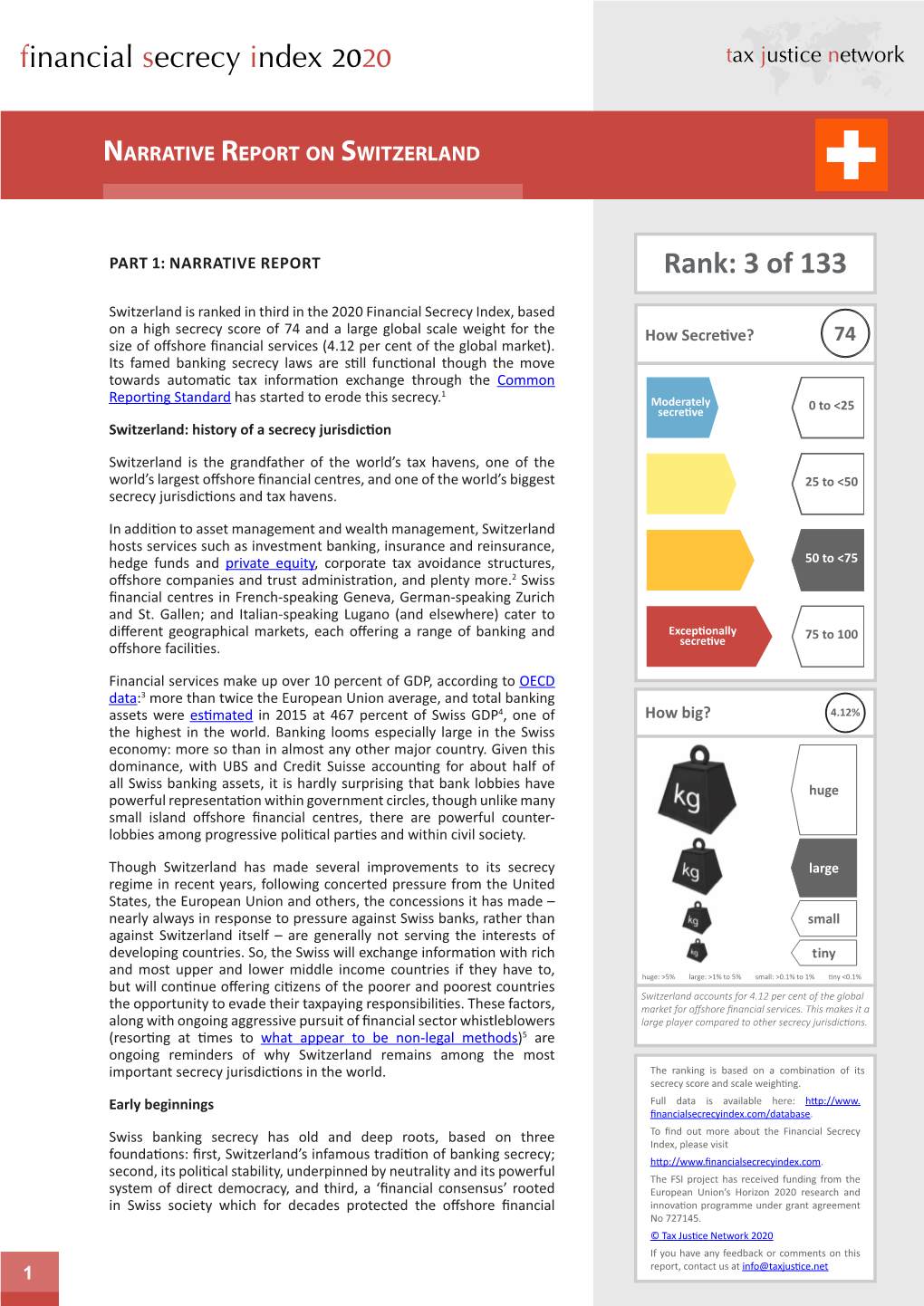

Switzerland.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Power of States and Business: Explaining

