Redalyc.Politics of the Playground: the Spaces of Play of Robert Moses and Aldo Van Eyck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Plots Huge Land Deal with U.N. Garment Center Rezoning Shelved

20100614-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 6/11/2010 8:11 PM Page 1 REPORT HEALTH CARE HE’S THE MR. FIX-IT OF THE HOSPITAL BIZ And now he’s set his sights on Manhattan P. 15 ® Plus: a new acronym! P. 15 INSIDE VOL. XXVI, NO. 24 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM JUNE 14-20, 2010 PRICE: $3.00 TOP STORIES Gulf oil disaster Garment spills into NY lives center PAGE 2 High expectations for NYC’s tallest rezoning apartment tower PAGE 3 shelved Wall Street’s Protests, new views on summer bummer area’s value block plans IN THE MARKETS, PAGE 4 to decimate district Why LeBron James can have his cake BY ADRIANNE PASQUARELLI and eat it, too after months of protests, New York NEW YORK, NEW YORK, P. 6 City is quietly backing away from a se- ries of highly controversial proposals to rezone the 13-block garment center. Among those was a plan announced BUSINESS LIVES last April that would have taken the 9.5 million-square-foot manufacturing district and sewn it into a single 300,000-square-foot building on West 38th Clocking Street. $10B getty images “We always knew ANNUAL BY JEREMY SMERD that was kind of a CONTRIBUTION to the ridiculous proposal,” New York City in march 2003, executives at software company says Nanette Lepore, a economy Science Applications International Corp. were fashion designer who GOTHAM GIGS CityTime scrambling for a way out of a deal with the city to has been at the forefront of the battle to build a timekeeping system for its 167,000 munic- fight rezoning of the district. -

Politics of the Playground: the Spaces of Play of Robert Moses and Aldo Van Eyck Nicolás Stutzin

FIG 1 Jekerstraat, Amsterdam. Aldo Van Eyck, 1949. © Nicolás Stutzin, 2013 Politics of the Playground: the sPaces of Play of robert Moses and aldo van eyck Nicolás Stutzin Profesor, Facultad de Arquitectura, Arte y Diseño, Universidad Diego Portales Santiago, Chile As a machine for the production of common experiences, the playground was one of the most promoted urban spaces in the mid-twentieth century. Through the surprising parallel between Aldo van Eyck’s plan in Amsterdam and Robert Moses’s plan for New York, this article proves that such a politically correct program can be grounded on completely opposing world views; that is, that a common space can also be a place to experiment divergent political visions. Keywords · New York, Amsterdam, ideology, public space, city Some months after taking the position as Commissioner of the New York City Parks Department in 1934, Robert Moses inaugurated a series of nine playgrounds, the first of a massive initiative which would lead to the creation of nearly 700 new infant playgrounds in the course of 26 years during which he was in charge of the greatest public infrastructure developments of the city. Under Moses’s responsibility, between 1934 and 1960, the city achieved to add an average of one new playground every two weeks. In 1947, Aldo van Eyck, the then debutant architect of Amsterdam’s Public Infrastructure Department, was able to see the first of the over 700 small playgrounds he would design in residual spaces and parks throughout the city in the following 31 years and that would become a central part of his career. -

Chapter 4: Social Conditions

Chapter 4: Social Conditions A. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY This chapter addresses a variety of issues that support social conditions, including population and housing characteristics, community facilities and open spaces, and neighborhood character. The discussion of social conditions considers the entire MESA study area (depicted in Figure 3-1 in Chapter 3, above) with particular focus on the project corridor—the routes proposed for the various project alternatives—where the greatest potential for change would occur. Because none of the project alternatives have the potential to change social conditions in the secondary study area, where Build Alternatives 1 and 2 would add service along an existing subway line, this analysis is of the primary study area only. The analysis was conducted by first compiling existing data for population and housing, com- munity facilities and open spaces, and neighborhood character. The source for the population and housing data is the 1990 Census of Population and Housing. The inventory of community facilities is based on Community District Needs (1997) for Manhattan’s Community Boards, the Department of Parks and Recreation’s Property Lists (dated November 4, 1996), supplementary information provided by the various Community Boards within the study area, and the informa- tion gathered for the analysis of land use, zoning, and public policy in Chapter 3. The assessment of neighborhood character is based on information gathered for other chapters of this document, particularly including the analyses of land use (Chapter 3) and visual and aesthetic considerations (Chapter 6). After assessing the existing conditions in the study area, the expected changes in the future are considered, based on information compiled in Chapter 3. -

