Abstracts for Other Oral Presentations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

Amphibian Biodiversity Recovery in a Large-Scale Ecosystem Restoration

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 1(2):101-108 Submitted: 10 May 2006; Accepted: 12 November 2006 AMPHIBIAN BIODIVERSITY RECOVERY IN A LARGE-SCALE ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION 1,2 1 1 3 ROBERT BRODMAN , MICHAEL PARRISH , HEIDI KRAUS AND SPENCER CORTWRIGHT 1Biology Department, Saint Joseph’s College, Rensselaer, Indiana, 47978, USA 2Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] 3Biology Department, Indiana University Northwest, Gary, Indiana, 46408 USA. Abstract.—Amphibians are important components of ecosystem function and processes; however, many populations have declined due to habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation. We studied the effect of wetlands ecosystem restoration on amphibian population recovery at Kankakee Sands in northwest Indiana, USA. We also tested predictions about colonization in relation to proximity to existing nature preserves and species characteristics. Prior to restoration activities (1998), the amphibian community at Kankakee Sands consisted of fourteen populations of seven species at seven breeding sites. By 2001, this community increased to 60 populations at 26 sites; however, species richness had not increased. By 2002 the community increased to 143 populations of eight species at 38 sites, and by 2003 there were 172 populations of ten species at 44 sites. Abundance index values increased 15-fold from 1998-2003. These increases best fit the exponential growth model. Although survival through metamorphosis was substantial during wetter than average years (2002 and 2003), during other years restored wetlands dried before larvae of most species transformed. Amphibian colonization was greatest near a nature preserve with the greatest amphibian diversity. The earliest colonists included fossorial species and those species whose habitat includes wet and mesic sand prairie. -

Lasalle Fish & Wildlife Area's Hardwood Forests, Fields And

LaSalle Fish & Wildlife Area’s hardwood forests, fields and marshes were once part of Grand Kankakee Marsh. 20 July/August 2017 EVERGLADES MINUS THE GATORS Telling the Grand Kankakee Marsh story helps restore it OutdoorIndiana.org 21 Quis eos voloreperion ped quam qui te eumenis am cone officidebis mos estis volut officitata imusdae vernatem quam, (Top, bottom) Eastern prickly pear (Opuntia humifusa), a cactus found at Kankakee Sands, is attractive, useful and edible; it also serves as food and cover for wildlife. Black-eyed Susan and tall grasses flourish at Kankakee Sands, which was once part of Grand Kankakee Marsh; the area packs a vast array of plants and wildlife in its more than 7,000 acres. 22 July/August 2017 By Nick Werner, OI staff To this day, many do not know of the marsh, let alone its Photography by Frank Oliver importance. Even some of the re-enactors who attend Aukiki are unaware, Hodson said. But a century later, the Kankakee’s story is rising from the ground like a ghost in a cemetery, searching for answers about fter the downpour ceased, four its demise. The spirit of the marsh has benefited from cold- women in bonnets and long case conservationists like Hodson. Archaeologists, farmers, dresses sang frontier-era folk hunters and even filmmakers have also played a role. Togeth- er, they are re-examining the region’s history, hoping to cor- songs in French. rect past mistakes. Their methods include creation of public Do they know? John Hodson wondered. A awareness, as well as land preservation, wetland restoration Probably not, he decided. -

Switchgrass – Reprinted from Friends of Hagerman NWR Weekly Blog, December 14, 2017 (Written by Linn Cates)

Switchgrass – Reprinted from Friends of Hagerman NWR Weekly Blog, December 14, 2017 (Written by Linn Cates) Switchgrass, Panicum virgatum, is a fast-growing, tall, warm weather perennial grass. It forms large, open, feathery looking, finely textured seed heads that transform it from a pleasing, but plainer look, (while the nearby spring and summer flowers demand the limelight) to an impressive, dressy fall showing. This continues, though somewhat subdued, right through the winter, until mid-spring when things warm up and a whole new chorus of green leaves emerge from the switchgrass crown to begin the show anew. Native to the North American prairie, switchgrass’s large range is east of the Rocky Mountains (south of latitude 55°N,) from Canada south through the United States and into Mexico. In Texas, it grows in all regions (below left in Comfort, TX) but is rare in the Trans-Pecos area of west Texas. In our part of Texas, North Central, you can see it at Clymer Meadow (above right), a large prairie remnant nearby in Hunt County, in native haying meadows near St. Jo in Montague County, at Austin College’s Sneed property in Grayson County, and at Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge among other places. But you could see it easily and up close by driving out to Hagerman NWR Visitor Center and taking a look in the Butterfly Garden right behind the parking area. You won’t miss it; one of the garden’s switchgrass specimens (below) has a plaque hanging in front of it, identifying it as “Switchgrass, Plant of the Month.” The repertoire of this performer, Panicum virgatum, is extensive. -

