CHALLENGES at LAKE WINFIELD SCOTT RECREATION AREA By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIT HISTORIES Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of CIVIL WAR UNIT HISTORIES Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives Part 1. The Confederate States of America and Border States A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of CIVIL WAR UNIT HISTORIES Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives Part 1. Confederate States of America and Border States Editor: Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Civil War unit histories. The Confederate states of America and border states [microform]: regimental histories and personal narratives / project editors, Robert E. Lester, Gary Hoag. microfiches Accompanied by printed guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick. ISBN 1-55655-216-5 (microfiche) ISBN 1-55655-257-2 (guide) 1. United States--History~Civil War, 1861-1865--Regimental histories. 2. United States-History-Civil War, 1861-1865-- Personal narratives. I. Lester, Robert. II. Hoag, Gary. III. Hydrick, Blair. [E492] 973.7'42-dc20 92-17394 CIP Copyright© 1992 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-257-2. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction v Scope and Content Note xiii Arrangement of Material xvii List of Contributing Institutions xix Source Note xxi Editorial Note xxi Fiche Index Confederate States of America Army CSA-1 Navy CSA-9 Alabama AL-15 Arkansas AR-21 Florida FL-23 Georgia GA-25 Kentucky KY-33 Louisiana LA-39 Maryland MD-43 Mississippi MS-49 Missouri MO-55 North Carolina NC-61 South Carolina SC-67 Tennessee TN-75 Texas TX-81 Virginia VA-87 Author Index AI-107 Major Engagements Index ME-113 INTRODUCTION Nothing in the annals of America remotely compares with the Civil War. -

Georgia BMT Mile Features Services Elev. at Miles

Georgia 16.7 CAUTION: Turn sharply left here, leaving the ridgeline. Avoid old path that continues along the ridge. Descend steeply. BMT Features Services Elev. AT 17.0 Intersect old woods road and turn left, descending more gradually. Cross streambed (flowing in wet weather) and swing w Mile Miles right along streambed in cove. Leave cove, avoiding cabin straight ahead, and swing left. 17.4 -0.2 Springer Mountain—Springer has served as the A.T.’s southern terminus since 1958. Before that, Mt. Oglethorpe, to Descend steps to reach GA 60 (2028') at its intersection with FS 816. To left, GA 60 leads 16.6 mi. to the southwest, was the southern terminus. In 1993, GATC members and the Forest Service installed a new plaque Blue Ridge; to right it leads 30.8 mi. to Dahlonega. WARNING: The water from Little Skeenah Creek (across the marking the Trail’s southernmost blaze. The hiker register is located within the boulder on which the plaque is mounted. highway) is not for human consumption. There is a store 0.3 mi. to the right on GA 60 (south). Limited supplies, water, The origin of the mountain’s name is a bit foggy. The best guess is that it was named in honor of William G. Springer, a and telephone are available there. From GA 60 (2028'), proceed north 100 feet to cross Little Skeenah Creek on a bridge settler who, in 1833, was appointed by the Georgia governor to implement legislation to improve conditions for North constructed by the USFS and the BMTA in 1989. -

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located. -

America the Beautiful Part 1

America the Beautiful Part 1 Charlene Notgrass 1 America the Beautiful Part 1 by Charlene Notgrass ISBN 978-1-60999-141-8 Copyright © 2020 Notgrass Company. All rights reserved. All product names, brands, and other trademarks mentioned or pictured in this book are used for educational purposes only. No association with or endorsement by the owners of the trademarks is intended. Each trademark remains the property of its respective owner. Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations are taken from the New American Standard Bible®, Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by the Lockman Foundation. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Cover Images: Jordan Pond, Maine, background by Dave Ashworth / Shutterstock.com; Deer’s Hair by George Catlin / Smithsonian American Art Museum; Young Girl and Dog by Percy Moran / Smithsonian American Art Museum; William Lee from George Washington and William Lee by John Trumbull / Metropolitan Museum of Art. Back Cover Author Photo: Professional Portraits by Kevin Wimpy The image on the preceding page is of Denali in Denali National Park. No part of this material may be reproduced without permission from the publisher. You may not photocopy this book. If you need additional copies for children in your family or for students in your group or classroom, contact Notgrass History to order them. Printed in the United States of America. Notgrass History 975 Roaring River Rd. Gainesboro, TN 38562 1-800-211-8793 notgrass.com Thunder Rocks, Allegany State Park, New York Dear Student When God created the land we call America, He sculpted and painted a masterpiece. -

