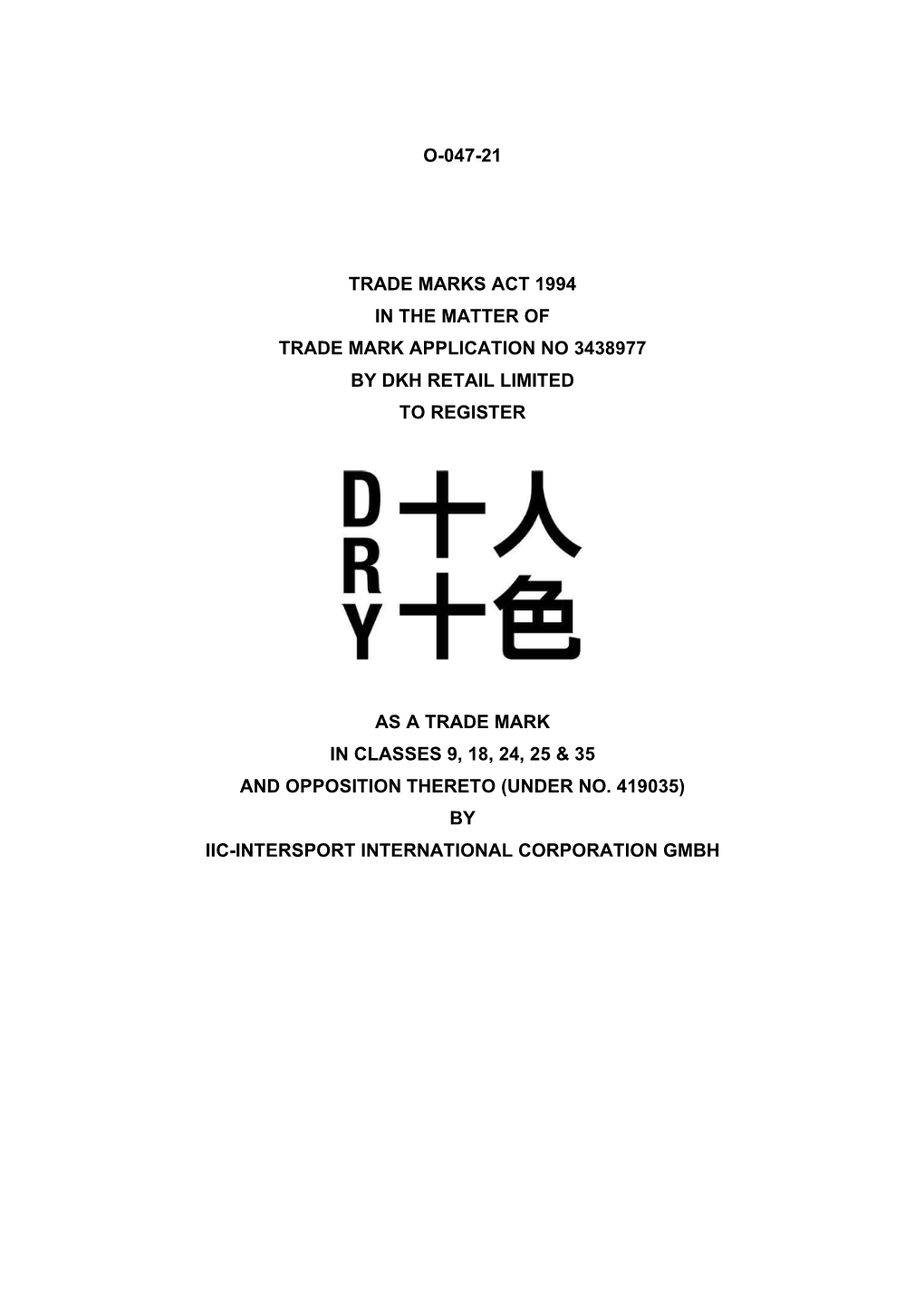

O/047/21 387Kb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Livingston County Guide To

