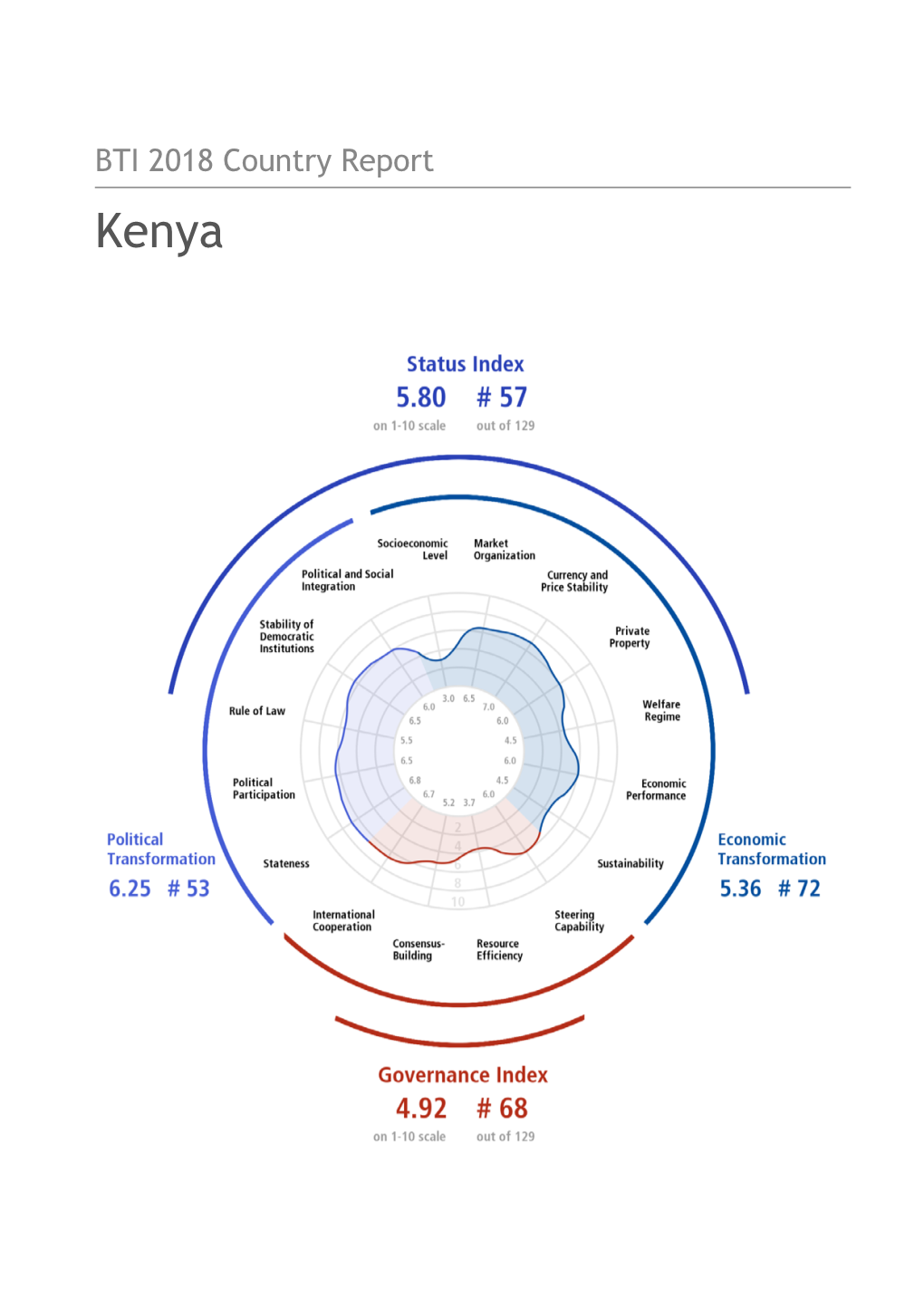

Kenya Country Report BTI 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elections in Kenya: 2017 Rerun Presidential Election Frequently Asked Questions

