Media Students/0I/C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

INDEX A Bertsch, Fred, 16 Caslon Italic, 86 accents, 224 Best, Mark, 87 Caslon Openface, 68 Adobe Bickham Script Pro, 30, 208 Betz, Jennifer, 292 Cassandre, A. M., 87 Adobe Caslon Pro, 40 Bézier curve, 281 Cassidy, Brian, 268, 279 Adobe InDesign soft ware, 116, 128, 130, 163, Bible, 6–7 casual scripts typeface design, 44 168, 173, 175, 182, 188, 190, 195, 218 Bickham Script Pro, 43 cave drawing, type development, 3–4 Adobe Minion Pro, 195 Bilardello, Robin, 122 Caxton, 110 Adobe Systems, 20, 29 Binner Gothic, 92 centered type alignment Adobe Text Composer, 173 Birch, 95 formatting, 114–15, 116 Adobe Wood Type Ornaments, 229 bitmapped (screen) fonts, 28–29 horizontal alignment, 168–69 AIDS awareness, 79 Black, Kathleen, 233 Century, 189 Akuin, Vincent, 157 black letter typeface design, 45 Chan, Derek, 132 Alexander Isley, Inc., 138 Black Sabbath, 96 Chantry, Art, 84, 121, 140, 148 Alfon, 71 Blake, Marty, 90, 92, 95, 140, 204 character, glyph compared, 49 alignment block type project, 62–63 character parts, typeface design, 38–39 fi ne-tuning, 167–71 Blok Design, 141 character relationships, kerning, spacing formatting, 114–23 Bodoni, 95, 99 considerations, 187–89 alternate characters, refi nement, 208 Bodoni, Giambattista, 14, 15 Charlemagne, 206 American Type Founders (ATF), 16 boldface, hierarchy and emphasis technique, China, type development, 5 Amnesty International, 246 143 Cholla typeface family, 122 A N D, 150, 225 boustrophedon, Greek alphabet, 5 circle P (sound recording copyright And Atelier, 139 bowl symbol), 223 angled brackets, -

Graphics Design

Graphics Design - Typography Exercise 7 - ‘Arial’ ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Closest Fonts: {Arial, Helvetica, MS Gothic} Closer Fonts: {Newhouse DT Condensed, CG Triumvirate Condensed} Chosen Focus Font: {Arial Narrow Bold Italic} ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Font: Monotype Grotesque Birth-Date: 1926 Creator: Frank Hinman Pierpont Publisher: Monotype Foundry Based Off: Grotesque (by H. Berthold AG Foundry & William Thorowogood, 1832) Family: Largely-Extended: Multiple Widths (Condensed,...,Extended) Recognition: Easily Recognisable as san-serifs were few and unusual in England. Use: Early 20th Century Avant Garde Printing from Western & Central Europe ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Font: Arial Alias: (Original) Sonoran Sans Serif, (After Microsoft Acquisition) Arial MT Birth-Date: 1982 Self-Description: “Contemporary sans serif design, Arial contains more humanist characteristics than many of its predecessors and as such is more in tune with the mood of the last decades of the twentieth century. The overall treatment of curves is softer and fuller than in most industrial style sans serif faces. Terminal strokes are cut on the diagonal which helps to give the face a less mechanical appearance. Arial is an extremely versatile family of typefaces which can -

