Royal Cabinets of Physics in Portugal and Brazil: an Exploratory Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ATINER's Conference Paper Proceedings Series ARC2017

ATINER CONFERENCE PRESENTATION SERIES No: ARC2017-0106 ATINER’s Conference Paper Proceedings Series ARC2017-0106 Athens, 28 September 2018 Scenographic Interventions in Portuguese Romantic Architecture Luís Manuel Lourenço Sêrro Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10683 Athens, Greece ATINER’s conference paper proceedings series are circulated to promote dialogue among academic scholars. All papers of this series have been blind reviewed and accepted for presentation at one of ATINER’s annual conferences according to its acceptance policies (http://www.atiner.gr/acceptance). © All rights reserved by authors. 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PRESENTATION SERIES No: ARC2017-0106 ATINER’s Conference Paper Proceedings Series ARC2017-0106 Athens, 28 September 2018 ISSN: 2529-167X Luís Manuel Lourenço Sêrro, Associate Professor, Lusíada University, Portugal. Scenographic Interventions in Portuguese Romantic Architecture ABSTRACT When Kant established the noumenon1 as the limit of knowledge in his Critique of Judgment, he set off a reaction among the most distinguished philosophers of the infinite: Fischte, Schilling, and Hegel. This consciousness of the infinite and its analysis through the feeling of the sublime was the basis of all European Romanticism, as well as of the artistic currents that flowed from it. Although the theme of the sublime has been studied since Longinus, it was Hegel who extended the concept through the analysis of space and time in his The Philosophy of Nature, because nature as de-termination2 of the idea necessarily falls in space and time.3 Consequently, the artistic achievement of that era could only be a figurative representation of the sublime and the integration of all arts in a whole with the purpose of awakening the feeling of Gesamtkunstwerk. -

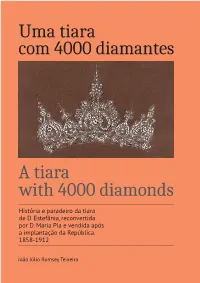

Uma Tiara Com 4000 Diamantes

Uma tiara com 4000 diamantes A tiara with 4000 diamonds História e paradeiro da tiara de D. Estefânia, reconvertida por D. Maria Pia e vendida após a implantação da República. 1858-1912 João Júlio Rumsey Teixeira João Júlio Rumsey Teixeira Uma tiara com 4000 diamantes História e paradeiro da tiara de D. Estefânia, reconvertida por D. Maria Pia e vendida após a implantação da República. 1858-1912 João Júlio Rumsey Teixeira Uma tiara com 4000 diamantes João Júlio Rumsey Teixeira Título: Uma tiara com 4000 diamantes. História e paradeiro da tiara de D. Estefânia, reconvertida por D. Maria Pia e vendida após a implantação da República. 1858-1912 Aos meus pais, por me ensinarem a ver. Autor: João Júlio Rumsey Teixeira [email protected] Prefácio: Teresa Maranhas, PNA, DGPC Revisão: Teresa Maranhas, PNA, DGPC Hugo Xavier, PNP, PSML Capa, design e paginação: Nicolás Fabian nfabian.pt Imagem da capa: Desenho do diadema de D. Estefânia, Nicolás Fabian, técnica mista sobre papel, col. autor. Tradução: Autor Revisão da tradução: Catarina Alcântara Luz Abril 2020, Todos os direitos reservados Uma tiara com 4000 diamantes João Júlio Rumsey Teixeira Índice 7 9 15 Prefácio Introdução Identificação e Análise Pericial 21 37 39 História, Conclusão Apêndice Proveniência Documental e Autorias Abreviaturas ANTT - Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo APNA - Arquivo do Palácio Nacional da Ajuda Col. - Coleção 55 57 58 Cx. - Caixa DGFP - Direção Geral da Fazenda Pública Preface Introduction Identification Doc. - Documento and expert Doc. cit. - Documento citado analysis ELI - Espólio Leitão & Irmão FCG - Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian Fig. - Figura 60 67 68 Inv. -