City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011)

City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011) Borou Block Lot Address Parcel Name gh 1 2 1 4 SOUTH STREET SI FERRY TERMINAL 1 2 2 10 SOUTH STREET BATTERY MARITIME BLDG 1 2 3 MARGINAL STREET MTA SUBSTATION 1 2 23 1 PIER 6 PIER 6 1 3 1 10 BATTERY PARK BATTERY PARK 1 3 2 PETER MINUIT PLAZA PETER MINUIT PLAZA/BATTERY PK 1 3 3 PETER MINUIT PLAZA PETER MINUIT PLAZA/BATTERY PK 1 6 1 24 SOUTH STREET VIETNAM VETERANS PLAZA 1 10 14 33 WHITEHALL STREET 1 12 28 WHITEHALL STREET BOWLING GREEN PARK 1 16 1 22 BATTERY PLACE PIER A / MARINE UNIT #1 1 16 3 401 SOUTH END AVENUE BATTERY PARK CITY STREETS 1 16 12 MARGINAL STREET BATTERY PARK CITY Page 1 of 1390 09/28/2021 City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011) Agency Current Uses Number Structures DOT;DSBS FERRY TERMINAL;NO 2 USE;WATERFRONT PROPERTY DSBS IN USE-TENANTED;LONG-TERM 1 AGREEMENT;WATERFRONT PROPERTY DSBS NO USE-NON RES STRC;TRANSIT 1 SUBSTATION DSBS IN USE-TENANTED;FINAL COMMITMNT- 1 DISP;LONG-TERM AGREEMENT;NO USE;FINAL COMMITMNT-DISP PARKS PARK 6 PARKS PARK 3 PARKS PARK 3 PARKS PARK 0 SANIT OFFICE 1 PARKS PARK 0 DSBS FERRY TERMINAL;IN USE- 1 TENANTED;FINAL COMMITMNT- DISP;LONG-TERM AGREEMENT;NO USE;WATERFRONT PROPERTY DOT PARK;ROAD/HIGHWAY 10 PARKS IN USE-TENANTED;SHORT-TERM 0 Page 2 of 1390 09/28/2021 City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011) Land Use Category Postcode Police Prct -

COMMUNITY BOARD 3 59 East 4Th Street - New York, NY 10003 Phone (212) 533 -5300 – [email protected]

Community/Borough Board Recommendation Pursuant to the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure Application #: Project Name: CEQR Number: Borough(s): Community District Number(s): Please use the above application number on all correspondence concerning this application SUBMISSION INSTRUCTIONS 1. Complete this form and return to the Department of City Planning by one of the following options: • EMAIL (recommended): Send email to [email protected] and include the following subject line: (CB or BP) Recommendation + (6-digit application number), e.g., “CB Recommendation #C100000ZSQ” • MAIL: Calendar Information Office, City Planning Commission, 120 Broadway, 31st Floor, New York, NY 10271 • FAX: to (212) 720-3488 and note “Attention of the Calendar Office” 2. Send one copy of the completed form with any attachments to the applicant's representative at the address listed below, one copy to the Borough President, and one copy to the Borough Board, when applicable. Docket Description: Applicant(s): Applicant’s Representative: Recommendation submitted by: Date of public hearing: Location: Was a quorum present? YES NO A public hearing requires a quorum of 20% of the appointed members of the board, but in no event fewer than seven such members. Date of Vote: Location: RECOMMENDATION Approve Approve With Modifications/Conditions Disapprove Disapprove With Modifications/Conditions Please attach any further explanation of the recommendation on additional sheets, as necessary. Voting # In Favor: # Against: # Abstaining: Total members appointed -

