Rahul Dravid Speech – Sir Donald Bradman Oration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captain Cool: the MS Dhoni Story

Captain Cool The MS Dhoni Story GULU Ezekiel is one of India’s best known sports writers and authors with nearly forty years of experience in print, TV, radio and internet. He has previously been Sports Editor at Asian Age, NDTV and indya.com and is the author of over a dozen sports books on cricket, the Olympics and table tennis. Gulu has also contributed extensively to sports books published from India, England and Australia and has written for over a hundred publications worldwide since his first article was published in 1980. Based in New Delhi from 1991, in August 2001 Gulu launched GE Features, a features and syndication service which has syndicated columns by Sir Richard Hadlee and Jacques Kallis (cricket) Mahesh Bhupathi (tennis) and Ajit Pal Singh (hockey) among others. He is also a familiar face on TV where he is a guest expert on numerous Indian news channels as well as on foreign channels and radio stations. This is his first book for Westland Limited and is the fourth revised and updated edition of the book first published in September 2008 and follows the third edition released in September 2013. Website: www.guluzekiel.com Twitter: @gulu1959 First Published by Westland Publications Private Limited in 2008 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland and the Westland logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Text Copyright © Gulu Ezekiel, 2008 ISBN: 9788193655641 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. -

Partnership Act 1963

Australian Capital Territory Partnership Act 1963 A1963-5 Republication No 10 Effective: 14 October 2015 Republication date: 14 October 2015 Last amendment made by A2015-33 Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel About this republication The republished law This is a republication of the Partnership Act 1963 (including any amendment made under the Legislation Act 2001, part 11.3 (Editorial changes)) as in force on 14 October 2015. It also includes any commencement, amendment, repeal or expiry affecting this republished law to 14 October 2015. The legislation history and amendment history of the republished law are set out in endnotes 3 and 4. Kinds of republications The Parliamentary Counsel’s Office prepares 2 kinds of republications of ACT laws (see the ACT legislation register at www.legislation.act.gov.au): authorised republications to which the Legislation Act 2001 applies unauthorised republications. The status of this republication appears on the bottom of each page. Editorial changes The Legislation Act 2001, part 11.3 authorises the Parliamentary Counsel to make editorial amendments and other changes of a formal nature when preparing a law for republication. Editorial changes do not change the effect of the law, but have effect as if they had been made by an Act commencing on the republication date (see Legislation Act 2001, s 115 and s 117). The changes are made if the Parliamentary Counsel considers they are desirable to bring the law into line, or more closely into line, with current legislative drafting practice. This republication does not include amendments made under part 11.3 (see endnote 1). -

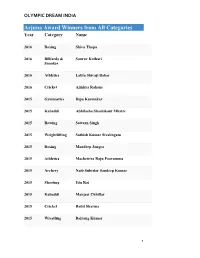

Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name

OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name 2016 Boxing Shiva Thapa 2016 Billiards & Sourav Kothari Snooker 2016 Athletics Lalita Shivaji Babar 2016 Cricket Ajinkya Rahane 2015 Gymnastics Dipa Karmakar 2015 Kabaddi Abhilasha Shashikant Mhatre 2015 Rowing Sawarn Singh 2015 Weightlifting Sathish Kumar Sivalingam 2015 Boxing Mandeep Jangra 2015 Athletics Machettira Raju Poovamma 2015 Archery Naib Subedar Sandeep Kumar 2015 Shooting Jitu Rai 2015 Kabaddi Manjeet Chhillar 2015 Cricket Rohit Sharma 2015 Wrestling Bajrang Kumar 1 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2015 Wrestling Babita Kumari 2015 Wushu Yumnam Sanathoi Devi 2015 Swimming Sharath M. Gayakwad (Paralympic Swimming) 2015 RollerSkating Anup Kumar Yama 2015 Badminton Kidambi Srikanth Nammalwar 2015 Hockey Parattu Raveendran Sreejesh 2014 Weightlifting Renubala Chanu 2014 Archery Abhishek Verma 2014 Athletics Tintu Luka 2014 Cricket Ravichandran Ashwin 2014 Kabaddi Mamta Pujari 2014 Shooting Heena Sidhu 2014 Rowing Saji Thomas 2014 Wrestling Sunil Kumar Rana 2014 Volleyball Tom Joseph 2014 Squash Anaka Alankamony 2014 Basketball Geetu Anna Jose 2 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2014 Badminton Valiyaveetil Diju 2013 Hockey Saba Anjum 2013 Golf Gaganjeet Bhullar 2013 Athletics Ranjith Maheshwari (Athlete) 2013 Cricket Virat Kohli 2013 Archery Chekrovolu Swuro 2013 Badminton Pusarla Venkata Sindhu 2013 Billiards & Rupesh Shah Snooker 2013 Boxing Kavita Chahal 2013 Chess Abhijeet Gupta 2013 Shooting Rajkumari Rathore 2013 Squash Joshna Chinappa 2013 Wrestling Neha Rathi 2013 Wrestling Dharmender Dalal 2013 Athletics Amit Kumar Saroha 2012 Wrestling Narsingh Yadav 2012 Cricket Yuvraj Singh 3 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2012 Swimming Sandeep Sejwal 2012 Billiards & Aditya S. Mehta Snooker 2012 Judo Yashpal Solanki 2012 Boxing Vikas Krishan 2012 Badminton Ashwini Ponnappa 2012 Polo Samir Suhag 2012 Badminton Parupalli Kashyap 2012 Hockey Sardar Singh 2012 Kabaddi Anup Kumar 2012 Wrestling Rajinder Kumar 2012 Wrestling Geeta Phogat 2012 Wushu M. -