Apple Lisa Computer Font Charts

Apple Lisa Computer Font Charts Apple Lisa Computer Technical Information APPLE LISA COMPUTER FONT CHARTS Printed by David T. Craig Printed by: Macintosh Picture Printer 0.0.2 1998-12-06 Printed: 1998-12-15 17:06:07 Printed by David T. Craig Page 0000 of 0028 Apple Lisa Computer Font Charts Printed by David T. Craig Page 0001 of 0028 “Apple Lisa Font Chart 01/28.PIC” 16 KB 1998-12-13 dpi: 72h x 72v pix: 576h x 720v Apple Lisa Computer Font Charts Printed by David T. Craig Page 0002 of 0028 “Apple Lisa Font Chart 02/28.PIC” 22 KB 1998-12-13 dpi: 72h x 72v pix: 576h x 720v Apple Lisa Computer Font Charts Printed by David T. Craig Page 0003 of 0028 “Apple Lisa Font Chart 03/28.PIC” 12 KB 1998-12-13 dpi: 72h x 72v pix: 576h x 720v Apple Lisa Computer Font Charts Printed by David T. Craig Page 0004 of 0028 “Apple Lisa Font Chart 04/28.PIC” 14 KB 1998-12-13 dpi: 72h x 72v pix: 576h x 720v Apple Lisa Computer Font Charts Printed by David T. Craig Page 0005 of 0028 “Apple Lisa Font Chart 05/28.PIC” 16 KB 1998-12-13 dpi: 72h x 72v pix: 576h x 720v Apple Lisa Computer Font Charts Printed by David T. Craig Page 0006 of 0028 “Apple Lisa Font Chart 06/28.PIC” 21 KB 1998-12-13 dpi: 72h x 72v pix: 576h x 720v Apple Lisa Computer Font Charts Printed by David T. -

Kjell Specimen Page 1 / 6

10 KJELL SPECIMEN PAGE 1 / 6 Kjell - Synthesis of opposites Kjell is a conceptual display typeface balanc- Fear. ing between its two extremes. The typeface combining two different faces - the »Fear« and »Truth« weight, which are made out of Kjell one stem. Inspired by the 14th tarot card of temper- ance, Kjell understands itself as a synthesis of its two opposites, which are representing Truth. a process of harmonization. Both of the extremes have their details – while the »Fear« extreme is characterized Kjell through deep ink traps, the »Truth« extreme appears more softly with its rounded edges. Both extremes are characterized by their de- tails and are duel each other. Referring to its architecture and appearance, Kjell is intended as a display font. With its extensive set of glyphs, it is multilingual and contains a large number of accents, punctua- tion, symbols and special characters. Designer Armin Brenner, Markus John Year 2021 Styles Truth & Fear Licenses Desktop, Web, App (on request) Copyright © NEW LETTERS, All rights reserved NEW LETTERS www.new-letters.de 10 KJELL SPECIMEN PAGE 2 / 6 FEAR characterset Lowercase aáăâäàāąåãæċćčçďđéěêëėèēęğġģħıíîïìīįķĺľļŀłŋńňņñ óôöòőōøõœþŕřŗșśšşțŧťţúûüùűūųůẃŵẅẁýŷÿỳźžż Uppercase ÁĂÂÄÀĀĄÅÃÆĆČÇĊÐĎĐÉĚÊËĖÈĒĘĞĢĠĦÍÎÏİÌĪĮĶĹĽĻŁŃŇŅ ŊÑÓÔÖÒŐŌØÕŒÞŔŘŖŚŠŞȘẞŦŤŢȚÚÛÜÙŰŪŲŮẂŴẄẀÝ ŶŸỲŹŽŻ Numerals and Fractions 0123456789¼½¾ Ligatures fi jj Arrows →←↑↓↗↖↘↙ Punctuations —-–«»‹›„“”‘’‚≈~÷+±=>≥<≤−×≠|¦°^◊´ˇˆ¨˙`˝†‡˚˜¯•;:,… .·”’/\_{}[]()* Symbols and more ¢$€£¥√¤ð¶§@®©™ª∞∫ƒ∂∏∑&ßẞ!¡?¿#%‰����� NEW LETTERS www.new-letters.de -