Download Catalogue

SCALA 2019 1 EXHIBITION BOOKS THE FRICK COLLECTION Welcome to Scala’s 2019 catalogue! We continue our mission to Moroni: The Riches of showcase the world’s leading arts and heritage collections in order Renaissance Portraiture to widen cultural knowledge and appreciation. This year we welcome £50 / $65 Publication: February new partners in the UK, US, Middle East, Russia, Eastern Europe, 244 pages; hb Ireland and Canada, while continuing to produce publications for 280 x 240 mm (9½ x 11 in.) 978 1 78551 184 4 (hb) our esteemed long-term partners. Aimee Ng is Associate Curator at The Frick Collection, New York. Among our highlights for 2019 are a luxurious companion to the Simone Facchinetti is Curator at Roman Art collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museo Adriano Bernareggi, Bergamo. Arturo Galansino is Director accompanying books for two new galleries at the Science Museum, of Palazzo Strozzi, Florence. London. More major institutions worldwide have joined our Director’s Accompanies a major exhibition at Choice series, including the Hermitage and the Fabergé Museum. The Frick Collection from 21 February We are very proud to present our latest children’s title in association to 2 June 2019 with Windsor Castle and we have two more major institutions joining our Schools and Colleges list. Our publications for the performing arts this year encompass the Royal Albert Hall, Royal Academy of Dance and St Cecilia’s Hall in Edinburgh. Our reputation continues to be one of the highest quality – both in terms of the beautiful books we produce and the expert service we provide – and we remain extremely proud of our association with some of the best cultural institutions in the world. -

Presentation

StartStart TourTour End Travel School The National Palace of Ajuda The National Palace of Ajuda, or Palace of Our Lady of Ajuda, is a Portuguese national monument in the district of Ajuda, in Lisbon. The Old Royal Palace was, originally, King John V’s holiday house. Now it is a large, magnificent museum. Back to Map Forest Park of Monsanto The Forest Park of Monsanto is a very attractive place in terms of fauna and flora. It is a forest area on the outskirts of Lisbon with some clearings and areas with a wide view over the city and the river. The Park also has several recreational areas, with Back to Map different sports and activities we can j AprilApril 25th25th BridgeBridge The April 25th Bridge (named after our Revolution but formerly the Salazar Bridge ) was commissioned by Salazar, our former dictator in the 60s. This bridge links Lisbon to the city of Almada, Back to Map across the Tagus river. TheThe PalacePalace ofof BelBeléémm The National Palace of Belém is the official residence of the president of Portugal, Aníbal Cavaco Silva. It is located in the district of Belém, Lisbon, close to the Tagus river and near many touristic and cultural attractions. Back to Map BotanicBotanic TropicalTropical GardenGarden The Botanic Tropical Garden was created in January 1906, and it is located in Bel ém, Lisbon, near the Hieronymites Monastery. Spread over 7 ha, it includes a botanical garden with (some rare) tropical Back to Map specimens from the former colonies, and a greenhouse with heatin g. The Hieronymites Monastery The Hieronymites Monastery is located in the district of Belém. -

Sources for the History of Art Museums in Portugal» Final Report

PROJETHA Projects of the Institute of Art History Sources for the History of Art Museums in Portugal [PTDC/EAT-MUS/101463/2008 ] Final Report PROJETHA_Projects of the Institute of Art History [online publication] N.º 1 | «Sources for the History of Art Museums in Portugal» _ Final Report Editorial Coordination | Raquel Henriques da Silva, Joana Baião, Leonor Oliveira Translation | Isabel Brison Institut of Art History – Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa | 2013 PROJETHA_ Projects of the Institute of Art History SOURCES FOR THE HISTORY OF ART MUSEUMS IN PORTUGAL CONTENTS Mentioned institutions - proposed translations _5 PRESENTATION | Raquel Henriques da Silva _8 I. PARTNERSHIPS The partners: statements Instituto dos Museus e da Conservação | João Brigola _13 Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga | António Filipe Pimentel _14 Art Library of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation | Ana Paula Gordo _15 II . THE TASKS TASK 1. The origins of the Galeria Nacional de Pintura The origins of the Galeria Nacional de Pintura | Hugo Xavier _17 TASK 2. MNAA’s historical archives database, 1870-1962 The project “Sources…” at the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga | Celina Bastos e Luís Montalvão _24 Report of the work undertaken at the Archive of the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. Research Fellowship | Andreia Novo e Ema Ramalheira _27 TASK 3. Exhibitions in the photographic collection of MNAA . The Photographic Archive at the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. A historical sketch | Hugo d’Araújo _35 TASK 4. Inventory and study of the “Arrolamentos” of the Royal Palaces of Necessidades and Ajuda. The project “Sources…” at the Palácio Nacional da Ajuda | PNA _52 Report of the work undertaken at the Palácio Nacional da Ajuda. -