Mahendra Singh Dhoni Exemplified the Small-Town Spirit and the Killer Instinct of Jharkhand by Ullekh NP

www.openthemagazine.com 50 31 AUGUST /2020 OPEN VOLUME 12 ISSUE 34 31 AUGUST 2020 CONTENTS 31 AUGUST 2020 7 8 9 14 16 18 LOCOMOTIF INDRAPRASTHA MUMBAI NOTEBOOK SOFT POWER WHISPERER OPEN ESSAY Who’s afraid of By Virendra Kapoor By Anil Dharker The Gandhi Purana By Jayanta Ghosal The tree of life Facebook? By Makarand R Paranjape By Srinivas Reddy By S Prasannarajan S E AG IM Y 22 THE LEGEND AND LEGACY OF TT E G MAHENDRA SINGH DHONI A cricket icon calls it a day By Lhendup G Bhutia 30 A WORKING CLASS HERO He smiled as he killed by Tunku Varadarajan 32 CAPTAIN INDIA It is the second most important job in the country and only the few able to withstand 22 its pressures leave a legacy By Madhavankutty Pillai 36 DHONI CHIC The cricket story began in Ranchi but the cultural phenomenon became pan-Indian By Kaveree Bamzai 40 THE PASSION OF THE BOY FROM RANCHI Mahendra Singh Dhoni exemplified the small-town spirit and the killer instinct of Jharkhand By Ullekh NP 44 44 The Man and the Mission The new J&K Lt Governor Manoj Sinha’s first task is to reach out and regain public confidence 48 By Amita Shah 48 Letter from Washington A Devi in the Oval? By James Astill 54 58 64 66 EKTA KAPOOR 2.0 IMPERIAL INHERITANCE STAGE TO PAGE NOT PEOPLE LIKE US Her once venerated domestic Has the empire been the default model On its 60th anniversary, Bangalore Little Streaming blockbusters goddesses and happy homes are no for global governance? Theatre produces a collection of all its By Rajeev Masand longer picture-perfect By Zareer Masani plays performed over the decades By Kaveree Bamzai By Parshathy J Nath Cover photograph Rohit Chawla 4 31 AUGUST 2020 OPEN MAIL [email protected] EDITOR S Prasannarajan LETTER OF THE WEEK MANAGING EDITOR PR Ramesh C EXECUTIVE EDITOR Ullekh NP Congratulations and thanks to Open for such a wide EDITOR-AT-LARGE Siddharth Singh DEPUTY EDITORS Madhavankutty Pillai range of brilliant writing in its Freedom Issue (August (Mumbai Bureau Chief), 24th, 2020). -