Elections in Kenya 2017 Rerun Presidential Elections Frequently Asked Questions Africa International Foundation for Electoral Systems 2011 Crystal Drive | Floor 10 | Arlington, VA 22202 | www.IFES.org October 25, 2017 Frequently Asked Questions Acronym list .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Why is Kenya holding a second presidential election? ................................................................................. 2 What challenges does the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission face in organizing the rerun election? .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Will voters use any form of electronic voting? ............................................................................................. 5 What technology will be used during the October presidential election? ................................................... 5 What are areas of concern regarding potential electoral violence? ............................................................ 5 Who is eligible to run as a candidate in this election? ................................................................................. 7 What type of electoral system will be used to elect the president? ............................................................ 8 Will members of the diaspora be able to vote in this election? .................................................................. -

Bank Code Finder

No Institution City Heading Branch Name Swift Code 1 AFRICAN BANKING CORPORATION LTD NAIROBI ABCLKENAXXX 2 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD MOMBASA (MOMBASA BRANCH) AFRIKENX002 3 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD NAIROBI AFRIKENXXXX 4 BANK OF BARODA (KENYA) LTD NAIROBI BARBKENAXXX 5 BANK OF INDIA NAIROBI BKIDKENAXXX 6 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. ELDORET (ELDORET BRANCH) BARCKENXELD 7 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (DIGO ROAD MOMBASA) BARCKENXMDR 8 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (NKRUMAH ROAD BRANCH) BARCKENXMNR 9 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BACK OFFICE PROCESSING CENTRE, BANK HOUSE) BARCKENXOCB 10 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BARCLAYTRUST) BARCKENXBIS 11 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (CARD CENTRE NAIROBI) BARCKENXNCC 12 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (DEALERS DEPARTMENT H/O) BARCKENXDLR 13 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (NAIROBI DISTRIBUTION CENTRE) BARCKENXNDC 14 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL SERVICES) BARCKENXPIS 15 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PLAZA BUSINESS CENTRE) BARCKENXNPB 16 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (TRADE PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXTPC 17 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (VOUCHER PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXVPC 18 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI BARCKENXXXX 19 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (BANKING DIVISION) CBKEKENXBKG 20 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (CURRENCY DIVISION) CBKEKENXCNY 21 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (NATIONAL DEBT DIVISION) CBKEKENXNDO 22 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI CBKEKENXXXX 23 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI (STRUCTURED PAYMENTS) SBICKENXSSP 24 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI SBICKENXXXX 25 CHARTERHOUSE BANK LIMITED NAIROBI CHBLKENXXXX 26 CHASE BANK (KENYA) LIMITED NAIROBI CKENKENAXXX 27 CITIBANK N.A. NAIROBI NAIROBI (TRADE SERVICES DEPARTMENT) CITIKENATRD 28 CITIBANK N.A. -

Njuguna Ndung'u: Shariah-Compliant Banking and Finance in Kenya

Njuguna Ndung’u: Shariah-compliant banking and finance in Kenya Remarks by Prof Njuguna Ndung’u, Governor of the Central Bank of Kenya, at the launch of the First Community Bank’s Mutual Fund, Nairobi, 6 March 2012. * * * Ms. Stella Kilonzo, Chief Executive, Capital Markets Authority; Mr. Steve Mainda, Chairman, Insurance Regulatory Authority; Mr. Hassan Varvani, Chairman, First Community Bank Ltd; Mr. Abdullatif Essajee, Managing Director, First Community Bank Ltd; Mr. Nathif Adam, Director, First Community Bank Capital; All the Excellencies here present; Board Members of First Community Bank Ltd here present; Distinguished Guests; Ladies and Gentlemen: I am delighted to be with you this evening at the launch of First Community Bank’s Shariah- compliant mutual fund and to celebrate the success of Islamic Finance. Allow me at the outset to compliment the Board and Management of First Community Bank Ltd for growing the bank from a start-up operation in April 2008, to an institution now boasting of deposits amounting to Ksh.7.3 billion and assets of Ksh.8.4 billion as at 31st January 2012. Indeed, First Community Bank Ltd pioneered the establishment of Shariah-compliant banking in Kenya and I am happy to note that the bank has continued to keep up the momentum by introducing a range of innovative Shariah-compliant products. These products will go a long way in deepening Kenya’s financial sector. We can now boast of having a full-fledged Shariah-compliant financial infrastructure, thanks to the effort of Nathif Adam. Ladies and Gentlemen: Kenya has not been left behind in the world-wide phenomenal growth of Shariah-compliant finance and banking and huge gains have been made since its inception. -

