Software As a Medical Device a Comparison of the EU’S Approach with the US’S Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patient-Monitoring Systems

17 Patient-Monitoring Systems REED M. GARDNER AND M. MICHAEL SHABOT After reading this chapter,1 you should know the answers to these questions: ● What is patient monitoring, and why is it done? ● What are the primary applications of computerized patient-monitoring systems in the intensive-care unit? ● How do computer-based patient monitors aid health professionals in collecting, analyzing, and displaying data? ● What are the advantages of using microprocessors in bedside monitors? ● What are the important issues for collecting high-quality data either automatically or manually in the intensive-care unit? ● Why is integration of data from many sources in the hospital necessary if a computer is to assist in critical-care-management decisions? 17.1 What Is Patient Monitoring? Continuous measurement of patient parameters such as heart rate and rhythm, respira- tory rate, blood pressure, blood-oxygen saturation, and many other parameters have become a common feature of the care of critically ill patients. When accurate and imme- diate decision-making is crucial for effective patient care, electronic monitors frequently are used to collect and display physiological data. Increasingly, such data are collected using non-invasive sensors from less seriously ill patients in a hospital’s medical-surgical units, labor and delivery suites, nursing homes, or patients’ own homes to detect unex- pected life-threatening conditions or to record routine but required data efficiently. We usually think of a patient monitor as something that watches for—and warns against—serious or life-threatening events in patients, critically ill or otherwise. Patient monitoring can be rigorously defined as “repeated or continuous observations or meas- urements of the patient, his or her physiological function, and the function of life sup- port equipment, for the purpose of guiding management decisions, including when to make therapeutic interventions, and assessment of those interventions” (Hudson, 1985, p. -

Dec 3 1 2013

X 133704. DEC 3 1 2013 510(K) Summary for M1 Capnography Mask 1. Submission Sponsor Monitor Mask, Inc. 551543 dAvenue NE Seattle WA, 98105 USA Phone: 877.226.1776 Contact: JW Beard MD, MBA, Founder and CEO 2. Submission Correspondent Emergo, Group, Inc. 816 Congress Avenue, Suite 1400 Austin, TX 78701 office Phone: (512) 327.9997 Fax: (512) 327.9998 Contact: Stuart RGoldman, Senior Consultant, RA/QA Email: oroiect.manapement~emerpogroup.com 3. Date Prepared September 20, 2013 4. Device Identification Trade/Proprietary Name: M1 Capnography Mask Common/Usual Name: oxygen/capnography mask Classification Name: analyzer, gas, carbon-dioxide, gaseous-phase Classification Regulation: §868.1400 Product Code: CCK (primary); BYG (secondary) Device Class: Class 11 Classification Panel: Anesthesiology 5. Legally Marketed Predicate Device CapnoxygenO Mask (K(971229) manufactured by Medlsys (Southmedic) 6. Device Description The M1 Capnography Mask is connected to a gas source for delivering low flow oxygen through flexible tubing to the patient, and at the same time provides a means to attach a capnograph for monitoring exhaled carbon dioxide during nose and mouth breathing. The capnograph gas sample tube attaches to a standard female Luer connector on either the left or right side of the M1 Capnography Mask. The M1 Capnography Mask will initially be made available in only one size, adult large (Model #001). Page 5-1 7. Indication for Use Statement The M1 Capnography Mask is a single-use device intended for delivering supplemental oxygen and monitoring exhaled carbon dioxide in non-intubated spontaneously breathing patients. Standard oxygen tubing and two female Luer ports for gas sample line attachment are included. -