TIARA Research Final-Online

TIARAResearch Insight Based Research Across Celebrities Indian Institute of Human Brands 2020 About IIHBThe Indian Institute of Human Brands (IIHB) has been set up by Dr. Sandeep Goyal, India’s best known expert in the domain of celebrity studies. Dr. Goyal is a PhD from FMS-Delhi and has been researching celebrities as human brands since 2003. IIHB has many well known academicians and researchers on its advisory board ADVISORY Board D. Nandkishore Prof. ML Singla Former Global Executive Board Former Dean Member - Nestlé S.A., Switzerland FMS Delhi Dr. Sandeep Goyal Chief Mentor Dr. Goyal is former President of Rediffusion, ex-Group CEO B. Narayanaswamy Prof. Siddhartha Singh of Zee Telefilms and was Founder Former Managing Director Associate Professor of Marketing Chairman of Dentsu India IPSOS and Former Senior Associate Dean, ISB 0 1 WHY THIS STUDY? Till 20 years ago, use of a celebrity in advertising was pretty rare, and quite much the exception Until Kaun Banega Crorepati (KBC) happened almost 20 years ago, top Bollywood stars would keep their distance from television and advertising In the first decade of this century though use of famous faces both in advertising as well as in content creation increased considerably In the last 10 years, the use of celebrities in communication has increased exponentially Today almost 500 brands, , big and small, national and regional, use celebrities to endorse their offerings 0 2 WHAT THIS STUDY PROVIDES? Despite the exponential proliferation of celebrity usage in advertising and content, WHY there is no organised body of knowledge on these superstars that can help: BEST FIT APPROPRIATE OR BEST FIT SELECTION COMPETITIVE CHOOSE BETTER BETWEEN BEST FITS PERCEPTION CHOOSE BASIS BRAND ATTRIBUTES TRENDY LOOK AT EMERGING CHOICES FOR THE FUTURE 0 3 COVERAGE WHAT 23 CITIES METRO MINI METRO LARGE CITIES Delhi Ahmedabad Nagpur (incl. -

Cobbling Together the Dream Indian Eleven

COBBLING TOGETHER THE DREAM INDIAN ELEVEN Whenever the five selectors, often dubbed as the five wise men with the onerous responsibility of cobbling together the best players comprising India’s test cricket team, sit together to pick the team they feel the heat of the country’s collective gaze resting on them. Choosing India’s cricket team is one of the most difficult tasks as the final squad is subjected to intense scrutiny by anybody and everybody. Generally the point veers round to questions such as why batsman A was not picked or bowler B was dropped from the team. That also makes it a very pleasurable hobby for followers of the game who have their own views as to who should make the final 15 or 16 when the team is preparing to leave our shores on an away visit or gearing up to face an opposition on a tour of our country. Arm chair critics apart, sports writers find it an enjoyable professional duty when they sit down to select their own team as newspapers speculate on the composition of the squad pointing out why somebody should be in the team at the expense of another. The reports generally appear on the sports pages on the morning of the team selection. This has been a hobby with this writer for over four decades now and once the team is announced, you are either vindicated or amused. And when the player, who was not in your frame goes on to play a stellar role for the country, you inwardly congratulate the selectors for their foresight and knowledge. -

Corporate Centre, Mumbai on 6Th January 06

TRANSFORMING WITH PASSION Jeeef<e&keâ efjheesš& Annual Report 2005-06 CMD, Dr. Anil K. Khandelwal welcoming Rahul Dravid, Brand Hon’ble Finance Minister Mr. P. Chidambaram addressing the Ambassador of the Bank on 6th June 05 – Logo launch day. Board of Directors at Corporate Centre, Mumbai on 6th January 06. Hon'ble Finance Minister Mr. P. Chidambaram inaugurating new customer centric initiatives at Corporate Centre, Mumbai on 6th January 06. Mr. Vinod Rai, Director, inaugurating the state-of-the-art Mr. Keith Vaz, MP, Leicester East, inaugurating Bank's 8th branch in Data Centre of the Bank in Mumbai on 10th December 05. U.K. on 3rd August 05 with CMD, Dr. Anil K. Khandelwal & Baroness Usha Prashar of Runnymede CBE, the Guest of Honour. efJe<eÙe metÛeer Contents Jeeef<e&keâ efjheesš& Annual Report 2005-06 he=‰ DeOÙe#eerÙe JekeäleJÙe................................ 24 efveosMekeâeW keâer efjheesš& .............................. 26 «eeHeâ ............................................. 43 cenlJehetCe& efJeòeerÙe metÛekeâ.......................... 45 legueve-he$e ........................................ 48 ueeYe-neefve uesKee ................................. 49 vekeâoer-ØeJeen efJeJejCeer ............................ 81 uesKee hejer#ekeâeW keâer efjheesš& ........................ 83 mecesefkeâle efJeòeerÙe efJeJejefCeÙeeb ...................... 85 keâeheexjsš-efveÙeb$eCe................................ 113 veesefšme ......................................... 141 Page F&meerSme / Øee@keämeer Heâece& / GheefmLeefle heÛeea ........ 145 Chairman's -

