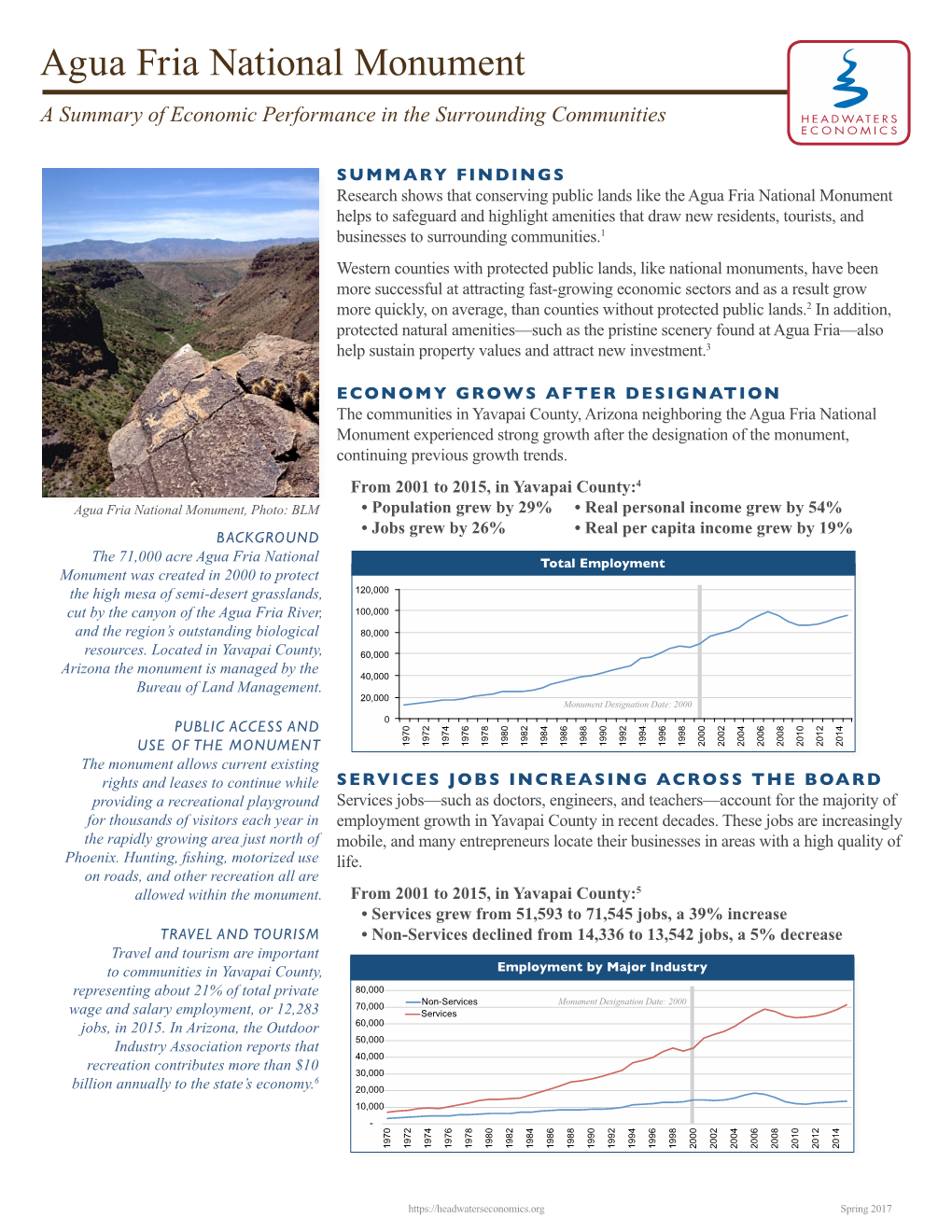

Agua Fria National Monument a Summary of Economic Performance in the Surrounding Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CENTRAL ARIZONA SALINITY STUDY --- PHASE I Technical Appendix C HYDROLOGIC REPORT on the PHOENIX