Safe Haven in Rocky Fork Hiawassee

JOURNEYS THE MAGAZINE OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY January – February 2013 INSIDE: Safe Haven in Rocky Fork ❙ Hiawassee, Georgia ❙ Creative Collaboration ❘ JOURNEYS From thE EDitor THE MAGAZINE OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY Volume 9, Number 1 PRACTICAL MAGIC. WHEN I HEAR THE woRDs “MAGIC,” aNd “ENCHANTMENT” January – February 2013 to describe the Appalachian Trail, I think of another kind of magic that happens behind the scenes. Consider how closely the Trail skirts a densely-populated portion of the country; then consider any A.T. trailhead from Georgia to Maine a doorway to a peaceful, wooded path, strewn Mission with pristine waterways, grassy balds, and high ridge lines, and it does indeed sound like illusion The Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s mission is to preserve and manage the Appalachian Trail — ensuring — but the magic is real. that its vast natural beauty and priceless cultural heritage can be shared and enjoyed today, tomorrow, A recent letter sent to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) headquarters especially and for centuries to come. punctuates this message. “In a way, it was like going back in time — leaving the modern and finding a much less complicated way of life alive in our country,” wrote ATC member Mary Holmes after completing her hike of the Trail. She continued with these Board of Directors A.T. Journeys poignant words: “The Trail is a miracle — first that it exists intact and J. Robert (Bob) Almand ❘ Chair Wendy K. Probst ❘ Managing Editor that it weaves through the most developed part of the country. It William L. (Bill) Plouffe ❘ Vice Chair Traci Anfuso-Young ❘ Graphic Designer should be an example in years to come of the value of conservation On the Cover: Kara Ball ❘ Secretary and inspire ever-greater conservation efforts.” The Trail is a model for “As winter scenes go, very few top the Arthur Foley ❘ Treasurer Contributors success, due to the serious and pragmatic work of the ATC staff beauty of fresh snow and ice clinging Lenny Bernstein Laurie Potteiger ❘ Information Services Manager members, A.T. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Introduction to the Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan

SOUTHERN BLUE RIDGE ECOREGIONAL CONSERVATION PLAN Summary and Implementation Document March 2000 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY and the SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN FOREST COALITION Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan Summary and Implementation Document Citation: The Nature Conservancy and Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition. 2000. Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan: Summary and Implementation Document. The Nature Conservancy: Durham, North Carolina. This document was produced in partnership by the following three conservation organizations: The Nature Conservancy is a nonprofit conservation organization with the mission to preserve plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. The Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition is a nonprofit organization that works to preserve, protect, and pass on the irreplaceable heritage of the region’s National Forests and mountain landscapes. The Association for Biodiversity Information is an organization dedicated to providing information for protecting the diversity of life on Earth. ABI is an independent nonprofit organization created in collaboration with the Network of Natural Heritage Programs and Conservation Data Centers and The Nature Conservancy, and is a leading source of reliable information on species and ecosystems for use in conservation and land use planning. Photocredits: Robert D. Sutter, The Nature Conservancy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This first iteration of an ecoregional plan for the Southern Blue Ridge is a compendium of hypotheses on how to conserve species nearest extinction, rare and common natural communities and the rich and diverse biodiversity in the ecoregion. The plan identifies a portfolio of sites that is a vision for conservation action, enabling practitioners to set priorities among sites and develop site-specific and multi-site conservation strategies. -

Milebymile.Com Personal Road Trip Guide Georgia State Highway #180 "Suches to Georgia State Highway #17/75"