LIVINGSTON COUNTY GUIDE TO RE-USE RE-DUCE RE-CYCLE & SAFE DISPOSAL This guide was developed to assist residents and businesses of Livingston County dispose of unwanted items in an environmentally friendly manner. This guide was designed for informational purposes only. This guide is not an endorsement of the businesses mentioned herein. It is a good practice to always call first to confirm the business or organizations’ services. Livingston County Solid Waste Program 2300 E. Grand River, Suite 105 Howell, MI 48843-7581 Phone: 517-545-9609 www.livgov.com/dpw E-mail: [email protected] Revised 2-2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page/s AMMUNITION & EXPLOSIVES 3 APPLIANCES & LARGE ITEM DISPOSAL 3 ARTS & CRAFTS SUPPLIES (including recycling Christmas lights) 4 ASBESTOS 4 AUDIO – See: CDs, Disks, Video Tapes, Albums, Records 4 AUTOMOBILES 5 AUTOMOTIVE FLUIDS 6 BATTERIES – All types (and locations of the drop-off buckets) 7, 8 BUILDING MATERIALS & CONSTRUCTION DEBRIS 7 CDs – Disks, Tapes, Video Tapes, Albums, Records & DVDs 9 CELLULAR PHONES 9 CLOTHING & SHOES 9 COMPUTERS & ELECTRONICS 10 DUMPS (See Landfills) 10 EYEGLASSES & HEARING AIDS 10 FIRE EXTINGUISHERS 10 FLUORESCENT BULBS AND TUBES 10 FOOD ITEMS 11 FURNITURE AND LARGE ITEMS – Donation or Disposal 11 HOUSEHOLD HAZARDOUS WASTE 11 LANDFILLS, DUMPS AND TRANSFER STATIONS 12 LAWN & GARDEN EQUIPMENT 12 MERCURY – Thermometers, Thermostats 12,18 METAL 13 NEWSPAPER 13 OFFICE SUPPLIES AND EQUIPMENT 13 PACKAGING or SHIPPING MATERIALS 14 PAINT – Latex & Oil-Based Paints 14 PAPER SHREDDING-Check with your Townships and/or Recycle Livingston (pg. 16) for events PESTICIDES / HERBICIDES (Also disposal of commercial containers) 14,15 PETS ITEMS AND SUPPLIES 15 PHARMACEUTICALS and Over-the-Counter Medicines Disposal 15 PLASTICS RECYCLING – Including plastic shopping bags 15 PRINTER CARTRIDGES 16 PROPANE TANKS 16 RECYCLING CENTERS 16 SHARPS – Needles, injectors, and lancets 17 SHREDDING – Contacting your township for their programs or Recycle Livingston (pg. -

Reuse, Refuse and Recycle Directory Furnished By: Stephanie Blumenthal, Sheffield MA

Reuse, Refuse and Recycle Directory Furnished by: Stephanie Blumenthal, Sheffield MA Items hard to recycle Tires - Mavis charges 2.50 per tire, Seward’s $3.50 per tire, limited as to how many Car parts - George Mielke Used Auto Parts in Sheffield and Drake’s in Lee Sports Equipment - try schools, Scout troops, or the Lion’s Club. Sharing via online groups (e.g. Freecycle.org or a BuyNothingProject Facebook Group CFLs- (compact fluorescent lamp) Home Depot and Lowe’s Stores. Home Depot takes the small ones, not the long ones. Thermostats - free recycling at many plumbing retail stores (search by zip code using “Plumbing Supplies”). For more locations, go to www.thermostat-recycle.org. Smoke & Carbon Monoxide Detectors - see www.curieservices.com Goodwill will not take these Auto waste-antifreeze, used parts Paint, paint thinner Pesticides Mirrors without frames Sleeping bags-homeless shelters and pet shelters Toys-if they have little pieces like Legos All cleaning supplies Skis, ski poles, ski boots-tag sales or Freecycle Exercise equipment- tag sales or Freecycle Recycle Goodwill can take computers, computer monitors, TVs, laptops, e-readers, Portable DVD players and stereos. Bean bag chairs (bean bag filling, expanded polystyrene (EPS) can actually be recycled by separately containing the small beans in a clear plastic bag for your recycling bin). Staples - cell phones, computers, computer monitors, printers, toners, tablets, scanners, and rechargeable batteries, soda stream cylinders, paper shredders Lee Post Office -

