1 Why Media Researchers Don't Care About Teletext

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Imbalances: Communications and The

"INFORMATION IMBALANCES": Communications and the Developing World Shashi Tharoor* A Latin American newspaper ignores a historic economic conference between the under-developed nations and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries in order to play up the opening of a New York photographic exhibition by Caroline Kennedy. On a single day a newspaper in India devotes three times the wordage to Princess Anne's fall from a horse than it has accorded neighboring Sri Lanka Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike in a week. The South China Morning Post prints Peking-watcher stories written in Hong Kong by New York Times correspondents whose copy is cabled back after being edited in the United States. A Kuwaiti learns about political developments in Thailand from reports by a transnational' news agency based in New York. These are "information imbalances," the international media's latest cause for concern, a concept referring to the disequilibria in the structure of communication that result in the preponderance of Western, and specifically American, sources of information in the world today. The post-World War II enthusiasm for democratic principles, which caused the ideals of a free press to be enshrined almost univer- sally, has abated considerably in recent years. With the Third World's ' ' 2 acquisition of an "international class-consciousness these principles the 1975-76 *Shashi Tharoor (MA 1976), a candidate for the MALD at The Fletcher School, won Kripalani Award forJournalism in India. the big four news agencies 1. The numerous authorities consulted differ on whether to term This article uses both locutions, (Reuters, AP, UPI, AFP) "multinationals" or "transnationals." that these agencies are not "inter- interchangeably; the only important distinction to note is national frontiers. -

• United Nations • UN Millenium Development Goals

• United Nations • The Bretton Woods Institutions http://www.un.org http://www.chebucto.ns.ca/Current/P7/b wi/cccbw.html • UN Millenium Development Goals http://www.developmentgoals.org/ News • The Economist • MUNweb http://www.economist.co.uk/ http://www.munweb.org/ • Foreign Affairs • UN Official MUN website http://www.foreignaffairs.org/ http://www.un.org/cyberschoolbus/mod elun/ • Associated Press http://www.ap.org/ • UN System - Alphabetic Index of Websites of the United Nations • Russian News Agency System of Organizations http://www.tass.net/ http://www.unsystem.org/ • Interfax International Group • United Nations Development http://www.interfax-news.com/ Programme http://www.undp.org/ • British Broadcasting Corporation http://news.bbc.co.uk/ • UN Enviroment Programme http://www.unep.org/ • Reuters. Know. Now. http://www.reuters.com/ • Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights • Agencia EFE http://www.ohchr.org/english/ http://www.efe.es/ • International Criminal Court • Agence France Presse http://www.iccnow.org/ www.afp.com • International Criminal Tribunal for • El Mundo the former Yugoslavia http://www.elmundo.es http://www.un.org/icty/ • Aljazeera International English • United Nations Bibliographic Edition Information System http://www.aljazeera.com/ http://unbisnet.un.org/ • Foreign Affairs • International Criminal Tribunal for http://www.foreignaffairs.org/ Rwanda http://www.ictr.org/ • Associated Press http://www.ap.org/ • International Court of Justice http://www.icj-cij.org/ • Russian News Agency http://www.tass.net/ • World Bank Group http://www.worldbank.org/ • Interfax International Group http://www.interfax-news.com/ • European Union http://europa.eu.int/ • British Broadcasting Corporation http://news.bbc.co.uk/ • World Trade Organization http://www.wto.org/ • Reuters. -

Earning Astana Yellow Jerseys in a Corporate Governance Race: Engaging External Partners in Communications in Kazakhstan

Earning Astana yellow Jerseys in a Corporate Governance Race: Engaging External Partners in Communications in Kazakhstan What do corporate governance and bicycle racing have in common? Frankly, not much. But the IFC Central Asia Corporate Governance Project team felt like cycling champions after our success in raising awareness about corporate governance in Kazakhstan. The corporate governance “race” in Kazakhstan started in 2006 in Almaty when a team of 11 people got together to launch the project. Just as the Astana cycling team retains its first place in the world ranking, subsequently reinforced by the victory of Alberto Contador in the Tour de France, our project team came out winners in helping corporate governance become an important topic in Kazakhstan. In this SmartLesson we would like to share how the project partnered with international coaches, local experts, and government bodies to promote corporate governance through publications, annual conferences, and seminars for mass media representatives in Kazakhstan. Background competitiveness and sustainability of the national Kazakhstan is located in the heart of the Eurasian economy, relying on corporate governance principles. continent at the crossroads of East and West. Prime Minister Karim Massimov also participated When the project started operations, not many of in a corporate governance awareness conference in the region’s businesspeople knew what corporate February 2007 in the Kazakhstani capital, Astana, governance was. IFC’s communications objective thereby greatly raising the profile of the topic through was to widely spread the word about corporate the accompanying press coverage. In spring 2007, governance, convince policymakers to create a full Senate hearings on the competitiveness of the favorable legislative framework, and—the most economy included invited experts on corporate important task—inspire joint-stock companies and governance. -