2014 City Council District Profiles 2021 Open Space Profiles

7 A-B-C 4-6-6 Express 1-2 MANHATTAN 2021 COMMUNITYQ DISTRICT 1-2 4-6-6 Express A-B-C-D Open Space 72nd St 4 2014 City Council District Profiles Profiles 6 5 N-R-W N-Q-R-W F-Q 66th St F R B-D-E 4-5-6-6 Legend A-C-E N Express 1-2 N-R-W 1/4 Mile 10thAve 59th St 8 Community Districts E-M ● Subway Stations N-Q-R-W 58th St n 9th Ave F City, State, and 57th St Federal Parkland B-D-F-M 56th St n 1 Madison Ave Playgrounds E-M 55th St A-C-E 4-6-6 Express n Schoolyards to Playgrounds 54th St n Public Plazas S 53rd St 17 52nd St Sutton Pl N n 41 Ave 7-7 Express 13 Swimming Pools 5th Ave 51st St 1-2-3 49th St n Dog Runs 8th Ave N-Q-R-W 50th St 18 7-7 48th St B-D-F-M ● Community Gardens 47th St Express ● F 5 46th St Recreation Centers 2 Ave 10 Vanderbilt Ave ● POPS S 45th St A-C-E ● K-12 Schools 7h Ave 4 6 Broadway 4-5-6-6 e 44th St v ● Public Libraries ExpressA 7-7 Express Vernon Blvd ● Hospitals & Clinics 43rd St 1-2-3 41st St 42nd St N-Q-R-W 9 20 Highest COVID-19 40th St B-D-F-M 7 12 Mortality Zip Codes 39th St 2019 Park Ave 44 Dr 14 F Roosevelt Dr ParklandE-M 1-2 6th Ave Lexington Ave 7-7 Express 1 Asser Levy Playground Court Sq 35th St 2 Augustus St. -

To Continue to Make Murray Hill a Highly Desirable Place to Live, Work E and Visit

2011–2012 A publication of the Murray Hill Neighborhood Association Murray Hill No. 4 …to continue to make Murray Hill a highly desirable place to live, work e and visit. Lif Winter One Enchanted Evening at the Polish Consulate Frederic Chopin, Richard Golub, and the Polish Consulate were the headliners at the Preservation and Design Award Evening on Thursday, October 13. Chopin provided the music, performed by pianist Domi- nic Meiman, in a room of surpassing splendor on the second floor of this impres- sive Beaux Arts mansion, which is now home to the Polish Consulate in New York. Before a sellout crowd of 180, Mr. Meiman played a generous Chopin program, beginning with the Grand Waltz No. 5, Op. 42, and finishing with what seemed Program Committee members, left to right: Irma Worrell Fisher, Dominic Meiman played Chopin. like étude after étude after Enid Klass, Susan Demmet and Minor Bishop. Rear right, former Photo: Sami Steigmann étude. Meanwhile, the MHNA President Steve Weingrad. painted cherubs and angels Photo: Sami Steigmann amidst the room’s gold latticework seemed to look down in rapt attention. Minor Bishop praised the meticu- “What a neighborhood!” lousness of the Polish restoration. Mrs. Junczyk- Ziomecka “In cleaning the entire building, exclaimed in this is what actually preserved it,” accepting the Mr. Bishop said. “From windows to award. When steelwork to stone, this is a heroic she became example of what preservation is Consul General and provides a chance to see what a year and a half this building really looked like, the ago, she admitted that actual color of the stone… I applaud she had looked all over their effort.” Manhattan for a place to Susan Demmet and Irma Wor- live. -

Fiscal Year 2019 Annual Report on Park Maintenance

Annual Report on Park Maintenance Fiscal Year 2019 City of New York Parks & Recreation Bill de Blasio, Mayor Mitchell J. Silver, FAICP, Commissioner Annual Report on Park Maintenance Fiscal Year 2019 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 Understanding Park Maintenance Needs ............................................................................... 1 How Parks are Maintained ...................................................................................................... 2 About the Data Used in this Report ....................................................................................... 3 Data Caveats .......................................................................................................................... 5 Report Column Definitions and Calculations ........................................................................... 5 Tables ...................................................................................................................................... Table 1 – Park-Level Services ............................................................................................ 8 Table 2 – Sector-Level Services ........................................................................................98 Table 3 – Borough and Citywide Work Orders ...................................................................99 Table 4 – Borough and Citywide-Level Services Not Captured in Work -