Prairie Restoration Technical Guides

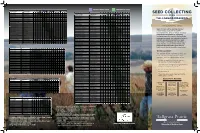

Optimal Collection Period Seed Ripening Period EARLY SEASON NATIVE FORBS May June July August September EARLY SEASON NATIVE FORBS May June July August SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 Caltha palustris Marsh marigold LATE SEASON NATIVE FORBS August September October November SEED COLLECTING Prairie smoke SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 FROM Antennaria neglecta Pussytoes Stachys palustris Woundwort Castilleja coccinea Indian paintbrush Vicia americana Vetch False dandelion Rudbeckia hirta Black-eyed Susan TALLGRASS PRAIRIES Saxifraga pensylvanica Swamp saxifrage Lobelia spicata Spiked lobelia Senecio aureus Golden ragwort Iris shrevei Sisyrinchium campestre Blue-eyed grass Hypoxis hirsuta Yellow star grass Rosa carolina Pasture rose Content by Greg Houseal Pedicularis canadensis Lousewort Oxypolis rigidior Cowbane PRAIRIE RESTORATION SERIES V Prairie violet Vernonia fasciculata Ironweed Cardamine bulbosa Spring cress Veronicastrum virginicum Culver's root Allium canadense Wild garlic Heliopsis helianthoides Seed of many native species are now Lithospermum canescens Hoary puccoon L Narrow-leaved loosestrife commercially1 available for prairie Phlox maculata Marsh phlox Lythrum alatum Winged loosestrife Phlox pilosa Prairie phlox reconstructions, large or small. Yet many Ceanothus americana New Jersey tea Anemone canadensis Canada anemone Eupatorium maculatum Spotted Joe Pye people have an interest in collecting Prunella vulgaris var. -

Kankakee Sands Ornate Box Turtle (Terrapene Ornata) Population & Ecosystem Assessment

I LLINOI S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. Kankakee Sands Ornate Box Turtle (Terrapene ornata) Population & Ecosystem Assessment Final Report Illinois Natural History Survey Center for Biodiversity Technical Report No. 2003 (35) Submitted in Fulfillment of Requirements of Wildlife Preservation Fund Grant: IDNR RC03L21W And The Nature Conservancy Grant: Nature Conserv 1131626100 4 December 2003 Christopher A. Phillips, Andrew R. Kuhns, and Timothy Hunkapiller Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 E.Peabody Drive, Champaign, IL 61820 Introduction The Kankakee Sands Macrosite is a complex of high-quality natural lands including wet/mesic sand prairie, oak barrens/savanna, and sedge meadows in northeast Illinois and northwest Indiana. A project is currently underway which targets over 7,500 acres of cropland and degraded grassland/savanna for restoration into a mosaic of native grasslands, savannas and wetlands which will ultimately restore connectivity to a landscape-scale system exceeding 40,000 acres. The Nature Conservancy, with assistance from professionals from IL DNR, IN DNR, INHS, and state universities, is in the process of completing a viability study for the Kankakee Sands Macrosite. One of the target species in the ornate box turtle (Terrapene ornata). It is easy to see why the ornate box turtle is considered a target species of sand prairies and savannas of the Kankakee Sands ecosystem. The turtle is associated with open habitats characterized by rolling topography with grasses and low shrubs as the dominant vegetation. Disturbance factors such as fire, grazing, and the presence of plains pocket gopher maintain the open structure of prairie and savannas which benefit the turtle. -