Type Design for Typewriters: Olivetti by María Ramos Silva

Type design for typewriters: Olivetti by María Ramos Silva Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MA in Typeface Design Department of Typography & Graphic Communication University of Reading, United Kingdom September 2015 The word utopia is the most convenient way to sell off what one has not the will, ability, or courage to do. A dream seems like a dream until one begin to work on it. Only then it becomes a goal, which is something infinitely bigger.1 -- Adriano Olivetti. 1 Original text: ‘Il termine utopia è la maniera più comoda per liquidare quello che non si ha voglia, capacità, o coraggio di fare. Un sogno sembra un sogno fino a quando non si comincia da qualche parte, solo allora diventa un proposito, cio è qualcosa di infinitamente più grande.’ Source: fondazioneadrianolivetti.it. -- Abstract The history of the typewriter has been covered by writers and researchers. However, the interest shown in the origin of the machine has not revealed a further interest in one of the true reasons of its existence, the printed letters. The following pages try to bring some light on this part of the history of type design, typewriter typefaces. The research focused on a particular company, Olivetti, one of the most important typewriter manufacturers. The first two sections describe the context for the main topic. These introductory pages explain briefly the history of the typewriter and highlight the particular facts that led Olivetti on its way to success. The next section, ‘Typewriters and text composition’, creates a link between the historical background and the machine. -

Frutiger (Tipo De Letra) Portal De La Comunidad Actualidad Frutiger Es Una Familia Tipográfica

Iniciar sesión / crear cuenta Artículo Discusión Leer Editar Ver historial Buscar La Fundación Wikimedia está celebrando un referéndum para reunir más información [Ayúdanos traduciendo.] acerca del desarrollo y utilización de una característica optativa y personal de ocultamiento de imágenes. Aprende más y comparte tu punto de vista. Portada Frutiger (tipo de letra) Portal de la comunidad Actualidad Frutiger es una familia tipográfica. Su creador fue el diseñador Adrian Frutiger, suizo nacido en 1928, es uno de los Cambios recientes tipógrafos más prestigiosos del siglo XX. Páginas nuevas El nombre de Frutiger comprende una serie de tipos de letra ideados por el tipógrafo suizo Adrian Frutiger. La primera Página aleatoria Frutiger fue creada a partir del encargo que recibió el tipógrafo, en 1968. Se trataba de diseñar el proyecto de Ayuda señalización de un aeropuerto que se estaba construyendo, el aeropuerto Charles de Gaulle en París. Aunque se Donaciones trataba de una tipografía de palo seco, más tarde se fue ampliando y actualmente consta también de una Frutiger Notificar un error serif y modelos ornamentales de Frutiger. Imprimir/exportar 1 Crear un libro 2 Descargar como PDF 3 Versión para imprimir Contenido [ocultar] Herramientas 1 El nacimiento de un carácter tipográfico de señalización * Diseñador: Adrian Frutiger * Categoría:Palo seco(Thibaudeau, Lineal En otros idiomas 2 Análisis de la tipografía Frutiger (Novarese-DIN 16518) Humanista (Vox- Català 3 Tipos de Frutiger y familias ATypt) * Año: 1976 Deutsch 3.1 Frutiger (1976) -

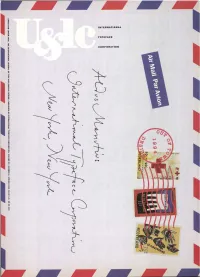

INTERNATIONAL TYPEFACE CORPORATION, to an Insightful 866 SECOND AVENUE, 18 Editorial Mix

INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION TYPEFACE UPPER AND LOWER CASE , THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF T YPE AND GRAPHI C DESIGN , PUBLI SHED BY I NTE RN ATIONAL TYPEFAC E CORPORATION . VO LUME 2 0 , NUMBER 4 , SPRING 1994 . $5 .00 U .S . $9 .90 AUD Adobe, Bitstream &AutologicTogether On One CD-ROM. C5tta 15000L Juniper, Wm Utopia, A d a, :Viabe Fort Collection. Birc , Btarkaok, On, Pcetita Nadel-ma, Poplar. Telma, Willow are tradmarks of Adobe System 1 *animated oh. • be oglitered nt certain Mrisdictions. Agfa, Boris and Cali Graphic ate registered te a Ten fonts non is a trademark of AGFA Elaision Miles in Womb* is a ma alkali of Alpha lanida is a registered trademark of Bigelow and Holmes. Charm. Ea ha Fowl Is. sent With the purchase of the Autologic APS- Stempel Schnei Ilk and Weiss are registimi trademarks afF mdi riot 11 atea hmthille TypeScriber CD from FontHaus, you can - Berthold Easkertille Rook, Berthold Bodoni. Berthold Coy, Bertha', d i i Book, Chottiana. Colas Larger. Fermata, Berthold Garauannt, Berthold Imago a nd Noire! end tradematts of Bern select 10 FREE FONTS from the over 130 outs Berthold Bodoni Old Face. AG Book Rounded, Imaleaa rd, forma* a. Comas. AG Old Face, Poppl Autologic typefaces available. Below is Post liedimiti, AG Sitoploal, Berthold Sr tapt sad Berthold IS albami Book art tr just a sampling of this range. Itt, .11, Armed is a trademark of Haas. ITC American T}pewmer ITi A, 31n. Garde at. Bantam, ITC Reogutat. Bmigmat Buick Cad Malt, HY Bis.5155a5, ITC Caslot '2114, (11 imam. -