CENTRAL ARIZONA SALINITY STUDY --- PHASE I Technical Appendix C HYDROLOGIC REPORT ON THE PHOENIX AMA Prepared for: United States Department of Interior Bureau of Reclamation Prepared by: Brown and Caldwell 201 East Washington Street, Suite 500 Phoenix, Arizona 85004 Brown and Caldwell Project No. 23481.001 C-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ 2 LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 4 2.0 PHYSICAL SETTING ....................................................................................................... 5 3.0 GENERALIZED GEOLOGY ............................................................................................ 6 3.1 BEDROCK GEOLOGY ......................................................................................... 6 3.2 BASIN GEOLOGY ................................................................................................ 6 4.0 HYDROGEOLOGIC CONDITIONS ................................................................................ 9 4.1 GROUNDWATER OCCURRENCE .................................................................... -

A Regional Groundwater Flow Model of the Salt River Valley - Phase I

SDMS DOCID#1142207 ARIZONA DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES A REGIONAL GROUNDWATER FLOW MODEL OF THE SALT RIVER VALLEY - PHASE I PBOEN~ AC~ MANAGEMENT AREA HYDROGEOLOGIC FRAMEWORK AND BASIC DATA REPORT BY EDWIN F. CORKHILL, STEVE CORELL, BRADLEY M. HILL. and DAVID A. CARR HYDROLOGY DIVISION MODELING REPORT NO. 6 Phoenix, Arizona April, 1993 ARIZO~A DEPARTMENT OF \'1ATER RESOURCES A REGIONAL GROUND\VATER FLOW MODEL OF THE SALT RIVER VALLEY ~ PHASE I PHOENIX ACTIVE MANAGEMENT AREA HYDROGEOLOGIC FRAMEWORK AND BASIC DATA REPORT Final Report by Edwin Corkhilt Steve CorelL Bradley M. HilL and David A. Modeling Report No. 6 Hydrology Division - Groundwater Modeling April 1, 1 Abstract The Phoenix Active :Management Area groundwater flow model focuses on the hydrologic system of the Salt River Valley, the most intensive water use area of the state. The goal of the hydrologic study and modeling effort was to develop a quantitative tool to test various groundwater management scenarios. The predevelopment hydrologic system (circa 1900) of the Salt River Valley is analyzed. Various components of groundwater inflow and outflov,/ are identified. A predevelopment groundviater budget is presented. The total inflows and outflows were in approximate balance and equaled approximately 139J~OO acre-feet per year. The modern hydrologic system (1978-198:-1) is analyzed. The vari.ous components of groundv,:rner inflow and outflov<' are identified. Detailed descriptions of the methodologies used to analyze the components of flow are provided. A groundwater budget for the period 19/X-1 Y88 is presented. The total inflows were approximately 13.5 million acre-feet and the total outflow-, were approximately 14.0 million acre-feet The estimated decrease in the volume of groundwater in storage \\'US 0.5 rnillion acre-feet Various recommendations are provided to improve future data collection and analysis efforts. -

