Getting to the Green Frontier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India 2015: Towards Economic Transformation

TRANSITIONS FORUM TRANSITIONS FORUM APRIL 2015 India 2015: Towards Economic Transformation by Rajiv Kumar www.li.com www.prosperity.com 1 | ABOUT THE LEGATUM INSTITUTE The Legatum Institute is an international think-tank and educational charity focussed on promoting prosperity. We do this by researching our core themes of revitalising capitalism and democracy. The Legatum Prosperity IndexTM, our signature publication, ranks 142 countries in terms of wealth and wellbeing. Through research programmes including The Culture of Prosperity, Transitions Forum, and the Economics of Prosperity, the Institute seeks to understand what drives and restrains national success and individual flourishing. The Institute co-publishes with Foreign Policy magazine, the Democracy Lab, whose on-the-ground journalists report on political transitions around the world. The Legatum Institute is based in London and an independent member of the Legatum Group, a private investment group with a 27 year heritage of global investment in businesses and programmes that promote sustainable human development. www.li.com www.prosperity.com http://democracylab.foreignpolicy.com LEGATUM INSTITUTE 11 Charles Street Mayfair London W1J 5DW United Kingdom t: +44 (0) 20 7148 5400 In association with: Twitter: @LegatumInst www.li.com www.prosperity.com TRANSITIONS FORUM CONTENTS Introduction 2 2014: The year of historical political shift 3 The middle class as a driver of political change 5 Entitlements to empowerment and from poverty alleviation to relative prosperity 5 Modi’s economic agenda 6 Budget 2015-16 8 The way forward 9 Appendices 11 References 14 Bibliography 16 About the author inside back cover About our partners inside back cover | 1 TRANSITIONS FORUM Agra, Uttar Pradesh INTRODUCTION India is in the midst of a historical triple transition. -

March 19, 2021 Shri Jayant Sinha Chairman, Standing Committee Of

March 19, 2021 Shri Jayant Sinha Chairman, Standing committee of finance Member of Parliament [Lok Sabha] India Subject: Request for wider debate on Equalisation Levy Respected Shri Jayant Sinha ji, Our associations are a collection of the world’s most innovative companies, representing every sector of the economy. We are substantial contributors to a vibrant Indian economy. For all of us, India is an essential market in which many of our members are deeply invested, and all of our members are committed to the Government of India’s goal of making India a $5.0 trillion economy by 2025. We write to raise concerns regarding the amendment to India’s Equalisation Levy included in the Government of India’s proposed Finance Bill to the Union Budget 2021-22. As detailed below, the amendment would create significant challenges for all businesses operating in India, further exacerbating the detrimental impact of a measure at odds with India’s ongoing commitment to the multilateral negotiations at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)/G20 Inclusive Framework to address the tax challenges arising from the digitalisation of the global economy. The G20 Finance Ministers – including Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman – reiterated as recently as February 26 their support for the Inclusive Framework’s timeline of realising a multilateral, consensus- based agreement by mid-2021. It is in the spirit of support for a multilateral solution that we encourage the Parliament to refrain from adopting the amendment proposed to sections 163-165A of the Finance Act, 2016, which, despite its characterization by the Ministry of Finance as clarifications and an amendment, would fundamentally expand the scope of the Equalisation Levy and generate a range of new compliance questions and concerns. -