Serious Adverse Event Reporting Under Directives 90/385/Eec and 93/42/Eec

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DG Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs Consumer, Environmental and Health Technologies Health technology and Cosmetics MEDDEV 2.7/3 revision 3 May 2015 GUIDELINES ON MEDICAL DEVICES CLINICAL INVESTIGATIONS: SERIOUS ADVERSE EVENT REPORTING UNDER DIRECTIVES 90/385/EEC AND 93/42/EEC. Note The present Guidelines are part of a set of Guidelines relating to questions of application of EC-Directives on medical Devices. They are legally not binding. The Guidelines have been carefully drafted through a process of intensive consultation of the various interested parties (competent authorities, Commission services, industries, other interested parties) during which intermediate drafts where circulated and comments were taken up in the document. Therefore, this document reflects positions taken by representatives of interest parties in the medical devices sector. These guidelines incorporate changes introduced by Directive 2007/47/EC amending Council Directive 90/385/EEC and Council Directive 93/42/EEC. 1 MEDICAL DEVICES DIRECTIVES CLINICAL INVESTIGATION GUIDELINES FOR ADVERSE EVENT REPORTING UNDER DIRECTIVES 90/385/EEC AND 93/42/EEC Index 1. INTRODUCTION 2. SCOPE 3. DEFINITIONS 4. REPORTABLE EVENTS 5. REPORT BY WHOM 6. REPORT TO WHOM 7. REPORTING TIMELINES 8. CAUSALITY ASSESSMENT 9. REPORTING FORM Appendix – Summary Reporting Form 2 1. INTRODUCTION This guidance defines Serious Adverse Event (SAE) reporting modalities and includes a summary tabulation reporting format. Individual reporting should be performed in accordance with national requirements. The objective of this guidance is to contribute to the notification of SAEs to all concerned National Competent Authorities (NCAs ) 1 in the context of clinical investigations in line with the requirements of Annex 7 of Directive 90/385/EEC and Annex X of Directive 93/42/EEC, as amended by Directive 2007/47/EC. -

Medical Device Software Regulation Software Qualification And

AHWP/WG1/R001:2014 REFERENCE DOCUMENT (DRAFT for Public Comments) Title: White Paper on Medical Device Software Regulation – Software Qualification and Classification Author: Work Group 1, Pre-Market Submission and CSDT Date 22 May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by the Asian Harmonization Working Party Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 2 2. Definitions ................................................................................................................................ 2 3. Types of Software that are Regulated as Medical Devices ........................................... 4 4. Forms of Medical Device Software .................................................................................... 4 5. SaMD Medical Device Software Classification Globally .............................................. 6 5.1. International Medical Device Regulatory Forum (IMDRF) .................................... 6 5.1.1. IMDRF qualification criteria .......................................................................................... 6 5.2. Australia TGA ..................................................................................................................... 7 5.2.2. Risk classification of software in TGA ...................................................................... 7 5.3. China .................................................................................................................................... -

Ministry of Medical Services Pharmacy and Poisons Board Kenya

MINISTRY OF MEDICAL SERVICES PHARMACY AND POISONS BOARD KENYA GUIDELINES ON SUBMISSION OF DOCUMENTATION FOR REGISTRATION OF MEDICAL DEVICES FIRST EDITION September, 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PREFACE Medical Device Regulation in Kenya will be supervised and directed by Kenya Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB). Classification, requirements and evaluation of Medical Devices will be mainly simulation of rules and regulations recognized by the international regulatory benchmarks, which are mainly: a. The Pharmacy and Poisons Act Chapter 244 of 2002 b. Global Harmonization Task Force (GHTF) for Medical Device c. EU Medical Device Directives 93/42/EEC, EU In Vitro Diagnostic Device Directive Ministry of Medical Services Page 2 of 2 Pharmacy and Poisons Board Kenya (IVDD) 98/79/EC and EU Active Implantable Medical Device Directive (AIMDD) 90/385/EEC. d. US FDA (United States Food & Drug Administration) e. Australia TGA (Therapeutics Goods Act) The regulation of medical devices in Kenya is aimed at maintaining balance between ensuring product safety, quality and effectiveness and providing the public with timely access to medical devices and preventing the entrance of unsafe or ineffective devices into the market. SCOPE These guidelines shall apply to medical devices and their accessories. For the purposes of these guidelines, accessories shall be treated as medical devices in their own right. Where a device is intended to administer a medicinal product, that device shall be governed by this guideline, without prejudice to the corresponding regulations for registration of medicinal products for human use set by the PPB. If, however, such a device is placed on the market in such a way that the device and the medicinal product form a single integral product which is intended exclusively for use in the given combination and which is not reusable, that single product shall be governed by corresponding regulations for registration of medicinal products for human use set by the PPB. -

