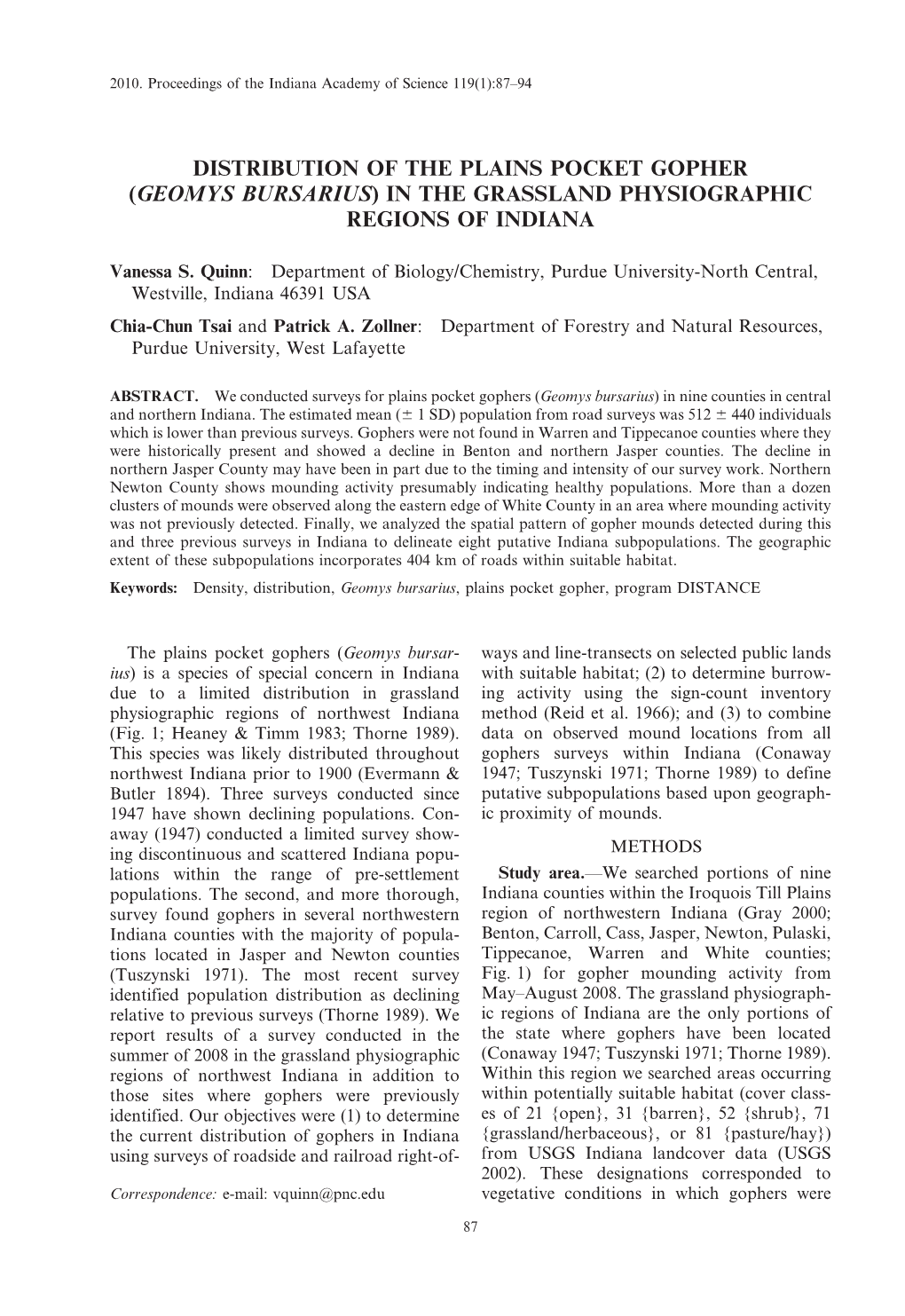

Geomys Bursarius) in the Grassland Physiographic Regions of Indiana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantifying Exposure of Wyoming's Wildlife To

