Chapter 3 Prehistory of Fiji and Indigenous Narratives of Fijian Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

Introduction Brij V. Lal Soldiers rioting on the steps of parliament house in Papua New Guinea; tumultuous politics besetting the presidency in Vanuatu; political assassi nations in New Caledonia; confrontation between soldiers and civilians on the troubled island of Bougainville. In other, calmer times, such inci dents of terror and violence would have stunned observers of Pacific Island affairs. But in the aftermath of the dramatic events in Fiji, news of upheaval in the islands is increasingly being greeted with a weary sense of deja vu. Such has been their impact that the Fiji coups and the forces they have unleashed are already being seen as marking, for better or worse, a turning point not only in the history ofthat troubled island nation but also in the contemporary politics ofthe Pacific Islands region. The issues and emotions that the Fiji coups have engendered touch on some of the most fundamental issues of our time: the tension between the rights ofindigenous peoples ofthe Pacific Islands and the rights ofthose of more recent immigrant or mixed origins; the role and place of traditional customs and institutions in the fiercely competitive modern political arena; the structure and function of Western-style democratic political processes in ethnically divided or nonegalitarian societies; the use of mili tary force to overthrow ideologically unacceptable but constitutionally elected governments. These and similar issues, rekindled by the events in Fiji, will be with us for a long time to come. Unlike any other event in recent Pacific Islands history, the Fiji crisis has generated an unprecedented outpouring of popular and scholarly litera ture, as our Book Review and Resources sections amply demonstrate. -

Kilaka Forest

Kilaka Forest Conservation Area Management Plan Copyright: © 2016 Wildlife Conservation Society Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided that the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited withoutprior written consent of the copyright owner. Citation: WCS (2016) Kilaka Forest Conservation Area Management Plan. Wildlife Conservation Society, Suva, Fiji. 34 pp. Photograph (front cover): ©Ruci Lumelume/WCS Graphic design & Layout: cChange NOTE: This management plan may be amended from time to time. To obtain a copy of the current management plan, please contact: Wildlife Conservation Society Fiji Country Program 11 Ma’afu Street Suva Republic of Fiji Islands Telephone: +679 331 5174 Email: [email protected] Kilaka Forest Conservation Area Management Committee Kilaka Village Kubulau District Bua Province Republic of Fiji Kubulau Resource Management Committee Kubulau District Bua Province Republic of Fiji ENDORSEMENT On this day, 24 November, 2016 at Kilaka Village in the district of Kubulau, Bua Province, Vanua Levu in the Republic of Fiji Islands, we the undersigned endorse this management plan and its implementation. We urge the people of all communities in Kubulau and key stakeholders from government, private and non-government sectors to observe the plan and make every effort to ensure effective implementation. Minister, Ministry of Forests Tui -

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Reef Check Description of the 2000 Mass Coral Beaching Event in Fiji with Reference to the South Pacific

REEF CHECK DESCRIPTION OF THE 2000 MASS CORAL BEACHING EVENT IN FIJI WITH REFERENCE TO THE SOUTH PACIFIC Edward R. Lovell Biological Consultants, Fiji March, 2000 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................4 2.0 Methods.........................................................................................................................................4 3.0 The Bleaching Event .....................................................................................................................5 3.1 Background ................................................................................................................................5 3.2 South Pacific Context................................................................................................................6 3.2.1 Degree Heating Weeks.......................................................................................................6 3.3 Assessment ..............................................................................................................................11 3.4 Aerial flight .............................................................................................................................11 4.0 Survey Sites.................................................................................................................................13 4.1 Northern Vanua Levu Survey..................................................................................................13 -

The Case of Fiji

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 25 Issues 3&4 1992 Democracy and Respect for Difference: The Case of Fiji Joseph H. Carens University of Toronto Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Cultural Heritage Law Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph H. Carens, Democracy and Respect for Difference: The Case of Fiji, 25 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 547 (1992). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol25/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY AND RESPECT FOR DIFFERENCE: THE CASE OF FIJI Joseph H. Carens* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................. 549 I. A Short History of Fiji ................. .... 554 A. Native Fijians and the Colonial Regime .... 554 B. Fijian Indians .................. ....... 560 C. Group Relations ................ ....... 563 D. Colonial Politics ....................... 564 E. Transition to Independence ........ ....... 567 F. The 1970 Constitution ........... ....... 568 G. The 1987 Election and the Coup .... ....... 572 II. The Morality of Cultural Preservation: The Lessons of Fiji ................. ....... 574 III. Who Is Entitled to Equal Citizenship? ... ....... 577 A. The Citizenship of the Fijian Indians ....... 577 B. Moral Limits to Historical Appeals: The Deed of Cession ............. ....... 580 * Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Toronto. -