Data Protection on Pharmacovigilance and Medical Device Safety

DATA PROTECTION ON PHARMACOVIGILANCE AND MEDICAL DEVICE SAFETY General Galena Pharma Oy, founded in 1996, is a pharmaceutical company specialising in contract manufacturing and packaging. A significant part of the service includes product development, registration & marketing authorization and post-market surveillance. The wide range of our products comprises human and veterinary medicinal products, medical devices in Classes IIa and IIb, cosmetics, food supplements, animal care products and nutritional supplements. The products we manufacture are sold mainly in pharmacies. Galena Pharma has a legal obligation to monitor the adverse events and the effects of their products in the countries where they are getting sold and carry out a continuous risk-benefit assessment. It is called pharmacovigilance and medical device safety operation. With the help of this system and quality assurance management, Galena Pharma can manage adverse events and protect public health. Thanks to this, the safety of Galena Pharma's products is guaranteed. It is the responsibility of the competent authority to inspect and evaluate the pharmacovigilance and medical device safety activities of the company and validate it. Pharmacovigilance and medical device safety obligate Galena Pharma to process the information of the patient and/or the notifier of the adverse reaction, based on which a person can be directly or indirectly identified. These are personal data whose processing is mandatory for Galena Pharma in order to comply with its pharmacovigilance and medical device safety obligations and report any adverse reactions or events that come to their notice to the competent authorities in a relevant and appropriate manner. This privacy statement describes how personal data gets processed for pharmacovigilance and medical device safety purposes under applicable data protection laws and the obligations set out in the EU Data Protection Regulation (EU 2016/679). -

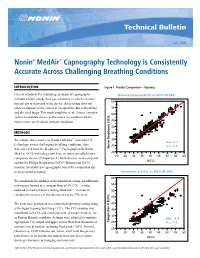

Nonin® Medair™ Capnography Technology Is Consistently Accurate Across Challenging Breathing Conditions

Technical Bulletin July 2009 Nonin® MedAir™ Capnography Technology is Consistently Accurate Across Challenging Breathing Conditions INTRODUCTION Figure 1: Product Comparison – Accuracy Current standards for evaluating accuracy of capnographs NoninNonin RespSense RespSense EtCOEtCO2 vs NICONICO (N-364)(N=364) includes simple, steady flow gas validation in which a known 60 percent gas is delivered to the device. Such testing does not allow evaluation of the effects of complexities due to breathing 55 and diseased lungs. This study sought to create a more complex 2 50 system to evaluate device performance in conditions which better represented realistic patient conditions. 45 40 METHODS 35 Resp EtCO2 To evaluate the accuracy of Nonin’s MedAir™ end-tidal CO 30 2 Bias: 0.2 technology across challenging breathing conditions, data 25 Arms: 2.6 was collected from the RespSense™ Capnograph with Nonin Nonin RespSense EtCO 20 MedAir EtCO2 technology and from an internationally known 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 competitor device (Competitor A). Both devices were compared ® NICO against the Philips Respironics NICO Mainstream EtCO2 monitor, a mainstream capnograph chosen for comparison due Root Mean Square Error 2.563916 Mean of Response 0.178683 to its accepted accuracy. CompetitorNellcor EtCO A EtCO2 vs2 NICOvs NICO (N=364) (N-364) 60 To compliment the findings of the simulation testing, an additional 55 test was performed at a constant flow of 5% CO2—a value required in medical device testing standards1—in order to 50 validate the accuracy of the devices at a static CO2 level. 2 45 The tests were performed in a controlled laboratory setting using 40 a Michigan Training Test Lung (TTL). -

