Recent Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scott Miskimon, Partner Smith Anderson Buyer Beware Determining Liability When the Deal Falls Apart by Scott A

The following article was published in the October 2011 edition of the NCBA’s Real Property Law Section Newsletter. Author: Scott Miskimon, Partner Smith Anderson Buyer Beware Determining Liability When the Deal Falls Apart By Scott A. Miskimon Closing is months away and the buyer asks for a fourth extension The Seller Seeks a Closing of the closing date. The seller throws up his hands at the buyer’s end- less delays and indecision, and under a mistaken belief that the third The seller had long been dealing with a buyer who was unready extension of the closing date has expired, faxes a letter demanding a or indecisive, and who would soon prove inconsistent. Moreover, closing now or the deal is off. Should the buyer’s closing attorney step by mistake the seller believed that June 1, 2007 – rather than July 31, in and try to coax the seller to close? Or should the buyer immedi- 2007 – was the buyer’s deadline to close. In actuality, June 1 was the ately file suit? And what should the seller’s attorney do, particularly end of the buyer’s due diligence period. Under this mistaken belief if in the meantime the seller agrees to sell the land to someone else? as to the closing date, the seller faxed a letter to the buyer’s broker to North Carolina’s appellate courts recently decided the case of Pro- prod the buyer to close. In this letter, the seller’s president noted his file Investments No. 25, LLC v. Ammons East Corporation, 2010 understanding of the deadline for closing, expressed his frustration N.C. -

Damages: the Measure of Damages for Anticipatory Repudiation and Seller's Duty to Mitigate, 37 Marq

Marquette Law Review Volume 37 Article 8 Issue 1 Summer 1953 Damages: The eM asure of Damages for Anticipatory Repudiation and Seller's Duty to Mitigate Fintan M. Flanagan Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Fintan M. Flanagan, Damages: The Measure of Damages for Anticipatory Repudiation and Seller's Duty to Mitigate, 37 Marq. L. Rev. 76 (1953). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol37/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW [Vol. 37 York rule when inter vivos disposition is restricted. Although in the Michel case the contract was binding prior to death and the stock was held to have passed under the will, the court stressed that this was because of the fact situation there, the optionee being also made legatee of the shares. Regardless of the merits of this decision when considered in the light of the Wilson case 21 it seems safe to predict that at least where that peculiar fact situation does not exist, the court would prob- ably adopt the New York or so-called "Federal Rule." Thus until further decisions clarify the present situation, it would seem most advisable for the attorney in drafting one of these agree- ments to fix its provisions with an eye to making the price set acceptable to the Commissioner of Internal Revenue and probably the Wisconsin Tax Department will follow suit unless the option holder is bequeathed the shares. -

Contracts Outline

Contracts Outline NYU Fall 2004, Professor Barry Friedman Chapter 1 What Promise Ought We Enforce.............................................................. 8 1. Why we enforce promise......................................................................................... 8 1.1. Moral claim (Foundational) ........................................................................ 8 1.2. Efficiency / Mutual exchange: we can not exchange things simultaneously.............................................................................................. 8 1.3. Reliance: somebody relies on the promise and changes his plan............. 8 1.4. Will theory: somebody makes the promise means he wants the promise to be enforced. .............................................................................................. 8 1.5. Benefits unjustly retained............................................................................ 8 2. Promise with good consideration........................................................................... 8 2.1. Bargain for exchange is the test of good consideration ............................ 8 2.2. Past consideration is no good consideration.............................................. 9 2.3. Moral promise could be enforced under material benefit rule................ 9 2.4. Illusory promise is no good consideration ................................................. 9 2.5. Conditional promise could be good consideration.................................. 10 2.6. Good consideration could be implied...................................................... -

The Impact of Article 2 of the U.C.C. on the Doctrine of Anticipatory Repudiation, 9 B.C.L

Boston College Law Review Volume 9 Article 3 Issue 4 Number 4 7-1-1968 The mpI act of Article 2 of the U.C.C. on the Doctrine of Anticipatory Repudiation E Hunter Taylor Jr Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Commercial Law Commons Recommended Citation E H. Taylor Jr, The Impact of Article 2 of the U.C.C. on the Doctrine of Anticipatory Repudiation, 9 B.C.L. Rev. 917 (1968), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol9/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. E IMAC O AICE 2 O E U.C.C. O E OCIE O AICIAOY EUIAIO E. UE AYO, . * In AnlArn l, ntrt nrll vd pr r r f pr pprtd b ffnt ndrtn t rndr th pr r pr lll bltr. Whn ntrt nt prfrd rdn t t tr t d t hv bn brhd, nd th l rr th brhn prt t nr n d. In rtn, prr ndr ntrt nt t th pr h ntnt nt t prfr h bltn t th t t ll b lld fr b th ntrt. Sh ntn trd "ntptr rpdtn" f th ntrt. Whn n ntptr r pdtn r, th tn rd hthr th pr h n dt l fr brh f th ntrt. -