NATIONAL SUPER ALLIANCE Chairman, Article 86 of The

NATIONAL SUPER ALLIANCE 10th August 2017 Mr. Wafula Chebukati Chairperson IEBC National Tallying Center Bomas of Kenya Nairobi Chairman, RE: PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION RESULT Article 86 of the Constitution requires as follows “At every election, the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission shall ensure that— (a) whatever voting method is used, the system is simple, accurate, verifiable, secure, accountable and transparent; (b) the votes cast are counted, tabulated and the results announced promptly by the presiding officer at each polling station; (c) the results from the polling stations are openly and accurately collated and promptly announced by the returning officer; and (d) appropriate structures and mechanisms to eliminate electoral malpractice are put in place, including the safekeeping of election materials.” We have information of the actual presidential election results contained in the IEBC database. NATIONAL SUPER ALLIANCE The data, which confirm the authentic and legitimate result of the presidential election, shows that the two leading candidates obtained the following votes: • Raila Amolo Odinga 8,041726 votes • Uhuru Kenyatta 7,755,428 Votes Screenshots of the results as displayed on your website and monitors at Bomas show the following results: • Uhuru Kenyatta 8,056,885 • Raila Amolo Odinga 6,659,493 Evidently, the accurate and lawful results in the presidential election is the transmission received from the polling stations and contained in the IEBC servers. We have annexed the following: • The actual and complete data contained in IEBC servers (dbo.PRESIDENTIAL_REAL_TIME); and • The screenshots obtained from the IEBC website. We therefore demand as follows: 1. That you stop forthwith the display of unverified and unauthenticated results. -

KDIC Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 - 2018 ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2018 Prepared in accordance with the Accrual Basis of Accounting Method under the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) CONTENTS Key Entity Information..........................................................................................................1 Directors and statutory information......................................................................................3 Statement from the Board of Directors.................................................................................11 Report of the Chief Executive Officer...................................................................................12 Corporate Governance statement........................................................................................15 Management Discussion and Analysis..................................................................................19 Corporate Social Responsibility...........................................................................................27 Report of the Directors.......................................................................................................29 Statement of Directors' Responsibilities................................................................................30 Independent Auditors' Report.............................................................................................31 Financial Statements: Statement of Profit or Loss and other Comprehensive Income...................................35 -