Arizona Historic Bridge Inventory

STATE OF ARIZONA HISTORIC PROMINVENTORY FORM Granite Creek Bridge mumy YaTapcd inventorynurh OW42 milwst 318.13 invmtory rout. SR 88 A Iocabn 0.3 rnl E Id SR 89 Came imsdMte Creek cityhriciniv Preston USGS quadrangle hot! district 85 Ul'M referem 12.370057.3831113 STRUCTURAL INFORMATION main span number 2 main span type 104 appr, span number 0 appr. vantype degrea of skew 0 guardrail type 6 main span lhgth 43.0 tuperstructve concrete three-beamdeck girder structure length 89.0 sbstrmture concrete abutmenb, wlngwalls and pier roadway width 20.1 floarldeddng concrete deck swumrre width 23.8 othn fuWr ateel TMebeam guard& HISTORICAL INFORMATION eonmuetlondete 1922 desIgnsr/snginw Adzona Highway Dement projes number FAP 19 buildn1eon~actw Windsor, Coleman & Khg information wwce ADCYT Mge records structure owner Arizona Department of Tmnsportatlon altnakn datds) m1980 ahations steel Thrie beam guardrails lnstcrlled NATIOW REGISTER NUATION For additional informakn, sw "Vehicular Bridges in Nina1880-1964" Nebnal Reglrthr Multiple Property Dosumentation Form inventory rmre 61 NRW eligibility ebglble NRH crltsris A- 0- Cx signtf, statement excellent example of early state standard brldge hpe FORM COMRElED BY Clayton B. hr,Prindpal FRASERdeeign 420 South County Road 23E Loveland, Colorado 80537 31 October MXl4 642 FRASERDESIGN GRANITE CREEK BRIDGE ~lruclvoNa w d.t. d phota: November 20G2 visw &&en north northwest +t~N: 02.1 1.263 02.11.264 FRASERDESIGN GRANITE CREEK BRIDGE CONSTRUCTON HISTORY In 1920 the Arizona Highway Department undertook an improvement of the highway linking Prescott and Jerome. AHD designated this construction as Federal Aid Project 19, to be jointly funded by the state and the U.S. -

Historic Bridges in Arizona and Their Engineers

Historic Bridges in Arizona and Their Engineers November 3, 2011 NACE / AACE Conference Presented by: Jerry A. Cannon, PE, SE Patricia D. Morris Who Designed Arizona Bridges Mill Ave Construction Site 1928 – Photo Hoffman Collection - (Mary Lou Vaughan) Mexican American War 1848 Treaty of Hidalgo & Guadalupe Gadsden Purchase 1853 – Southern Part of AZ Northern Boundary of AZ along 37th Parallel Separated from New Mexico by 1863 Federal Organic Act Arizona Territory 1863 1846 – Cooke’s Wagon Road (Ocean to Ocean Highway US 80) Was the southern route crossing the Colorado River in Yuma Built by Capt Cooke and the Mormon Brigade during the war with Mexico. Largely paralleled the Gila River Arizona Territory Two Major Transportation Routes 1859 – Beale’s Road (Old Trails Highway and US 66) Was the northern route that crossed the Colorado River at Topock. Route was built before the construction of the railroad in 1883 Road maintenance was performed by travelers Bridges were non existent Arizona Territory Two Major Transportation Routes Alchesay Canyon Bridge (1905) Solomonville Road Overpass (1907) Lowell Arch Bridge (1911) Cameron Bridge (1911) Only Remaining Bridges from the Arizona Territory (1863-1912) Arizona’s Historic Bridges J.B. Girand 1909 - 1912 Arizona’s First and Only Territorial Engineer Florence Bridge Replacement; Lowell Bridge US80, Ash Ave. Bridge Over Salt River in Tempe Lamar Cobb 1912 Arizona’s First State Highway Engineer Antelope Hill Bridge – Yuma and Aqua Fria River Bridge Daniel Luten 1914 Canyon Padre Bridge – Canyon -

Bufo Microscaphus) in Arizona

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 53 Number 4 Article 12 12-28-1993 Distribution of the southwestern toad (Bufo microscaphus) in Arizona Brian K. Sullivan Arizona State University West, Phoenix, Arizona Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Sullivan, Brian K. (1993) "Distribution of the southwestern toad (Bufo microscaphus) in Arizona," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 53 : No. 4 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol53/iss4/12 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Great Basin Naturalist 53(4), pp. 402-406 DISTRIBUTION OF THE SOUTHWESTERN TOAD (BUFO MICROSCAPHUS) IN ARIZONA Brian K. Sullivanl Key words: Bufa microscaphus, southwestern toad, Arizona, distribution, amphibian decline, riparian habitat, hybridization. The current distribution and status of pop adult toads were found, they were measured ulations of the southwestern toad, Bufo (snout-vent length in mm, SVL), pho microscaphus, are of considerable interest tographed, and released or retained as vouch given the suspected decline in anuran er specimens (deposited in the ASU Verte amphibians in the western United States brate Collection). If larvae were present, a (Blaustein and Wake 1990, Sweet 1991). This sample was collected and returned to the lab bufonid, typically associated with riparian oratory for rearing to allow confident identifi habitats in the desert Southwest, is largely cation (larvae of Bufo woodhousii and B. -

Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Agua Fria Basin: a 2004-2006 Baseline Study

II Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Agua Fria Basin: A 2004-2006 Baseline Study By Douglas C. Towne Maps by Nicholas Moore and Jean Ann Rodine Arizona Department of Environmental Quality Open File Report 08-02 ADEQ Water Quality Division Surface Water Section Monitoring Unit 1110 West Washington St. Phoenix, Arizona 85007-2935 Thanks: Field Assistance: Elizabeth Boettcher, Aiko Condon, Karyn Hanson, Jason Jones, Angela Lucci, Meghan Smart, John Woods and Wang Yu. Special recognition is extended to the many well owners who were kind enough to give permission to collect groundwater data on their property. Photo Credits: Douglas Towne Report Cover: Groundwater pumped by a shallow well flows into a pond creating a bucolic scene on the U-Cross Ranch located north of the Town of Mayer. Situated in the floodplain of the Agua Fria River, the 52-foot-deep well produces 300 gallons per minute for irrigation, domestic and wildlife uses. Other Publications of the ADEQ Ambient Groundwater Monitoring Program ADEQ Ambient Groundwater Quality Open-File Reports (OFR): Pinal Active Management Area OFR 08-01, June 2007, 97 p. Hualapai Valley Basin OFR 07-05, March 2007, 53 p. Big Sandy Basin OFR 06-09, October 2006, 66 p. Lake Mohave Basin OFR 05-08, October 2005, 66 p. Meadview Basin OFR 05-01, January 2005, 29 p. San Simon Sub-Basin OFR 04-02, October 2004, 78 p. Detrital Valley Basin OFR 03-03, November 2003, 65 p. San Rafael Basin OFR 03-01, February 2003, 42 p. Lower San Pedro Basin OFR 02-01, July 2002, 74 p. -

NORTHERN MEXICAN GARTERSNAKE (Thamnophis Eques Megalops)

NORTHERN MEXICAN GARTERSNAKE (Thamnophis eques megalops) STATUS: Threatened SPECIES DESCRIPTION: The northern Mexican gartersnake reaches a maximum known length of 44 inches. It ranges in background color from olive to olive-brown to olive-gray. Three stripes run the length of the body with a yellow stripe down the back that darkens toward the tail. A portion of the lateral stripe occurring on the fourth scale row distinguishes T. eques from other gartersnake species. Paired black spots extend along the dorsolateral fields. A light-colored crescent extends behind the corners of the mouth. NATURAL HISTORY: This species occurs up to about 8,500 feet in elevation, but is most frequently found between 3,000 and 5,000 ft in the United States. The northern Mexican gartersnake is found in both lotic and lentic habitats that include cienegas and stock tanks (in southern Arizona), as well as river habitat that includes pools and backwaters. It forages along the banks of waterbodies feeding primarily upon native fish and adult and larval leopard frogs. It may also supplement its diet with earthworms and leeches and vertebrates such as lizards, small rodents, salamanders, treefrogs, and toads. In some populations, adult northern Mexican gartersnakes will prey upon juvenile nonnative bullfrogs and/or bullfrog tadpoles where they co-occur. Sexual maturity in male northern Mexican gartersnakes occurs at two years, and in two to three years in females. The species mates in April and May in their northern distribution, gives live birth to between seven and 38 neonates (average is 13.6) in July and August, and may only reproduce every other year. -