Sep 2017 03:00PM

PROFESSIONAL EXAMINATION BOARD Police Constable Recruitment Test - 2017 10th Sep 2017 03:00PM Topic:- General Knowledge and Logical Knowledge 1) Who is the Union Minister for Railways? / रेलवे के के ीय मंी कौन ह? 1. Suresh Prabhu / सुरेश भु 2. Chaudhary Birender Singh / चौधरी बीरे िसंह 3. Thaawar Chand Gehlot / थावर चंद गहलोत 4. Piyush Goyal / पीयूष गोयल Correct Answer :- Suresh Prabhu / सुरेश भु 2) Who is the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission? / परमाणु ऊजा आयोग का अ कौन है? 1. Madhavan Nair / माधवन नायर 2. U R Rao / यु आर राव 3. Sekhar Basu / शेखर बसु 4. A S Kiran Kumar / ए एस िकरण कु मार Correct Answer :- Sekhar Basu / शेखर बसु 3) Today is Sunday. After 1344 days it will be: / आज रिववार है। 1344 िदनो ं के बाद यह िन न होगा: 1. Tuesday / मंगलवार 2. Monday / सोमवार 3. Saturday / शिनवार 4. Sunday / रिववार Correct Answer :- Sunday / रिववार 4) Which Schedule of the Constitution lists the languages recognized by it? / संिवधान की िकस अनुसूची म इसके ारा मा य भाषाएं सूचीब ह? 1. Sixth Schedule / छठी अनुसूची 2. Seventh Schedule / सातवी ं अनुसूची 3. Ninth Schedule / नवी ं अनुसूची 4. Eighth Schedule / आठवी ं अनुसूची Correct Answer :- Eighth Schedule / आठवी ं अनुसूची 5) The present defence minister of India is__________. / भारत के वतमान रा मंी __________ ह। 1. Manohar Parrikkar / मनोहर पारकर 2. -

India Eye Series-Saving Win Over Australia

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2019 (PAGE 14) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU India eye series-saving win over Australia Manu, Heena fizzle out in Men’s Cricket U-23 One Day Tournament BENGALURU, Feb 26: remains to be seen if Dhawan is unbeaten 29 off 37 balls as India J&K drubs TN by 5 wkts brought back into the side to open managed 126 for seven in Vizag. qualifications; Anish finishes 5th The focus remains firmly on alongside Rohit Sharma or the He was able to silence his crit- NEW DELHI, Feb 26: women's 10am air pistol ahead it became an uphill task for him via VJD Method the World Cup but India would team retains the opening combi- ics with a solid showing in of Taipei's Chia Ying Wu (238.4) from thereon. Excelsior Sports Correspondent and Abhishant Bakshi claimed also be desperate to ensure that a nation which featured in Vizag. Australia and New Zealand but Anish Bhanwala could not and Korean Bomi Kim (218.3). The 16-year-old survived a one wicket each. home series does not slip out of "Anything is possible now. We his rather slow innings on Sunday make up for Manu Bhaker and In the day's other event, the shoot-off with France's Clement JAMMU, Feb 26: All-round- In reply, J&K managed to their grip when they take on want to give game time to Rahul has got the tongues wagging Heena Sidhu's failure to reach women's 50m rifle positions, Bessaguet, but a 3 in the next er Abid Mushtaq and skipper score 181/5 in 37.2 overs in a Australia in the second and final and Pant to figure out what we again over his waning finishing the women's 10m air pistol final, India's Nityanadam was 36th series was not enough to keep Sahil Lotra slammed magnifi- rain-hit match and the match T20 International here on tomor- need to do in the World Cup," abilities. -

Manchester United Lose Patience, Sack Mourinho Tottenham Manager Mauricio AFP Who Played for United

