The Blood Gospels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tensor Simrank for Heterogeneous Information Networks

Tensor SimRank for Heterogeneous Information Networks Ben Usman Ivan Oseledets Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, Novaya St., 100, Skolkovo, 143025, Russian Novaya St., 100, Skolkovo, 143025, Russian Federation Federation Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Institute of Numerical Mathematics, Russian Institutskiy Lane 9, Dolgoprudny, Moscow, Academy of Sciences, Gubkina St., 8, Moscow, 141700, Russian Federation 119333 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT A Type of: devised structured activity Instance of: candidate KB completeness node, clarifying We propose a generalization of SimRank similarity measure collection type, type of object, type of temporally stuff-like for heterogeneous information networks. Given the informa- thing tion network, the intraclass similarity score s(a; b) is high if Subtypes: board game, brand name game, card game, the set of objects that are related with a and the set of ob- child's game, coin-operated game, dice game, electronic jects that are related with b are pair-wise similar according game, fantasy sports, game for two or more people, game to all imposed relations. of chance, guessing game, memory game, non-competitive game, non-team game, outdoor game, party game, puzzle Categories and Subject Descriptors game, role-playing game, sports game, table game, trivia [Information systems]: Retrieval models and ranking{ game, word game Similarity measures Instances: ducks and drakes, ultimate frisbee, darts, pachinko, Crossword -

(Books): Dark Tower (Comics/Graphic

STEPHEN KING BOOKS: 11/22/63: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook 1922: PB American Vampire (Comics 1-5): Apt Pupil: PB Bachman Books: HB, pb Bag of Bones: HB, pb Bare Bones: Conversations on Terror with Stephen King: HB Bazaar of Bad Dreams: HB Billy Summers: HB Black House: HB, pb Blaze: (Richard Bachman) HB, pb, CD Audiobook Blockade Billy: HB, CD Audiobook Body: PB Carrie: HB, pb Cell: HB, PB Charlie the Choo-Choo: HB Christine: HB, pb Colorado Kid: pb, CD Audiobook Creepshow: Cujo: HB, pb Cycle of the Werewolf: PB Danse Macabre: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Half: HB, PB, pb Dark Man (Blue or Red Cover): DARK TOWER (BOOKS): Dark Tower I: The Gunslinger: PB, pb Dark Tower II: The Drawing Of Three: PB, pb Dark Tower III: The Waste Lands: PB, pb Dark Tower IV: Wizard & Glass: PB, PB, pb Dark Tower V: The Wolves Of Calla: HB, pb Dark Tower VI: Song Of Susannah: HB, PB, pb, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Tower VII: The Dark Tower: HB, PB, CD Audiobook Dark Tower: The Wind Through The Keyhole: HB, PB DARK TOWER (COMICS/GRAPHIC NOVELS): Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1-7 of 7 Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born ‘2nd Printing Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Long Road Home: Graphic Novel HB (x2) & Comics 1-5 of 5 Dark Tower: Treachery: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1–6 of 6 Dark Tower: Treachery: ‘Midnight Opening Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Fall of Gilead: Graphic Novel HB Dark Tower: Battle of Jericho Hill: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 2, 3, 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – The Journey Begins: Comics 2 - 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – -

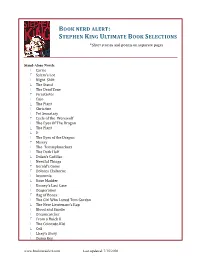

Stephen-King-Book-List

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Later Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands Wizard and Glass www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Wolves and the Calla Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End of Watch Short -