The New World Order

The New World Order ADVERTORIAL Kamini.Kulshreshtha @timesgroup.com n the second day of the 3rd National Leadership OConclave of All India Management Association in New Delhi, Suresh Prabhu, Minister of Railways, Government of India while speaking on the topic 'Driving Indian Economy: Railways as a Growth Engine', talked extensively about how Indian Railways is working towards strengthening the country's economy and how Asia has dominated the world for a long time. "Asia has an ancient culture and growth cannot happen without a deep-rooted culture. Asia is one continent but not one union unlike most other continents. We must segment Asia and see where most of this growth will come (L-R) Sangita Reddy, Joint Managing Director, Apollo Hospitals Enterprise Ltd; Suresh Prabhu, Minister of (L-R) Rekha Sethi, Director General, AIMA; Sanjiv Goenka, Conclave Chairman and Chairman, RP-Sanjiv Goenka Group; Rajiv Pratap Rudy, Minister of from. I am sure India has a Railways, Government of India and Sanjiv Goenka, Conclave Chairman and Chairman, RP-Sanjiv Goenka State Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (IC), Government of India; Sunil Kant Munjal, President, AIMA and Chairman, Hero Corporate Service and T great role to play," he said. Group V Mohandas Pai, Senior Vice President, AIMA and Chairperson, Manipal Global Education Services country, but now with new On the second day of the Leading through Music', Ustad initiatives, things are changing. conclave, the welcome address Amjad Ali Khan, Sarod Virtuoso We need to create a functional was delivered by Sunil Kant & Composer, along with his India: Moving ahead with times skill system. -

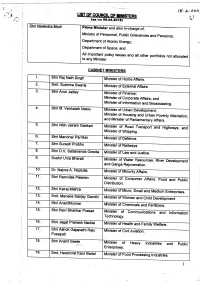

Ljitof Cqmnctl Qf MRISTSRS· ()

• . 15·.:L·21l/11 >LJITOf CQMNCtL Qf MRISTSRS· () . (aa 011 OS.03.201 S) Shri Narendra·Modi Prime Minister and also in-charge of: Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions; Department of Atomic Energy; Department of Space; and All important policy issues and all other portfolios not allocated to any Minister. CABINET MINISTERS 1. ·' Shri R~j Nath Singh Minister of Home Affairs. 2. Smt. Sushma Swaraj Minister of External Affairs . 3. .· Shri Arun Jaitley Minister of Finance; Minister of Corporate Affairs; and Minister of Information and Broadcasting. 4. Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu Minister of Urban Development; Minister of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation; and Minister of Parliamentary Affairs. 5. Shri Nitin Jairam Gadkari Minister of Road Transport and Highways; and Minister of Shipping. 6. Shri Manohar Parrikar Minister of Defence. 7. Shri Si.JreshPrabhu Minister of Railways. 8. Shri D.V. Sadananda Gowda Minister of Law and Justice. 9. Sushri UrnaBharatl Minister of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation. 10. Dr; Najma A. Heptulla Minister of Minority Affairs. 11. Shri Ramvilas Paswan Minister of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. 12. Shri Kalraj Mishra Minister of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. 13. Smt. Maneka Sanjay Gandhi Minister of Women and Child Development. 14. Shri Ananthkumar Minister of Chemicals and Fertilizers. 15. Shri Ravi Shankar Prasad Minister of Communications and Information Technology. 16. Shri Jagat Prakash·Nadda Minister of Health and Family Welfare. 17. Shri Ashok Gajapathi Raju Minister of Civil Aviation. Pusapati 18. Shri Anant Geete Minister of •...--····~·- Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises. 19. Smt. Harsimrat Kaur Badal Minister of Food Processing Industries. -

Rajya Sabha —— Revised List of Business

RAJYA SABHA —— REVISED LIST OF BUSINESS Tuesday, December 6, 2016 11 A.M. ———— PAPERS TO BE LAID ON THE TABLE I. Following Ministers to lay papers on the Table entered in the separate list: — 1. SHRI JAGAT PRAKASH NADDA for Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2. SHRI SHRIPAD YESSO NAIK for Ministry of AYUSH; 3. SHRI SANTOSH KUMAR GANGWAR for Ministry of Finance; 4. SHRI FAGGAN SINGH KULASTE for Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 5. SHRI JAYANT SINHA for Ministry of Civil Aviation; 6. SHRI ARJUN RAM MEGHWAL for Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Corporate Affairs; and 7. DR. SUBHASH RAMRAO BHAMRE for Ministry of Defence. II. SHRI ARJUN RAM MEGHWAL to lay on the Table, under clause (1) of article 151 of the Constitution, a copy (in English and Hindi) of the Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Restructured Accelerated Power Development and Reforms Programme - Union Government, Ministry of Power, Report No.30 of 2016 (Performance Audit) ———— STATEMENT BY MINISTER SHRI JAGAT PRAKASH NADDA to make a statement regarding status of implementation of recommendations contained in the Seventy-first and Eighty-eighth Reports of the Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare on the functioning of Central Government Health Scheme (CGHS). ———— #QUESTIONS QUESTIONS entered in separate lists to be asked and answers given. ———— @SUPPLEMENTARY DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (GENERAL) 2016-17 SHRI ARUN JAITLEY to lay on the Table, a statement (in English and Hindi) showing the Supplementary Demands for Grants (General) 2016-17. ———— # At 12 Noon. @ At 2-00 P.M. -