2014 City Council District Profiles Perfiles Del

7 A-B-C 4-6-6 Express 1-2 MANHATTAN Perfiles DISTRITOQ COMUNITARIO 1-2 4-6-6 Express A-B-C-D del Espacio 72nd St 4 2014 City Council District Profiles Abierto 2021 6 5 N-R-W N-Q-R-W F-Q 66th St F R B-D-E 4-5-6-6 Leyenda A-C-E N Express 1-2 N-R-W 1/4 de Milla 10thAve 59th St 8 Distritos Comunitarios E-M ● Estaciones de Metro N-Q-R-W 58th St n 9th Ave F Área Verde Municipal, 57th St Estatal y Federal B-D-F-M 56th St n 1 Madison Ave Patios de Recreo E-M 55th St A-C-E 4-6-6 Express n Patios de Recreo 54th St Escolares a Públicos 53rd St 17 S 52nd St Sutton Pl N n Plazas41 Ave Públicas 7-7 Express 13 5th Ave 51st St 1-2-3 49th St n Piscinas 8th Ave N-Q-R-W 50th St 18 7-7 48th St n B-D-F-M Parques para Perros 47th St Express ● Jardines ComunitariosF 5 46th St 2 Ave 10 ● Centros de Recreación S Vanderbilt Ave 45th St A-C-E ● Espacios Públicos de 7h Ave 4 6 Broadway 4-5-6-6 e 44th St Propiedad Privada v ExpressA 7-7 Express ● Escuelas de K-12 Vernon Blvd 43rd St 1-2-3 41st St 42nd St ● Bibliotecas Públicas N-Q-R-W 9 40th St ● Hospitales y Clínicas B-D-F-M 7 12 39th St 2019 20 Códigos Postales Park Ave 44 Dr con Mortalidad Más Alta 14 F Roosevelt Dr E-M 1-2 6th Ave del COVID-19 Lexington Ave 7-7 Express Court Sq 35th St A-C-E 4-6-6 Express Área Verde N-Q-R-W G S 34th St 5 11 St 1 Asser Levy Playground 15 Fifth St 33rd St 2 Augustus St. -

2019 Agency Annual Concession Plan

CITY OF NEW YORK AGENCY ANNUAL CONCESSION PLAN FOR FISCAL YEAR 2019 (CITYWIDE) FOR NEW EXPIRATION FOR NEW ANTICIPATED ANNUAL CONCESSION LOCATION OF CONCESSION/BRIEF DESCRIPTION FOR EFFECTIVE DATE AFFECTED CONCESSION CONCESSIONS, BUSINESS ADDRESS OF CONCESSION CONCESSION OR DATE OF AFFECTED CONCESSIONS, CONCESSION SIGNIFICANT/NON- AGENCY ID/PERMIT CURRENT CONCESSIONAIRE NAME CONCESSIONS PLANNED FOR OF CURRENT COMMUNITY SOLICITATION ANTICIPATED CURRENT CONCESSIONAIRE STATUS FACILITY TYPE CURRENT BOROUGH(S) ANTICIPATED REVENUE FOR FISCAL SIGNIFICANT NUMBER SOLICITATION/INITIATION IN FISCAL YEAR 2019 CONCESSION BOARD(S) METHOD RELEASE DATE OF CONCESSION CONCESSION TERM YEAR 2019 SOLICITATION Sunset Park at 41st between 6th and 7th Avenues and at 44th DPR B087-C N/A N/A Plan to Initiate Mobile Food Cart Notice to Proceed 12/31/2022 Brooklyn 7 Request for Bids N/A 5 Years $16,500 Non-significant between 5th and 6th Avenues DPR B100-MT N/A N/A Seth Low Playground Plan to Initiate Mobile Food Truck Notice to Proceed 12/31/2022 Brooklyn 11 Request for Bids N/A 5 Years $139,500 Non-significant 173 Main Street, 3rd Floor Ossining, Washington Park (J.J. Byrne Playground) on 5th Ave. between 3rd DPR B111-FM-O Zeltsman Associates, Inc d.b.a Down to Earth Markets Continuing Farmers Market 5/11/2016 5/10/2021 Brooklyn 6 Request for Proposals N/A N/A $1,145 Non-significant NY 10562 and 4th streets 2453 64th Street, Apt. B12, Washington Park (J.J. Byrne Playground) on 5th Ave. between 3rd DPR B111-MT Muradova, Yulduz Continuing Mobile Food Truck 7/30/2016 -

