Indian Cinema's Original Rebel Hero – Dev Anand Dev Anand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

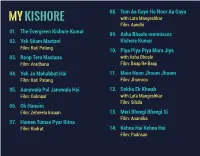

Tribute to Kishore Kumar

Articles by Prince Rama Varma Tribute to Kishore Kumar As a child, I used to listen to a lot of Hindi film songs. As a middle aged man, I still do. The difference however, is that when I was a child I had no idea which song was sung by Mukesh, which song by Rafi, by Kishore and so on unlike these days when I can listen to a Kishore song I have never heard before and roughly pinpoint the year when he may have sung it as well as the actor who may have appeared on screen. On 13th October 1987, I heard that Kishore Kumar had passed away. In the evening there was a tribute to him on TV which was when I discovered that 85% of my favourite songs were sung by him. Like thousands of casual music lovers in our country, I used to be under the delusion that Kishore sang mostly funny songs, while Rafi sang romantic numbers, Mukesh,sad songs…and Manna Dey, classical songs. During the past twenty years, I have journeyed a lot, both in music as well as in life. And many of my childhood heroes have diminished in stature over the years. But a few…..a precious few….have grown……. steadily….and continue to grow, each time I am exposed to their brilliance. M.D.Ramanathan, Martina Navratilova, Bruce Lee, Swami Vivekananda, Kunchan Nambiar, to name a few…..and Kishore Kumar. I have had the privilege of studying classical music for more than two and a half decades from some truly phenomenal Gurus and I go around giving lecture demonstrations about how important it is for a singer to know an instrument and vice versa. -

Nationalmerit-2020.Pdf

Rehabilitation Council of India ‐ National Board of Examination in Rehabilitation (NBER) National Merit list of candidates in Alphabatic Order for admission to Diploma Level Course for the Academic Session 2020‐21 06‐Nov‐20 S.No Name Father Name Application No. Course Institute Institute Name Category % in Class Remark Code Code 12th 1 A REENA PATRA A BHIMASEN PATRA 200928134554 0549 AP034 Priyadarsini Service Organization, OBC 56.16 2 AABHA MAYANK PANDEY RAMESH KUMAR PANDEY 200922534999 0547 UP067 Yuva Viklang Evam Dristibadhitarth Kalyan Sewa General 75.4 Sansthan, 3 AABID KHAN HAKAM DEEN 200930321648 0547 HR015 MR DAV College of Education, OBC 74.6 4 AADIL KHAN INTZAR KHAN 200929292350 0527 UP038 CBSM, Rae Bareli Speech & Hearing Institute, General 57.8 5 AADITYA TRIPATHI SOM PRAKASH TRIPATHI 200921120721 0549 UP130 Suveera Institute for Rehabilitation and General 71 Disabilities 6 AAINA BANO SUMIN MOHAMMAD 200926010618 0550 RJ002 L.K. C. Shri Jagdamba Andh Vidyalaya Samiti OBC 93 ** 7 AAKANKSHA DEVI LAKHAN LAL 200927081668 0550 UP044 Rehabilitation Society of the Visually Impaired, OBC 75 8 AAKANKSHA MEENA RANBEER SINGH 200928250444 0547 UP119 Swaraj College of Education ST 74.6 9 AAKANKSHA SINGH NARENDRA BAHADUR SING 201020313742 0547 UP159 Prema Institute for Special Education, General 73.2 10 AAKANSHA GAUTAM TARACHAND GAUTAM 200925253674 0549 RJ058 Ganga Vision Teacher Training Institute General 93.2 ** 11 AAKANSHA SHARMA MAHENDRA KUMAR SHARM 200919333672 0549 CH002 Government Rehabilitation Institute for General 63.60% Intellectual -