Government of India Ministry of Commerce & Industry

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY DEPARTMENT FOR PROMOTION OF INDUSTRY AND INTERNAL TRADE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 3763. TO BE ANSWERED ON WEDNESDAY, THE 11TH DECEMBER, 2019. IT PATENT 3763. SHRI JAYANT SINHA: Will the Minister of COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY be pleased to state: वाणि煍य एवं उ饍योग मंत्री (a) the number of international Information Technology (IT) patent requests filed by Indian citizens in the year 2018-2019 and the country’s rank globally in patents filed in the IT sector; (b) whether the Government is taking measures to encourage patent filing by individuals or organisations in the IT sector, and if so, the details thereof; and (c) the number of functional startup incubation centres, State/UT-wise and the number of technological startups incubated by the Government so far, State/UT-wise? ANSWER वाणिज्य एवं उ饍योग मंत्री (श्री पीयूष गोयल) THE MINISTER OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY (SHRI PIYUSH GOYAL) (a): As per information available with Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (CGPDTM), a total of 5,852 requests seeking permission for filing applications outside India were received during 2018-19. Out of this, 3,522 requests were from Information Technology (IT) sector. Further, 966 International applications under Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) were filed during 2018-19 by Indian applicants at Indian Patent Office with a request to forward the same to World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Besides, 1,061 International applications under PCT were filed by Indian applicants directly to WIPO. India’s ranking in PCT Filing is 13th during the year 2018 as per WIPO Report. -

To, Hon'ble Shr I Arun Jaitley Minister of Finance Government of India North Block, New Delhi

19th February, 2016 To, Hon’ble Shr I Arun Jaitley Minister of Finance Government of India North Block, New Delhi – 110001. Dear Sir, Sub: Representation in respect of Income Computation and Disclosure Standards [ICDS] We enclose herewith our representation and suggestions in respect of implementation of ICDS, for your consideration. We sincerely hope that our representation would receive favourable consideration. Thanking you, We remain, Yours truly, For Bombay Chartered Accountants' Society Raman Jokhakar Sanjeev R. Pandit Ameet Patel President Chairman Co-Chairman Taxation Committee Taxation Committee Copy to: 1. Shri Jayant Sinha, Minister of State for Finance . 2. Dr. Hasmukh Adhia, Revenue Secretary. 3. Shri Atulesh Jindal, Chairman, CBDT. 4. Shri Kirit Somaiya, Member of Parliament . Bombay Chartered Accountants’ Society Representation regarding Income Computation and Disclosure Standards The present Government took office promising to end `tax terrorism’ and providing an environment fostering ease of doing business. The Income Computation and Disclosure Standards (ICDS) will certainly not make it easy for doing business in India. The Government should take into account valid concerns, genuine fears of the taxpaying community and far-reaching effects of the ICDS before implementing the ICDS. A large number of provisions contained in the ICDS accelerate the taxation either by taxing income before it is recorded in the books of account or by not allowing losses recorded in books of account as per well recognised commercial practices and the Accounting Standards prescribed by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India or those notified by the Government for companies. This will only widen the difference between the accounting profits and taxable income and increase timing differences resulting insubstantial increase in cost of compliance without any substantial benefit on an overall basis. -