Guidelines on Communications Strategies for the Transition from Analogue to Digital Terrestrial Broadcasting

2014-2017 Guidelines ITU-D Study Group 1 Question 8/1 International Telecommunication Union Telecommunication Development Bureau Guidelines on Place des Nations CH-1211 Geneva 20 Communications Switzerland www.itu.int Strategies for the Transition from Analogue to Digital Terrestrial Broadcasting 6th Study Period 2014-2017 EXAMINATION OF STRATEGIES AND METHODS OF MIGRATION FROM ANALOGUE TO DIGITAL TERRESTRIAL BROADCASTING AND IMPLEMENTATION OF NEW SERVICES OF NEW AND IMPLEMENTATION BROADCASTING TERRESTRIAL DIGITAL TO ANALOGUE FROM AND METHODS OF MIGRATION OF STRATEGIES EXAMINATION ISBN 978-92-61-24801-7 QUESTION 8/1: QUESTION 9 7 8 9 2 6 1 2 4 8 0 1 7 Printed in Switzerland Geneva, 2017 07/2017 International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Telecommunication Development Bureau (BDT) Office of the Director Place des Nations CH-1211 Geneva 20 – Switzerland Email: [email protected] Tel.: +41 22 730 5035/5435 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Deputy to the Director and Infrastructure Enabling Innovation and Partnership Project Support and Knowledge Director,Administration and Environmnent and Department (IP) Management Department (PKM) Operations Coordination e-Applications Department (IEE) Department (DDR) Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Tel.: +41 22 730 5784 Tel.: +41 22 730 5421 Tel.: +41 22 730 5900 Tel.: +41 22 730 5447 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Africa Ethiopia Cameroon Senegal Zimbabwe International Telecommunication Union internationale des Union internationale des International Telecommunication Union (ITU) télécommunications (UIT) télécommunications (UIT) Union (ITU) Regional Office Bureau de zone Bureau de zone Area Office P.O. -

Filing Port Code Filing Port Name Manifest Number Filing Date Next

Filing Port Call Sign Next Foreign Trade Official Vessel Type Total Dock Code Filing Port Name Manifest Number Filing Date Next Domestic Port Vessel Name Next Foreign Port Name Number IMO Number Country Code Number Agent Name Vessel Flag Code Operator Name Crew Owner Name Draft Tonnage Dock Name InTrans 5204 WEST PALM BEACH, FL 5204-2021-00375 1/14/2021 - TROPIC MIST FREEPORT, GRAND BAHAMA I J8NZ 8204183 BS 3 400204 TROPICAL SHIPPING CO. VC 333 TROPICAL SHIPPING AND CONSTRUCTION COMPANY LTD. 14 TROPICAL SHIPPING AND CONSTRUCTION 15'0" 548 PORT OF PALM BEACH BERTHS NOS. 8 & 9 (2012) DLX 1803 JACKSONVILLE, FL 1803-2021-00350 1/14/2021 - SLNC MAGOTHY (EX. NORFLOK) GUANTANAMO BAY WDI3067 9418975 CU 3 1262669 CB AGENCIES US 310 ARGENT MARINE OPERATIONS, INC. 17 HS MAGOTHY LLC 27'0" 6089 BLOUNT ISLAND - BERTHS 4 - 6 LY 4601 NEW YORK/NEWARK AREA 4601-2021-01122 1/14/2021 BALTIMORE, MD MAERSK VILNIUS - 9V8503 9408956 - 6 395877 NORTON LILLY INTERNATIONAL SG 310 A.P. MOLLER MAERSK A/S 22 A.P. MOLLER SINGAPORE PTE, LTD 28'3" 8602 PORT NEWARK CONTAINER TERM (PNCT) BERTHS 53, 55, 57, 59 DFL 5301 HOUSTON, TX 5301-2021-01995 1/14/2021 - CHEMSTAR TIERRA ARATU 3EXM9 9827451 BR 2 49547-18 GENERAL STEAMSHIP INC. PA 112 IINO MARINE SERVICE CO., LTD. 24 SIETEMAR, S.A. 34'0" 6474 KINDER MORGAN GALENA PARK L 4601 NEW YORK/NEWARK AREA 4601-2021-01121 1/14/2021 NORFOLK, VA MELCHIOR SCHULTE - 9V3053 9676723 - 6 399740 Turkon America SG 310 BEACH ROAD PARK SHIPPING CO. -