Pennywise Dreadful the Journal of Stephen King Studies

1 Pennywise Dreadful The Journal of Stephen King Studies ————————————————————————————————— Issue 1/1 November 2017 2 Editors Alan Gregory Dawn Stobbart Digital Production Editor Rachel Fox Advisory Board Xavier Aldana Reyes Linda Badley Brian Baker Simon Brown Steven Bruhm Regina Hansen Gary Hoppenstand Tony Magistrale Simon Marsden Patrick McAleer Bernice M. Murphy Philip L. Simpson Website: https://pennywisedreadful.wordpress.com/ Twitter: @pennywisedread Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pennywisedread/ 3 Contents Foreword …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 2 “Stephen King and the Illusion of Childhood,” Lauren Christie …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 3 “‘Go then, there are other worlds than these’: A Text-World-Theory Exploration of Intertextuality in Stephen King’s Dark Tower Series,” Lizzie Stewart-Shaw …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 16 “Claustrophobic Hotel Rooms and Intermedial Horror in 1408,” Michail Markodimitrakis …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 31 “Adapting Stephen King: Text, Context and the Case of Cell (2016),” Simon Brown …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 42 Review: “Laura Mee. Devil’s Advocates: The Shining. Leighton Buzzard: Auteur, 2017,” Jill Goad …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 58 Review: “Maura Grady & Tony Magistrale. The Shawshank Experience: Tracking the History of the World's Favourite Movie. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016,” Dawn Stobbart …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 59 Review: “The Dark Tower, Dir. Nikolaj Arcel. Columbia Pictures, -

THE BALLAD of the SAD CAFÉ Carson Mccullers

THE BALLAD OF THE SAD CAFÉ Carson McCullers Gothic Digital Series @ UFSC FREE FOR EDUCATION The Ballad of the Sad Café (Harper’s Bazaar, 1943) THE town itself is dreary; not much is there except the cotton mill, the two-room houses where the workers live, a few peach trees, a church with two colored windows, and a miserable main street only a hundred yards long. On Saturdays the tenants from the near-by farms come in for a day of talk and trade. Otherwise the town is lonesome, sad, and like a place that is far off and estranged from all other places in the world. The nearest train stop is Society City, and the Greyhound and White Bus Lines use the Forks Falls Road which is three miles away. The winters here are short and raw, the summers white with glare and fiery hot. If you walk along the main street on an August afternoon there is nothing whatsoever to do. The largest building, in the very center of the town, is boarded up completely and leans so far to the right that it seems bound to collapse at any minute. The house is very old. There is about it a curious, cracked look that is very puzzling until you suddenly realize that at one time, and long ago, the right side of the front porch had been painted, and part of the wall — but the painting was left unfinished and one portion of the house is darker and dingier than the other. The building looks completely deserted. -

Talking Book Topics March-April 2016

Talking Book Topics March–April 2016 Volume 82, Number 2 About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics is published bimonthly in audio, large-print, and online formats and distributed at no cost to participants in the Library of Congress reading program for people who are blind or have a physical disability. An abridged version is distributed in braille. This periodical lists digital talking books and magazines available through a network of cooperating libraries and carries news of developments and activities in services to people who are blind, visually impaired, or cannot read standard print material because of an organic physical disability. The annotated list in this issue is limited to titles recently added to the national collection, which contains thousands of fiction and nonfiction titles, including bestsellers, classics, biographies, romance novels, mysteries, and how-to guides. Some books in Spanish are also available. To explore the wide range of books in the national collection, visit the NLS Union Catalog online at www.loc.gov/nls or contact your local cooperating library. Talking Book Topics is also available in large print from your local cooperating library and in downloadable audio files on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site at https://nlsbard.loc.gov. An abridged version is available to subscribers of Braille Book Review. Library of Congress, Washington 2016 Catalog Card Number 60-46157 ISSN 0039-9183 About BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download. To use BARD, contact your cooperating library or visit https://nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. -

STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short Stories and Poems on Separate Pages

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands Wizard and Glass Wolves and the Calla www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End of Watch Short Story -