Agua Fria Groundwater Fact Sheet 9-08

FACT SHEET Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Agua Fria Basin: A 2004-2006 Baseline Study – July 2008 INTRODUCTION A baseline groundwater quality study of the Agua Fria basin was conducted from 2004 through 2006 by the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) Ambient Groundwater Monitoring Program. ADEQ conducted this monitoring pursuant to Arizona Revised Statutes §49-225. This fact sheet is a synopsis of the ADEQ Open File Report 08-02.1 The Agua Fria groundwater basin is located between the metropolitan areas of Phoenix and Prescott in central Arizona. The basin encompasses the drainage of the Agua Fria River from below the Prescott Active Management Area to Lake Pleasant. This lightly populated basin consists primarily of fed- eral land (U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management), State Trust land and private land including the communities of Mayer and Crown King in the Bradshaw Mountains and Cordes Junction and Black Canyon City along Interstate 17. HYDROLOGY Figure 1 – The basin’s main drainage, the Agua Fria River, is shown The basin’s main drainage is the Agua Fria River at the confluence of Badger Springs Wash. (Figure 1), which flows north to south before it reaches Lake Pleasant. Lake Pleasant was created by the new crystalline (igneous and metamorphic) rocks.2 Waddell Dam, operated by the U.S. Bureau of Although groundwater occurs in all four rock units, Reclamation, to store flow from the Agua Fria River the main water-bearing units are the basin-fill and and Colorado River water transported via the Central conglomerates; volcanic and crystalline rocks yield Arizona Project’s Hayden-Rhodes Aqueduct. -

Prescott Active Management Area

Virtual Tour Prescott AMA Active Management Area 2200 EastHillsdale Road 2200 Prescott, AZ 86301 www.azwater.gov Prescott (928) 778-7202 Prescott AMA r u o General Groundwater Facts T al u t r • New AMAs can be i • The Groundwater V Management Code was designated either by passed in June of 1980 determination by the and established the four director (45-412) or by initial Active Management petition of 10% of the Areas (AMA): Phoenix, registered voters within Tucson, Pinal and the boundary of the Prescott. proposed AMA (45-415). • The Prescott, Phoenix and • Each AMA shall have a Tucson AMAs have a goal groundwater user’s of safe-yield by 2025. advisory council (GUAC) of five members who are appointed by the Governor. 2 Prescott AMA r u o Active Management Areas (AMA) and T al Irrigation Non-expansion Areas (INA) u t r i V Arizona Prescott AMA 485 mile2 ~ 20,000 AF water use Santa Cruz AMA 750 mile2 ~ 20,000 AF water use Tucson AMA 3,800 mile2 ~ 300,000 AF water use Pinal AMA 4,000 mile2 ~ 800,000 AF water use Phoenix AMA 5,600 mile2 ~ 2 million AF water use 3 4 Virtual Tour Prescott AMA Prescott AMA r u o Prescott AMA T al u • The Prescott AMA, 100 miles t • Precipitation varies from 13 to 25 r i north & west of Phoenix, inches per year V comprises 485 square miles in central Yavapai County, Arizona • 2,900,000 acre feet of groundwater in storage in local sub-basins* • Elevation ranges from 4400’ to 7800’ above sea level • The 2003 to 2004 mean annual water-level decline rate was -2.7 • Vegetation varies from high feet* desert grasslands to conifer forests • Broad alluvial basins ringed by fault block mountains 5 *Prescott Active Management Area 2003-2004 Hydrologic Monitoring Report Prescott AMA r u o T Precipitation al u t r 25 in. -

Arizona Localities of Interest to Botanists Author(S): T

Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science Arizona Localities of Interest to Botanists Author(s): T. H. Kearney Source: Journal of the Arizona Academy of Science, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Oct., 1964), pp. 94-103 Published by: Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40022366 Accessed: 21/05/2010 20:43 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=anas. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Arizona Academy of Science. http://www.jstor.org ARIZONA LOCALITIESOF INTEREST TO BOTANISTS Compiled by T. -