Ref. Ares(2017)5230581 - 26/10/2017 The power of states and business: Explaining transformative change in the fight against tax evasion and avoidance The Power of States and Business v2.0 19 September 2017 Document Details Work Package WP3 Lead Beneficiary University of Bamberg Deliverable ID D3.2 Date 05, 03, 2017 Submission 07, 28, 2017 Dissemination Level PU – Public / CO – Confidential / CI – Classified Information Version 1.0 Author(s) Lukas Hakelberg University of Bamberg Political Science [email protected] Acknowledgements The project “Combatting Fiscal Fraud and Empowering Regulators (COFFERS)” has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 727145. Document History Date Author Description 03-05-2017 Lukas Hakelberg First draft 19-09-2017 Lukas Hakelberg Second draft Page 2 of 52 The Power of States and Business v2.0 19 September 2017 Contents Document Details 2 Acknowledgements 2 Document History 2 Contents 3 Executive Summary 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Power in International Tax Policy 7 3. Post-Crisis Initiatives Against Tax Evasion and Avoidance 15 3.1 The Emergence of Multilateral AEI 16 3.1.1 Points of Departure: Savings Directive and Qualified Intermediary Program 16 3.1.2 Setting the Agenda: Left-of-Center Politicians and Major Tax Evasion Scandals 17 3.1.3 Towards New Rules: Legislative Initiatives in Europe and the US 20 3.1.4 The Role of Domestic Interest Groups: Tax Evaders and Financial Institutions 22 3.1.5 Reaching International Agreement: From Bilateral FATCA Deals to Multilateral AEI 25 3.2 Incremental Change in the Fight against Base Erosion and Profit Shifting 28 3.2.1 Points of Departure: Limiting Taxation at Source Through Transfer Pricing 28 3.2.2 Setting the Agenda: Starbuck’s and the Inclusion of Emerging Economies 30 3.2.3 Towards New Rules: The BEPS Report’s Ambiguous Recommendations 32 3.2.4 The Role of Interest Groups: In Defense of the Arm’s Length Principle 33 3.2.5 Reaching International Agreement? Ongoing EU-US Bargaining over BEPS 36 4. -

Narrative Report on Ireland

Financial Secrecy Index Ireland Narrative Report on Ireland Ireland is ranked at 47th position on the 2013 Financial Secrecy Index. This ranking is based on a combination of its Chart 1 - How Secretive? Moderately secrecy score and a scale weighting based on its share of the secretive 31-40 global market for offshore financial services. 41-50 Ireland has been assessed with 37 secrecy points out of a 51-60 potential 100, which places it into the moderately secretive 61-70 category at the bottom of the secrecy scale (see chart 1). 71-80 Ireland accounts for over 2 per cent of the global market for 81-90 offshore financial services, making it a small player compared with other secrecy jurisdictions (see chart 2). Exceptionally secretive 91-100 Part 1: Telling the story1 Chart 2 - How Big? Ireland as a financial centre: history and background Overview huge Ireland’s role as a secrecy jurisdiction or tax haven is based on two broad developments. The first, dating from 1956, is a regime of low tax rates and tax loopholes that have large encouraged transnational businesses to relocate – often small only on paper – to Ireland. The second is the role of the tiny Dublin-based International Financial Services Centre (IFSC), a Wild-West, deregulated financial zone set up in 1987 under the corrupt Irish politician Charles Haughey, which has striven particularly to host international ‘shadow banking’ activity2. Ireland’s secrecy score of 37 makes it one of the least secretive jurisdictions on our index: secrecy was never a central part of its ‘offshore’ offering. -

World Energy Perspectives Rules of Trade and Investment | 2016

World Energy Perspectives Rules of trade and investment | 2016 NON-TARIFF MEASURES: NEXT STEPS FOR CATALYSING THE LOW- CARBON ECONOMY ABOUT THE WORLD ENERGY COUNCIL The World Energy Council is the principal impartial network of energy leaders and practitioners promoting an affordable, stable and environmentally sensitive energy system for the greatest benefit of all. Formed in 1923, the Council is the UN- accredited global energy body, representing the entire energy spectrum, with over 3,000 member organisations in over 90 countries, drawn from governments, private and state corporations, academia, NGOs and energy stakeholders. We inform global, regional and national energy strategies by hosting high-level events including the World Energy Congress and publishing authoritative studies, and work through our extensive member network to facilitate the world’s energy policy dialogue. Further details at www.worldenergy.org and @WECouncil ABOUT THE WORLD ENERGY PERSPECTIVES – NON-TARIFF MEASURES: NEXT STEPS FOR CATALYSING THE LOW-CARBON ECONOMY The World Energy Perspective on Non-tariff Measures is the second report in a series looking at how an open global trade and investment regime concerning energy and environmental goods and services can foster the transition to a low-carbon economy. Building on the previous report on tariff barriers to environmental goods, this report highlights twelve significant non-tariff measures (NTMs) directly affecting the energy industry and investments in this sector. The World Energy Council has identified that these barriers greatly impact countries’ trilemma performance, the triple challenge of achieving secure, affordable and environmentally sustainable energy systems. Through this work, the Council seeks to inform policymakers as to what extent countries should address non-tariff measures to improve trade conditions, and eliminate unnecessary additional costs to trade, ultimately fostering national economic development. -