On Writing : a Memoir of the Craft / by Stephen King

l l SCRIBNER 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Visit us on the World Wide Web http://www.SimonSays.com Copyright © 2000 by Stephen King All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. SCRIBNER and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work. DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING Set in Garamond No. 3 Library of Congress Publication data is available King, Stephen, 1947– On writing : a memoir of the craft / by Stephen King. p. cm. 1. King, Stephen, 1947– 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography. 3. King, Stephen, 1947—Authorship. 4. Horror tales—Authorship. 5. Authorship. I. Title. PS3561.I483 Z475 2000 813'.54—dc21 00-030105 [B] ISBN 0-7432-1153-7 Author’s Note Unless otherwise attributed, all prose examples, both good and evil, were composed by the author. Permissions There Is a Mountain words and music by Donovan Leitch. Copyright © 1967 by Donovan (Music) Ltd. Administered by Peer International Corporation. Copyright renewed. International copyright secured. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Granpa Was a Carpenter by John Prine © Walden Music, Inc. (ASCAP). All rights administered by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc., Miami, FL 33014. Honesty’s the best policy. —Miguel de Cervantes Liars prosper. —Anonymous First Foreword In the early nineties (it might have been 1992, but it’s hard to remember when you’re having a good time) I joined a rock- and-roll band composed mostly of writers. -

Mcginnis Thesis Final

This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of English __________________________ Dr. Eric LeMay Professor, English Thesis Adviser ___________________________ Dr. Mary Kate Hurley Director of Studies, English ___________________________ Dr. Donal Skinner Dean, Honors Tutorial College ECOFICTION: REALIZING THE FULL POTENTIAL OF THE GENRE THROUGH SPECULATIVE AND ECOFEMINIST THEORY and TRICOLORED WATERS: A NOVEL - PART 1 ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University _______________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English ______________________________________ by Kayla McGinnis April 2021 McGinnis 1 Critical Introduction “Warning! Pollutants rife in the air, in the city: carbon emission, racism, oil spills, sexism, deforestation, misogynism, xenophobia, murder . .” (Tsamaase, 5). Ecofiction texts have the power to creatively address how environmental deterioration affects a person depending on their subject position. While many ecofiction works draw from realism, I was attracted to author Tlotlo Tsamaase and her more speculative twists on ecofiction. In her novella, Eclipse our Sins, Tlotlo Tsamaase creates a world in which the earth punishes humanity for the damage it has caused to her. Due to the goddess Mama Earth, humans are punished any time they commit sin against the Earth or one another. Words of hate manifest into a vapor that pollutes the lungs of everyone around them. Humans could resolve this issue by addressing issues of equality and the environment. The upper-class instead focus on making their living situations more comfortable and long-lasting. The upper-class extract energy, female eggs, and bodies from the lower-class in order to make themselves new bodies. -

![<Abby Her> 6 Hehe [00:00] <Kuv Tsis Yog Hmoob](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0068/abby-her-6-hehe-00-00-kuv-tsis-yog-hmoob-7120068.webp)