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide Georgia State Highway #180 "Suches to Georgia State Highway #17/75" Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 Welcome to Georgia Community of Suches, Georgia. Suches is an unincorporated area in Union County in the Georgia mountains, Suches is truly a paradise for outdoor activities. If you like to hike, bird watch, fish, hunt, camp or just sit under a tree and enjoy the clean mountain air. This is the place!. Activities: Hiking; Appalachian Trail ~ Benton MacKaye Trail ~ Duncan Ridge Trail ~ Three Forks Trail Millshoals Trail ~ Cooper Creek Trail ~ Yellow Mountain Trail Blood Mountain Archeological Area. Fishing: Toccoa River ~ Cooper Creek ~ Lake Winfield Scott ~ Deep Hole ~ Dockery Lake. Other scenic areas include: Sosebee Cove ~ Woody Gap ~ Chestatee Overlook ~ Sea Creek Falls Cooper Creek Wildlife Management Area ~ Chattahoochee Forest National Fish Hatchery. 0.0 Junction GA Hwy 60 Western portion of GA Hwy. 180 aka GA 180W; also known as Wolfpen Gap Rd, starts in Suches, Georgia at Junction with GA Hwy #60. Suches is called 'A Valley Above the Clouds. Suches is located in the Chattahoochee National Forest Recreation Area. Ten wildernesses, 1,367 miles of trout streams, and 430 miles of trails enrich the Chattahoochee National Forest. The famous 2,135-mile Appalachian Trail begins here and hardy hikers don't see the end until they reach Maine! Drive along the Ridge and Valley Scenic Byway, which tours the Armuchee Ridges of the Appalachian Mountains. 1.1 Church Mt. Lebanon Baptist Church 1.7 Church Harmony Church of God 2.1 Farm Miller Gap Farm 3.6 Bottled Water Plant Appalachian Springs, producer of North Georgia Mountain Spring Water 3.7 Church Zion Baptist Church 4.3 Lake Winfield Scott, First entrance to Lake Winfield Scott Recreation Area - clear 18 acre Georgia Lake, high in the mountains with camping, swimming, fishing, boating and hiking. -

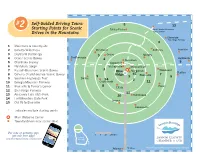

Starting Points for Scenic Drives in the Mountains

# Self-Guided Driving Tours: 5 2 12 Starting Points for Scenic Tellico Plains Great Smoky Mountains Drives in the Mountains National Park Cherokee Blue Ridge Parkway 6 1 Mountains & Countryside 2 Cohutta Wilderness Cleveland Andrews Franklin 3 Daytrip to Dahlonega 9 Ocoee Murphy 4 Ocoee Scenic Byway Chattanooga Highlands 4 Ducktown 5 Cherohala Skyway TENNESSEE Copperhill NORTH CAROLINA 9 6 Nantahala Gorge GEORGIA McCaysville Mineral Bluff GEORGIA 7 Russell-Brasstown Scenic Byway 2 Morganton Hiawassee Blue Clayton 8 Cohutta-Chattahoochee Scenic Byway Ridge 15 7 9 1 Blairsville 9 9 Southern Highroads Trail* Dalton 14 3 10 Georgia Mountain Parkway Chatsworth 11 11 Blairsville to Turner’s Corner 8 Ellijay Helen 12 Blue Ridge Parkway 13 13 Amicalola Falls State Park 10 Dahlonega 14 Fort Mountain State Park Jasper 15 Old 76 to Blairsville S u r ro Dawsonville u n * indicates multiple starting points d ed B y S cen Main Welcome Center ery Town/landmark near scenic drive For lots of activity info get our free App! 0 5 10 15 Miles GEORGIA www.blueridgemountains.com/App.html MAP AREA N Atlanta 75 Miles ©2017 TreasureMaps.com All rights reserved 7 Russell-Brasstown Scenic Byway, From Blairsville take Springer Mountain, the southern end of the Appalachian Trail. # Self-Guided Driving Tours: Starting Hwy. 129/19 south to Hwy. 180 (turn left) then Hwy. 348 is Directions: From Blue Ridge, take Hwy 515 south to Hwy 52 2 Points for Scenic Mountain Drives just a mile away and is marked as the Richard Russell Scenic outside of Ellijay. Follow Hwy 52 to the left fork toward Highway. -

