Final Evaluation of AWASAR Project CARE Nepal-NURTURE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Security Bulletin 29

Nepal Food Security Bulletin Issue 29, October 2010 The focus of this edition is on the Mid and Far Western Hill and Mountain region Situation summary Figure 1. Percentage of population food insecure* 26% This Food Security Bulletin covers the period July-September and is focused on the Mid and Far Western Hill and Mountain (MFWHM) 24% region (typically the most food insecure region of the country). 22% July – August is an agricultural lean period in Nepal and typically a season of increased food insecurity. In addition, flooding and 20% landslides caused by monsoon regularly block transportation routes and result in localised crop losses. 18 % During the 2010 monsoon 1,600 families were reportedly 16 % displaced due to flooding, the Karnali Highway and other trade 14 % routes were blocked by landslides and significant crop losses were Oct -Dec Jan-M ar Apr-Jun Jul-Sep Oct -Dec Jan-M ar Apr-Jun Jul-Sep reported in Kanchanpur, Dadeldhura, western Surkhet and south- 08 09 09 09 09 10 10 10 eastern Udayapur. NeKSAP District Food Security Networks in MFWHM districts Rural Nepal Mid-Far-Western Hills&Mountains identified 163 VDCs in 12 districts that are highly food insecure. Forty-four percent of the population in Humla and Bajura are reportedly facing a high level of food insecurity. Other districts with households that are facing a high level of food insecurity are Mugu, Kalikot, Rukum, Surkhet, Achham, Doti, Bajhang, Baitadi, Dadeldhura and Darchula. These households have both very limited food stocks and limited financial resources to purchase food. Most households are coping by reducing consumption, borrowing money or food and selling assets. -

Summer Paddy Crop Production Increased by 17%

Food Security Bulletin - 19 United Nations World Food Programme FS Bulletin, March 2008 Food Security Monitoring and Analysis System Issue 19 Key Findings 9 Nepal’s summer paddy crop production increased by 17%. 9 Initial reports indicate that the winter crop will yield substantially lower crops in the Mid and Far Western region, due to late winter rains. 9 Market Prices have increased significantly despite these good crop yields leaving an estimated 3.8 million extremely vulnerable. 9 Additionally, many areas in Mid- and Far-West suffered from poor paddy production and are facing increasing food insecurity. The outlook for the winter crop production in many of these areas is also worrying. 9 Many of the extreme poor households in flood affected areas are still struggling to cope with the longer-term affects of the flood. 9 Average household food stocks are down by half compared to a year ago. 9 More households are facing difficulties in accessing sufficient food. Coping strategies are more frequently adopted compared to last quarter and more households find it difficult to find employment. Editorial The past couple of months were the beginning of April. Preliminary Food Security Phase Classification characterized by ongoing bandhs in the expectations are presented on page 4 Map Terai, resulting in shortages of fuel and of this bulletin. other essential items and rising food With support from the SENAC project prices across Nepal. Price rises in In rural areas, the current food security (Strengthening Emergency Needs coarse rice were further exacerbated by situation is largely based upon Assessment Capacity within WFP), the the ongoing ban on export of non- production of the summer crops, maize methodology used to develop the basmati rice from India and the global and rice, as winter wheat has yet to be quarterly food security phase cereal price hikes (see WFP Market harvested. -

Download 4.06 MB

Environmental Compliance Monitoring Report Semi-Annual Report Project Number: 44214-024 Grant Number: 0357-NEP July 2020 Nepal: Building Climate Resilience of Watersheds in Mountain Eco-Regions Project Prepared by the Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank. This environmental Compliance Monitoring Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Government of Nepal Department of Forests and Soil Conservation Building Climate Resilience of Watersheds in Mountain Eco-Regions (BCRWME) Project (ADB Loan/Grant No.: GO357/0358-NEP) Semiannual Environemntal Monitoring Report of BCRWME Sub-projects (January to June 2020) Preparaed By BCRWME Project Project Management Unit Dadeldhura July, 2020 ABBREVIATION ADB : Asian Development Bank BCRWME : Building Climate Resilience of Watersheds in Mountain Eco- Regions BOQ : Bills of Quantity CDG : Community Development Group CFUG : Community Forest User Group CO : Community Organizer CPC : Consultation, Participation and Communications (Plan) CS : Construction Supervisor DDR : Due Diligence -