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

Volume-13-Skipper-1568-Songs.Pdf

HINDI 1568 Song No. Song Name Singer Album Song In 14131 Aa Aa Bhi Ja Lata Mangeshkar Tesri Kasam Volume-6 14039 Aa Dance Karen Thora Romance AshaKare Bhonsle Mohammed Rafi Khandan Volume-5 14208 Aa Ha Haa Naino Ke Kishore Kumar Hamaare Tumhare Volume-3 14040 Aa Hosh Mein Sun Suresh Wadkar Vidhaata Volume-9 14041 Aa Ja Meri Jaan Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Jawab Volume-3 14042 Aa Ja Re Aa Ja Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Ankh Micholi Volume-3 13615 Aa Mere Humjoli Aa Lata Mangeshkar Mohammed RafJeene Ki Raah Volume-6 13616 Aa Meri Jaan Lata Mangeshkar Chandni Volume-6 12605 Aa Mohabbat Ki Basti BasayengeKishore Kumar Lata MangeshkarFareb Volume-3 13617 Aadmi Zindagi Mohd Aziz Vishwatma Volume-9 14209 Aage Se Dekho Peechhe Se Kishore Kumar Amit Kumar Ghazab Volume-3 14344 Aah Ko Chahiye Ghulam Ali Rooh E Ghazal Ghulam AliVolume-12 14132 Aah Ko Chajiye Jagjit Singh Mirza Ghalib Volume-9 13618 Aai Baharon Ki Sham Mohammed Rafi Wapas Volume-4 14133 Aai Karke Singaar Lata Mangeshkar Do Anjaane Volume-6 13619 Aaina Hai Mera Chehra Lata Mangeshkar Asha Bhonsle SuAaina Volume-6 13620 Aaina Mujhse Meri Talat Aziz Suraj Sanim Daddy Volume-9 14506 Aaiye Barishon Ka Mausam Pankaj Udhas Chandi Jaisa Rang Hai TeraVolume-12 14043 Aaiye Huzoor Aaiye Na Asha Bhonsle Karmayogi Volume-5 14345 Aaj Ek Ajnabi Se Ashok Khosla Mulaqat Ashok Khosla Volume-12 14346 Aaj Hum Bichade Hai Jagjit Singh Love Is Blind Volume-12 12404 Aaj Is Darja Pila Do Ki Mohammed Rafi Vaasana Volume-4 14436 Aaj Kal Shauqe Deedar Hai Asha Bhosle Mohammed Rafi Leader Volume-5 14044 Aaj -

My God, That's My Tune'

The composer recently made it on the New York hit parade with a song titled In every city. In an interview R. D. Burman talks about his craft. Left: R. D. Burman with Latin American composer Jose Flores. Below: The 'Pantera' team, among others R.D. Burman (centre), Jose Flores and (far right) Pete Gavankar. HENEVER an Indian achieves a Wmilestone abroad, he instantly gets more recognition in his own coun- try. Perhaps it's the colonial hangover that still makes us believe that they are always right over there. In this case however, the distinction is not going to make any difference as the person gaining it is already a household name here. Rahul Dev Burman, who has given music for 225 Hindi films, has made it to the New York hit parade with a song titled In every city. He is all set to launch the album—'Pantera'—in India. Two people have been responsible for getting him there—his father Sachin Dev Burman who was the only member of the family willing to let him enter films, and Pete Gavankar, a friend of thirty years who goaded him into seek- ing new pastures and has financed the album. Intrigued, we decided to find out just how the international album had come about and while we were at it, also gauge just how much R.D. had already packed into his life of 45 years. It turned out to be much more than we had thought as we had to have several sittings before we were through. But R.D. -