Download Free Typewriter Font 14 Fun Fonts to Put a Smile on Your Face

download free typewriter font 14 fun fonts to put a smile on your face. Who doesn't want a bunch of fun fonts to cheer up their projects? The good news is there's almost an endless supply of friendly, happy fonts whirling around the web, and we've picked out the best ones available, for an injection of fun typography into your work. The fun fonts on the list below have a range of price points and have been selected by us – whether that's 'cos they are funny fonts, exciting fonts, friendly fonts or they just make us happy. With the list below, you're sure to be able to find the best fun font for your project (and don't worry – Comic Sans didn't make the cut). If you want something slightly different, then don't miss our selection of top retro fonts, free script fonts or calligraphy fonts. 01. Balgin. Balgin is here to take you back to the '90s for a dose of nostalgic fun. This happy font designed by Cahya Sofyan is formed from basic shapes and is available in three 'flavours' – display, normal and text and six different weights. It supports over 75 languages and we just love its bright and friendly look – the very definition of fun typography. It's available from £7.99. 02. Mohr Rounded. A curvier version of the Mohr typeface, this fun font features soft terminals for a friendly look. The family includes three versions (normal, alt and italic) in a wide range of weights, making it nice and versatile. -

52Nd California International Antiquarian Book Fair List

52nd California International Antiquarian Book Fair List February 8 thru 10, 2019 John Howell for Books John Howell, member ABAA, ILAB, IOBA 5205 ½ Village Green, Los Angeles, CA 90016-5207 310 367-9720 www.johnhowellforbooks.com [email protected] THE FINE PRINT: All items offered subject to prior sale. Call or e-mail to reserve, or visit us at www.johnhowellforbooks.com, where all the items offered here are available for purchase by Credit Card or PayPal. Checks payable to John Howell for Books. Paypal payments to: [email protected]. All items are guaranteed as described. Items may be returned within 10 days of receipt for any reason with prior notice to me. Prices quoted are in US Dollars. California residents will be charged applicable sales taxes. We request prepayment by new customers. Institutional requirements can be accommodated. Inquire for trade courtesies. Shipping and handling additional. All items shipped via insured USPS Mail. Expedited shipping available upon request at cost. Standard domestic shipping is $ 5.00 for a typical octavo volume; additional items $ 2.00 each. Large or heavy items may require additional postage. We actively solicit offers of books to purchase, including estates, collections and consignments. Please inquire. This list prepared for the 52nd California International Antiquarian Book Fair, coming up the weekend of February 4 thru 11, 2019 in Oakland, California, contains 36 items including fine press material, leaf books, typography, and California history. Look for me in Booth 914, for more interesting material. John Howell for Books !3 1 [Ashendene Press] ASSISI, Francesco di (1181-1226). I Fioretti del Glorioso Poverello di Cristo S. -