SAFETY Xj~R^'J SERIES Respirators and Protective Clothing

This publication is no longer valid Please see http://www-ns.iaea.org/standards/ SAFETY Xj~r^’j SERIES No. 22 Respirators and Protective Clothing INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY VIENNA, 1967 This publication is no longer valid Please see http://www-ns.iaea.org/standards/ This publication is no longer valid Please see http://www-ns.iaea.org/standards/ RESPIRATORS AND PROTECTIVE CLOTHING This publication is no longer valid Please see http://www-ns.iaea.org/standards/ The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN GERMANY, FEDERAL NIGERIA ALBANIA REPUBLIC OF NORWAY ALGERIA GHANA PAKISTAN ARGENTINA GREECE PANAMA AUSTRALIA GUATEMALA PARAGUAY AUSTRIA HAITI PERU BELGIUM HOLY SEE PHILIPPINES BOLIVIA HONDURAS POLAND BRAZIL HUNGARY PORTUGAL BULGARIA ICELAND ROMANIA BURMA INDIA SAUDI ARABIA BYELORUSSIAN SOVIET INDONESIA SENEGAL SOCIALIST REPUBLIC IRAN SIERRA LEONE CAMBODIA IRAQ SINGAPORE CAMEROON ISRAEL SOUTH AFRICA CANADA ITALY SPAIN CEYLON IVORY COAST SUDAN CHILE JAMAICA SWEDEN CHINA JAPAN SWITZERLAND COLOMBIA JORDAN SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC CONGO, DEMOCRATIC KENYA THAILAND REPUBLIC OF KOREA, REPUBLIC OF TUNISIA COSTA RICA KUWAIT TURKEY CUBA LEBANON UKRAINIAN SOVIET SOCIALIST CYPRUS LIBERIA REPUBLIC CZECHOSLOVAK SOCIALIST LIBYA UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLIC LUXEMBOURG REPUBLICS DENMARK MADAGASCAR UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC DOMINICAN REPUBLIC MALI UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT ECUADOR MEXICO BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IREU EL SALVADOR MONACO UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ETHIOPIA MOROCCO URUGUAY FINLAND NETHERLANDS VENEZUELA FRANCE NEW ZEALAND VIET-NAM GABON NICARAGUA YUGOSLAVIA The Agency's Statute was approved on 26 October 1956 by the Conference on the Statute of the IAEA held at United Nations Headquarters, New York; it entered into force on 29 July 1957. -

1 Case 2:18-Cv-04871-GJP Document 11 Filed 04/12/19 Page 1 of 11

Case 2:18-cv-04871-GJP Document 11 Filed 04/12/19 Page 1 of 11 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA MORRIS PARRISH, : Plaintiff, : : v. : CIVIL ACTION NO. 18-CV-4871 : CORRECTIONS EMERGENCY : RESPONSE TEAM (CERT), et al., : Defendants. : MEMORANDUM PAPPERT, J. APRIL 12, 2019 Plaintiff Morris Parrish, a prisoner currently incarcerated at SCI-Phoenix, brings this pro se civil action based on allegations that correctional officers violated his constitutional rights by destroying his property while relocating inmates from the now defunct SCI-Graterford to the newly constructed SCI-Phoenix. The Court screened Parrish’s initial Complaint pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1915A(b) and dismissed it for failure to state a claim, but gave Parrish leave to file an amended complaint. Parrish’s Amended Complaint is currently before the Court. (ECF No. 10.) For the following reasons, the Court will dismiss the Amended Complaint for failure to state a claim pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1915A(b)(1). I The Complaint named as Defendants Secretary John Wetzel, Superintendent Tammy Ferguson, Major Gina Clark, the Corrections Emergency Response Team (CERT)—a group of correctional officers responsible for moving inmate belongings during the transfer between facilities, and various John and Jane Doe Defendants. Parrish alleged that on July 15, 2018, he was “directed to relinquish his personal/legal 1 Case 2:18-cv-04871-GJP Document 11 Filed 04/12/19 Page 2 of 11 property to Doe CERT Member” and that his property was supposed to “join him later after it’s being searched and/or inspected by Doe CERT Member(s).” (Compl. -

Guide to Reuse, Reduce, Recycle and Safe Disposal (Livingston County Does Not Endorse Any Particular Company Or Service.) 2