Portugal 60-Card Set ANTIQUE STEREOVIEWS of PORTUGAL

(1 / 21) Foreign Views – Underwood & Underwood: Portugal 60-card set 1 - The Castle of St. George and city from the Tagus - Lisbon, Portugal - S693, 2305 2 - Commerce Square, Joseph I. Statue, Augusta Arch, and Government buildings - Lisbon, Portugal - 3 - Statue of Joseph I. And Augusta Arch, Praça do Comercio, Lisbon, Portugal - 2307 ANTIQUE STEREOVIEWS OF PORTUGAL Copyright © 2003 J. M. Martins Ferreira. All Rights Reserved. (2 / 21) Foreign Views – Underwood & Underwood: Portugal 60-card set 4 - The Royal Barge at Lisbon, Portugal, conveying the King and Queen to the Carlos I. - bound for the Azores - 5 - The Fish Girls of Lisbon, Portugal - 6 - Praça (Square) and Column of Dom Pedro IV. - north to Theater of Dona Maria II. - Lisbon, Portugal - R5 ANTIQUE STEREOVIEWS OF PORTUGAL Copyright © 2003 J. M. Martins Ferreira. All Rights Reserved. (3 / 21) Foreign Views – Underwood & Underwood: Portugal 60-card set 7 - A quaint street in the old quarter of Lisbon, Portugal - 8 - St. George Castle and the Tagus (S.W.) from Nossa Senhora do Monte (Our Lady of the Mountain), Lisbon, Portugal. - 9 - Grand Salon of the Royal Palace of Ajuda, residence to the Queen-Dowager Maria Pia, Lisbon, Portugal - ANTIQUE STEREOVIEWS OF PORTUGAL Copyright © 2003 J. M. Martins Ferreira. All Rights Reserved. (4 / 21) Foreign Views – Underwood & Underwood: Portugal 60-card set 10 - Pantheon of the Kings and Queens, St. Vincent Monastery - highest in center, Luis I., father of the present King - Lisbon, Portugal. - 11 - Where the old Aqueduct (1729-49) crosses the Alcantara Valley - highest arch 204 feet - Lisbon, Portugal - ANTIQUE STEREOVIEWS OF PORTUGAL Copyright © 2003 J. -

Sonia Falcone Successfully Intervenes the Royal Palace in Lisbon

PRESS RELEASE Sonia Falcone successfully intervenes the Royal Palace in Lisbon The iconic work Color Fields in the entrance to the National Palace of Ajuda in Lisbon, Portugal. From left to right: Mrs. Hernández, Prince Charles Philipe de Orleans, Sonia Falcone and Duchess Diana de Cadaval. The official inauguration of Sonia Falcone´s artistic intervention: Life Fields National Palace of Ajuda in Lisbon on September 15, 2017 was unanimously praised by hundreds of attendees. After the opening speeches, the Portuguese Minister of Culture, Luís Filipe de Castro Mendes, led a guided tour. At the end of the tour Castro Mendes praised the quality of this project that displays 50 different pieces in 29 rooms of the Royal Palace, some of which were especially created for this occa- sion in order to establish a dialogue with the spaces inside this historical site. Minister Castro Mendes congratulated the director of the Palace, José Alberto Ribeiro, for the election and coordination of this enormous artis- tic exhibition, while expressing his admiration for the body of the work of this Bolivian artist who exhibits in Portugal for the first time. “I want to highlight both the value of the art of Sonia Falcone and the success of the curatorship that has created a truly amazing dialogue with each of the spaces of the Palace,” Castro Mendes said in his opening address. For his part, director Ribeiro thanked the Minister for his presence, the collaboration of Paula Araújo da Silva, Director General of Cultural Her- itage of Portugal, and Prince Charles Philipe and Diana of Orleans, who from the beginning of the project were key figures in fulfilling this -ex hibition that brings to Portugal an important part of the body of work Perrine Falcone, daughter of the artist, next to Eternal Love. -