Council of Ministers

COUNCILOFMINISTERS (1947-2015) NAMESANDPORTFOLIOSOFTHEMEMBERS OF THEUNIONCOUNCILOFMINISTERS (From15August1947to28August2015 ) LOKSABHASECRETARIAT NEWDELHI 2016 LARRDIS/REFERENCE 2016 First Edition : 1968 Second Edition : 1978 Third Edition : 1985 Reprint : 1987 Fourth Edition : 1990 Fifth Edition : 1997 Sixth Edition : 2004 Seventh Edition : 2011 Eighth Edition : 2016 Price : R 500.00 $ 7.50 £ 6.00 © 2016 BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fifteenth Edition) and printed by Aegean Offset Printers, New Delhi. PREFACE ThisbrochureprovidesinformationonMembersoftheUnionCouncil ofMinistersandtheirportfoliossince15August1947.Thebrochurewas firstpublishedinMay1968andthepresentupdatededitionistheeighth oneintheseries,whichcontainsinformationfortheperiodfrom 15August1947to28August2015. InformationonthenumberofMinistersineachcategory,tenuresofall PrimeMinistersandthechangeseffectedintheUnionCouncilofMinisters fromtimetotimehasbeenincorporatedintheIntroduction. ThisbrochureisdividedintosevenParts.PartIdealswiththe PrimeMinisterssinceIndependence;PartIIcontainsinformationonthe MinisterialcareerofthosewhobecameDeputyPrimeMinisters;PartIII givesthenamesofCabinetMinisters;PartIVenumeratesMinistersof CabinetrankbutwhowerenotmembersoftheCabinet;PartVcontains informationaboutMinistersofStatewithindependentchargeoftheir Ministries/Departments;PartVIindicatesnamesoftheMinistersofState attachedtothePrimeMinisterandCabinetMinisters;andPartVIIliststhe namesofDeputyMinistersandParliamentarySecretariesholdingtherank -

Rajya Sabha —— Revised List of Business

RAJYA SABHA —— REVISED LIST OF BUSINESS Tuesday, August 9, 2016 11 A.M. ———— PAPERS TO BE LAID ON THE TABLE Following Ministers to lay papers on the Table entered in the separate list: — 1. SHRI SHRIPAD YESSO NAIK for Ministry of AYUSH; 2. SHRI SANTOSH KUMAR GANGWAR for Ministry of Finance; 3. SHRI FAGGAN SINGH KULASTE for Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 4. SHRI JAYANT SINHA for Ministry of Civil Aviation; 5. SHRI ARJUN RAM MEGHWAL for Ministry of Corporate Affairs and Ministry of Finance; and 6. DR. SUBHASH RAMRAO BHAMRE for Ministry of Defence. ———— REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT DR. SATYANARAYAN JATIYA SHRI PARTAP SINGH BAJWA to present the Two Hundred Eighty- First Report (in English and Hindi) of the Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Human Resource Development on the subject 'Performance of National Sports Development Fund and Recruitment and Promotion of Sportspersons -(Part-III)'. ———— STATEMENT BY MINISTER SHRI JAYANT SINHA to make a statement regarding Status of implementation of recommendations contained in the Two Hundred and Twenty- fifth Report of the Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Transport, Tourism and Culture on the Demands for Grants pertaining to the Ministry of Civil Aviation. ———— MOTION FOR ELECTION TO THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON OFFICES OF PROFIT SHRI RAVI SHANKAR PRASAD to move the following Motion:— “That this House concurs in the recommendation of the Lok Sabha that the Rajya Sabha do elect one Member of the Rajya Sabha to the Joint Committee on Offices of Profit in the vacancy caused by the retirement of Shri K.C. -