21 Ncac 46 .2513 Drug, Supplies and Medical Device

21 NCAC 46 .2513 DRUG, SUPPLIES AND MEDICAL DEVICE REPOSITORY PROGRAM (a) This Rule establishes the Drug, Supplies and Medical Device Repository Program as specified in G.S. 90-85.44. (b) Definitions. Any term defined in G.S. 90-85.44(a) shall have the same definition under this Rule. (c) Requirements For a Pharmacy to Participate in Accepting and Dispensing Donated Drugs, Supplies and Medical Devices. (1) Any pharmacy or free clinic holding a valid, current North Carolina pharmacy permit may accept and dispense donated drugs, supplies and medical devices in accordance with the requirements of this Rule and G.S. 90-85.44. (2) A dispensing physician registered with the Board in compliance with G.S. 90-85.21(b) and providing services to patients of a free clinic that does not hold a pharmacy permit may accept and dispense donated drugs, supplies and medical devices in accordance with the requirements of this Rule and G.S. 90-85.44. (3) A participating pharmacy or dispensing physician shall notify the Board in writing of such participation at the time participation begins and annually on its permit or registration renewal application. (4) A participating pharmacy or dispensing physician that ceases participation in the program shall notify the Board in writing within 30 days of doing so and shall submit a written report detailing the final disposition of all donated drugs, supplies and medical devices held by the participating pharmacy or dispensing physician. (d) Drugs, Supplies and Medical Devices Eligible for Donation. (1) A participating pharmacy or dispensing physician may accept donation of a drug, supply or medical device meeting the criteria specified in G.S. -

Testing and Labeling Medical Devices for Safety in the Magnetic Resonance (MR) Environment Final Guidance

Welcome to today’s FDA/CDRH Webinar Thank you for your patience while additional time is provided for participants to join the call. Please connect to the audio portion of the webinar now: U.S. Dial: 1-888-455-1392 International Dial: 1 - 773- 799 - 3847 Conference Number: PWXW2186446 Audience Passcode: 5723246 Testing and Labeling Medical Devices for Safety in the Magnetic Resonance (MR) Environment Final Guidance Sunder Rajan Division of Biomedical Physics Office of Science and Engineering Laboratories Center for Devices and Radiological Health June 24, 2021 2 Agenda and Objectives • Overview of interactions of medical devices with Magnetic Resonance (MR) environment • Background on the existing approaches for the testing of devices for the safe use in the MR environment • Description of the final guidance on Testing and Labeling Medical Devices for Safety in the Magnetic Resonance (MR) Environment • Questions about the final guidance 3 Overview: Interactions of Medical Devices with MR Environment STATIC FIELD MAGNET SYSTEMS CONTROL RADIOFREQUENCY GRADIENT COILS (RF) ELECTRONICS RF RESONATOR TRANSMITTER RECEIVER RF RESONATOR GRADIENT CURRENT GRADIENT COILS AMPLIFIERS STATIC FIELD MAGNET 1. Static magnetic field + spatial gradient à attractive and torqueing forces: projectile effect, device displacement 2. Time varying magnetic field gradients à induced currents in metal surface, current loop: device malfunction, tissue stimulation, device heating 3. Pulsed radiofrequency (RF) energy à Intense electromagnetic (EM) fields, antenna effect: -