Report SCEFI Evaluation Final W.Koekebakker.Pdf

Strengthening Citizen Engagement in Fiji Initiative (SCEFI) Final Evaluation Report Welmoed E. Koekebakker November, 2016 ATLAS project ID: 00093651 EU Contribution Agreement: FED/2013/315-685 Strengthening Citizen Engagement in Fiji Initiative (SCEFI) Final Evaluation Report Welmoed Koekebakker Contents List of acronyms and local terms iv Executive Summary v 1. Introduction 1 Purpose of the evaluation 1 Key findings of the evaluation are: 2 2. Strengthening Citizen Engagement in Fiji Initiative (SCEFI) 3 Intervention logic 4 Grants and Dialogue: interrelated components 5 Implementation modalities 6 Management arrangements and project monitoring 6 3. Evaluation Methodology 7 Evaluation Questions 9 4. SCEFI Achievements and Contribution to Outcome 10 A. Support to 44 Fijian CSOs: achievements, assessment 10 Quantitative and qualitative assessment of the SCEFI CSO grants 10 Meta-assessment 12 4 Examples of Outcome 12 Viseisei Sai Health Centre (VSHC): Empowerment of Single Teenage Mothers 12 Youth Champs for Mental Health (YC4MH): Youth empowerment 13 Pacific Centre for Peacebuilding (PCP) - Post Cyclone support Taveuni 14 Fiji’s Disabled Peoples Federation (FDPF). 16 B. Leadership Dialogue and CSO dialogue with high level stakeholders 16 1. CSO Coalition building and CSO-Government relation building 17 Sustainable Development Goals 17 Strengthening CSO Coalitions in Fiji 17 Support to National Youth Council of Fiji (NYCF) and youth visioning workshop 17 Civil Society - Parliament outreach 18 Youth Advocacy workshop 18 2. Peace and social cohesion support 19 Rotuma: Leadership Training and Dialogue for Chiefs, Community Leaders and Youth 19 Multicultural Youth Dialogues 20 Inter-ethnic dialogue in Rewa 20 Pacific Peace conference 21 3. Post cyclone support 21 Lessons learned on post disaster relief: FRIEND 21 Collaboration SCEFI - Ministry of Youth and Sports: Koro – cash for work 22 Transparency in post disaster relief 22 4. -

EMS Operations Centre

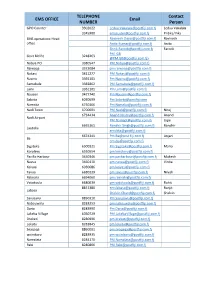

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Proceedings of the Pacific Regional Workshop on Mangrove Wetlands Protection and Sustainable Use

PROCEEDINGS OF THE PACIFIC REGIONAL WORKSHOP ON MANGROVE WETLANDS PROTECTION AND SUSTAINABLE USE THE UNIVERSITY OF THE SOUTH PACIFIC MARINE STUDIES FACILITY, SUVA, FIJI JUNE 12 – 16, 2001 Hosted by SOUTH PACIFIC REGIONAL ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME Funded by CANADA-SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM (C-SPODP II) ORGANISING COMMITTEE South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) Ms Mary Power Ms Helen Ng Lam Institute of Applied Sciences Ms Batiri Thaman Professor William Aalbersberg Editing: Professor William Aalbersberg, Batiri Thaman, Lilian Sauni Compiling: Batiri Thaman, Lilian Sauni ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The organisers of the workshop would like to thank the following people and organisations that contributed to the organising and running of the workshop. § Canada –South Pacific Ocean Deveopment Program (C-SPODP II) for funding the work- shop § South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) for organising the workshop § Institute of Applied Science (IAS) staff for the local organisation of the workshop and use of facilities § The local, regional, and international participants that presented country papers and technical reports § University of the Pacific (USP) dining hall for the catering § USP media centre for assistance with media equipment § Professor Randy Thaman for organising the field trip TABLE OF CONTENTS Organising Committee Acknowledgements Table of Contents Objectives and Expected Outcomes of Workshop Summary Report Technical Reports SESSION I: THE VALUE OF MANGROVE ECOSYSTEMS · The Value of Mangrove Ecosystems: -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Fiji: Severe Tropical Cyclone Winston Situation Report No