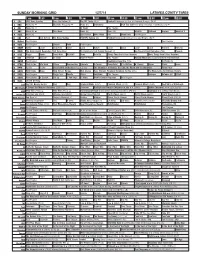

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and The

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and the Commodification of Reality, 1927-1945 By Joseph E.J. Clark B.A., University of British Columbia, 1999 M.A., University of British Columbia, 2001 M.A., Brown University, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May, 2011 © Copyright 2010, by Joseph E.J. Clark This dissertation by Joseph E.J. Clark is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Susan Smulyan, Co-director Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Philip Rosen, Co-director Recommended to the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Lynne Joyrich, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Dean Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Joseph E.J. Clark Date of Birth: July 30, 1975 Place of Birth: Beverley, United Kingdom Education: Ph.D. American Civilization, Brown University, 2011 Master of Arts, American Civilization, Brown University, 2004 Master of Arts, History, University of British Columbia, 2001 Bachelor of Arts, University of British Columbia, 1999 Teaching Experience: Sessional Instructor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies, Simon Fraser University, Spring 2010 Sessional Instructor, Department of History, Simon Fraser University, Fall 2008 Sessional Instructor, Department of Theatre, Film, and Creative Writing, University of British Columbia, Spring 2008 Teaching Fellow, Department of American Civilization, Brown University, 2006 Teaching Assistant, Brown University, 2003-2004 Publications: “Double Vision: World War II, Racial Uplift, and the All-American Newsreel’s Pedagogical Address,” in Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson, eds. -

NPDES WW Power Plant and Industrial with and Without Stormwater

COLOR KEY: Industry not covered by 40 CFR?? Does not appear to be but Double- Look Into. These may not be covered by 40 CFR. Check to be sure. Not appear to be Not sure. Not familiar enough with industry to Steam Electric Turbine. know if they have a Steam Electric Turbine. 40 CFR covers:(vii) Steam electric power generating facilities, including coal handling sites; Needs SW Permit? Is a Power plant, does not have a SW permit but DOES Needs SW Permit? Check to see if there are SW Not a Power Plant - have SW language in it. We need to outfalls. May need SW Permit. Ask the Region if Needs NPDES SW evaluate these. Ask the Region. they have been there… Permit? Look into. Has SW permit but may have coal pile on site - not covered in SW General Permit? Look at site and permit. Contact Region Has SW General or Individual Permit. No Action SW permit expired Has Ken Power plant? Permit Owner Facility County Region Class Expires SW permit SW text? Comments / Action Power Plant? Reviewed? SW language in permit NC0000396 NC0000396 Progress Energy Carolinas, Inc. Asheville Steam Electric Power Plant Buncombe Asheville Major 12/31/2010 none YES Power Plant - Needs NPDES SW Permit? Power plant yes Visual*, 2/yrVisual, 2/yr NC0003433 NC0003433 Progress Energy Carolinas, Inc. Cape Fear Steam Electric Power Plant Chatham Raleigh Major 7/31/2011 none YES Power Plant - Needs NPDES SW Permit? Power plant yes none NC0005363 NC0005363 Progress Energy Carolinas, Inc. Weatherspoon Steam Electric Plant Robeson Fayetteville Minor 7/31/2009 none YES Power Plant - Needs NPDES SW Permit? Power plant yes Visual, TSS, O&G, As, Cu, Fe, Hg, Se, pH: all 2/yrVisual, 2/yr NC0038377 NC0038377 Progress Energy Carolinas, Inc. -

BBC TV\S Panorama, Conflict Coverage and the Μwestminster

%%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and WKHµ:HVWPLQVWHU FRQVHQVXV¶ David McQueen This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. %%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and the µ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 µLet nation speak peace unto nation¶ RIILFLDO%%&PRWWRXQWLO) µQuaecunque¶>:KDWVRHYHU@(official BBC motto from 1934) 2 Abstract %%&79¶VPanoramaFRQIOLFWFRYHUDJHDQGWKHµ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen 7KH%%&¶VµIODJVKLS¶FXUUHQWDIIDLUVVHULHVPanorama, occupies a central place in %ULWDLQ¶VWHOHYLVLRQKLVWRU\DQG\HWVXUSULVLQJO\LWLVUHODWLYHO\QHJOHFWHGLQDFDGHPLF studies of the medium. Much that has been written focuses on Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRI armed conflicts (notably Suez, Northern Ireland and the Falklands) and deals, primarily, with programmes which met with Government disapproval and censure. However, little has been written on Panorama¶VOHVVFRQWURYHUVLDOPRUHURXWLQHZDUUeporting, or on WKHSURJUDPPH¶VPRUHUHFHQWKLVWRU\LWVHYROYLQJMRXUQDOLVWLFSUDFWLFHVDQGSODFHZLWKLQ the current affairs form. This thesis explores these areas and examines the framing of war narratives within Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRIWKH*XOIFRQIOLFWV of 1991 and 2003. One accusation in studies looking beyond Panorama¶VPRUHFRQWHQWLRXVHSLVRGHVLVWKDW -