QUANTIFYING EXPOSURE OF WYOMING’S WILDLIFE TO ENERGY DEVELOPMENT IN THE F ACE OF EXPANDING PRODUCTION Prepared by Douglas Keinath1 and Matthew Kauffman2 1 Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, 1000 E. University Ave., Dept. 3381, Laramie, Wyoming 82071 USA; E-mail: [email protected] 2 U.S. Geological Survey, Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Department of Zoology and Physiology, University of Wyoming, 1000 E. University Ave., Dept. 3166, Laramie, Wyoming 82071, USA; E-mail: [email protected] December 30, 2014 Suggested citation for this report: Keinath, D. and M. Kauffman. 2014. Quantifying exposure of Wyoming’s wildlife to energy development in the face of expanding production. Report prepared by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, Laramie Wyoming and Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, Cheyenne, Wyoming and the U.S. Geological Survey, Fort Collins, Colorado. December 30, 2014. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures ..................................................................................................................... 3 Summary ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Methods ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Amphibian Biodiversity Recovery in a Large-Scale Ecosystem Restoration

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 1(2):101-108 Submitted: 10 May 2006; Accepted: 12 November 2006 AMPHIBIAN BIODIVERSITY RECOVERY IN A LARGE-SCALE ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION 1,2 1 1 3 ROBERT BRODMAN , MICHAEL PARRISH , HEIDI KRAUS AND SPENCER CORTWRIGHT 1Biology Department, Saint Joseph’s College, Rensselaer, Indiana, 47978, USA 2Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] 3Biology Department, Indiana University Northwest, Gary, Indiana, 46408 USA. Abstract.—Amphibians are important components of ecosystem function and processes; however, many populations have declined due to habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation. We studied the effect of wetlands ecosystem restoration on amphibian population recovery at Kankakee Sands in northwest Indiana, USA. We also tested predictions about colonization in relation to proximity to existing nature preserves and species characteristics. Prior to restoration activities (1998), the amphibian community at Kankakee Sands consisted of fourteen populations of seven species at seven breeding sites. By 2001, this community increased to 60 populations at 26 sites; however, species richness had not increased. By 2002 the community increased to 143 populations of eight species at 38 sites, and by 2003 there were 172 populations of ten species at 44 sites. Abundance index values increased 15-fold from 1998-2003. These increases best fit the exponential growth model. Although survival through metamorphosis was substantial during wetter than average years (2002 and 2003), during other years restored wetlands dried before larvae of most species transformed. Amphibian colonization was greatest near a nature preserve with the greatest amphibian diversity. The earliest colonists included fossorial species and those species whose habitat includes wet and mesic sand prairie. -

Lasalle Fish & Wildlife Area's Hardwood Forests, Fields And

LaSalle Fish & Wildlife Area’s hardwood forests, fields and marshes were once part of Grand Kankakee Marsh. 20 July/August 2017 EVERGLADES MINUS THE GATORS Telling the Grand Kankakee Marsh story helps restore it OutdoorIndiana.org 21 Quis eos voloreperion ped quam qui te eumenis am cone officidebis mos estis volut officitata imusdae vernatem quam, (Top, bottom) Eastern prickly pear (Opuntia humifusa), a cactus found at Kankakee Sands, is attractive, useful and edible; it also serves as food and cover for wildlife. Black-eyed Susan and tall grasses flourish at Kankakee Sands, which was once part of Grand Kankakee Marsh; the area packs a vast array of plants and wildlife in its more than 7,000 acres. 22 July/August 2017 By Nick Werner, OI staff To this day, many do not know of the marsh, let alone its Photography by Frank Oliver importance. Even some of the re-enactors who attend Aukiki are unaware, Hodson said. But a century later, the Kankakee’s story is rising from the ground like a ghost in a cemetery, searching for answers about fter the downpour ceased, four its demise. The spirit of the marsh has benefited from cold- women in bonnets and long case conservationists like Hodson. Archaeologists, farmers, dresses sang frontier-era folk hunters and even filmmakers have also played a role. Togeth- er, they are re-examining the region’s history, hoping to cor- songs in French. rect past mistakes. Their methods include creation of public Do they know? John Hodson wondered. A awareness, as well as land preservation, wetland restoration Probably not, he decided. -