A Seven-Day Getaway to Portugal

W&L Traveller Presents: A Seven-Day Getaway to Portugal A Seven-Day Getaway to Portugal (March 18-25, 2019) Portugal’s remoteness from the capitals of Europe and its close relationship to the sea have contributed to her unique cultural traditions. Visitors will discover a land blessed www.Keytours.com with a lush fertile countryside, antique villages, fairy-tale castles, fine wine, magnificent palaces, elegant gardens-qualities that have helped to make Portugal Travel and Leisure’s destination of the year for 2017. Yet, despite these distinctions, Portugal remains one of Duration: 8 Days* the least-known nations in Europe. Through such great explorers as Prince Henry the Activity Level: Moderate Navigator and Vasco de Gama, Portugal inspired and led the European discovery of the world. Her Golden Age lasted well over 100 years. But then, like a Sleeping Beauty, she Cost: $3,495 receded from the world stage, enclosed and apart. Single Supplement: $795 In this generous two-city getaway, we’ll explore her rich history and her surprisingly Deposit: $500 vibrant contemporary life. Our journey begins with the cultural wealth of Lisbon. Our panoramic tour will discover many broad boulevards, parks, and cultural monuments, Operator: Keytours Vacations including the Jeronimos Monastery, that befit one of the great world capitals. The beauti- *7 days - excluding overnight flight per itinerary day 1 ful palaces of Sintra and Ajuda are also jewels in Portugal’s crown. During our stay in Lis- bon, we’ll enjoy dinner in one of the city’s Fado houses, where we’ll discover Portugal’s soul revealed in her music. -

Discovering Lisbon

Discovering Lisbon ABOUT Photo: Turismo de Portugal Discovering Lisbon Lisbon is a city that makes you want to go exploring, to discover whatever might appear in every neighbourhood, on every street. It’s a safe and friendly city, relatively small but with so much to see. It’s an ideal place to spend a few days or as a starting point for touring the country. It’s old. It’s modern. It is, without doubt, always surprising. You can choose a topic or a theme to explore it. The range is wide: Roman Lisbon, Manueline, Baroque or Romantic Lisbon, literary Lisbon, the Lisbon of Bohemian nightlife, the city of Fado. And there are also very different ways of exploring: by foot, by tram, by segway, by hop-on-hop-off bus, in a tuk tuk, seen from the river on a boat trip or from the other side, after crossing the Tagus on a cacilheiro ferry... the suggestions are endless. However, there are some essential sites that simply cannot be missed, and are always on the list. Like the historic Alfama and Castelo districts, with one of the most fabulous views over the city and the river. You must go from downtown towards Belém, the neighbourhood of the Discoveries, with the Belém Tower and the Jerónimos Monastery, both World Heritage. But also with the original Coach Museum and the modern Belém Cultural Centre. Oh, and don’t forget to taste the delicious pastéis de nata (custard tarts)! Leave Chiado and Bairro Alto for the late afternoon and the evening. These are guaranteed nightlife spots, as is Cais do Sodré, nearer the river. -