Provider Id Provider Name 00203Ea2-8Be5-434B-82Aa

Provider Id Provider Name 00203ea2-8be5-434b-82aa-a968cdccc71c Centric Bank 002b95bb-472e-4316-8e26-eefcb26af6dd Northland Area Federal Credit Union (MI) 004139df-1233-4846-8007-655902d283f3 Forte Bank - Business 005119b7-d11b-4149-8875-d810ce1119f7 Town & Country Bank - UT 00678017-3dd3-48d9-96dd-49f2a75df3ad Fulton Financial CashLink East 00686d39-a1ca-4a18-bb42-88c5e9af95e4 Iowa Nebraska State Bank(Now BankFirst (NE)) 006ccff2-c2b5-461b-93fe-a345efdbf885 Lanco FCU 0080f77d-a78c-41e8-b9c4-8d49cdec1f6a Boat U.S. MBNA CC 0093d12e-d5de-456c-a1d8-f10770405be9 1st Bank of Sea Isle City - Business Banking 009515cf-b944-4002-88fe-66aaeace40ed Citizens Bank & Trust (OK) 00c5e357-6071-4a90-ac44-4eb96183e162 First Utah Bank 00cdd410-208a-47dd-bc29-a9627cadf68f Sentry Bank 00f83a8c-5959-4604-a7ec-bd00583ad99f Farmers State Bank (IN) 0122685c-3eaa-4a8a-ab9c-616ba5f6b24e Home Federal Savings and Loan Association of Collinsville 014c1f5b-0bd5-45a7-b648-86f4c869b01b Grasslands Federal Credit Union 0169eb89-0c80-445d-a13a-8933b512d4cf ZZ OGRAF SLLEW 016afc49-673c-4f09-b3d5-f24a7a1eea24 Atlantic Capital Bank (GA) Sun West Bank, Las Vegas NV - Business Banking (Now City National 016d3ab7-b5d3-482a-8767-822372a1e380 Bank, CA - Business Online) 0176b604-c675-4412-a792-8d1578bdf48c First Port City Bank (GA) 017aeb6a-9d51-4c9b-8ead-b8d3a5a95f53 First National Bank and Trust (FL) 019e9909-f57d-4e3c-b494-751939a0c234 First National Bank Minnesota - Business Banking 01a03d99-694c-4888-a79a-5bcf3ae3e650 First Iowa State Bank Albia 01ab7eee-ec30-49b9-8476-4804f34abb31 -

NASA Manifesto

A STRONG NATION NATIONAL SUPER ALLIANCE COALITION MANIFESTO 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 3 Nation Building 4 State Building 9 DRAFTTransforming Governance 13 Realizing Social and Economic Rights 18 Creating Jobs, Eradicating Poverty 22 Regional and International Cooperation 37 1 NATIONAL SUPER ALLIANCE MANIFESTO NATIONAL SUPER ALLIANCE MANIFESTO FOREWORD NASA Coalition exists to pursue five objectives namely, to promote national unity, to uphold, guard and respect the dignity of all individuals and communities, to return country to the path of constitutional and democratic development; end the culture of impunity; and to restore sanity in the management of the economy and public affairs of our Nation. These objectives are enunciated in the Coalition Agreement between the five founder political parties namely Amani National Congress (ANC), Chama Cha Mashinani (CCM), Forum for the Restoration of Democracy Kenya (FORD-Kenya), Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) and the Wiper Democratic Movement Kenya (WDM-Kenya) The Coalition is governed by progressive values and principles of democracy, constitutionalism and the rule of law; equality and equity, including affirmative action; human rights, dignity and freedom; inclusive governance, equitable, sustainable development and social justice; transparent, accountable and accessible leadership; empowered citizens who actively participate in governance and policy processes; free, vigorous media and vibrant civil society, freedom of information; zero tolerance to corruption; and free, fair and credible -

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 Bank: 01 Kenya Commercial Bank Limited (Clearing centre: 01) Branch code Branch name 091 Eastleigh 092 KCB CPC 094 Head Office 095 Wote 096 Head Office Finance 100 Moi Avenue Nairobi 101 Kipande House 102 Treasury Sq Mombasa 103 Nakuru 104 Kicc 105 Kisumu 106 Kericho 107 Tom Mboya 108 Thika 109 Eldoret 110 Kakamega 111 Kilindini Mombasa 112 Nyeri 113 Industrial Area Nairobi 114 River Road 115 Muranga 116 Embu 117 Kangema 119 Kiambu 120 Karatina 121 Siaya 122 Nyahururu 123 Meru 124 Mumias 125 Nanyuki 127 Moyale 129 Kikuyu 130 Tala 131 Kajiado 133 KCB Custody services 134 Matuu 135 Kitui 136 Mvita 137 Jogoo Rd Nairobi 139 Card Centre Page 1 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 140 Marsabit 141 Sarit Centre 142 Loitokitok 143 Nandi Hills 144 Lodwar 145 Un Gigiri 146 Hola 147 Ruiru 148 Mwingi 149 Kitale 150 Mandera 151 Kapenguria 152 Kabarnet 153 Wajir 154 Maralal 155 Limuru 157 Ukunda 158 Iten 159 Gilgil 161 Ongata Rongai 162 Kitengela 163 Eldama Ravine 164 Kibwezi 166 Kapsabet 167 University Way 168 KCB Eldoret West 169 Garissa 173 Lamu 174 Kilifi 175 Milimani 176 Nyamira 177 Mukuruweini 180 Village Market 181 Bomet 183 Mbale 184 Narok 185 Othaya 186 Voi 188 Webuye 189 Sotik 190 Naivasha 191 Kisii 192 Migori 193 Githunguri Page 2 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 194 Machakos 195 Kerugoya 196 Chuka 197 Bungoma 198 Wundanyi 199 Malindi 201 Capital Hill 202 Karen 203 Lokichogio 204 Gateway Msa Road 205 Buruburu 206 Chogoria 207 Kangare 208 Kianyaga 209 Nkubu 210 -

