon, Vermont Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Vermont NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Addison INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY EN TRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) [1. NAME- Chimney Point Tavern AND/OR HISTORIC: |2. LOCATION STREET ANC NUMBER: State. Rte 125 CITY OR TOWN: Addison STATE CODE ^ Vermont Addison 001 13- CLASSIFICATÌON CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE t/> OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC • District gQ Building EKPubüc Public Acquisition: [~1 Occupied Yes: • Site • Structure I I Private I I In Process I I Unoccupied (/§ Restricted • Both j | Being Considered I I Unrestricted • Object ¡3 Preservation work in progress • No o PRESENT USE (Check One or More a : Appropriate,) I I Agricultural I I Government • Pork I I Transportation ! I Comments CÉ 'I I Commercial I I Industrial I I Private Residence • Other (Specify) EH Educational • Military I I Religious To be res tored 13th H r I I Entertainment I ^ Museum [~l Scientific century tavern </> Z f4.