<Abby Her> 6 Hehe [00:00] <Kuv Tsis Yog Hmoob

Session Start: Fri Aug 26 00:00:05 2005 Session Ident: #hmongtalk [00:00] <aBBy_hER> 6 hehe [00:00] <Kuv_Tsis_Yog_Hmoob> what are u silly hmong ppl saying [00:00] <FakeSmyLe[`phone]> lol [00:00] <+thirtyrOldVIRGIN> sup bananaguy. long time no see baby [00:00] <Guest78841> fake smyle call me [00:00] <FakeSmyLe[`phone]> Who are you guest? [00:00] <BananaGuy21> 4hi DJ miya [00:00] <Guest78841> thirty year old virgin< who are yoU? [00:00] <Got_Abz> 12 who are you ppl?? [00:00] * PnK_RoeX hi.. [00:00] <Nraug_ZooLus> nkaujxwb,,,zoo siab tau paub koj os [00:00] <Guest78841> who are you fakesmile? [00:00] <+thirtyrOldVIRGIN> kuv tsis yog hmoob, we silly hmong say... koj ruam l i tus pig [00:00] <+thirtyrOldVIRGIN> :D [00:00] * FakeSmyLe[`phone] is Kevin's stalker. [00:00] <aBBy_hER> 6 hi bananabuy21 [00:00] <+thirtyrOldVIRGIN> kekekeke [00:00] <AznGuy> Hi pink [00:00] <Guest78841> pig? [00:00] <Got_Abz> 12 i'm sure, smyle.. [00:00] <BananaGuy21> 4hi abby her [00:00] * PnK_RoeX hi [00:00] <nkaujhmoob_sexxy715> ANY GUYS OVER 24 FROM MN WANNA CHAT AND MATURE [00:00] * @Marushi mp3 play : Freebase Freestyle Party.mp3 .::[192kbps 3m22s]::. 1 00 Percent Freestyle Vol.5 2004 [00:00] <FakeSmyLe[`phone]> Yes I am. :D [00:00] * FakeSmyLe[`phone] is Mee. [00:00] <Guest78841> sup pink rolex! [00:00] <Guest78841> been TOO Long since you been here! [00:00] <Kuv_Tsis_Yog_Hmoob> what the hell?????????/ i dont understand [00:01] * Joins: Guest91184 (java@=Vjoep1100688627.dsl.scrm01.pacbell.net) [00:01] * PnK_RoeX hi.. [00:01] <Sithspawn> nkaujhmoob sexy715..WHY..r u ..over 24..and MATURE? [00:01] <Sithspawn> nkaujhmoob sexy715..WHY..r u ..over 24..and MATURE? [00:01] <Guest78841> pink rolex, are you pahoua? [00:01] <Guest78841> or did i mix up [00:01] * PnK_RoeX nope...why? [00:01] <AznGuy> Pink Rolex is hot [00:01] <nkaujhmoob_sexxy715> yes [00:01] <@Marushi> freeestyle [00:01] <+thirtyrOldVIRGIN> yog koj tsis understand. -

Stephen-King-Book-List

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Later Billy Summers Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Wizard and Glass Wolves and the Calla Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End -

Stephen.King Tutto È Fatidico

www.scritturacreativa.org STEPHEN KING TUTTO È FATIDICO (Everything's Eventual, 2002) I racconti contenuti in questo libro sono già stati pubblicati, alcuni in forma diversa: «Autopsy Room Four» inPsychos a cura di Robert Bloch; «The Man in the Black Suit» suThe New Yorker e su Year's Best Fantasy & Horror 1995; «All That You Love Will Be Carried Away» e «The Death of Jack Hamilton» suThe New Yorker, «In the Deathroom» inBlood and Smoke (audio book); «The Little Sisters of Eluria» inLegends; «Everything's Eventual» suFantasy & Science Fiction e inFI3 (CD-ROM); «L.T.'s Theory of Pets» suThe Best of the Best 1998; «The Road Virus Heads North» in 999; «Lunch at the Gotham Café» inDark Love, inYears's Best Fantasy and Horror 1996 e in Blood and Smoke (audio book); «That Feeling, You Can Only Say What It Is in French» suThe New Yorker, «1408» inBlood and Smoke (audio book); «Riding the Bullet» usci-to come e-book per la Scribner e «Luckey Quarter» suUSA Weekend. Questo libro èdedicato a Shane Leonard Indice «Ho preso da un mazzo tutte le carte di picche e un Jolly. Le picche, dall'asso al Re, equivalevano ai numeri dall'uno al tredici. Il Jolly al quattordici. Le ho mischiate e le ho disposte sul tavolo. L'ordine in cui sono uscite è diventato quello dei racconti, numera-ti in base all'elenco che mi aveva mandato la casa editrìce. Ne è ri-sultato un equilibrio davvero efficace tra i racconti più ricercati e quelli a effetto. Ho anche aggiunto un breve commento prima o dopo ogni racconto, a seconda della posizione che mi sembrava più adatta.