The Financial Secrecy Index: Shedding New Light on the Geography of Secrecy

The Financial Secrecy Index: Shedding New Light on the Geography of Secrecy Alex Cobham, Petr Janský, and Markus Meinzer Abstract Both academic research and public policy debate around tax havens and offshore finance typically suffer from a lack of definitional consistency. Unsurprisingly then, there is little agreement about which jurisdictions ought to be considered as tax havens—or which policy measures would result in their not being so considered. In this article we explore and make operational an alternative concept, that of a secrecy jurisdiction and present the findings of the resulting Financial Secrecy Index (FSI). The FSI ranks countries and jurisdictions according to their contribution to opacity in global financial flows, revealing a quite different geography of financial secrecy from the image of small island tax havens that may still dominate popular perceptions and some of the literature on offshore finance. Some major (secrecy-supplying) economies now come into focus. Instead of a binary division between tax havens and others, the results show a secrecy spectrum, on which all jurisdictions can be situated, and that adjustment lfor the scale of business is necessary in order to compare impact propensity. This approach has the potential to support more precise and granular research findings and policy recommendations. JEL Codes: F36, F65 Working Paper 404 www.cgdev.org May 2015 The Financial Secrecy Index: Shedding New Light on the Geography of Secrecy Alex Cobham Tax Justice Network Petr Janský Institute of Economic Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University in Prague Markus Meinzer Tax Justice Network A version of this paper is published in Economic Geography (July 2015). -

The Relationship Between MNE Tax Haven Use and FDI Into Developing Economies Characterized by Capital Flight

1 The relationship between MNE tax haven use and FDI into developing economies characterized by capital flight By Ali Ahmed, Chris Jones and Yama Temouri* The use of tax havens by multinationals is a pervasive activity in international business. However, we know little about the complementary relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in the developing world. Drawing on internalization theory, we develop a conceptual framework that explores this relationship and allows us to contribute to the literature on the determinants of tax haven use by developed-country multinationals. Using a large, firm-level data set, we test the model and find a strong positive association between tax haven use and FDI into countries characterized by low economic development and extreme levels of capital flight. This paper contributes to the literature by adding an important dimension to our understanding of the motives for which MNEs invest in tax havens and has important policy implications at both the domestic and the international level. Keywords: capital flight, economic development, institutions, tax havens, wealth extraction 1. Introduction Multinational enterprises (MNEs) from the developed world own different types of subsidiaries in increasingly complex networks across the globe. Some of the foreign host locations are characterized by light-touch regulation and secrecy, as well as low tax rates on financial capital. These so-called tax havens have received widespread media attention in recent years. In this paper, we explore the relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries, which are often characterized by weak institutions, market imperfections and a propensity for significant capital flight. -

8 May 2018 Tax Justice Network Response to the Questionnaire of The

8 May 2018 Tax Justice Network response to the questionnaire of the European Parliament Special Committee on Tax Crimes, Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance ("TAX3"), in advance of the hearing on "The fight against harmful tax practices within the European Union and abroad", scheduled for 15 May 2018: Why the TJN FSI lists 41 jurisdictions and the EU lists 9 jurisdictions at the moment? What differences in methodology do you notice? Could you explain the criteria used for the construction of the Financial Secrecy Index (FSI)? How could FSI be used for the implementation of anti-tax avoidance and even anti-money laundering rules in the EU and in the rest of the world? * The Tax Justice Network welcomes the opportunity to provide evidence to the European Parliament Special Committee on Tax Crimes, Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance ("TAX3"), and the energy which is now dedicated to addressing the major issues of international tax abuse which have been revealed by the Panama Papers, Paradise Papers, LuxLeaks and in a range of other investigative work and by our own research. For example, using a methodology developed by researchers at the International Monetary Fund, we estimate that global revenue losses to the profit shifting of multinational companies is in the order of $500 billion a year – and disproportionately felt by lower-income countries where those revenues are most badly needed. At the same time, EU member states are included among the biggest losers – and also among the most aggressive in seeking to disadvantage their neighbours. A similar pattern holds in respect of offshore tax evasion. -