LIVINGSTON COUNTY GUIDE TO RE-USE RE-DUCE RE-CYCLE & SAFE DISPOSAL This guide was developed to assist residents and businesses of Livingston County dispose of unwanted items in an environmentally friendly manner. This guide is for informational purposes only, and is not an endorsement of the businesses mentioned herein. It is a good practice to always call first to confirm the business or organizations’ services. Livingston County Solid Waste Program 2300 E. Grand River, Suite 105 Howell, MI 48843-7581 Phone: 517-545-9609 www.livgov.com/dpw E-mail: [email protected] This guide is printable on-line. Revised April 29, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Please Note: Livingston County does not endorse any particular company or service. This guide is provided as a service. Information is not guaranteed accurate – please contact the provider. Page Page Ammunition & Explosives 3 Metal (Large Items, Appliances, etc.) 14 Appliances & Large Item Disposal 3 Newspaper / Paper / Shredding 15 Arts & Crafts (including Christmas lights) 4 Office Supplies and Equipment 15 Asbestos 4 Packing or Shipping Materials 15 Audio (See CD’s Page 9) 4 PAINT – Latex & Oil-Based Paints 16 Automobiles (Boats, Trailers, Large Items) 5 Paper Shredding - Check your Township 15 Automotive Fluids 6/7 and/or Recycle Livingston for events Batteries - All types 7 Pesticides / Herbicides 16/17 Battery Drop-off Bucket Locations 8 Pet Items and Supplies 17 Building Materials & Construction Debris 9 Pharmaceuticals (Big Red Barrel Program) 18 CDs –Disks, Video Tapes, DVD, Records 9 Plastic -

Plastic and Human Health: a Micro Issue? ‡ ‡ Stephanie L

Critical Review pubs.acs.org/est Plastic and Human Health: A Micro Issue? ‡ ‡ Stephanie L. Wright*, and Frank J. Kelly MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health, Analytical and Environmental Sciences, King’s College London, London SE1 9NH, United Kingdom *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: Microplastics are a pollutant of environmental concern. Their presence in food destined for human consumption and in air samples has been reported. Thus, microplastic exposure via diet or inhalation could occur, the human health effects of which are unknown. The current review article draws upon cross- disciplinary scientific literature to discuss and evaluate the potential human health impacts of microplastics and outlines urgent areas for future research. Key literature up to September 2016 relating to accumulation, particle toxicity, and chemical and microbial contaminants was critically examined. Although micro- plastics and human health is an emerging field, complementary existing fields indicate potential particle, chemical and microbial hazards. If inhaled or ingested, microplastics may accumulate and exert localized particle toxicity by inducing or enhancing an immune response. Chemical toxicity could occur due to the localized leaching of component monomers, endogenous additives, and adsorbed environmental pollutants. Chronic exposure is anticipated to be of greater concern due to the accumulative effect that could occur. This is expected to be dose-dependent, and a robust evidence-base of exposure levels is currently lacking. Although there is potential for microplastics to impact human health, assessing current exposure levels and burdens is key. This information will guide future research into the potential mechanisms of toxicity and hence therein possible health effects. ■ INTRODUCTION are the most commonly reported form,6 followed by frag- 11 fi ments. -

A Report on Single Use Plastic : 2020

A REPORT BY TOXICS LINK SINGLE USE PLASTIC THE LAST STRAW A watershed moment in the anthropogenic era 2020 About Toxics Link Toxics Link is an Indian environmental research and advocacy organization set up in 1996, engaged in disseminating information to help strengthen the campaign against toxics pollution, provide cleaner alternatives and bring together groups and people affected by this problem. Toxics Link’s Mission Statement - “Working together for environmental justice and freedom from toxics. We have taken upon ourselves to collect and share both information about the sources and the dangers of poisons in our environment and bodies, and information about clean and sustainable alternatives for India and the rest of the world.” Toxics Link has a unique expertise in areas of hazardous, medical and municipal wastes, international waste trade, and the emerging issues of pesticides, Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), hazardous heavy metal contamination etc. from the environment and public health point of view. We have successfully implemented various best practices and have brought in policy changes in the aforementioned areas apart from creating awareness among several stakeholder groups Acknowledgement We would like to thank Mr. Ravi Agarwal, Director, Toxics Link for his continued guidance and encouragement. We would like to thank Mr. Satish Sinha, Associate Director, Toxics Link who guided us through the entire research process and helped us in shaping the study and the report. Our sincere thanks are also due to all team members of Toxics Link for their valuable inputs and suggestions. We would like to give a special thanks to all the respondents in the consumer survey and the informal groups who shared valuable information with us. -