C:\Temp\Notes6030c8\Menottimtd Anticipatory Repudiation Claim.Wpd

Case 1:08-cv-02767 Document 50 Filed 04/20/2009 Page 1 of 7 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION RALPH MENOTTI, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) No. 08 C 2767 ) THE METROPOLITAN LIFE INSURANCE ) Judge Nan R. Nolan COMPANY, ) ) Defendant. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Plaintiff Ralph Menotti has filed a three-count complaint against Metropolitan Life Insurance Company (“MetLife”) seeking to recover benefits allegedly owed to him under a disability insurance policy. The parties have consented to the jurisdiction of the United States Magistrate Judge pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 636(c), and MetLife now moves to dismiss Count II of the complaint for failure to state a claim. FED. R. CIV. P. 12(b)(6). For the reasons set forth below, the motion is granted. BACKGROUND1 MetLife, a New York corporation with its principal place of business in New York, New York, is an insurance company providing disability insurance. Menotti is a resident of Vernon Hills, Illinois who worked as a commodities broker, performing open outcry trading with the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (“CME”). (SAC ¶¶ 2, 3, 7.)2 On January 15, 1992, Menotti procured a disability insurance policy (the “Policy”) through New England Mutual Life Insurance Company, which is now part of MetLife. The Policy defines “Total Disability” to mean: (1) “You are unable to perform the important duties of Your Occupation; and (2) You are not engaged in any other gainful occupation; 1 In reviewing this motion to dismiss, the court accepts all well-pleaded factual allegations in the complaint. Richards v. Kiernan, 461 F.3d 880, 882 (7th Cir. -

MBE Subject Matter Outline: Contracts

MBE Subject Matter Outline: Contracts Contracts NOTE: Examinees are to assume that the Official Text of Articles 1 and 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code has been adopted and is applicable when appropriate. Approximately half of the Contracts questions on the MBE will be based on categories I and IV, and approximately half will be based on the remaining categories—II, III, V, and VI. Approximately one-fourth of the Contracts questions on the MBE will be based on the Official Text of the Uniform Commercial Code, Articles 1 and 2. MBE Subject Matter Outline: Contracts I. Formation of Contracts A. Mutual Assent 1. Offer & Acceptance 2. Unilateral, Bilateral, & Implied-in-fact Contracts B. Indefiniteness & absence of terms C. Consideration 1. Bargained-for exchange D. Obligations enforceable without bargained-for exchange 1. Reliance 2. Restitution E. Modification to Contracts MBE Subject Matter Outline: Contracts II. Defenses to Enforceability A. Incapacity to contract B. Duress & undue influence C. Mistake & misunderstanding D. Fraud, misrepresentation, & nondisclosure E. Illegality, unconscionability, and public policy F. Statute of frauds MBE Subject Matter Outline: Contracts III. Contract Content & Meaning A. Parole evidence B. Interpretation C. Omitted & implied terms MBE Subject Matter Outline: Contracts IV. Performance, Breach, & Discharge A. Conditions 1. Express 2. Constructive B. Excuse of conditions C. Breach 1. Material & partial breach 2. Anticipatory repudiation D. Obligations of good faith & fair dealing E. Express & implied warranties in sale-of-goods contracts IV.Performance, Breach, & Discharge (Cont.) F. Other performance matters 1. Cure 2. Identification 3. Notice 4. Risk of Loss G. Impossibility, impracticability, & frustration of purpose H. -

Anticipatory Repudiation of Contracts Herbert R

Cornell Law Review Volume 10 Article 2 Issue 2 February 1925 Anticipatory Repudiation of Contracts Herbert R. Limburg Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Herbert R. Limburg, Anticipatory Repudiation of Contracts, 10 Cornell L. Rev. 135 (1925) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol10/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Anticipatory Repudiation of Contracts HERBERT R. LnIBuRGt No branch of commercial law presents greater difficulties to the practitioner than the determination of the rights and obligations of the parties where a contract has been repudiated before its time for performance has arrived. There is no lack of literature upon the subject.' The law books are full of cases treating it in its various aspects. But the practitioner is bewildered by the apparent lack of unanimity in decision and comment. Not only do various jurisdictions reach wholly divergent results, but frequently the decisions in the same jurisdiction are difficult, if not impossible, to reconcile; and, when the perplexed student turns to the leading text writers for help, he will find that the fundamental doctrine of anticipatory repudiation, permitting an immediate suit for damages, is assailed by Prof. Williston as illogical and unsound while Prof. Ballantine takes direct issue with Prof. -