Narrative Report on Panama

NARRATIVE REPORT ON PANAMA PART 1: NARRATIVE REPORT Rank: 15 of 133 Panama ranks 15th in the 2020 Financial Secrecy Index, with a high secrecy score of 72 but a small global scale weighting (0.22 per cent). How Secretive? 72 Coming within the top twenty ranking, Panama remains a jurisdiction of particular concern. Overview and background Moderately secretive 0 to 25 Long the recipient of drugs money from Latin America and with ample other sources of dirty money from the US and elsewhere, Panama is one of the oldest and best-known tax havens in the Americas. In recent years it has adopted a hard-line position as a jurisdiction that refuses to 25 to 50 cooperate with international transparency initiatives. In April 2016, in the biggest leak ever, 11.5 million documents from the Panama law firm Mossack Fonseca revealed the extent of Panama’s involvement in the secrecy business. The Panama Papers showed the 50 to 75 world what a few observers had long been saying: that the secrecy available in Panama makes it one of the world’s top money-laundering locations.1 Exceptionally 75 to 100 In The Sink, a book about tax havens, a US customs official is quoted as secretive saying: “The country is filled with dishonest lawyers, dishonest bankers, dishonest company formation agents and dishonest How big? 0.22% companies registered there by those dishonest lawyers so that they can deposit dirty money into their dishonest banks. The Free Trade Zone is the black hole through which Panama has become one of the filthiest money laundering sinks in the huge world.”2 Panama has over 350,000 secretive International Business Companies (IBCs) registered: the third largest number in the world after Hong Kong3 and the British Virgin Islands (BVI).4 Alongside incorporation of large IBCs, Panama is active in forming tax-evading foundations and trusts, insurance, and boat and shipping registration. -

Customs Value

What Every Member of the Trade Community Should Know About: Customs Value AN INFORMED COMPLIANCE PUBLICATION REVISED JULY 2006 Custom Value July, 2006 NOTICE: This publication is intended to provide guidance and information to the trade community. It reflects the position on or interpretation of the applicable laws or regulations by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) as of the date of publication, which is shown on the front cover. It does not in any way replace or supersede those laws or regulations. Only the latest official version of the laws or regulations is authoritative. Publication History First Issued: May, 1996 Revised July, 2006 PRINTING NOTE: This publication was designed for electronic distribution via the CBP website (http://www.cbp.gov/) and is being distributed in a variety of formats. It was originally set up ® in Microsoft Word97 . Pagination and margins in downloaded versions may vary depending upon which word processor or printer you use. If you wish to maintain the original settings, you may wish to download the .pdf version, which can then be printed using the freely ® available Adobe Acrobat Reader . 2 Custom Value July, 2006 PREFACE On December 8, 1993, Title VI of the North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act (Pub. L. 103-182, 107 Stat. 2057), also known as the Customs Modernization or “Mod” Act, became effective. These provisions amended many sections of the Tariff Act of 1930 and related laws. Two new concepts that emerge from the Mod Act are “informed compliance” and “shared responsibility,” which are premised on the idea that in order to maximize voluntary compliance with laws and regulations of U.S. -

Optimisation Through Offshore – Between Reality and Legality

MATEC Web of Conferences 342, 08009 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/202134208009 UNIVERSITARIA SIMPRO 2021 Optimisation through offshore – between reality and legality Bianca Cristina Ciocanea 11, Ioan Cosmin Pițu 2, Paraschiva Mihaela Luca3, and Dragoș Mihai Ungureanu4 1 Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Department of Doctoral Studies B-dul Victoriei Street 20, Sibiu, Romania 2 Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Department of Doctoral Studies B-dul Victoriei Street 20, Sibiu, Romania 3 Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Department of Doctoral Studies B-dul Victoriei Street 20, Sibiu, Romania 4 Spiru Haret University, Bucharest România Abstract. The study highlights the complete image of the characteristics regarding offshore areas, by taking into account the perspective to deploy new measures of fiscal transparency. The importance of such areas stems from the fact that world economies lose important sums of money, every year by default of taxes. This happens as a consequence of corporative international abuse of fiscal evasion and the relocation of the profit made by big companies. The sums resulted from erosion of national taxation bases, from fiscal evasion and fraud and other infringements connected with fiscal evasion (are often being transferred to offshore companies so that their illegal characteristics gets lost and after that to be reintroduced into the economic cycle. The main characteristics of these offshore centres is lack of transparency and cooperation with foreign authorities, fiscal and banking secrecy being considered the guarantee of the offshore areas, measurable variables, fleshes in indicators that reflect the secret degree for each state. Therefore, fighting against such practicies through offshore societies aims at enforcing some measures to enlarge transparency and for the regions do not cooperate there is no granting of fiscal deductibility for transactions that entail the transfer of sums to the respective regions. -

