Fibershed Clothing Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout

English by Alain Stout For the Textile Industry Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Compiled and created by: Alain Stout in 2015 Official E-Book: 10-3-3016 Website: www.TakodaBrand.com Social Media: @TakodaBrand Location: Rotterdam, Holland Sources: www.wikipedia.com www.sensiseeds.nl Translated by: Microsoft Translator via http://www.bing.com/translator Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Table of Contents For Word .............................................................................................................................. 5 Textile in General ................................................................................................................. 7 Manufacture ....................................................................................................................... 8 History ................................................................................................................................ 9 Raw materials .................................................................................................................... 9 Techniques ......................................................................................................................... 9 Applications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Textile trade in Netherlands and Belgium .................................................................... 11 Textile industry ................................................................................................................... -

Spinning Alpaca: Fiber from Huacaya Alpaca to Suri Alpaca (And Beyond)

presents A Guide to Spinning Alpaca: Fiber from Huacaya Alpaca to Suri Alpaca (and beyond) ©F+W Media, Inc. ■ All rights reserved ■ F+W Media grants permission for any or all pages in this issue to be copied for personal use Spin.Off ■ spinningdaily.com ■ 1 oft, long, and available in a range of beautiful natural colors, alpaca can be a joy to spin. That is, if you know what makes it different from the sheep’s wool most spinners start with. It is Sa long fiber with no crimp, so it doesn’t stretch and bounce the way wool does. Sheep’s wool also contains a lot of lanolin (grease) and most spinners like to scour the wool to remove excess lanolin before they spin it. Alpaca doesn’t have the same grease content, so it can be spun raw (or unwashed) pretty easily, though it may contain a lot of dust or vegetable matter. Alpaca fiber also takes dye beautifully—you’ll find that the colors will be a little more muted than they would be on most sheep’s wool because the fiber is not lustrous. Because alpaca fiber doesn’t have crimp of wool, the yarn requires more twist to stay together as well as hold its shape over time. If you spin a softly spun, thick yarn, and then knit a heavy sweater, the garment is likely to grow over time as the fiber stretches. I hadn’t much experience spinning alpaca until I started volunteering at a school with a spinning program and two alpacas on the working farm that is part of the campus. -

Pre-Departure Information

Pre-Departure Information FROM FRANCE TO SPAIN: HIKING IN THE BASQUE COUNTRY Table of Contents TRAVEL INFORMATION Passport Visas Money Tipping Special Diets Communications Electricity MEDICAL INFORMATION Inoculations Staying Healthy HELPFUL INFORMATION Photography Being a Considerate Traveler Words and Phrases PACKING LIST The Essentials WT Gear Store Luggage Notes on Clothing Clothing Equipment Personal First Aid Supplies Optional Items Reminders Before You Go WELCOME! We’re delighted to welcome you on this adventure! This booklet is designed to guide you in the practical details for preparing for your trip. As you read, if any questions come to mind, feel free to give us a call or send us an email—we’re here to help. PLEASE SEND US Trip Application: Complete, sign, and return your Trip Application form as soon as possible if you have not already done so. Medical Form: Complete, sign, and return your Medical Form as soon as possible if you have not already done so. Air Schedule: Please forward a copy of your email confirmation, which shows your exact flight arrival and departure times. Refer to the Arrival & Departure section of the Detailed Itinerary for instructions. Please feel free to review your proposed schedule with Wilderness Travel before purchasing your tickets if you have any questions about the timing of your arrival and departure flights or would like to confirm we have the required minimum number of participants to operate the trip. Vaccination Card: Please send us a photo or scanned copy of your completed Covid-19 Vaccination Card if you have not already done so. -