The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation

M DC, — _ CO ^. E CO iliSNrNVINOSHilWS' S3ldVyan~LIBRARlES*"SMITHS0N!AN~lNSTITUTl0N N' oCO z to Z (/>*Z COZ ^RIES SMITHSONIAN_INSTITUTlON NOIiniIiSNI_NVINOSHllWS S3ldVaan_L: iiiSNi'^NviNOSHiiNS S3iavyan libraries Smithsonian institution N( — > Z r- 2 r" Z 2to LI ^R I ES^'SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTlON'"NOIini!iSNI~NVINOSHilVMS' S3 I b VM 8 11 w </» z z z n g ^^ liiiSNi NviNOSHims S3iyvyan libraries Smithsonian institution N' 2><^ =: to =: t/J t/i </> Z _J Z -I ARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS SSIdVyan L — — </> — to >'. ± CO uiiSNi NViNosHiiws S3iyvaan libraries Smithsonian institution n CO <fi Z "ZL ~,f. 2 .V ^ oCO 0r Vo^^c>/ - -^^r- - 2 ^ > ^^^^— i ^ > CO z to * z to * z ARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNl NVINOSHllWS S3iaVdan L to 2 ^ '^ ^ z "^ O v.- - NiOmst^liS^> Q Z * -J Z I ID DAD I re CH^ITUCnMIAM IMOTtTIITinM / c. — t" — (/) \ Z fj. Nl NVINOSHIIINS S3 I M Vd I 8 H L B R AR I ES, SMITHSONlAN~INSTITUTION NOIlfl :S^SMITHS0NIAN_ INSTITUTION N0liniliSNI__NIVIN0SHillMs'^S3 I 8 VM 8 nf LI B R, ^Jl"!NVINOSHimS^S3iavyan"'LIBRARIES^SMITHS0NIAN~'lNSTITUTI0N^NOIin L '~^' ^ [I ^ d 2 OJ .^ . ° /<SS^ CD /<dSi^ 2 .^^^. ro /l^2l^!^ 2 /<^ > ^'^^ ^ ..... ^ - m x^^osvAVix ^' m S SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION — NOIlfliliSNrNVINOSHimS^SS iyvyan~LIBR/ S "^ ^ ^ c/> z 2 O _ Xto Iz JI_NVIN0SH1I1/MS^S3 I a Vd a n^LI B RAR I ES'^SMITHSONIAN JNSTITUTION "^NOlin Z -I 2 _j 2 _j S SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNI NVINOSHilWS S3iyVaan LI BR/ 2: r- — 2 r- z NVINOSHiltNS ^1 S3 I MVy I 8 n~L B R AR I Es'^SMITHSONIAN'iNSTITUTIOn'^ NOlin ^^^>^ CO z w • z i ^^ > ^ s smithsonian_institution NoiiniiiSNi to NviNosHiiws'^ss I dVH a n^Li br; <n / .* -5^ \^A DO « ^\t PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY ENTOMOLOGIST'S RECORD AND Journal of Variation Edited by P.A. -

Restoring the Prairie

Restoring the Prairie Grade: 3rd Season: Winter Time: 1 ½ hours Group Size: 1 class Ratio: 1:5 (adult: children) For the Teacher: Overview Students design an investigation about prairie restoration driven by their own questions. They participate directly in restoring the prairie by planting seeds in the prairie. (If possible, they may also be able to make observations of seedlings in the greenhouse and/or plant seeds there.) Lastly, they reflect upon their discoveries and answer their investigation questions. Subjects Covered Science MN Academic Helps support 17 standards. See section “2009 Minnesota Academic Standards Standards Supported in Science” and “2010 Minnesota Academic Standards in Language Arts.” Skills Used Investigating, following directions, listening, cooperating, asking and answering questions, observing, describing, measuring, sketching, reflecting, concluding, magnifying, collecting data, analyzing data, restoring habitat, thinking critically, writing, examining, discovering, teamwork, organizing Performance After completing this activity, students will be better able to… Objectives Identify two methods of prairie restoration (sowing in the field, sowing in the greenhouse and planting seedlings in the field) Name two kinds of prairie plants (grasses and forbs) Name at least one prairie plant species Plant prairie seeds in the field Explain why people restore prairie Enjoy making a difference improving the health of the prairie Vocabulary Investigate, prairie, restore, seedling, greenhouse, seeding/sowing, grass, forb, germinate, sowing For the PWLC Instructor: PWLC Theme The Prairie Pothole Region Primary EE Message The prairie pothole region is valuable and in need of restoration and protection. Sub-message People: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service works with others to preserve, manage, and restore prairie wetlands in the prairie pothole region. -

Prairie Reconstruction DRS CAROLYN GRYGIEL, JACK NORLAND and MARIO BIONDINI

© LINDA NORLAND Prairie reconstruction AND MARIO BIONDINI NORLAND JACK GRYGIEL, CAROLYN DRS Professor Emeritus and former Director of Natural Resources Management at North Dakota State University, Dr Carolyn Grygiel and her colleagues Drs Jack Norland and Mario Biondini are at the forefront of new methods for redressing the lost biodiversity of grasslands Firstly, as Director of Natural Resources to be pushing vegetation changes at the Are herbicides Management (NRM), how did you support landscape level. This new perspective led me or rototilling the faculty and student body in their to the concept of ‘patch dynamics’, which traditional management endeavours? would eventually focus on the impacts of options? Can they be applied small-scale disturbances as a model for sustainably? CG: While I was Director my main focus prairie reconstruction. was working with the undergraduate Herbicide application/drill seeding and and graduate students, inspiring them Is it feasible to ‘rewild’ these environments? rototilling/broadcast seeding are conventional to take the ‘long-term decision’ and ask Why must they be managed as prairie land? methods that take an agronomic, ie. farming, the ‘next big question.’ As is customary approach to restoring a natural system. While with interdisciplinary programmes, NRM Prairie reconstruction is feasible. Our both of these methods may prove initially was primarily dependent upon other research has shown that the installation effective, they are not generally sustainable departmental cohorts to provide our of small-scale disturbances and proper in that the forb component diminishes within graduate students with research projects seed mixtures can sustainably enhance a few years. We contend that the success and stipends. -