Telemedicine and Mobile Health Innovations Amid Increasing Regulatory Oversight

COMMENTARY Telemedicine and mobile health innovations amid increasing regulatory oversight By Sharon Klein, Esq., and Jee-Young Kim, Esq. Pepper Hamilton LLP The growing mobile health market is rapidly UNDERSTANDING TELEMEDICINE transforming health care delivery. More than AND MOBILE HEALTH 80 percent of physicians use mobile technology Telemedicine involves direct patient care to provide patient care, and more than and is a subcategory of telehealth, a broader 25 percent of commercially insured patients use concept that includes telecommunications mobile applications to manage their health.1 technologies, or mobile medical applications, Technological advancements, the expansion to remotely support health care, health- of access to health care under the Patient related education, public health and health Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. administration.3 Generally, telemedicine L. No. 111-148, the emphasis on cost- involves: effective quality care and the proliferation • Geographic separation between two or of mobile medical applications have pushed more participants or entities engaged in telemedicine to the new frontier of health care delivery. health care. Over the past 50 years, the scope of • The use of telecommunications tech- telemedicine practices has expanded to nology to gather, store and disseminate meet demands for immediate care in both health-related information. remote and metropolitan regions. Mobile • The use of interactive technologies to health, a form of telemedicine using wireless assess, diagnose and treat medical devices and cell phone technologies, conditions. has also evolved. By the end of this year, Mobile health is a medium through which experts expect 2 billion smartphones, telemedicine is practiced. It allows for tablets and other portable devices globally, increased provider and patient mobility, each of which can potentially provide as well as greater delivery of clinical care individuals access to health care information via consumer-grade hardware, such as The WebMD app is shown here. -

Medical Device Interactions with Magnetic Resonance Imaging Systems

This guidance was written prior to the February 27, 1997 implementation of FDA's Good Guidance Practices, GGP's. It does not create or confer rights for or on any person and does not operate to bind FDA or the public. An alternative approach may be used if such approach satisfies the requirements of the applicable statute, regulations, or both. This guidance will be updated in the next revision to include the standard elements of GGP's A Primer on Medical Device Interactions with Magnetic Resonance Imaging Systems DRAFT DOCUMENT This document is being distributed for comment purposes only. CDRH Magnetic Resonance Working Group Draft released for comment on: February 7, 1997 The Federal Register notice reopening the comment period for this document was published May 22, 1997, and extends the comment period to August 20, 1997. Comments and suggestions regarding this draft document should be submitted to Marlene Skopec, Office of Science and Technology, HFZ-133, 12721 Twinbrook Pkwy, Rockville, MD 20852. Comments and suggestions received after August 20, 1997, may not be acted upon by the Agency until the document is next revised or updated. For questions regarding this draft document, contact Marlene Skopec at (301) 443-3840. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health Table of Contents 1.0 Scope/Purpose 1 2.0 Definitions 2 3.0 Introduction and Overview of Medical Device Concerns 4 Table 1: MR Environment Medical Device Concerns 5 Table 2: Effect of Medical Device on -

Design Verification – the Case for Verification, Not Validation

Design Verification – The Case for Verification, Not Validation Overview: The FDA requires medical device companies to verify that all the design outputs meet the design inputs. The FDA also requires that the final medical device must be validated to the user needs. When there are so many more design inputs and outputs than specific user needs, why do companies spend so little time verifying the device and so much time and money on validation? And what is the role of risk management in determining the amount of testing required? This presentation will demonstrate that if developers conduct more complete verifications of design outputs and risk mitigations, validations can be completed in a shorter time, more reliably, and more successfully. Introduction: In our experience working with medical device manufacturers to improve their Quality Management Systems and to gain regulatory clearance of new devices, we have found that Design Verification is an often underutilized tool for ensuring success during the latter stages of device development efforts. In many cases, limited verification efforts represent a lost opportunity to significantly reduce the scope of validation efforts – and thereby reduce time to market and development costs. This paper explores the use and misuse of Design Verification and how device manufactures can get the most out of their verification efforts. But first, some background . Background: Medical device manufacturers have been working to align their design and development systems with the FDA’s design control regulations (21 CFR 820.30) since their release in 1996. The regulations are structured to ensure that device manufacturers maintain control over their designs throughout the development process and that the marketed device is safe and effective for its intended use.