Sharing the Burden: Improving the Welfare of Nepal's Mountain Porters

Second Year Policy Analysis ` Sharing the Burden: Improving the Welfare of Nepal’s Mountain Porters Upasana Khadka and Boban Paul March 16th, 2015 SYPA Advisor: Professor Monica Singhal Section Leader: Professor Rema Hanna Written in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Public Administration in International Development, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University Acknowledgement We would like to thank our SYPA Advisor Professor Monica Singhal and Section Leader Professor Rema Hanna for their insightful feedback on our work, for constantly pushing us to think critically and for all the support and encouragement they provided at all stages of the SYPA process. They have been fantastic advisors and we are immensely grateful for the opportunity we got to work closely with them. We have many people to thank from Nepal. First and foremost, a special thank you to Mr. Ramesh Dhamala, President of the Trekking Agents Association of Nepal (TAAN), for his support throughout this process. His help in designing this project, the support he provided with the survey work and his enthusiasm and encouragement are greatly appreciated. Thank you to Mr. Yubraj Shrestha from the Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation who provided insightful feedback and support with data collection. Mr. Ratan Saud from NATHM deserves a special thank you for helping us collect data at the institute and the President of NATHM, Mr. Chuda Mani Sharma Kattel, provided invaluable feedback on our recommendations. We appreciate the support from Ramchandra Sedai, Hari Devkota and Rabi Jung Pandey and are especially grateful to Pemba Gyalje Sherpa for his inspiring stories from his Everest expeditions and his candid views on the situation of porters. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

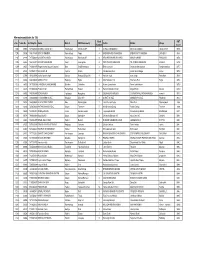

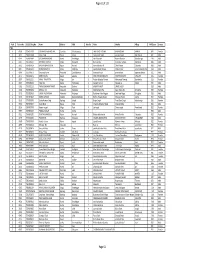

PMT Result 2075 List.Xlsx

Alternate candidates for TSLC Ward PMT S. No. Token No SLC Reg No Name District VDC/Municipality Father Mother Village Number Score 1205 29868 7477022010 BHARAT RAJ BHATT Kanchanpur Bhimdatta NP 8 SHREE NAND BHATT MOTI DEVI BHATT TILACHOUR 997.6 1206 30396 1807718001 BINUTA KHADKA Ramechhap Farpu 4 BADRI BAHADUR KHADKA BISHNU MAYA KHADKA LACHEPU 997.6 1207 32226 7277059022 SUSMITA CHAND Kanchanpur Bhimdatta NP 6 KESHAB BAHADUR CHAND MANJU CHAND BANGAUN 997.6 1208 34943 7441233012 SUSMITA ADHIKARI Kaski Lwangghale 4 TEK PRASAD ADHIKARI TIL KUMARI ADHIKARI KOLELI 997.6 1209 30035 7436031070 Ragani kumari jayswal Jayswal Bara GanjBhawanipur 3 Bhairo parsad Shambha devi jayswal Ganjbhawanipur 997.7 1210 32691 7457005127 SUJATA G M Pyuthan Khaira 2 Nim Bahadur G m Laxmi Gharti Magar Palasi 997.8 1211 32804 7010176010 aasha kumari singh Sunsari RamganjBelgachhi 8 hariram singh nanu singh Ramdhuni 997.8 1212 33666 6946100001 ANDIKA PUN Baglung Righa 6 Man Bahadur Pun Tilachana Pun Righa 997.8 1213 34050 7417059004 CHANDIKA LAMICHHANE Dolakha Chilankha 8 Kumar Lamichhane Rama Lamichhane 997.8 1214 32273 7418082005 Prabin Khatri Ramechhap Deurali 6 Ganesh Bahadur Khatri Maiya Khatri Deurali 997.9 1215 33092 7401013060 SONI MADEN Taplejung Hangdeva 9 SILBAHADUR MADEN SITAMAYA PALUNGWA MADEN eseratol 997.9 1216 33391 7225022009 CHHOISANG GHALE Nuwakot Bidur N.P. 8 SHAKTI GHALE MANMAYA GHALE RAISING 997.9 1217 28738 7436099042 AJAY KUMAR YADAV Bara Madhurijabdi 7 Jhoti Prasad Yadav Mina Devi Madhurijabdi 998 1218 30814 7456070039 PATHA BAHADUR D.C. -