Livingston County Guide To

LIVINGSTON COUNTY GUIDE TO RE-USE RE-DUCE RE-CYCLE & SAFE DISPOSAL This guide was developed to assist residents and businesses of Livingston County dispose of unwanted items in an environmentally friendly manner. This guide was designed for informational purposes only. This guide is not an endorsement of the businesses mentioned herein. It is a good practice to always call first to confirm the business or organizations’ services. Livingston County Solid Waste Program 2300 E. Grand River, Suite 105 Howell, MI 48843-7581 Phone: 517-545-9609 www.livgov.com/dpw E-mail: [email protected] Revised 2-2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page/s AMMUNITION & EXPLOSIVES 3 APPLIANCES & LARGE ITEM DISPOSAL 3 ARTS & CRAFTS SUPPLIES (including recycling Christmas lights) 4 ASBESTOS 4 AUDIO – See: CDs, Disks, Video Tapes, Albums, Records 4 AUTOMOBILES 5 AUTOMOTIVE FLUIDS 6 BATTERIES – All types (and locations of the drop-off buckets) 7, 8 BUILDING MATERIALS & CONSTRUCTION DEBRIS 7 CDs – Disks, Tapes, Video Tapes, Albums, Records & DVDs 9 CELLULAR PHONES 9 CLOTHING & SHOES 9 COMPUTERS & ELECTRONICS 10 DUMPS (See Landfills) 10 EYEGLASSES & HEARING AIDS 10 FIRE EXTINGUISHERS 10 FLUORESCENT BULBS AND TUBES 10 FOOD ITEMS 11 FURNITURE AND LARGE ITEMS – Donation or Disposal 11 HOUSEHOLD HAZARDOUS WASTE 11 LANDFILLS, DUMPS AND TRANSFER STATIONS 12 LAWN & GARDEN EQUIPMENT 12 MERCURY – Thermometers, Thermostats 12,18 METAL 13 NEWSPAPER 13 OFFICE SUPPLIES AND EQUIPMENT 13 PACKAGING or SHIPPING MATERIALS 14 PAINT – Latex & Oil-Based Paints 14 PAPER SHREDDING-Check with your Townships and/or Recycle Livingston (pg. 16) for events PESTICIDES / HERBICIDES (Also disposal of commercial containers) 14,15 PETS ITEMS AND SUPPLIES 15 PHARMACEUTICALS and Over-the-Counter Medicines Disposal 15 PLASTICS RECYCLING – Including plastic shopping bags 15 PRINTER CARTRIDGES 16 PROPANE TANKS 16 RECYCLING CENTERS 16 SHARPS – Needles, injectors, and lancets 17 SHREDDING – Contacting your township for their programs or Recycle Livingston (pg. -

Cuticle and Cortical Cell Morphology of Alpaca and Other Rare Animal Fibres

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Institucional Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Chota The Journal of The Textile Institute ISSN: 0040-5000 (Print) 1754-2340 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tjti20 Cuticle and cortical cell morphology of alpaca and other rare animal fibres B. A. McGregor & E. C. Quispe Peña To cite this article: B. A. McGregor & E. C. Quispe Peña (2017): Cuticle and cortical cell morphology of alpaca and other rare animal fibres, The Journal of The Textile Institute, DOI: 10.1080/00405000.2017.1368112 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00405000.2017.1368112 Published online: 18 Sep 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 7 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tjti20 Download by: [181.64.24.124] Date: 25 September 2017, At: 13:39 THE JOURNAL OF THE TEXTILE INSTITUTE, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/00405000.2017.1368112 Cuticle and cortical cell morphology of alpaca and other rare animal fibres B. A. McGregora and E. C. Quispe Peñab aInstitute for Frontier Materials, Deakin University, Geelong, Australia; bNational University Autonoma de Chota, Chota, Peru ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The null hypothesis of the experiments reported is that the cuticle and cortical morphology of rare Received 6 March 2017 animal fibres are similar. The investigation also examined if the productivity and age of alpacas were Accepted 11 August 2017 associated with cuticle morphology and if seasonal nutritional conditions were related to cuticle scale KEYWORDS frequency. -

Connecting Alaska's Fiber Community

T HE A L A SK A N at UR A L F IBER B USI N ESS A SSOCI at IO N : Connecting Alaska’s Fiber Community Jan Rowell and Lee Coray-Ludden one-and-a-half day workshop in the fall of 2012 rekindled a passion for community AFES Miscellaneous Publication MP 2014-14 among Alaska’s fiber producers and artists. “Fiber Production in Alaska: From UAF School of Natural Resources & Extension Agriculture to Art” provided a rare venue for fiber producers and consumers A Agricultural & Forestry Experiment Station to get together and share a strong common interest in fiber production in Alaska. The workshop was sponsored by the Alaska State Division of Agriculture and organized by Lee Coray-Ludden, owner of Shepherd’s Moon Keep and a cashmere producer. There is nothing new about fiber production in Alaska. The early Russians capitalized on agricultural opportunities wherever they could and domestic sheep and goats were a mainstay in these early farming efforts. But even before the Russians, fiber was historically used for warmth by Alaska’s indigenous people. They gathered their fiber from wild sources, and some tribes handspun it and wove it into clothing, Angora rabbits produce a soft and silky creating beautiful works of art. fiber finer than cashmere. Pictured below is Some of the finest natural fibers in the world come from animals that evolved in Michael, a German angora, shortly before cold, dry climates, and many of these animals are grazers capable of thriving on Alaska’s shearing. Angora rabbits may be sheared, natural vegetation. -