Fiji: Severe Tropical Cyclone Winston Situation Report No. 8 (as of 28 February 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Regional Office for the Pacific (ROP) in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 27 to 28 February 2016. The next report will be issued on or around 29 February 2016. Highlights On 20 and 21 February Category 5 Severe Tropical Cyclone Winston cut a path of destruction across Fiji. The cyclone is estimated to be one of the most severe ever to hit the South Pacific. The Fiji Government estimates almost 350,000 people living in the cyclone’s path could have been affected (180,000 men and 170 000 women). 5 6 42 people have been confirmed dead. 4 1,177 schools and early childhood education centres (ECEs) to re-open around Fiji. Winston 12 2 8 Total damage bill estimated at more than FJ$1billion or 10 9 1 almost half a billion USD. 3 11 7 87,000 households targeted for relief in 12 priority areas across Fiji. !^ Suva More than Population Density Government priority areas 51,000 for emergency response 1177 More densely populated 42 people still schools and early are shown above in red Confirmed fatalities sheltering in childhood centres and are numbered in order evacuation centres set to open Less densely populated of priority Sit Rep Sources: Fiji Government, Fiji NEOC/NDMO, PHT Partners, NGO Community, NZ Government. Datasets available in HDX at http://data.hdx.rwlabs.org. Situation Overview Food security is becoming an issue with crops ruined and markets either destroyed or inaccessible in many affected areas because of the cyclone. -

Tikina Nailaga Sustainable Development Plan 2018 - 2038 1

TIKINA NAILAGA SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2018 - 2038 1 NACULA SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PLAN Presented by Tikina Nailaga Development Committee Contributors Apolosa Robaigau, Rusila Savou-Wara, Kesaia Tabunakawai, Alfred Ralifo, Metui Tokece (WWF-Pacific), Tikina Nailaga Community Representatives Layout & Design: Kitione Roko & Kalo Williams Edited by: Vilisite Tamani & Amelia Makutu Finalised: July 2018 Funded by: Supported by: CONTENTS Acknowledgement 010104 Foreword 05 Summary 06 Vision/Mission/Objective 07 List of Thematic Areas 08 Background 09 Socio-Economic Background 10 The Process of Developing the Sustainable District Development Plan 11 Alignment to Fiji’s National Frameworks 12 Governance and Implementation Structure 13 Summary Costs for Thematic Areas 14 Thematic Areas and Activities 15 Annexes 30 Acknowledgement The Nailaga Sustainable Development Plan is the result of an extensive 5-year (2013-2017) consultation and collaboration process with invaluable input from the following donors, partner organisations, government ministries and individuals. The people of the United States of America through USAID and PACAM Programme and the people of Australia through Australian Aid Programme for funding the completion of this Tikina Nailaga District Sustainable Development Plan. The Government of Fiji, through the relevant ministries that contributed to the development of the plan i.e. The Commissioner Western’s Office, District Office Ba, Department of Land Use and Planning, Ba Provincial Office, Ministry of Education. the plan. World Wide Fund for nature Pacific Office, for leading the facilitation process during the development of Mr Jo Vale and Jeremai Tuwai , the two former Mata ni Tikina (District representatives) who played an important role during the community consultation process . The people of Nailaga District for their participation and contribution towards the development of the plan. -

Is Fiji Ready for a Free Press

VOLUME 17. No.1I/MAY, 2012 ISSN 1029-7316 Pageant scrutiny by EDWARD TAVANAVANUA and PARIJATA GURDAYAL scheduled for the panel to view and assess the contestants. Hoerder, who has experience as HE Miss World Fiji 2012 Pageant is under a Miss Hibiscus judge, said the fact that they scrutiny following a plethora of allegations, only had one meeting with the contestants including that the winner was pre-deter- T was extremely irregular. The assessment also mined well before the judging panel deliberated. was confined to their life story or experiences. Although the pageant concluded about two Blake has since confirmed in a press state- weeks ago, the Miss World Organisation has ment that no judging criteria or points system yet to add the winner of the Fiji franchise, was used to judge the contestants. Torika Watters, to the list of winners on its official “If you are asked to be a judge for Miss World, website. The organisation has yet to respond to then you should come with the mindset of hear- queries e-mailed to it last week. Extra ing genuine stories and not with the expecta- Fiji franchise director Andhy Blake refused requests tions of age, point’s tabulation,” he said. yards for an in-person interview. When asked over the phone He added that based on this fact that no judging whether Watters had been accepted into the interna- or points system was employed, any allegations of pay off tional competition, he said “it’s a surprise”. judging being rigged are false. He also declined to comment on whether the funds “I gave my own personal opin- raised from a charity ball, which was held to create ions on whoever I saw fitting for awareness on mental health, had been given to St Giles the title without influencing the Hospital.