Maria João Burnay Murano Glass at National Palace of Ajuda The

Maria João Burnay MURANO GLASS AT NATIONAL PALACE OF AJUDA The political turmoil experienced during the second half of the 19th century caused great transformations in Venice. Following the fall of the Republic in 1797 and the foreign invasions that relied and ended the Austrian ruling, Venice joined the Italian kingdom in 1866, the year in wich it was observed a clear rebirth of the economical activities, namely the glass industry that was affected by the competitive Bohemian and Austrian (glass industry) which was stimulated during the Habsburgs period. In this political and economic context a few years before in 1862, the princess of Savoy Maria Pia (1847-1911) daughter of King Vitor Emanuel of Italy married with King D. Louis I of Portugal (1838-1889) and moved to the Palace of Ajuda, one of the royal residences until 1910, the year of the proclamation of the Portuguese Republic. Ajuda became the official royal residence of the Portuguese monarchs and Queen Maria Pia made the renovation of interiors following the fashion of the day. Balls and several ceremonies were held in the palace rooms which became the center of the Portuguese Court in the 19th century. The palace was closed after the proclamation of the Republic in 1910 and reopened to the public in 1968 as a museum gathering important collections from the 15th to the 20th century, mainly of decorative arts. Glass collection plays a significant role with about 12.500 objects from the leading European manufacturers. Murano glass collection amounts 592 objects1 of utilitarian 1 It can be found on Palácio Nacional da Ajuda Database: http://www.matriznet. -

The Colonial Architecture of Minas Gerais in Brazil*

THE COLONIAL ARCHITECTURE OF MINAS GERAIS IN BRAZIL* By ROBERT C. SMITH, JR. F ALL the former European colonies in the New World it was Brazil that most faithfully and consistently reflected and preserved the architecture of the mother-country. In Brazil were never felt those strange indigenous influences which in Mexico and Peru produced buildings richer and more complicated in design than the very models of the peninsular Baroque.' Brazil never knew the exi gencies of a new and severe climate necessitating modifications of the old national archi tectural forms, as in the French and English colonies of North America, where also the early mingling of nationalities produced a greater variety of types of construction. And the proof of this lies in the constant imitation in Brazil of the successive styles of architecture in vogue at Lisbon and throughout Portugal during the colonial period.2 From the first establish- ments at Iguarassi3 and Sao Vicente4 down to the last constructions in Minas Gerais, the various buildings of the best preserved colonial sites in Brazil-at Sao Luiz do Maranhao,5 in the old Bahia,6 and the earliest Mineiro7 towns-are completely Portuguese. Whoever would study them must remember the Lusitanian monuments of the period, treating Brazil * The findings here published are the result in part of guesa), circa 1527. researches conducted in Brazil in 1937 under the auspices 2. The Brazilian colonial period extends from the year of the American Council of Learned Societies. of the discovery, 1500, until the establishment of the first i. In Brazil I know of only two religious monuments Brazilian empire in 1822. -

Best Historic Locations in Lisbon"

"Best Historic Locations in Lisbon" Realizado por : Cityseeker 8 Ubicaciones indicadas Baixa "An Architectural Marvel" No trip to Lisbon is complete without a visit to Baixa, one of the centrally located districts of the city. Although the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake inflicted a lot of damage on the area, subsequent renovations have ensured that it is still one of the most impressive districts of Lisbon. Baixa is synonymous with Neoclassical buildings and grand squares, and is a delight to explore by @ravi on foot. While you walk around admiring the architecture, you will come across a vast assortment of shops, among which you will also find numerous traditional traders. Rua Augusta, Rua da Prata and Rua da Aurea are the three main shopping streets where you can find a little bit of everything, but which are known particularly for jewelry stores. +351 21 031 2810 (Tourist Information) [email protected] Rua Augusta, Lisboa Chiado "A Lisbon Icon" The 16th-century Portuguese poet, António Ribeiro was fondly known as 'Chiado', and it is from this source that one of Lisbon's most iconic districts takes its name. Easily identified by the statue of António Ribeiro that stands at the center of the square, Chiado is a must-visit on a trip to Lisbon. The area has retained its historic charm, and establishments like by Scalleja [2] Restaurante Tavares have been in existence from the 18th Century. Although a fire raged through the district in 1988, it hasn't lost any of its appeal, and still remains one of the most popular shopping districts in the city.