Bank Supervision Annual Report 2019 1 Table of Contents

CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA BANK SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS VISION STATEMENT VII THE BANK’S MISSION VII MISSION OF BANK SUPERVISION DEPARTMENT VII THE BANK’S CORE VALUES VII GOVERNOR’S MESSAGE IX FOREWORD BY DIRECTOR, BANK SUPERVISION X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY XII CHAPTER ONE STRUCTURE OF THE BANKING SECTOR 1.1 The Banking Sector 2 1.2 Ownership and Asset Base of Commercial Banks 4 1.3 Distribution of Commercial Banks Branches 5 1.4 Commercial Banks Market Share Analysis 5 1.5 Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) 7 1.6 Asset Base of Microfinance Banks 7 1.7 Microfinance Banks Market Share Analysis 9 1.8 Distribution of Foreign Exchange Bureaus 11 CHAPTER TWO DEVELOPMENTS IN THE BANKING SECTOR 2.1 Introduction 13 2.2 Banking Sector Charter 13 2.3 Demonetization 13 2.4 Legal and Regulatory Framework 13 2.5 Consolidations, Mergers and Acquisitions, New Entrants 13 2.6 Medium, Small and Micro-Enterprises (MSME) Support 14 2.7 Developments in Information and Communication Technology 14 2.8 Mobile Phone Financial Services 22 2.9 New Products 23 2.10 Operations of Representative Offices of Authorized Foreign Financial Institutions 23 2.11 Surveys 2019 24 2.12 Innovative MSME Products by Banks 27 2.13 Employment Trend in the Banking Sector 27 2.14 Future Outlook 28 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA 2 BANK SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER THREE MACROECONOMIC CONDITIONS AND BANKING SECTOR PERFORMANCE 3.1 Global Economic Conditions 30 3.2 Regional Economy 31 3.3 Domestic Economy 31 3.4 Inflation 33 3.5 Exchange Rates 33 3.6 Interest -

Submission of Political Party Nomination Rules

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SUBJECT: SUBMISSION OF POLITICAL PARTY NOMINATION RULES NAIROBI, KENYA: Wednesday, March 8th, 2017 – The Commission is in the process of reviewing the nomination rules submitted by 67 registered political parties to ensure compliance with the prescribed guidelines and respond to the democratic principles of governance as espoused by Article 91 of the Constitution. One provisionally registered political party and one Coalition also submitted their nomination rules. The Commission published a public notice requiring Political Parties to submit Nomination Rules by 2nd March, 2017. Political Parties are further reminded to submit their membership lists on or before 19th March, 2017. The following Political Parties submitted their nomination rules by 2nd March, 2017 1. Progressive Party of Kenya 2. Ford-Kenya 3. Chama Cha Uzalendo 4. Democratic Congress 5. Kenya Social Congress 6. United Democratic Movement 7. Diligence Development Alliance 8. Ukweli Party 9. New Democrats 10. Democratic Party of Kenya 11. Party of Democratic Unity 12. Roots Party of Kenya 13. Maendeleo Democratic Party 14. Mzalendo Saba Saba 15. Alternative Leadership Party of Kenya 16. Kenya National Democratic Alliance 17. People’s Party of Kenya 18. Empowerment and Liberation Party 19. Vibrant Democratic Party 20. Kenya National Congress 21. NARC-Kenya 22. Kenya Patriots Party 23. Party of Independent Candidates of Kenya 24. National Rainbow Coalition 25. Restore and Build Kenya Party 26. Citizen Convention Party 27. Farmers Party of Kenya 28. Green Congress of Kenya Party 29. Devolution Party of Kenya 30. Amani National Congress 31. Safina Party of Kenya 32. People’s Empowerment Party 33. -