Louisiana's Animal Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN)

Louisiana's Animal Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) ‐ Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Animals ‐ 2020 MOLLUSKS Common Name Scientific Name G‐Rank S‐Rank Federal Status State Status Mucket Actinonaias ligamentina G5 S1 Rayed Creekshell Anodontoides radiatus G3 S2 Western Fanshell Cyprogenia aberti G2G3Q SH Butterfly Ellipsaria lineolata G4G5 S1 Elephant‐ear Elliptio crassidens G5 S3 Spike Elliptio dilatata G5 S2S3 Texas Pigtoe Fusconaia askewi G2G3 S3 Ebonyshell Fusconaia ebena G4G5 S3 Round Pearlshell Glebula rotundata G4G5 S4 Pink Mucket Lampsilis abrupta G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Plain Pocketbook Lampsilis cardium G5 S1 Southern Pocketbook Lampsilis ornata G5 S3 Sandbank Pocketbook Lampsilis satura G2 S2 Fatmucket Lampsilis siliquoidea G5 S2 White Heelsplitter Lasmigona complanata G5 S1 Black Sandshell Ligumia recta G4G5 S1 Louisiana Pearlshell Margaritifera hembeli G1 S1 Threatened Threatened Southern Hickorynut Obovaria jacksoniana G2 S1S2 Hickorynut Obovaria olivaria G4 S1 Alabama Hickorynut Obovaria unicolor G3 S1 Mississippi Pigtoe Pleurobema beadleianum G3 S2 Louisiana Pigtoe Pleurobema riddellii G1G2 S1S2 Pyramid Pigtoe Pleurobema rubrum G2G3 S2 Texas Heelsplitter Potamilus amphichaenus G1G2 SH Fat Pocketbook Potamilus capax G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Inflated Heelsplitter Potamilus inflatus G1G2Q S1 Threatened Threatened Ouachita Kidneyshell Ptychobranchus occidentalis G3G4 S1 Rabbitsfoot Quadrula cylindrica G3G4 S1 Threatened Threatened Monkeyface Quadrula metanevra G4 S1 Southern Creekmussel Strophitus subvexus -

Pocket Gophers Habitat Modification

Summary of Damage Prevention and Control Methods POCKET GOPHERS HABITAT MODIFICATION Rotate to annual crops Apply herbicides to control tap‐rooted plants for 2 consecutive years Flood land Rotate or cover crop with grasses, grains, or other fibrous‐rooted plants EXCLUSION Figure 1. Plains pocket gopher. Photo by Ron Case. Small wire‐mesh fences may provide protection for ornamental trees and shrubs or flower beds Plastic netting to protect seedlings Protect pipes and underground cables with pipes at least 3 inches in diameter or surround them with 6 to 8 inches of coarse gravel. FRIGHTENING Nothing effective REPELLENTS None practical Figure 2. Pocket gophers get their name from the pouches TOXICANTS on the sides of their head. Image by PCWD. Zinc phosphide Chlorophacinone OBJECTIVES 1. Describe basic pocket gopher biology and FUMIGANTS behavior 2. Identify pocket gopher signs Aluminum phosphide and gas cartridges 3. Explain different methods to control pocket gophers SHOOTING white, but generally align with soil coloration. The great variability in size and color of pocket gophers is Not practical attributed to their low dispersal rate and limited gene flow, resulting in adaptations to local TRAPPING conditions. Thirty‐five species of pocket gophers, represented by Various specialized body‐grip traps 5 genera occupy the western hemisphere. Fourteen Baited box traps species and 3 genera exist in the US. The major features differentiating these genera are the size of SPECIES PROFILE their forefeet, claws, and front surfaces of their chisel‐like incisors. Southeastern pocket gopher (Geomys pinetis) is the only species occurring in IDENTIFICATION Alabama. Pocket gophers are so named because they have fur‐ Geomys (Figure 3) have 2 grooves on each upper lined pouches outside of the mouth, one on each incisor and large forefeet and claws. -