Study on the Application of Chinese Fonts in the Computer Shen-Ao

2017 4th International Conference on Social Science (ICSS 2017) ISBN: 978-1-60595-525-4 Study on the Application of Chinese Fonts in the Computer Shen-Ao LIU Wuhan, Hubei, China, Hubei University of Technology [email protected] Keywords: Computer, Font library, Printing fonts, Design application Abstract. A font library is a collection of fonts with different shapes but the same styles, sizes, and forms. It is made based on the number of Chinese characters and the standard of font shape in accordance with the regulations of our country, and there is no originality in choosing and arranging the contents and number of fonts. Therefore, a computer font library is not a compiled work, but a database, a frequently used computer font library. By the end of the 1980s, the computer font library has basically replaced the traditional type printing, accelerating the diversification of China's print fonts design. This paper discusses the design and creation of computer font libraries and the diversification of fonts design, and explores the application of computer fonts in the press and multimedia. Introduction By the end of 1980s, the type printing technology which has been used in China for nearly a hundred years has been replaced by laser typesetting, computer font library, and computer typesetting technology. China’s printing industry bade farewell to the era of lead and fire and ushered in a technological revolution featuring light and electricity. The computer font library of Chinese characters firstly entering in printing and typesetting was developed and used. The design of printing fonts through computer is convenient and fast, and has various art forms. -

Contemporary Processes of Text Typeface Design

Title Contemporary processes of text typeface design Type The sis URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/13455/ Dat e 2 0 1 8 Citation Harkins, Michael (2018) Contemporary processes of text typeface design. PhD thesis, University of the Arts London. Cr e a to rs Harkins, Michael Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Contemporary processes of text typeface design Michael Harkins Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Central Saint Martins University of the Arts London April 2018 This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my brother, Lee Anthony Harkins 22.01.17† and my father, Michael Harkins 11.04.17† Abstract Abstract Text typeface design can often be a lengthy and solitary endeavour on the part of the designer. An endeavour for which, there is little in terms of guidance to draw upon regarding the design processes involved. This is not only a contemporary problem but also an historical one. Examination of extant accounts that reference text typeface design aided the orientation of this research (Literature Review 2.0). This identified the lack of documented knowledge specific to the design processes involved. Identifying expert and non-expert/emic and etic (Pike 1967) perspectives within the existing literature helped account for such paucity. In relation to this, the main research question developed is: Can knowledge of text typeface design process be revealed, and if so can this be explicated theoretically? A qualitative, Grounded Theory Methodology (Glaser & Strauss 1967) was adopted (Methodology 3.0), appropriate where often a ‘topic of interest has been relatively ignored in the literature’ (Goulding 2002, p.55). -

Portrait Family Specimen

Portrait Portrait started out as an experiment in drawing a display typeface that manages to be both beautiful and brutal, and both classical and modern in its minimalism. While its lighter weights are quietly elegant, the heavier weights show the influence of chiseled woodcut forms. PUBLISHED 2013 Portrait draws its primary inspiration from the Two-line Double Pica Roman, equivalent to 32pt in contemporary sizes, DESIGNED BY BERTON HASEBE attributed to the French punchcutter Maître Constantin 12 STYLES (known as the ‘Estienne Master’) around 1530 for the printer 6 WEIGHTS W/ ITALICS Robert Estienne in Paris. This was the earliest Roman typeface FEATURES PROPORTIONAL OLDSTYLE/LINING FIGURES with a lowercase to be cut in such a large size, and its light, SMALL CAPITALS (ROMANS) FRACTIONS delicate forms were a major influence on the large types cut SUPERSCRIPT/SUBSCRIPT by many punchcutters of the era, including Augereau and his apprentice Garamont. Portrait replaces the delicately modeled serif treatment of Constantin’s original with simple, triangular Latin serifs, reimagining the Renaissance forms in a contempo- rary light. The italic is a departure from the historical models, touching on hallmarks of the style, like the slightly ascending p and looped k, while remaining minimalist in nature, turning hooks into triangles and regularizing the slope angle. Commercial commercialtype.com Portrait 2 of 26 Portrait Light Portrait Light Italic Portrait Regular Portrait Regular Italic Portrait Regular No.2 Portrait Regular No.2 Italic Portrait