Agua Fria National Monument

United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Agua Fria National Monument BLM National Landscape Conservation System FY 2011 Annual Manager’s Report Agua Fria National Monument BLM Phoenix District Office 21605 N. 7th Ave. Phoenix, AZ 85027 623-580-5500 623-580-5580 fax 1 Agua Fria National Monument Arizona BLM National Landscape Conservation System FY 2011 Annual Manager’s Report The Agua Fria National Monument is a part of the BLM's National Landscape Conservation System, the mission of which is to conserve, protect and restore nationally significant landscapes that have outstanding cultural, ecological and scientific values for present and future generations of Americans. 2 United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT – NATIONAL LANDSCAPE CONSERVATION SYSTEM – FY 2011 ANNUAL MANAGER’S REPORT Introduction This annual report encapsulates the efforts of the Agua Fria National Monument’s staff and its partners throughout Fiscal Year 2011 (October 1, 2010 – September 30, 2011). a. Unit Name: Agua Fria National Monument BLM Phoenix District Office 21605 North 7th Avenue Phoenix, Arizona 85027 623 580 5500 Agua Fria National Monument web page ***Primary Mission: Protect and sustain the extraordinary combination of cultural, natural, and scientific resources within the high desert grasslands, canyons, and streams of the Monument. To the extent consistent with resource protection, provide opportunities for scientific research, public education, interpretation, and other compatible activities. b. Manager(s): Pamela A. Mathis / Sabria Mathis / Vanessa Briceno (Acting Managers, Agua Fria National Monument) Phone: 623 580 5532 Email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] c. Hassayampa Field Office, Phoenix District, BLM Arizona d. -

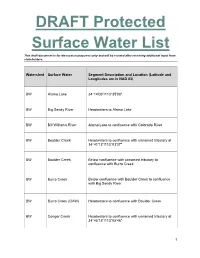

DRAFT Protected Surface Water List

DRAFT Protected Surface Water List This draft document is for discussion purposes only and will be revised after receiving additional input from stakeholders. Watershed Surface Water Segment Description and Location (Latitude and Longitudes are in NAD 83) BW Alamo Lake 34°14'06"/113°35'00" BW Big Sandy River Headwaters to Alamo Lake BW Bill Williams River Alamo Lake to confluence with Colorado River BW Boulder Creek Headwaters to confluence with unnamed tributary at 34°41'13"/113°03'37" BW Boulder Creek Below confluence with unnamed tributary to confluence with Burro Creek BW Burro Creek Below confluence with Boulder Creek to confluence with Big Sandy River BW Burro Creek (OAW) Headwaters to confluence with Boulder Creek BW Conger Creek Headwaters to confluence with unnamed tributary at 34°45'15"/113°05'46" 1 This draft document is for discussion purposes only and will be revised after receiving additional input from stakeholders. BW Conger Creek Below confluence with unnamed tributary to confluence with Burro Creek BW Copper Basin Wash Headwaters to confluence with unnamed tributary at 34°28'12"/112°35'33" BW Cottonwood Canyon Headwaters to Bear Trap Spring BW Cottonwood Canyon Below Bear Trap Spring to confluence at Smith Canyon Sycamore Creek BW Date Creek Headwaters to confluence with Santa Maria River BW Francis Creek (OAW) Headwaters to confluence with Burro Creek BW Kirkland Creek Headwaters to confluence with Santa Maria River BW Knight Creek Headwaters to confluence with Big Sandy River BW Peeples Canyon Headwaters to confluence with Santa Maria River (OAW) BW Santa Maria River Headwaters to Alamo Lake BW Trout Creek Headwaters to confluence with unnamed tributary at 35°06'47''/113°13'01'' 2 This draft document is for discussion purposes only and will be revised after receiving additional input from stakeholders.