Sand Hills Pocket Gopher Geomys Lutescens

Wyoming Species Account Sand Hills Pocket Gopher Geomys lutescens REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: No special status USFS R2: No special status USFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: No special status State of Wyoming: Nongame Wildlife CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: No special status WGFD: NSS3 (Bb), Tier II WYNDD: G3, S1S3 Wyoming Contribution: HIGH IUCN: Least Concern STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS Sand Hills Pocket Gopher (Geomys lutescens) is assigned a range of state conservation ranks by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database due to uncertainty concerning its abundance in Wyoming and lack of information on population trends in the state. Also, note that the Global rank (G3) is provisional at this time – NatureServe (Arlington, Virginia) has not yet formalized a Global rank for this species. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: Sand Hills Pocket Gopher was formerly considered a subspecies of Plains Pocket Gopher (G. bursarius) and given the sub-specific designation G. b. lutescens 1. It is now considered a full species based on a combination of genetic information and morphology 2 . Though two subspecies of G. lutescens have been suggested, none are widely recognized 3. It is suspected to hybridize with G. bursarius in some localities 4. Description: Like all pocket gophers, Sand Hills Pocket Gopher is adapted to fossorial life with large foreclaws, a heavy skull, strong jaw muscles, and relatively inconspicuous ears and eyes. It is similar in general appearance to the formerly synonymous G. bursarius, which has a sparsely- haired tail and relatively short pelage that can vary substantially in color from buff to black 5. However, G. lutescens is somewhat smaller and lighter in pelage color than G. -

Kankakee Sands Ornate Box Turtle (Terrapene Ornata) Population & Ecosystem Assessment

I LLINOI S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. Kankakee Sands Ornate Box Turtle (Terrapene ornata) Population & Ecosystem Assessment Final Report Illinois Natural History Survey Center for Biodiversity Technical Report No. 2003 (35) Submitted in Fulfillment of Requirements of Wildlife Preservation Fund Grant: IDNR RC03L21W And The Nature Conservancy Grant: Nature Conserv 1131626100 4 December 2003 Christopher A. Phillips, Andrew R. Kuhns, and Timothy Hunkapiller Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 E.Peabody Drive, Champaign, IL 61820 Introduction The Kankakee Sands Macrosite is a complex of high-quality natural lands including wet/mesic sand prairie, oak barrens/savanna, and sedge meadows in northeast Illinois and northwest Indiana. A project is currently underway which targets over 7,500 acres of cropland and degraded grassland/savanna for restoration into a mosaic of native grasslands, savannas and wetlands which will ultimately restore connectivity to a landscape-scale system exceeding 40,000 acres. The Nature Conservancy, with assistance from professionals from IL DNR, IN DNR, INHS, and state universities, is in the process of completing a viability study for the Kankakee Sands Macrosite. One of the target species in the ornate box turtle (Terrapene ornata). It is easy to see why the ornate box turtle is considered a target species of sand prairies and savannas of the Kankakee Sands ecosystem. The turtle is associated with open habitats characterized by rolling topography with grasses and low shrubs as the dominant vegetation. Disturbance factors such as fire, grazing, and the presence of plains pocket gopher maintain the open structure of prairie and savannas which benefit the turtle. -

VERTEBRATE ASSOCIATES of BLACK-TAILED PRAIRIE DOGS in OKLAHOMA 41 Vertebrate Associates of Black-Tailed Prairie Dogs in Oklahoma