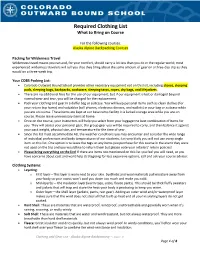

Required Clothing List What to Bring on Course

Required Clothing List What to Bring on Course For the following courses: Alaska Alpine Backpacking Courses Packing for Wilderness Travel Wilderness travel means you can and, for your comfort, should carry a lot less than you do in the regular world; most experienced wilderness travelers will tell you that they bring about the same amount of gear on a three-day trip as they would on a three-week trip. Your COBS Packing List: • Colorado Outward Bound School provides other necessary equipment not on this list, including stoves, sleeping pads, sleeping bags, backpacks, cookware, sleeping tarps, ropes, dry bags, and lifejackets. • There are no additional fees for the use of our equipment, but if our equipment is lost or damaged beyond normal wear and tear, you will be charged for the replacement. • Pack your clothing and gear in a duffel bag or suitcase. You will keep personal items such as clean clothes (for your return trip home) and valuables (cell phones, electronic devices, and wallets) in your bag or suitcase while you are on course. These items are kept at our base camp facility in a locked storage area while you are on course. Please leave unnecessary items at home. • Once on the course, your instructors will help you select from your luggage the best combination of items for you. They will assess your personal gear, the group gear you will be required to carry, and then balance it against your pack weight, physical size, and temperature for the time of year. • Since this list must accommodate ALL the weather conditions you may encounter and consider the wide range of individual preferences and body temperatures of our students, it is very likely you will not use every single item on this list. -

Carbonx Ultimate Baselayer Solutions Include: Long-Sleeve Tops And

“MY HUSBAND WAS AT WORK IN A STEEL THE CARBONX ULTIMATE BASELAYER—THE ONLY MILL, ON A BOBCAT PUSHING HOT SLAG. CHOICE WHEN SAFETY MATTERS MOST HOT MET COLD AND MOLTEN SLAG Flame-resistant (FR) undergarments play an EXPLODED ALL OVER HIS BODY. THE essential role in protecting wearers against STEEL MELTED THE SAFETY BELT ON THE serious burn injuries and more common BOBCAT SO HE COULDN’T FREE HIMSELF. nuisance burns. In dangerous situations, HE WAS WEARING THE NORMAL STEEL having this base layer of defense close to the skin may buy the wearer critical time to MILL GREENS, BUT HE HAD ALSO WORN escape without severe or life-threatening HIS CARBONX UNDERWEAR THAT NIGHT injuries. DUE TO THE COLD EVENING. THE GREENS HE WAS WEARING BURNT OFF OF HIM The CarbonX® UltimateTM Baselayer ALMOST COPLETELY. THE CARBONX HOOD provides the highest level of protection for professionals working in extreme AND UNDERWEAR HE HAD ON SAVED HIS conditions where safety matters most. It is LIFE.” also an ideal choice for cooler climates and winter conditions. The Ultimate Baselayer —WIFE OF A STEEL MILL ACCIDENT VICTIM is made from our DJ-77 black fabric, an 8 oz/yd2 double jersey interlock knit comprised of a propriety blend of high- performance fibers. Constructed to be truly non-flammable, our Ultimate Baselayer delivers: Unmatched Protection: It will not burn, melt, or ignite, and significantly outperforms competing FR products when subjected to direct flame, extreme heat, molten metal, flammable liquids, certain chemicals, and arc flash. Even after intense exposure, our Ultimate Baselayer maintains its strength and integrity and continues ULTIMATE BASELAYER ULTIMATE THAT SOLUTIONS TOE HEAD TO COVER to protect. -

Reuse, Refuse and Recycle Directory Furnished By: Stephanie Blumenthal, Sheffield MA