Taking Stock

Netzwerk Women in Development Europe Taking Stock The financial crisis and development from a feminist perspective WIDE’s Position paper on the global social, economic and environmental crisis Rue Hobbema 59 1000 Brussels Belgium Tel: +32 2 545 90 70 Fax: +32 2 512 73 42 [email protected] www.wide-network.org Authors Ursula Dullnig, Brita Neuhold, Traude Novy, Kathrin Pelzer, Edith Schnitzer, Barbara Schöllenberger, Claudia Thallmayer Editing Gerhild Perlaki-Straub, Hannah Golda This paper has been produced with the financial assistance of AECID, the European Union and HIVOS. The contents of the paper are the sole responsibility of WIDE and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the Funders. Publisher WIDE – Netzwerk Women in Development Europe Währingerstr. 2-4/22 1090 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 317 40 31, E-Mail: [email protected] http://www.wide-netzwerk.at Central Register number: 626905553 Copyright © January 2010 WIDE Any parts of this publication may be reproduced without the permission for educational and non- profit purposes if the source is acknowledged. WIDE would appreciate a copy of the text in which document is used or cited. 2 CONTENTS 1. WHY THIS FEMALE-ORIENTED PUBLICATION IS NECESSARY..................................................... 4 2. HIGHLIGHTS ON THE BACKDROP TO THE FINANCIAL CRISIS ..................................................... 7 3. THE PROTECTIVE SHIELD FOR THE FINANCIAL SECTOR AND ITS EFFECTS ON WOMEN ......... 11 4. FACTS AND FIGURES ABOUT THE FINANCIAL AND ECONOMIC CRISIS SINCE 2008 ................ 13 5. REVIEW: THE MEXICAN AND ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISES .......................................................... 18 6. WHO IS PAYING FOR THE CRISIS? ............................................................................................ 21 7. MEASURES AT THE INTERNATIONAL LEVEL ........................................................................... -

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS U.S. Customs Imports

STATE OF UTAH FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS Utah State Tax Commission 210 North 1950 West U.S. Customs Imports Salt Lake City, UT 84134 Q: How do I become licensed for use tax? A: To become licensed for use tax, you must complete Form TC-69, Utah State Business and Tax Registration. This form is found on our website at http://www.tax.utah.gov/forms/current/tc-69.pdf . Q: What if my purchases are intended for resale? A: Purchases of merchandise for resale are exempt from sales and use tax if the purchaser has a valid Q: What is Use Tax? sales tax account. If any or all of the imported items listed on the Purchases Subject to Use Tax worksheet A: Use tax is a tax on amounts paid or charged for you received were purchased for resale, indicate your purchases of tangible personal property and for sales tax number in your response to this letter, and certain services where sales tax was due but not provide documentation that the items purchased were charged. Use tax is not new, but has existed since intended for resale. Documentation may include July 1, 1937. In cases where a seller does not invoices showing the sale of those items, or of similar charge Utah sales tax, the purchaser is responsible items. to report and remit the tax. Use tax applies to both businesses and individuals. If any such purchases for resale are later withdrawn from inventory to be used by the purchaser, they must Q: Why is there such a thing as use tax? be reported on Line 4 of the Sales and Use Tax Return (Form TC-62S or TC-62M). -

Handbuch Investment in Germany

Investment in Germany A practical Investor Guide to the Tax and Regulatory Landscape in Germany 2016 International Business Preface © 2016 KPMG AG Wirtschaftsprüfungsgesellschaft, a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. Investment in Germany 3 Germany is one of the most attractive places for foreign direct investment. The reasons are abundant: A large market in the middle of Europe, well-connected to its neighbors and markets around the world, top-notch research institutions, a high level of industrial production, world leading manufacturing companies, full employment, economic and political stability. However, doing business in Germany is no simple task. The World Bank’s “ease of doing business” ranking puts Germany in 15th place overall, but as low as 107th place when it comes to starting a business and 72nd place in terms of paying taxes. Marko Gründig The confusing mixture of competences of regional, federal, and Managing Partner European authorities adds to the German gift for bureaucracy. Tax KPMG, Germany Numerous legislative changes have taken effect since we last issued this guide in 2011. Particularly noteworthy are the Act on the Modification and Simplification of Business Taxation and of the Tax Law on Travel Expenses (Gesetz zur Änderung und Ver einfachung der Unternehmensbesteuerung und des steuerlichen Reisekostenrechts), the 2015 Tax Amendment Act (Steueränderungsgesetz 2015), and the Accounting Directive Implementation Act (Bilanzrichtlinie-Umsetzungsgesetz). The remake of Investment in Germany provides you with the most up-to-date guide on the German business and legal envi- ronment.* You will be equipped with a comprehensive overview of issues concerning your investment decision and business Andreas Glunz activities including economic facts, legal forms, subsidies, tariffs, Managing Partner accounting principles, and taxation.