CONTRACTS October 2007 Question 3

FYLSX CONTRACTS October 2007 Question 3 Apple orchards ("Appre"), a grower of appres, entered into a written contract with Best Bakery ("Bakery") to supply Bakery with all of Bakery,s apple requirements for one year. Under the contract, Apple was required to deriver on the iirst dav of each month the quantity of appres that Bakery required. The contract price was $5,000 per month, payable upon detivery of eich shipment. Apple delivered the required quantity each month for the first six months. At the end of the sixth month, Apple assigned its contract with Bakery to FruitCo, which undertook to deliver the requisite quantities for the remainder of the contract term Bakery, having some doubts about FruitCo,s reliability, wrote both Apple'tirat and Fruitco a letter in which Bakery stated, "l want to be absolutely sure both Apple and Fruitco wirr guarantee that I receive the quantity of appres that I reeuire each month." Neither Apple nor FruitCo responded to Bakery's letter. In the seventh and eighth months of the contract, Fruitco made deliveries that were substantiallv short of the quantity that Bakery required and that Apple had previously delivered. Nevertheless, Bakery accepted and paid for the short shipments. At the end of the eighth month, Bakery entered into a contract with Davis Farms ("Davis") !o supply Bakery with its requirements for apples for the remaining four months of the year. The contract price was $7,500 per month, payablelpon delivery of each shipment. Bakery wrote a letter to Apple and Fruitco informing them that Bakery would no longer accept any apple shipments from either oi them. -

Contracts and Sales

Contracts and Sales MBE Testing Distribution MBE Question Breakdown ________ (I) Formation, (II) Consideration, (VII) Formation of Contracts: ________ Conditions, (IX) Impossibility, and (X) Consideration: ________ Discharge: Third-Party Beneficiary Contracts: ________ (III) Third-Party Beneficiaries, (IV) ________ Assignment and Delegation, (V) Statute Assignment and Delegation: ________ of Frauds, (IV) Parole Evidence, (VIII) Statute of Frauds ________ Remedies Parol Evidence and Interpretation ________ Conditions ________ Remedies ________ Impossibility, Impracticability, and ________ Frustration of Purpose Discharge of Contractual Duties ________ I. Formation of Contracts III. Third-Party Beneficiary Contracts A. Mutual Assent __ A. Intended Beneficiaries __ 1. Offer B. Incidental Beneficiaries __ 2. Acceptance C. Impairment or Extinguishment of Third- 3. Non-Conforming Acceptance Party Rights __ 4. Avoidance of Contract D. Enforcement by the Promisee __ B. Capacity to Contract __ IV. Assignment and Delegation C. Improper Contracts __ A. Assignment of Rights __ D. Implied-in-Fact Contracts and Quasi- Contracts __ B. Delegation of Duties __ E. Pre-Contract Detrimental Reliance __ V. Statue of Frauds F. Warranties __ A. Common Law __ II. Consideration B. Writing Requirement __ A. Bargained-for Exchange and Legal C. UCC __ Detriment __ VI. Parol Evidence and Interpretation B. Adequacy of Consideration __ A. Four Corners Rule __ C. Modern Substitutes for Bargain __ B. Collateral Contract Rule __ D. Modification of Contracts __ C. Evidence of Usage of Trade __ E. Compromise and Settlement of Claims D. Course of Dealing __ __ 1 VII. Conditions IX. Impossibility, Impracticability and A. Express Conditions __ Frustration of Purpose B. Constructive Conditions __ A. -