Kohli plays down ‘banter’ as Aussies level series PAGE 16 WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 19, 2018 Lionel Messi collects a record 5th Golden EFL CUP Shoe award as top goalscorer in Europe ARSENAL VS TOTTENHAM Manchester United lose patience, sack Mourinho Tottenham manager Mauricio AFP who played for United. Tot- Pochettino. (REUTERS) MANCHESTER (UK) tenham Hotspur manager Mauricio Pochettino is also MANCHESTER UNITED strongly tipped. Pochettino sacked manager Jose Mour- Mourinho’s reign had start- inho on Tuesday after the ed well enough with the League fits bill as club’s worst start to a season Cup and the Europa League in nearly three decades. trophies but for a club that has new manager, Mourinho, 55, became in- been champions of England 20 creasingly spiky in his last few times, neighbours Manchester says Neville months at Old Trafford, lash- City’s dominance over them in ing out at the board’s transfer the league has hurt. AFP policy and turning his fire on The wound went even LONDON his squad, especially record deeper for Mourinho as City signing Paul Pogba. are managed by Pep Guardi- GARY NEVILLE says Man- His constant complaints ola, who got the better of him chester United should target about the players’ lack of de- when he was in charge at Bar- Mauricio Pochettino as their sire had an impact on the celona and Mourinho was at new manager after sacking pitch, culminating in the 3-1 Real Madrid. Jose Mourinho, describing the defeat by Premier League Despite his protestations Spurs boss as the “ideal candi- leaders Liverpool on Sunday to the contrary, the United date”. -

Androcentrism in Indian Sports

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Androcentrism in Indian sports Bijit Das [email protected] Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of Sociology Dibrugarh University Dibrugarh, Assam, India 786004 Abstract The personality of every individual concerning caste, creed, religion, gender in India depends on the structures of society. The society acts as a ladder in diffusing stereotypes from generation to generation which becomes a fundamental constructed ideal type for generalizing ideas on what is masculine or feminine. The gynocentric and androcentric division of labor in terms of work gives more potential for females in household works but not as the position of males. This paper is more concentrated on the biases of women in terms of sports and games which are male- dominated throughout the globe. The researcher looks at the growing stereotypes upon Indian sports as portrayed in various Indian cinemas. Content analysis is carried out on the movies Dangal and Chak de India to portray the prejudices shown by the Indian media. A total of five non-fictional sports movies are made in India in the name of Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013), Paan Singh Tomar(2012), MS Dhoni: An untold story(2016), Azhar(2016), Sachin: A billion dreams(26 May 2017) are on male sportsperson whereas only two movies are on women, namely Mary Kom (2014), Dangal(2017). This indicates that male preference is more than female in Indian media concerning any sports. The acquaintance of males in every sphere of life is being carried out from ancient to modern societies. This paper will widen the perspectives of not viewing society per media but to the independence and equity of both the sex in every sphere of life. -

Page10sports.Qxd (Page 1)

SUNDAY, APRIL 17, 2016 (PAGE 10) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU KKR post comprehensive win Upbeat Delhi Daredevils face India's grit not enough as stiff challenge from RCB over Sunrisers Hyderabad BENGALURU, Apr 16: but they will now be facing Australia clinch 9th Azlan title HYDERABAD, Apr 16: RCB, who have also notched IPOH (Malaysia), Apr 16: Azlan Shah Cup. For India, this obstructed on top of the circle, but Riding high after an was the second time they finished Harmanpreet Singh's shot posed Brilliant bowling by the pace up a comprehensive 45-run India suffered a 0-4 drubbing emphatic victory against win over Sunrisers with the silver medal in seven little threat as the custodian duo of Umesh Yadav and Morne Kings XI Punjab, a rejuvenat- at the hands of world champions final appearances. blocked it with his pads. Morkel, followed by skipper TODAY'S FIXTURE Australia to settle for a silver Playing to a plan at the begin- Craig increased Australia's Gautam Gambhir's superb half- Rising Pune Supergiants Vs Kings XI Punjab (Mohali) 4 PM medal, their best finish in six ning, India managed to keep the lead with an outstanding goal in century, powered Kolkata Royal Changers Bangalore Vs Delhi Daredevils (Bengaluru) 8 PM years, in the 25th Sultan Azlan Australians away from their the 35th minute when he dived to Knight Riders to a comprehen- Shah Cup hockey tournament citadel in the first quarter and deflect a cross from Blake Govers sive eight-wicket win over Hyderabad in their opening here today. ed Delhi Daredevils will aim game.