Danphe Newsletter

1 Bird Conservation Nepal QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER VOLUME 26 BULLETIN 2 JUNE 2017 Review on Distribution of Cheer Pheasant Catreus wallichii in Nepal 1Hari Basnet and 2Laxman Prasad Poudyal Introduction restricted within a narrow belt from northeast Pakistan, through northern India to the Kaligandaki Valley in Western Nepal (Delacour Cheer Pheasant Catreus wallichii is a relict, monotypic species of 1977, Ali & Ripley 1998). The Cheer Pheasant’s small population the genus Catreus (Del Hoyo et al. 1994) and order Galliformes. is naturally fragmented as it lives in successional habitats that are It is an endemic species of the Himalayas (Grimmett et al. 1998) patchy in distribution. The global population of Cheer is estimated Cheer Pheasant by Hari Basnet 2 BIRD CONSERVATION NEPAL - NEWSLETTER to be 2,000-2,700 mature individuals (BirdLife International 2017) whilst the Nepal population is estimated to be less than 1,000 birds (Inskipp et al. 2016). This species is categorized as Tune in to Vulnerable (IUCN 2016), included under Appendix I of CITES and is one of nine protected birds of Nepal listed in the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 2029 (NPWC 1973). It has been recently assessed as Endangered (based on the criteria A2acd and C2a (I)) (Inskipp et al. 2016) in Nepal. Cheer favours open A Radio Program byby forest with some grass cover and rocky crags, very precipitous Bird Conservation NNepalepal terrain with scrub, tall grasses and stunted trees, and craggy hillsides supporting scrub and stunted trees (Singh et al. 2011). It Radio Sagarmatha 102.42.4 breeds during the spring season (late April-early June) (Ali & Ripley Lalitpur (Saturday 7:4508:00)00) 1983) when it gives sporadic and irregular calls throughout the day, but especially at dawn. -

Pray for Nepal

Pray for Nepal Bajhang Bajura Doti Achham Kailali Seti, Bajura Greetings in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, Thank-You for committing to join with us to pray for the well-being of every village in our wonderful country. Jesus modeled his love for every village when he was going from one city and village to another with his disciples. Next, Jesus would mentor his disciples to do the same by sending them out to all the villages. Later, he would monitor the work of the disciples and the 70 as they were sent out two-by-two to all the villages. (Luke 8-10) But, how can we pray for the 3,984 VDCs in our Country? In the time of Nehemiah, his brother brought him news that the walls of Jerusalem were torn down. The wall represented protection, safety, blessing, and a future. Nehemiah prayed, fasted, and repented for the sins of the people. God answered Nehemiah’s prayers. The huge task to re-build the walls became possible through God’s blessings, each person building in front of their own houses, and the builders continuing even in the face of great persecution. For us, each village is like a brick in the wall. Let us pray for every village so that there are no holes in the wall. Each person praying for the villages in their respective areas would ensure a systematic approach so that all the villages of the state would be covered in prayer. Some have asked, “How do you eat an Elephant?” (How do you work on a giant project?) Others have answered, “One bite at a time.” (One step at a time - in small pieces). -

Decentralized Rural Infrastructure and Livelihoods Project

Environmental Assessment Report Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 30232 January 2008 NEP: Decentralized Rural Infrastructure and Livelihoods Project Prepared by [Author(s)] [Firm] [City, Country] Prepared by District Development Committee, Mugu for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). Prepared for [Executing Agency] [Implementing Agency] The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s The initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................................................................................IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (NEPALI)…………………………………………………………………....VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................................IX SALIENT FEATURES............................................................................................................................... XII 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 BACKGROUND: ....................................................................................................................................................1 -

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

Service Contract to Conduct an End-Line Survey in Mugu UNICEF Nepal Country Office (NCO)