Monday September 22, 2014 Iowa Contracts

2014 Basic Skills Course Presented by the Iowa Bar Review School and The Iowa State Bar Association. Monday September 22, 2014 Iowa Contracts Law 4:15 p.m. - 5:15 p.m. Materials by Justice Edward Mansfield Iowa Supreme Court Judicial Branch Building 1111 East Court Avenue Des Moines, IA 50319 IOWA BASIC SKILLS June 2014 CONTRACTS BACK TO BASICS RECENT CASE SUMMARY Justice Michael Streit (with additional updates by Justice Edward Mansfield) 1 Disclaimer: This material does not reflect the views of the Iowa Supreme Court and should not be cited in a court proceeding. 2 BACK TO BASICS Recent Iowa Supreme Court cases demonstrate the importance of returning to basic contract principles when confronted with a contract case. Contract law in Iowa is pretty similar to what you learned in law school. I. IS THERE A CONTRACT? You have to have offer and acceptance (what we now call mutual manifestation of assent) and consideration (a bargained- for exchange). You also have to have sufficiently definite terms. a. There must be an offer. i. Blackford v. Prairie Meadows Racetrack and Casino Inc., 778 N.W.2d 184 (Iowa 2010). Facts: Individual was banned after he struck a slot machine and broke the machine’s glass belly. He continued to frequent the casino and later won $9,387. The casino refused to pay. The gambler argued the ban had been lifted, but a jury found he was still banned from the casino when he won the money. The parties focused on whether the casino had the authority to withhold winnings. -

Page 1 of 3 N.C.P.I.–Civil 502.05 CONTRACTS-ISSUE of BREACH by REPUDIATION

Page 1 of 3 N.C.P.I.–Civil 502.05 CONTRACTS-ISSUE OF BREACH BY REPUDIATION. GENERAL CIVIL VOLUME REPLACEMENT JUNE 2018 ------------------------------ 502.05 CONTRACTS – ISSUE OF BREACH BY REPUDIATION. The (state number) issue reads: “Did the defendant breach the contract by repudiation?”1 (You will answer this issue only if you have answered the (state number)2 issue “Yes” in favor of the plaintiff.) On this issue the burden of proof is on the plaintiff. This means that the plaintiff must prove, by the greater weight of the evidence, two things: First, that before the time arrived for the defendant to perform, the defendant repudiated [his entire obligation3] [a term going to the whole value of what the defendant was to perform] under the contract.4 A party to a contract repudiates5 his obligation when he expresses, by words or conduct,6 a positive, distinct, unequivocal and absolute [refusal] [inability] to perform. Second, that at the time of the defendant's repudiation, the plaintiff was ready, willing and able to perform his obligations as agreed and would have done so but for the repudiation by the defendant.7 NOTE WELL: If the plaintiff has already fully performed his obligations under the contract, modify the instruction to read, “At the time of the defendant’s repudiation, the plaintiff had performed his obligations as agreed.” 8 But note: In cases of partial performance, “the effect of breach by anticipatory repudiation is to relieve the non-repudiating party from further performance under the contract.” 9 Finally, as to the (state number) issue on which the plaintiff has the burden of proof, if you find by the greater weight of the evidence that the defendant breached the contract by repudiation, then it would be your duty to answer this issue “Yes” in favor of the plaintiff. -

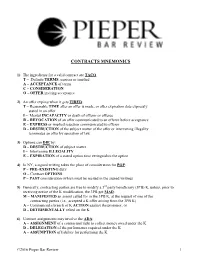

Contracts Mnemonics

CONTRACTS MNEMONICS 1) The ingredients for a valid contract are TACO: T – Definite TERMS, express or implied A – ACCEPTANCE of terms C – CONSIDERATION O – OFFER inviting acceptance 2) An offer expires when it gets TIRED: T – Reasonable TIME after an offer is made, or after expiration date expressly stated in an offer I – Mental INCAPACITY or death of offeror or offeree R – REVOCATION of an offer communicated to an offeree before acceptance E – EXPRESS or implied rejection communicated to offeror D – DESTRUCTION of the subject matter of the offer or intervening illegality terminates an offer by operation of law 3) Options can DIE by: D – DESTRUCTION of subject matter I – Intervening ILLEGALITY E – EXPIRATION of a stated option time extinguishes the option 4) In NY, a signed writing takes the place of consideration for POP: P – PRE–EXISTING duty O – Contract OPTIONS P – PAST consideration (which must be recited in the signed writing) 5) Generally, contracting parties are free to modify a 3rd party beneficiary (3PB) K, unless, prior to receiving notice of the K modification, the 3PB got MAD: M – MANIFESTED an assent called for in the 3PB K, at the request of one of the contracting parties (i.e., accepted a K offer arising from the 3PB K) A – Commenced a breach of K ACTION against the promisor, or D – DETRIMENTALLY relied on the K 6) Contract assignments may involve the ADA: A – ASSIGNMENT of a contractual right to collect money owed under the K D – DELEGATION of the performance required under the K A – ASSUMPTION of liability for performing