VERTEBRATE ASSOCIATES OF BLACK-TAILED PRAIRIE DOGS IN OKLAHOMA 41 Vertebrate Associates of Black-Tailed Prairie Dogs in Oklahoma Jack D. Tyler Department of Biology, Cameron University, Lawton, OK 73505 John S. Shackford 429 E. Oak Cliff Drive, Edmond, OK 73034 During surveys of black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) towns in Oklahoma in 1966-1967 and 1986-1989, 72 vertebrate associates were regularly encountered as well as 25 others that were found less often. The status of several species had apparently changed during this 23-year interval. Six avian species appeared to have increased in number, but declines in populations of seven other birds, five mammals, and one reptile were indicated. ©2002 Oklahoma Academy of Science INTRODUCTION The black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys afield at all seasons except during severe ludovicianus) originally ranged throughout cold spells, when prairie dogs were inactive. western Oklahoma (1,2). During the first We used several methods in attempting half of the 20th century, however, land- to locate Black-footed ferrets (Mustela owners eradicated most of the colonies, nigripes). These included examining prairie precipitating a drastic decline in prairie dog dog burrows for “trenching” (a ferret activity) numbers from millions [Bailey (1) estimated in winter,”“squeaking” while spotlighting at 800 million in Texas alone in 1905] to only a night, and inspecting unused irrigation pipes few thousand. The objectives of this study stacked near dogtowns with the aid of a were to document the occurrence of verte- flashlight. However, we found no evidence brate species found in Oklahoma prairie dog of this rare species in Oklahoma. -

Curriculum Vita Kenneth T

CURRICULUM VITA KENNETH T. WILKINS Personal Faculty office: Department of Biology, Baylor University, Waco, Texas 76798-7388 (254) 710-2911, FAX: (254) 710-2969 Administrative office: Graduate School, Baylor University, Waco, Texas 76798-7264 (254) 710-3588, FAX: (254) 710-3870 e-mail: [email protected] Education B.S., Biology, University of Texas at Arlington, 1974 M.S., Wildlife & Fisheries Sciences, Texas A&M University, 1977 Ph.D., Zoology, University of Florida, 1982 Professional Experience Associate Dean of Graduate Studies and Research, Baylor Graduate School; Professor (tenured), Depts. of Biology and Geology, and in Institute of Biomedical Studies, Baylor University, June 2006-present. Courses taught: Mammalogy, Comparative Chordate Anatomy, Vertebrate Biology, Vertebrate Paleontology, Graduate Seminars in Biology, Graduate Proseminars in Interdisciplinary Scholarship. Associate Dean of Graduate Studies and Research, Baylor Graduate School; Professor (tenured) and Interim Graduate Program Director (Biology), Depts. of Biology and Geology, and in Institute of Biomedical Studies, Baylor University, September 2003-May 2006. Courses taught: Mammalogy, Comparative Chordate Anatomy, Vertebrate Natural History, Vertebrate Paleontology, Graduate Seminars in Biology, Graduate Proseminars in Interdisciplinary Teaching and Interdisciplinary Scholarship. Associate Dean of Graduate Studies and Research, Baylor Graduate School; Professor (tenured), Depts. of Biology and Geology, and in Institute of Biomedical Studies, Baylor University, September 2000-2003. Courses taught: Mammalogy (taught in Waco and at Chapala Ecology Station in Mexico), Comparative Chordate Anatomy, Vertebrate Natural History, Vertebrate Paleontology, Graduate Seminars in Biology, Graduate Proseminars in Interdisciplinary Teaching and Interdisciplinary Scholarship. Associate Dean of the Graduate School; Professor (tenured), Depts. of Biology and Geology, and in Institute of Biomedical Studies, Baylor University, June 1998-2000. -

Distribution of Baird's Pocket Gopher (Geomys Breviceps) in Arkansas; with Additional County Records Douglas A