Allowed Items Brochure 5

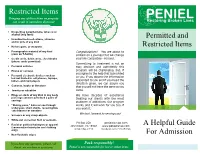

Restricted Items Bringing any of these items on property PENIEL can result in immediate dismissal Restoring Broken Lives ▪ Drugs/drug paraphernalia, tobacco or alcohol (any form) Permitted and ▪ Unauthorized medications, vitamins and/or pills of any kind ▪ Knives guns, or weapons Restricted Items ▪ Pornographic material of any kind (even on T-Shirts) ▪ Credit cards, debit cards, checkbooks (phone cards permitted) ▪ Personal vehicles ▪ House or car keys ▪ Personal electronic devices such as but not limited to cell phones, laptops, tablets and mp3 players ▪ Cameras, books or literature ▪ Jewelry or valuables ▪ Rings or studs of any kind in any body piercings; women permitted 2 pairs of earrings ▪ “Skinny jeans,” bikini or see through underwear, short shorts, revealing/low cuts blouses or sweaters ▪ Scissors or any sharp objects ▪ White-out correction fluid or aerosols PO Box 250 [email protected] ▪ Racial or political hairstyles or apparel A Helpful Guide (conservative hairstyles and clothing Johnstown, PA 15907 www.penielrehab.com only) (814) 536-2111 facebook.com/PenielRehab ▪ Non-flushable wipes For Admission If you have any questions, please call Pack responsibly! ahead, we are here to assist you. Peniel is not responsible for lost or stolen items. Women’s Approved Clothing List Permitted Items Undergarments / Sleepwear * 20 Undergarments For Both Men & Women * 20 undershirts/cami’s/bras Please note: Number of items listed is the limit. Please pack all * 3 slips items in duffel bags and clearly mark each item with your initials. Unlimited -

Personal Protective Equipment Guide

Personal Protective Equipment Guide 1.0 Purpose The purpose of the Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Guide is to provide the campus community with the necessary information to identify work situations that require the use of PPE, determine the proper selection and use of PPE, guidance in the selection of appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), and campus resources for obtaining PPE for employees. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) includes all clothing and work accessories designed to protect employees from workplace hazards. Protective equipment should not replace engineering, administrative, or procedural controls for safety; it should be used in conjunction with these controls. Employees must wear protective equipment as required and when instructed by a supervisor. PPE application should be based on risk assessment, which includes evaluation of the hazard(s) and the procedure used, in consultation with the supervisor or principal investigator (P.I.). 2.0 Responsibilities The following persons / entities have responsibilities as delineated below for implementation of this procedure: 2.1 Risk Management, Office of Environmental Health and Safety It is the responsibility of the Office of Environmental Health and safety to: a) Maintain and update this Procedure as necessary. b) Provide consultation to Deans, Directors, Chairpersons, coordinators, Principal Investigators, managers, and supervisors regarding program compliance. E.H.&S. can provide consultation on such issues as: hazard identification and evaluation; procedures for correcting unsafe conditions; systems for communicating with employees; employee training programs; compliance strategies; and record keeping. 2.2 Deans, Directors, Department Chairs, Department Heads Please see the Cal Poly Injury and Illness Prevention Program, section 7.4 for a detailed description of responsibilities. -