Big Bald Bird Banding Family Hiking Shared History

JOURNEYS THE MAGAZINE OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY July — August 2012 INSIDE: Big Bald Bird Banding ❙ Family Hiking ❙ Shared History: A.T. Presidential Visits ❘ JOURNEYS FROM THE EDITOR THE MAGAZINE OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY Volume 8, Number 4 APPALacHIAN MIGRATION. A PROTECTED PATH AS UNIQUE AS THE A.T. OFFERS ALL OF ITS July — August 2012 visitors and natural inhabitants the freedom to progress, in both a literal and figurative sense. In this way the Appalachian Trail is a migratory path, providing hikers the autonomy to wander through lush fields, along roll- ing grassy balds, and up and over rugged but fiercely beautiful mountains from which they are given a glimpse Mission of the vantage point of high-flying birds. And by way of the Trail and its corridor, the birds too are given freedom The Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s mission is to preserve and manage the Appalachian Trail — ensuring to travel — high above and safely through the fields, forests, and Appalachian Mountains of the eastern U.S. that its vast natural beauty and priceless cultural heritage can be shared and enjoyed today, tomorrow, Along the North Carolina and Tennessee mountains of the Trail, the Big Bald Banding Station, operated by and for centuries to come. volunteers from Southern Appalachian Raptor Research, monitors the passage of thousands of winged A.T. inhabitants. “[It] is one of very few banding stations in the U.S. that monitors and bands songbirds, raptors, and On the Cover: Nevena “Gangsta” owls. An average of 2,000 passerines are captured, banded, and safely released during each autumn migration Martin carefully crosses a stream in Board of Directors A.T. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G3862 SOUTHERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3862 FEATURES, ETC. .C55 Clayton Aquifer .C6 Coasts .E8 Eutaw Aquifer .G8 Gulf Intracoastal Waterway .L6 Louisville and Nashville Railroad 525 G3867 SOUTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3867 FEATURES, ETC. .C5 Chattahoochee River .C8 Cumberland Gap National Historical Park .C85 Cumberland Mountains .F55 Floridan Aquifer .G8 Gulf Islands National Seashore .H5 Hiwassee River .J4 Jefferson National Forest .L5 Little Tennessee River .O8 Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail 526 G3872 SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3872 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .B6 Blue Ridge Mountains .C5 Chattooga River .C52 Chattooga River [wild & scenic river] .C6 Coasts .E4 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Area .N4 New River .S3 Sandhills 527 G3882 VIRGINIA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G3882 .A3 Accotink, Lake .A43 Alexanders Island .A44 Alexandria Canal .A46 Amelia Wildlife Management Area .A5 Anna, Lake .A62 Appomattox River .A64 Arlington Boulevard .A66 Arlington Estate .A68 Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial .A7 Arlington National Cemetery .A8 Ash-Lawn Highland .A85 Assawoman Island .A89 Asylum Creek .B3 Back Bay [VA & NC] .B33 Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge .B35 Baker Island .B37 Barbours Creek Wilderness .B38 Barboursville Basin [geologic basin] .B39 Barcroft, Lake .B395 Battery Cove .B4 Beach Creek .B43 Bear Creek Lake State Park .B44 Beech Forest .B454 Belle Isle [Lancaster County] .B455 Belle Isle [Richmond] .B458 Berkeley Island .B46 Berkeley Plantation .B53 Big Bethel Reservoir .B542 Big Island [Amherst County] .B543 Big Island [Bedford County] .B544 Big Island [Fluvanna County] .B545 Big Island [Gloucester County] .B547 Big Island [New Kent County] .B548 Big Island [Virginia Beach] .B55 Blackwater River .B56 Bluestone River [VA & WV] .B57 Bolling Island .B6 Booker T.