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 50 Article 10 1996 Distribution of Baird's Pocket Gopher (Geomys breviceps) In Arkansas; with Additional County Records Douglas A. Elrod University of North Texas Gary A. Heidt University of Arkansas at Little Rock Mark R. Ingraham University of North Texas Earl G. Zimmerman University of North Texas Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Elrod, Douglas A.; Heidt, Gary A.; Ingraham, Mark R.; and Zimmerman, Earl G. (1996) "Distribution of Baird's Pocket Gopher (Geomys breviceps) In Arkansas; with Additional County Records," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 50 , Article 10. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol50/iss1/10 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 50 [1996], Art. 10 Distribution ofBaird's Pocket Gopher (Geomys breviceps) InArkansas With Additional County Records ? Douglas A.Elrod, Gary A.Heidt, Mark R. Ingraham and Earl G. -

Survey of the Current Distribution of the Southeastern Pocket Gopher ( Geomys Pinetis ) in Georgia

SURVEY OF THE CURRENT DISTRIBUTION OF THE SOUTHEASTERN POCKET GOPHER ( GEOMYS PINETIS ) IN GEORGIA Final Report to Georgia Department of Natural Resources Southern Wildlife Consults June 20, 2008 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The southeastern pocket gopher ( Geomys pinetis ) is listed as a high priority species for conservation in Georgia. Reports from the early 1980s suggested that the species’ distribution had been significantly reduced from its historic distribution in the state. Because the species was locally abundant in suitable habitats, but absent from large parts of historical range, habitat loss was considered a primary factor driving the distribution reduction. However, little information is available on current distribution and availability of suitable habitat. The overall goal of this project was to assess the current distribution and habitat associations of the southeastern pocket gopher in Georgia. Specific goals were to determine the current occupancy status of historic southeastern pocket gopher localities known from museum and publication records, to develop habitat models of pocket gopher presence or absence based habitat characteristics at occupied and random locations, and to apply the predictive model across the potential distribution in Georgia to identify additional areas where suitable habitat conditions exist. We obtained a compiled a list of 297 historic southeastern pocket gopher locations in Georgia from Paul Skelley at the Florida State Collection of Arthropods. We surveyed 272 (97% of useable locations) of the historical pocket gopher localities in 41 counties during a roadside survey from June-August 2006. We documented current pocket gopher activity at 65 (24%) of the historic locations in 18 counties. Using a kernel density estimator in the GIS, we identified 5 high pocket gopher density areas. -

Conrad Station Savanna Trail Is a 1.5 Mile Sided Towhee, Wild Turkey

Welcome to Conrad Station Savanna, The northern most part of the trail takes you TRAIL GUIDE owned and managed by the Indiana briefly out of the savanna, and into a tallgrass What to look for at Conrad Station Savanna Chapter of The Nature Conservancy. The prairie restoration. The depression along the The plant and animal species in Conrad Station north side of the trail is a small ephemeral 380 acres of Conrad Station contribute to Savanna are abundant and diverse. They are wetland, which holds water seasonally. A second uniquely adapted to the dry sandy soils and the conservation of Kankakee Sands, sign located further along the trail in the shade of occasional fires that keep savannas open and a large prairie-savanna complex in the savanna trees describes how The Nature sunny. Some of the commonly seen or heard northwest Indiana and northeast Illinois Conservancy manages the savanna at Conrad species are listed below. Let us know if you find Conrad Station Savanna that encompasses more than 30,000 acres Station Savanna as well as the unique plants and something of interest! at Kankakee Sands of land protected by the Conservancy and animals that live here. Birds: Orchard oriole, barred owl, blue grosbeak, its conservation partners. The southeastern part of the trail skirts the edge brown thrasher, vesper sparrow, field sparrow, lark sparrow, bobwhite quail, red-headed woodpecker, Hiking Conrad Station Savanna of a 75 acre prairie restoration completed in 1997. It was one of the first restorations planted rose-breasted grosbeak, scarlet tanager, rufous The Conrad Station Savanna Trail is a 1.5 mile sided towhee, wild turkey.