Kenya 2017: the Interim Elections? Justin Willis - Durham University Nic Cheeseman - University of Birmingham Gabrielle Lynch - University of Warwick

NOTE ACTUALITE 2 KENYA 2017: THE INTERIM ELECTIONS? Justin Willis - Durham University Nic Cheeseman - University of Birmingham Gabrielle Lynch - University of Warwick Juillet 2017 L’Observatoire de l’Afrique de l’Est (2017-2010) est un programme de recherche coordonné par le Centre d’Etude et de Documentation Econo- mique, Juridique et Sociale de Khartoum (MAEDI-CNRS USR 3123) et le Centre de Recherches Internationales de Sciences Po Paris. Il se situe dans la continuité de l’Observatoire de la Corne de l’Afrique qu’il remplace et dont il élargit le champ d’étude. L’Observatoire de l’Afrique de l’Est a vocation à réaliser et à diffuser largement des Notes d’analyse relatives aux questions politiques et sécuritaires contemporaines dans la région en leur offrant d’une part une perspective historique et d’autre part des fon- dements empiriques parfois négligées ou souvent difficilement accessibles. L’Observatoire est soutenu par la Direction Générale des Relations Inter- nationales et de la Stratégie (ministère des Armées français). Néanmoins, les propos énoncés dans les études et Observatoires commandés et pilo- tés par la DGRIS ne sauraient engager sa responsabilité, pas plus qu’ils ne reflètent une prise de position officielle du ministère de la Défense. Il s’appuie par ailleurs sur un large réseau de partenaires : l’Institut fran- çais des relations internationales, le CFEE d’Addis-Abeba, l’IFRA Nai- robi, le CSBA, LAM-Sciences Po Bordeaux, et le CEDEJ du Caire. Les notes de l’Observatoire de l’Afrique de l’Est sont disponibles en ligne sur le site de Sciences Po Paris. -

Federal Register/Vol. 65, No. 73/Friday, April 14, 2000/Notices

20160 Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 73 / Friday, April 14, 2000 / Notices OMB Approval Number: 3060±0481. 900 to renew. We anticipate that this Title: Application for Restricted Title: Application for Renewal of collection will be obsolete by the end of Radiotelephone Operator PermitÐ Private Radio Station License. calendar year 2000. Limited Use. Form Number: FCC 452R. Estimated costs associated with this Form Number: FCC 755. Type of Review: Extension of a collection including application and Type of Review: Extension of a currently approved collection. regulatory fees are approximately currently approved collection. Respondents: Individuals, State or $2,156,000. Respondents: Individuals. Local Governments, Business or other Number of Respondents: 1,000. OMB Approval Number: 3060±0104. Estimated Time Per Response: 20 For-Profit, Non-profit institutions. Title: Temporary Permit to Operate a Number of Respondents: 2,700. minutes (.33). Part 90 Radio Station. Estimated Time Per Response: 10 Total Annual Burden: 330 hours. minutes. Form Number: FCC 572. Needs and Uses: In accordance with Total Annual Burden: 448 hours. Type of Review: Extension of a the Communications Act, applicants Needs and Uses: Aviation Ground and currently approved collection. must possess certain qualifications in Marine Coast Radio Station licensees are Respondents: Businesses or other for- order to qualify for a radio operator required to apply for renewal of their profit; individuals or households; State license. The data will be used to radio station authorization every five or Local Governments; non-profit identify the individuals to whom the years. This short form renewal institutions. license is issued and to confirm that the application is generated by the Number of Recordkeepers: 2,000.