California State University, Northridge The

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE THE PREPARATION OF THE ROLE OF TOM MOODY IN CLIFFORD ODETS' GOLDEN BOY An essay submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Theatre by Robert T. Hollander June, 1981 The Essay of Robert T. Hollander is approved: Prof. c(§!g Nieuwenhuysel Dr. Georg~ Gunkle, Committee Chairman California State University, Northridge ii ABSTRACT THE PREPARATION OF THE ROLE OF TOM MOODY IN CLIFFORD ODETS' GOLDEN BOY by Robert T. Hollander Master of Arts in Theatre Golden Boy was first produced by the Group Theatre in New York in 1937. Directed by Harold Clurman, this 1937 production included in its cast names that were to become notable in the American theatre: Luther Adler, Frances Farmer, Lee J. Cobb, Jules (John) Garfield, Morris Carnovsky, Elia Kazan, Howard Da Silva and Karl Malden. Golden Boy quickly became the most successful production 1 in Group Theatre history and was followed in 1939 by the movie of the same name, starring William Holden and Barbara Stanwyck. Since then, there have been countless revivals, including a musical adaptation in 1964 which starred Sammy Davis Jr. Golden Boy certainly merits consideration as one of the classics of modern American drama. 1Harold Clurman, The Fervent Years: The Story of the Group Theatre and the Thirties. (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. A Harvest Book, 1975), p. 211. 1 2 The decision to prepare the character of Torn Moody as a thesis project under the direction of Dr. George Gunkle was made during the spring semester of 1980 at which time I was performing a major role in The Knight of the Burning Pestle, a seventeenth century farce written by Beaumont and Fletcher. -

Ajeeb Aadmi—An Introduction Ismat Chughtai, Sa'adat Hasan Manto

Ajeeb Aadmi—An Introduction I , Sa‘adat Hasan Manto, Krishan Chandar, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Kaifi Azmi, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Ali Sardar Jafri, Majaz, Meeraji, and Khawaja Ahmed Abbas. These are some of the names that come to mind when we think of the Progressive Writers’ Movement and modern Urdu literature. But how many people know that every one of these writers was also involved with the Bombay film indus- try and was closely associated with film directors, actors, singers and pro- ducers? Ismat Chughtai’s husband Shahid Latif was a director and he and Ismat Chughtai worked together in his lifetime. After Shahid’s death Ismat Chughtai continued the work alone. In all, she wrote scripts for twelve films, the most notable among them ◊iddµ, Buzdil, Sån® kµ ≤µ∞y≥, and Garm Hav≥. She also acted in Shyam Benegal’s Jun∑n. Khawaja Ahmed Abbas made a name for himself as director and producer for his own films and also by writing scripts for some of Raj Kapoor’s best- known films. Manto, Krishan Chandar and Bedi also wrote scripts for the Bombay films, while all of the above-mentioned poets provided lyrics for some of the most alluring and enduring film songs ever to come out of India. In remembering Kaifi Azmi, Ranjit Hoskote says that the felicities of Urdu poetry and prose entered the consciousness of a vast, national audience through the medium of the popular Hindi cinema; for which masters of Urdu prose, such as Sadat [sic] Hasan Manto, wrote scripts, while many of the Progressives, Azmi included, provided lyrics. -

Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber

Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber TAILORING EXPECTATIONS How film costumes become the audience’s clothes ‘Bollywood’ film costume has inspired clothing trends for many years. Female consumers have managed their relation to film costume through negotiations with their tailor as to how film outfits can be modified. These efforts have coincided with, and reinforced, a semiotic of female film costume where eroticized Indian clothing, and most forms of western clothing set the vamp apart from the heroine. Since the late 1980s, consumer capitalism in India has flourished, as have films that combine the display of material excess with conservative moral values. New film costume designers, well connected to the fashion industry, dress heroines in lavish Indian outfits and western clothes; what had previously symbolized the excessive and immoral expression of modernity has become an acceptable marker of global cosmopolitanism. Material scarcity made earlier excessive costume display difficult to achieve. The altered meaning of women’s costume in film corresponds with the availability of ready-to-wear clothing, and the desire and ability of costume designers to intervene in fashion retailing. Most recently, as the volume and diversity of commoditised clothing increases, designers find that sartorial choices ‘‘on the street’’ can inspire them, as they in turn continue to shape consumer choice. Introduction Film’s ability to stimulate consumption (responding to, and further stimulating certain kinds of commodity production) has been amply explored in the case of Hollywood (Eckert, 1990; Stacey, 1994). That the pleasures associated with film going have influenced consumption in India is also true; the impact of film on various fashion trends is recognized by scholars (Dwyer and Patel, 2002, pp. -