Drama Directory

2015 UPDATE CONTENTS Acknowlegements ..................................................... 2 Latvia ......................................................................... 124 Introduction ................................................................. 3 Lithuania ................................................................... 127 Luxembourg ............................................................ 133 Austria .......................................................................... 4 Malta .......................................................................... 135 Belgium ...................................................................... 10 Netherlands ............................................................. 137 Bulgaria ....................................................................... 21 Norway ..................................................................... 147 Cyprus ......................................................................... 26 Poland ........................................................................ 153 Czech Republic ......................................................... 31 Portugal ................................................................... 159 Denmark .................................................................... 36 Romania ................................................................... 165 Estonia ........................................................................ 42 Slovakia .................................................................... 174 -

Broadcasting & Convergence

1 Namnlöst-2 1 2007-09-24, 09:15 Nordicom Provides Information about Media and Communication Research Nordicom’s overriding goal and purpose is to make the media and communication research undertaken in the Nordic countries – Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden – known, both throughout and far beyond our part of the world. Toward this end we use a variety of channels to reach researchers, students, decision-makers, media practitioners, journalists, information officers, teachers, and interested members of the general public. Nordicom works to establish and strengthen links between the Nordic research community and colleagues in all parts of the world, both through information and by linking individual researchers, research groups and institutions. Nordicom documents media trends in the Nordic countries. Our joint Nordic information service addresses users throughout our region, in Europe and further afield. The production of comparative media statistics forms the core of this service. Nordicom has been commissioned by UNESCO and the Swedish Government to operate The Unesco International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media, whose aim it is to keep users around the world abreast of current research findings and insights in this area. An institution of the Nordic Council of Ministers, Nordicom operates at both national and regional levels. National Nordicom documentation centres are attached to the universities in Aarhus, Denmark; Tampere, Finland; Reykjavik, Iceland; Bergen, Norway; and Göteborg, Sweden. NORDICOM Göteborg -

Connecting Leading Candidates to the World's Finest Science Jobs, Events

Connecting leading candidates to the world’s finest science jobs, events and other career development resources Click on the to navigate the pages PROMOTE YOUR RECRUITMENT ORGANIZATION EVENTS FILL YOUR VACANCIES BRANDED CONTENT & PROMOTE YOUR EVENTS Our Audience & Reach NATIVE ADVERTISING Multichannel marketing Job listing packages Custom Advertorials Nature Events Guide Employer Profile & Index Profile MULTICHANNEL MARKETING Custom Podcasts & Webcasts EXHIBIT AT CAREER EVENTS Banners *optimized targeting* Case Studies Careers Live Emails London • New York • Singapore Print EDITORIAL FEATURES Spotlights and Career Guides REGIONAL RECRUITMENT Salary Survey, Graduate Survey, Scientist At Work photo competition 2019 OTHER CALENDAR ABOUT US RESOURCES EDITORIAL CALENDAR NATURE CAREERS SPECS Print Specs NATURE RESEARCH Banner Specs Third Party Email Specs Alerts Specs SPRINGER NATURE TERMS & CONDITIONS CONTACT US UK/ROW: +44 (0)20 7843 4961 US: +1 212 726 9270 [email protected] 2 | Nature Careers 2019 Media Options RECRUITMENT PROMOTIONS EVENTS CALENDAR ABOUT US OTHER RESOURCES RECRUITMENT FILL YOUR VACANCIES Our Audience & Reach Job listing packages MULTICHANNEL MARKETING Banners *optimized targeting* Email Print REGIONAL RECRUITMENT 3 | Recruitment | Nature Careers 2019 Media Options RECRUITMENT PROMOTIONS EVENTS CALENDAR ABOUT US OTHER RESOURCES OUR AUDIENCE & REACH Nature Careers Nature Careers is the global career resource, jobs board and events directory for scientists. It is brought to you by Springer Nature, a leading publisher