Woody-Invaded Prairie to Utility Prairie

Restoring Your Woody-Invaded Prairie to Utility Prairie The author of this Restoration Guide is Laura Phillips-Mao, University of Minnesota. Steve Chaplin, MN/ND/SD Chapter of The Nature Conservancy, administered the project and helped with production. Marybeth Block, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, provided review and editorial comments. Susan Galatowitsch, University of Minnesota, contributed to an earlier version of this guide. ©The Nature Conservancy January 1, 2017 Funding for the development of this restoration guide was provided by the Minnesota Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund as recommended by the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources (LCCMR) through grant LCCMR092C. The Trust Fund is a permanent fund constitutionally established by the citizens of Minnesota to assist in the protection, conservation, preservation, and enhancement of the state’s air, water, land, fish, wildlife, and other natural resources. Currently 40% of net Minnesota State Lottery proceeds are dedicated to building the Trust Fund and ensuring future benefits for Minnesota’s environment and natural resources. Additional funding for the update and redesign of the guide was provided by a Working Lands Initiative grant from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Cover photo taken at Sheepberry Fen Preserve by Alison Mickelson, Greater Good Photography. Restoring Your Woody- Why restore woody-invaded Invaded Prairie to prairies? Prairies that are not burned, grazed or mowed “Utility Prairie” are often invaded by woody trees and shrubs. In Minnesota, the prairie-forest border shifts In this guide, you will learn the basic steps to over time in response to changes in climate and restoring a degraded prairie invaded by woody fire frequency. -

Nine-Mile Prairie I

The Legacy of Nine-Mile Prairie I. Brief History II. Ecological Changes III. Environmental Changes IV. Changing Perspectives on Tallgrass Prairie Conservation John E. Weaver V. The Future of Nine-Mile Prairie (1884-1966) 1857: GLO Survey of 9MP – “The surface is of high rolling prairie”, no trees were noted. Bison and fire soon disappeared. 1885: Charles Bessey arrives at UNL 1898: Frederic Clements receives PhD UNL Early 1900’s: 9MP owned by the Flader family (west half), and the McManaman family (east half). Most of the area hayed annually. 1909: John E. Weaver receives BS UNL 1915: J.E. Weaver new Professor at UNL 1927-1928: First ecological descriptions for “800 acres of treeless, unbroken prairie” by T.L. Steiger, a PhD student of Weaver (published 1930) 1934: J.E. Weaver publishes “The Prairie” in State Historic Marker honoring Ecological Monographs (one of >100 publications) J.E. Weaver, post-storm 2017 1930’s: Drought and Dust Bowl 1949 1941: Professor Frank purchases eastern half of 9MP 1944: F.W. Albertson & J.E. Weaver publish “Nature & degree of recovery of grassland from the Great Drought 1933-1940” 1952: Weaver retires 1966: Weaver dies 1950: US Air Force takes over 9MP & surrounding area to support a Strategic Air Command Base (1952-1966). 1970’s: Lincoln Airport Authority acquires 9MP & Air Park. 9MP is rented by Ernie Rousek on behalf of Wachiska Audubon. 1981: Legislative Act (Bill 58) encourages LAA to protect 9MP (R.B. Crosby, E. Rousek, A.T. Harrison) 1984: NU Foundation purchases Nine-Mile Prairie (donation by Marguerite Hall) 2001: Michael Forsberg’s 9MP photo released as US postage stamp. -

Evaluation of Host Plant Resistance Against Sunflower Moth, <I

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations and Student Research in Entomology Entomology, Department of 8-2017 Evaluation of host plant resistance against sunflower moth, Homoeosoma electellum (Hulst), in cultivated sunflower in western Nebraska Dawn M. Sikora University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entomologydiss Part of the Entomology Commons Sikora, Dawn M., "Evaluation of host plant resistance against sunflower moth, Homoeosoma electellum (Hulst), in cultivated sunflower in western Nebraska" (2017). Dissertations and Student Research in Entomology. 50. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entomologydiss/50 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Student Research in Entomology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Evaluation of host plant resistance against sunflower moth, Homoeosoma electellum (Hulst), in cultivated sunflower in western Nebraska by Dawn Sikora A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Entomology Under the Supervision of Professors Jeff Bradshaw and Gary Brewer Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2017 Evaluation of host plant resistance against sunflower moth, Homoeosoma electellum (Hulst), in cultivated sunflower in western Nebraska Dawn Sikora, M.S. University of Nebraska, 2017 Advisors: Jeff Bradshaw and Gary Brewer Sunflower moth, Homoeosoma electellum, is a serious pest of oilseed and confection sunflowers. In this study, we determine efficacy of resistance against this pest. Thirty commercial hybrids, inbreds, and varieties of sunflowers were tested in replicated field and laboratory studies.