Result Jmu Kath-Udh-Distt.Pdf

GRAND S.NO. ROLL NO NAME OF CANDIDATE PARENTAGE RESULT TOTAL 1 FW-I/18176 Monika Khajuria Sh. Chaman Lal 173 FAIL 2 FW-I/18177 Neha Kumari Sh. Dharam Chand 229 PASS 3 FW-I/18178 Tanvi Sharma Sh. Vijander Sharam 198 PASS 4 FW-I/18179 Roshni Chanda Sh. Jeet Raj Chanda 237 PASS 5 FW-I/18180 Pooja Devi Sh. Rattan Lal 201 PASS 6 FW-I/18181 Manjeet Kour Sh. Attar Singh 204 PASS 7 FW-I/18182 Daljeet Kour Sh. Mohinder Singh 192 PASS 8 FW-I/18183 Anjali Bhagta Sh. Tirath Ram 243 PASS 9 FW-I/18184 Sunnia Bhatti Sh. David 222 PASS 10 FW-I/18185 Ashwani Devi Sh. Tula Ram 200 PASS 11 FW-I/18186 Prabhjot Kaur Sh. Inderjeet Singh 194 PASS 12 FW-I/18187 Neha Kumari Sh. Sudesh Jamwal 180 FAIL 13 FW-I/18188 Manju Bala Sh. Tirth Ram 195 PASS 14 FW-I/18189 Arti Devi Sh. Sham Lal 198 PASS 15 FW-I/18190 Rekha Devi Sh. Mohinder Lal 213 PASS 1 FW-II/18196 Bindu Kumari Sh. Kartar Chand 187 PASS 2 FW-II/18197 Komal Sh. Rajesh Kumar 197 PASS 3 FW-II/18198 Neha Choudhary Sh. Gurdeep Singh 144 FAIL 4 FW-II/18199 Seema Sharma Sh. Suresh Kumar Sharma 213 PASS 5 FW-II/18200 Waheeda Hamid Tantry Ab. Hamid Tantry 198 PASS 6 FW-II/18201 Tsering Dolkar Sh. Tsering Gyalson 22 ABSENT 7 FW-II/18202 Sangay Dolma Sh. Skarma Stanzin 246 PASS 8 FW-II/18203 Sangeeta Devi Sh. -

The Lessons of Mumbai

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation occasional paper series. RAND occasional papers may include an informed perspective on a timely policy issue, a discussion of new research methodologies, essays, a paper presented at a conference, a conference summary, or a summary of work in progress. All RAND occasional papers undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