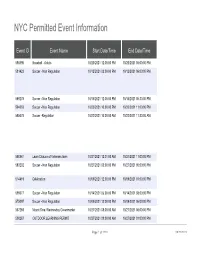

NYC Permitted Event Information

NYC Permitted Event Information Event ID Event Name Start Date/Time End Date/Time 598895 Baseball - Adults 10/20/2021 12:00:00 PM 10/20/2021 05:00:00 PM 581423 Soccer - Non Regulation 10/12/2021 03:00:00 PM 10/12/2021 06:00:00 PM 589278 Soccer - Non Regulation 10/15/2021 12:00:00 PM 10/15/2021 05:30:00 PM 594063 Soccer - Non Regulation 10/26/2021 10:00:00 PM 10/26/2021 11:00:00 PM 585078 Soccer -Regulation 10/22/2021 10:00:00 AM 10/22/2021 11:30:00 AM 590861 Lawn Closure of Veterans lawn 10/21/2021 12:01:00 AM 10/21/2021 11:00:00 PM 583232 Soccer - Non Regulation 10/27/2021 03:00:00 PM 10/27/2021 05:00:00 PM 514419 Celebration 10/09/2021 12:00:00 PM 10/09/2021 01:00:00 PM 599077 Soccer - Non Regulation 10/14/2021 06:00:00 PM 10/14/2021 08:00:00 PM 575097 Soccer - Non Regulation 10/09/2021 12:00:00 PM 10/09/2021 06:00:00 PM 557269 Mount Sinai Wednesday Greenmarket 10/27/2021 08:00:00 AM 10/27/2021 06:00:00 PM 598287 OUTDOOR LEARNING PERMIT 10/27/2021 09:00:00 AM 10/27/2021 01:00:00 PM Page 1 of 1228 09/29/2021 NYC Permitted Event Information Event Agency Event Type Event Borough Parks Department Sport - Adult Bronx Parks Department Sport - Youth Brooklyn Parks Department Sport - Youth Staten Island Parks Department Sport - Adult Brooklyn Parks Department Sport - Youth Manhattan Parks Department Special Event Manhattan Parks Department Sport - Youth Manhattan Parks Department Special Event Manhattan Parks Department Sport - Youth Brooklyn Parks Department Sport - Youth Queens Street Activity Permit Office Farmers Market Manhattan Parks Department Special Event Manhattan Page 2 of 1228 09/29/2021 NYC Permitted Event Information Event Location Event Street Side Van Cortlandt Park: Stadium-Baseball-01 Bush Terminal Park: Soccer-02 ,Bush Terminal Park: Soccer-03 ,Calvert Vaux Park: Soccer- 01 ,Calvert Vaux Park: Soccer-02 ,Kaiser Park: Football-01 ,Betsy Head Park: Football-02 ,Bushwick Inlet Park: Soccer-01 ,St. -

Chapter 4: Open Space

Open Space 4.1 Introduction This chapter assesses the potential effects on open space that could result from the Proposed Action. Open space is defined as publicly or privately owned land that is publicly accessible and operates, functions, or is available for leisure, play, or sport, or set aside for the protection and/or enhancement of the natural environment. Open space that is used for sports, exercise, or active play is classified as active, while open space that is used for relaxation, such as sitting or strolling, is classified as passive. According to the 2014 CEQR Technical Manual, an analysis of open space is conducted to determine whether a proposed action would have a direct impact resulting from the elimination or alteration of open space and/or an indirect impact resulting from overtaxing available open space. The Proposed Action, discussed in Section 1.4 of Chapter 1 “Project Description,” comprises zoning text and zoning map amendments to establish the East Midtown Subdistrict within an approximately 78-block area within the East Midtown neighborhood of Manhattan. The Proposed Action is intended to reinforce the area’s standing as a premiere central business district, support the preservation of landmarks, and provide for public realm improvements, such as pedestrian plazas, shared streets, and a redesigned Park Avenue Median that would be new open space resources. Under the Reasonable Worst-Case Development Scenario (RWCDS), the Proposed Action is projected to result in approximately 13,394,777 gross square feet (gsf) of office floor area, 601,899 gsf of retail floor area and 237,841 gsf of residential floor area on 16 Projected Development Sites.