Plastic Transformation Into Jeans

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 10 October 2020 | ISSN: 2320-2882 PLASTIC TRANSFORMATION INTO JEANS Siddharth. Ananthan*1 , Sanjana.Patil 2 , Shraddha.Rahate3, Amit.Sangwan 4, Payal.Dhamale5, Nishchita.Venkatesh6 Amity School Of Applied Science(ASAS), MSc. Chemistry, Amity University, Bhatan Road, Panvel Abstract: Plastic consumption by humans have been increasing year by year and piling up a lot of plastic waste. Around 20 million tonnes of plastic is still being used currently. An average Indian uses 11kg of plastic per year and an American uses 109kg of plastic per year. In this current horrifying situation, clothing world has taken a surprise turn by transforming plastic into clothing apparels such as jeans, shoes, shirts, t-shirts, etc. This additive property of plastic is very advantageous in clothing industry such as increasing of water resistivity , removal of staining problem, increasing the wear and tear of the clothing material, durability of clothes. In this article we'll focus mainly on the plastic to clothing transformation, types of machineries being used for this production, how are the clothes being prepared, which all brands are using these ideas to reduce the wastage of plastic will all be summed up in this article. Keywords: water resistivity, clothing transformations, staining problem, reduction of plastic waste. Introduction: Plastic Pollution has become the biggest major issue in today’s generation1. Growth of usage of plastic has been increasing rapidly by human beings due to which it is affecting our environment2-3. Plastic usually consists out of synthetic, semi-synthetic and organic polymers of higher molecular weight and complex structures present due to which it is non-biodegradable and non-soluble in solvents4-5. -

Erin A. Geagon MFA Thesis

ACCESS DENIED The use of commodities as medium to drive narrative in art Erin A. Geagon MFA Thesis Exhibition University of Georgia Lamar Dodd School of Art April 7 - March 20, 2018 Statement and Objective The foundation of my current art practice is rooted in a deep desire to utilize fabric waste in the creation of functional, utilitarian objects – commodities – in order to extend the life of mass produced textiles and prevent unnecessary and premature disposal of useable fabric into landfill. Once created, I propose that these utilitarian objects, functionally unaltered, can be used as media in the creation of art forms that convey complex narrative information while adhering to formal aesthetic requirements. Drawing on my personal history, my thesis exhibition uses objects commonly found in a domestic environment to address the relationships between family members, particularly parent and child, in a dysfunctional, traditionally patriarchal family structure, where access to inflowing commodities was strictly regulated by the adults and meted out on the basis of deservedness; deservedness being calculated on material contribution to familial wealth. While this story is pointedly focused, containing narrative and referents that cannot be widely known or understood by the average viewer, I believe that the forms lend themselves to a variety of interpretations. Each viewer, utilizing their own experience with commodities, such as blankets and chairs, along with their experience of concepts such as “home” and “family”, may analyze and understand the installation, and each separate artwork within the installation, on their own level even without prior knowledge of the artist’s specific intentions. Introduction When I began my graduate studies at the University of Georgia in the fall of 2015 I had grandiose ideas about utilizing waste and alternative materials in the design and manufacture of fabrics for home furnishing applications. -

Halloween Clothing & Costumes Survey 2019

Halloween Clothing & Costumes Survey 2019 Fairyland Trust/ Hubbub October 2019 Author: Chris Rose [email protected] for www.fairylandtrust.org @campaignstrat @fairylandtrust Contact: 07881 824752 01328 711526 Researcher: Amazon Rose This survey was part-funded by Hubbub working in partnership with the Fairyland Trust Hubbub https://www.hubbub.org.uk/ @hubbubUK Contact: Trewin Restorick [email protected] 1 CONTENTS Section Page Summary 2 Introduction 4 What Can Be Done ? 5 The Survey 7 Results 8 Individual Retailer Results 12 Weights 23 Waste Generated 23 The Popularity of Halloween 24 Conclusions 25 2 SUMMARY An October 2019 survey of 19 retailers by the family nature charity Fairyland Trust supported by Hubbub, estimates that UK Halloween celebrations generate over two thousand tonnes of plastic waste from clothing and costumes alone. The investigation found that 83% of the material in 324 clothing items promoted through online platforms of retailers was oil-based plastic. The study estimates that this is equivalent by weight of waste plastic to 83 million Coca Cola bottles, over one per person in the UK. The retailers surveyed were Aldi, Argos, ASOS, Amazon, Boden, Boohoo, Ebay, H & M, John Lewis, Marks and Spencer, Matalan, Next, PrettyLittleThing, Sainsburys, Tesco, TK MAXX, Topshop, Wilko, Zara. Fairyland Trust says ‘the scariest thing about Halloween is now plastic’. Other research has shown that more than 30m people dress up for Halloween, over 90% of families consider buying costumes, some 7m Halloween costumes are thrown away in the UK each year, and globally less than 13% of material inputs to clothing manufacture are recycled and only 1% of clothing textiles are recycled into new clothes.