SD Burman Booklet

SD BURMAN - 200 SONGS 11. Phoolon Ke Rang Se Artiste: Kishore Kumar 01. Kora Kagaz Tha Film: Prem Pujari Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar & Lyricist: Neeraj Kishore Kumar 12. Aaj Phir Jeene Ki Film: Aradhana Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Lyricist: Anand Bakshi Film: Guide 02. Khoya Khoya Chand Lyricist: Shailendra Artiste: Mohammed Rafi 13. Tere Mere Sapne Ab Film: Kala Bazar Artiste: Mohammed Rafi Lyricist: Shailendra Film: Guide 03. Teri Bindiya Re Lyricist: Shailendra Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar & 14. Hum Aap Ki Ankhon Mein Mohammed Rafi Artistes: Geeta Dutt & Mohammed Rafi Film: Abhimaan Film: Pyaasa Lyricist: Majrooh Sultanpuri Lyricist: Sahir Ludhianvi 04. Mana Janab Ne Pukara 15. Ab To Hai Tumse Har Artiste: Kishore Kumar Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Film: Paying Guest Film: Abhimaan Lyricist: Majrooh Sultanpuri Lyricist: Majrooh Sultanpuri 05. Mere Sapnon Ki Rani 16. Din Dhal Jaye Haye Artiste: Kishore Kumar Artiste: Mohammed Rafi Film: Aradhana Film: Guide Lyricist: Anand Bakshi Lyricist: Shailendra 06. Ek Ladki Bheegi Bhagi Si 17. Aasman Ke Neeche Artiste: Kishore Kumar Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar & Film: Chalti Ka Nam Gaadi Kishore Kumar Lyricist: Majrooh Sultanpuri Film: Jewel Thief 07. Tere Mere Milan Ki Lyricist: Majrooh Sultanpuri Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar & 18. Aaye Tum Yaad Mujhe Kishore Kumar Artiste: Kishore Kumar Film: Abhimaan Film: Mili Lyricist: Majrooh Sultanpuri Lyricist: Yogesh 08. Gaata Rahe Mera Dil 19. Yeh Dil Na Hota Bechara Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar & Artiste: Kishore Kumar Kishore Kumar Film: Jewel Thief Film: Guide Lyricist: Majrooh Sultanpuri Lyricist: Shailendra 20. Hum Bekhudi Mein Tum Ko 09. Dil Ka Bhanwar Artiste: Mohammed Rafi Artiste: Mohammed Rafi Film: Kala Pani Film: Tere Ghar Ke Samne Lyricist: Majrooh Sultanpuri Lyricist: Hasrat Jaipuri 21. -

Kishore Booklet Copy

08. Tum Aa Gaye Ho Noor Aa Gaya with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Aandhi 01. The Evergreen Kishore Kumar 09. Asha Bhosle reminisces 02. Yeh Sham Mastani Kishore Kumar Film: Kati Patang 10. Piya Piya Piya Mora Jiya 03. Roop Tera Mastana with Asha Bhosle Film: Aradhana Film: Baap Re Baap 04. Yeh Jo Mohabbat Hai 11. Main Hoon Jhoom Jhoom Film: Kati Patang Film: Jhumroo 05. Aanewala Pal Janewala Hai 12. Dekha Ek Khwab Film: Golmaal with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Silsila 06. Oh Hansini Film: Zehreela Insaan 13. Meri Bheegi Bheegi Si Film: Anamika 07. Hamen Tumse Pyar Kitna Film: Kudrat 14. Kehna Hai Kehna Hai Film: Padosan 2 3 15. Raat Kali Ek Khwab Mein 23. Mere Sapnon Ki Rani Film: Buddha Mil Gaya Film: Aradhana 16. Aate Jate Khoobsurat Awara 24. Dil Hai Mera Dil Film: Anurodh Film: Paraya Dhan 17. Khwab Ho Tum Ya Koi 25. Mere Dil Mein Aaj Kya Hai Film: Teen Devian Film: Daag 18. Aasman Ke Neeche 26. Ghum Hai Kisi Ke Pyar Mein with Lata Mangeshkar with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Jewel Thief Film: Raampur Ka Lakshman 19. Mere Mehboob Qayamat Hogi 27. Aap Ki Ankhon Mein Kuch Film: Mr. X In Bombay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Ghar 20. Teri Duniya Se Hoke Film: Pavitra Papi 28. Sama Hai Suhana Suhana Film: Ghar Ghar Ki Kahani 21. Kuchh To Log Kahenge Film: Amar Prem 29. O Mere Dil Ke Chain Film: Mere Jeevan Saathi 22. Rajesh Khanna talks about Kishore Kumar 4 5 30. Musafir Hoon Yaron 38. Gaata Rahe Mera Dil Film: Parichay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Guide 31.