Getting to the Green Frontier Faster

GETTINGGETTING TOTO THETHE GREENGREEN FRONTIERFRONTIER FASTERFASTER THE CASE FOR A GREEN FRONTIER SUPERFUND JAYANT SINHA TANUSHREE CHANDRA GETTING TO THE GREEN FRONTIER FASTER THE CASE FOR A GREEN FRONTIER SUPERFUND Jayant Sinha Tanushree Chandra © 2020 Observer Research Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from ORF. Attribution Jayant Sinha and Tanushree Chandra, Getting to the Green Frontier Faster: The Case for a SuperFund, July 2020, Observer Research Foundation Observer Research Foundation 20 Rouse Avenue, Institutional Area New Delhi, India 110002 [email protected] www.orfonline.org ORF provides non-partisan, independent analyses and inputs on matters of security, strategy, economy, development, energy and global governance to diverse decision-makers (governments, business communities, academia and civil society). ORF’s mandate is to conduct in-depth research, provide inclusive platforms, and invest in tomorrow’s thought leaders today. This report was prepared with support from the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation. The recommendations and the views expressed herein are, however, those of the authors and do not reflect the formal position of the Foundation. Design and layout: Rahil Miya Shaikh Disclaimer: This report presents information and data that was compiled and/or collected by the Observer Research Foundation. Data in this report is subject to change without notice. Although the ORF takes every -

IDFC Updates Shareholders and Bondholders on Impact of Demerger

IDFC updates shareholders and bondholders on impact of demerger Mumbai, October 29, 2015: IDFC Ltd, the country’s leading integrated infrastructure finance company, today reiterated the impact of its demerger to shareholders and bondholders, in an email sent to them. This is part of IDFC’s effort to keep investors informed and address queries on the demerger through written communication ([email protected]), its toll free number (180030004332) and FAQs on its website www.idfc.com. The Reserve Bank of India granted a universal banking license to IDFC Limited on July 23, 2015. IDFC Ltd. demerged on October 1, 2015, transferring all assets and liabilities of its lending business (“Financing Undertaking”) to IDFC Bank Limited. IDFC Bank started operations on October 1, 2015. It was formally inaugurated on October 19, 2015, by the Hon’ble Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi in New Delhi. The Hon’ble Finance Minister, Shri Arun Jaitley, and the Hon’ble Minister of State for Finance, Shri Jayant Sinha, were also present at the inaugural ceremony. Shareholders of IDFC as on the record date i.e. October 5, 2015, as per the scheme of demerger approved by the Hon’ble Chennai High Court, have received an equivalent number of IDFC Bank shares (free of cost). IDFC shares are now trading ex-bank and IDFC Bank shares are not yet listed and traded. In the email sent to shareholders today, IDFC said that the IDFC Bank shares are expected to list and trade on November 6, 2015. Shareholders will have to wait for IDFC Bank shares to list and trade to evaluate the value of their combined IDFC and IDFC Bank shareholding. -

India - Japan Relations

India - Japan Relations The friendship between India and Japan has a long history rooted in spiritual affinity and strong cultural and civilizational ties. India’s earliest documented direct contact with Japan was with the Todaiji Temple in Nara, where the consecration or eye-opening of the towering statue of Lord Buddha was performed by an Indian monk, Bodhisena, in 752 AD. In contemporary times, among prominent Indians associated with Japan were Swami Vivekananda, Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore, JRD Tata, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose and Judge Radha Binod Pal. The Japan-India Association was set up in 1903, and is today the oldest international friendship body in Japan. Throughout the various phases of history since contacts between India and Japan began some 1400 years ago, the two countries have never been adversaries. Bilateral ties have been singularly free of any kind of dispute – ideological, cultural or territorial. Post the Second World War, India did not attend the San Francisco Conference, but decided to conclude a separate peace treaty with Japan in 1952 after its sovereignty was fully restored. The sole dissenting voice of Judge Radha Binod Pal at the War Crimes Tribunal struck a deep chord among the Japanese public that continues to reverberate to this day. The modern nation States have carried on the positive legacy of the old association which has been strengthened by shared values of belief in democracy, individual freedom and the rule of law. Over the years, the two countries have built upon these values and created a partnership based on both principle and pragmatism. Today, India is the largest democracy in Asia and Japan the most prosperous.