Service contract to conduct an end-line survey in Mugu UNICEF Nepal Country Office (NCO) 1. BACKGROUND AND JUSTIFICATION Child mortality in Nepal has decreased over the years. Death among children under five per 1,000 live births fell from 91 in 2001 to 39 in 2016.1,2 Neonatal deaths, death during the first 28 days of life per 1,000 live births, also decreased from 39 in 2001 to 21 in 2016.3,4 It shows that there is little progress in reduction of neonatal deaths. Further, over half of all children under five deaths occur in the first month of life, indicating the importance of strengthening maternal and newborn health programme to contribute to Nepal Health Sector Strategy and Sustainable Development Goal ‘3: Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages.’ Still many children and newborn babies face challenges in Karnali Province. Geographical characteristics in mountainous areas make access to health services difficult especially for women and children. Under five mortality and neonatal mortality in Karnali Province was 58 and 29, respectively, 5,6 which are much higher than the national average. Karnali Province also has the lowest percentage of institutional deliveries (36% in Karnali vs. 57% national) and the highest prevalence of stunting among young children (55% in Karnali vs. 36% national). In the country programme (2018-2022), UNICEF strives to improve the access and quality of maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health (MNCAH) services particularly in the most marginalized and deprived areas. In this effort, UNICEF has implemented comprehensive interventions to strengthen local governance, infrastructure and quality of health service at health facility levels and to promote healthy behaviour among caregivers, families and communities. -

Notice Fifth Lot for All PMT Upto 2075.10.13 Selected & Alternate 2Nd Quintile

मत / / गतेको "गोरखाप दैनक "मा काशत सुचना अनुसार ावधक श ालयहमा डलोमा तहमा भनाx भएर वगत (चार पटक ) मा परयोजनाले सुचना काशन गदाx तो"कएको #यादभ$ आवेदन दताx गराउन छु टेका व(याथ*हले छा$वि-तृ आवेदन (Scholarship Application) फाराम परयोजनाको वेवसाइट www.event.gov.np बाट डाउनलोड गर2 भरेर श ालयले मा3णत गर2 प"रयोजना स%चवालय , वु'नगरमा मत /( /() काया* य समयभ दताx गराउनुहोला । सो5ह सुचना अनुसार डलोमा तहमा बाँक8 रहेका 99 कोटामा छा$वि-तमाृ छनोट गन: योजनका लाग पुवx काशन भएको पएमट2 यो;यता<म अनुसारको =>?@ जनाको नामावल2 । नोट : आवेदन फाराम प"रयोजनाका पुवx सुचनाह1 अनुसार दताx ग"रसकेका 2व3याथ5ह1ले भनु x नपन6 । Selected candidates for Diploma Ward Token VDC/Municipa PMT SN. SLC Reg No Name District Numb Father Mother Village No lity Score er 1 34871 7416018187 SRIJANA KUMARI MAHATO Siraha RamnagarMirchaiya 7 BINDESHWAR MAHATO SUDI RAM DULARI DEVI BAN KARYALAYA CHOWK884.5 2 28644 7259004015 DANSINGH ROKAYA Humla ShreeNagar 5 Barkhe Rokaya Gorikala Parki Rokaya Village 899 3 28719 7059004006 BANDANA PHADERA Humla ShreeNagar 4 Netra Phadera Pushi Phadera Phadera Gaun 905 4 32936 7224003027 JEEWAN KUMAR NEUPANE Rasuwa Dhaibung 4 Khem Raj Neupane Chet Kumari Neupane Katunje 907.5 5 32696 7063022017 KAMAL ROKAYA Jumla Lihi(Rara) 6 MAN BAHADUR ROKAYA MANMA ROKAYA LIHI 910 6 32817 7124013003 Ghyu Jyalmo Tamang Rasuwa Gatlang 8 Kawa Tamang Dawa Chamo Tamang Gre 910.5 7 29380 6562005014 Dipak Kumar Shahi Kalikot Jubika 6 Harsa Bahadur Shahi Padma Shahi Jubitha 911.7 8 30311 7372001067 DEEPA PARIYAR Doti Dipayal Silgadhi N.P.5 DILIP PARIYAR NIRMALA PARIYAR SILGADI 915.5