Reuse, Refuse and Recycle Directory Furnished by: Stephanie Blumenthal, Sheffield MA Items hard to recycle Tires - Mavis charges 2.50 per tire, Seward’s $3.50 per tire, limited as to how many Car parts - George Mielke Used Auto Parts in Sheffield and Drake’s in Lee Sports Equipment - try schools, Scout troops, or the Lion’s Club. Sharing via online groups (e.g. Freecycle.org or a BuyNothingProject Facebook Group CFLs- (compact fluorescent lamp) Home Depot and Lowe’s Stores. Home Depot takes the small ones, not the long ones. Thermostats - free recycling at many plumbing retail stores (search by zip code using “Plumbing Supplies”). For more locations, go to www.thermostat-recycle.org. Smoke & Carbon Monoxide Detectors - see www.curieservices.com Goodwill will not take these Auto waste-antifreeze, used parts Paint, paint thinner Pesticides Mirrors without frames Sleeping bags-homeless shelters and pet shelters Toys-if they have little pieces like Legos All cleaning supplies Skis, ski poles, ski boots-tag sales or Freecycle Exercise equipment- tag sales or Freecycle Recycle Goodwill can take computers, computer monitors, TVs, laptops, e-readers, Portable DVD players and stereos. Bean bag chairs (bean bag filling, expanded polystyrene (EPS) can actually be recycled by separately containing the small beans in a clear plastic bag for your recycling bin). Staples - cell phones, computers, computer monitors, printers, toners, tablets, scanners, and rechargeable batteries, soda stream cylinders, paper shredders Lee Post Office -

SAFETY Xj~R^'J SERIES Respirators and Protective Clothing

This publication is no longer valid Please see http://www-ns.iaea.org/standards/ SAFETY Xj~r^’j SERIES No. 22 Respirators and Protective Clothing INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY VIENNA, 1967 This publication is no longer valid Please see http://www-ns.iaea.org/standards/ This publication is no longer valid Please see http://www-ns.iaea.org/standards/ RESPIRATORS AND PROTECTIVE CLOTHING This publication is no longer valid Please see http://www-ns.iaea.org/standards/ The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN GERMANY, FEDERAL NIGERIA ALBANIA REPUBLIC OF NORWAY ALGERIA GHANA PAKISTAN ARGENTINA GREECE PANAMA AUSTRALIA GUATEMALA PARAGUAY AUSTRIA HAITI PERU BELGIUM HOLY SEE PHILIPPINES BOLIVIA HONDURAS POLAND BRAZIL HUNGARY PORTUGAL BULGARIA ICELAND ROMANIA BURMA INDIA SAUDI ARABIA BYELORUSSIAN SOVIET INDONESIA SENEGAL SOCIALIST REPUBLIC IRAN SIERRA LEONE CAMBODIA IRAQ SINGAPORE CAMEROON ISRAEL SOUTH AFRICA CANADA ITALY SPAIN CEYLON IVORY COAST SUDAN CHILE JAMAICA SWEDEN CHINA JAPAN SWITZERLAND COLOMBIA JORDAN SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC CONGO, DEMOCRATIC KENYA THAILAND REPUBLIC OF KOREA, REPUBLIC OF TUNISIA COSTA RICA KUWAIT TURKEY CUBA LEBANON UKRAINIAN SOVIET SOCIALIST CYPRUS LIBERIA REPUBLIC CZECHOSLOVAK SOCIALIST LIBYA UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLIC LUXEMBOURG REPUBLICS DENMARK MADAGASCAR UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC DOMINICAN REPUBLIC MALI UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT ECUADOR MEXICO BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IREU EL SALVADOR MONACO UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ETHIOPIA MOROCCO URUGUAY FINLAND NETHERLANDS VENEZUELA FRANCE NEW ZEALAND VIET-NAM GABON NICARAGUA YUGOSLAVIA The Agency's Statute was approved on 26 October 1956 by the Conference on the Statute of the IAEA held at United Nations Headquarters, New York; it entered into force on 29 July 1957. -

Winter Hut Trip Packing List

Red Rock Recovery Center Experiential Program Packing List Winter Winter Boots Insulated, waterproof, and above the ankle. Available at Wal-Mart: Men’s Ozark Trail winter boots- $29.84 Men’s winter boots (grey moon boots)- $19.68 Women’s Ozark Trail winter boots- $46.86 Available at REI: Women’s and men’s Sorel Caribou boots- $150 Men’s Kamik William snow boot- $149.95 Men’s North Face Chilkat- $150 Available at Sportsman’s Warehouse: Women’s Northside Kathmandu boots- $74.99 Women’s Northside Bishop Boots- $54.99 Women’s Kamik Momentum- $84.99 Men’s Kamik Nation Plus boots- $79.99 Socks 2 heavy weight wool. No cotton. Available at Wal-Mart: Men’s Kodiak wool socks (2 pack)- $9.48 Men’s Dickies crew work socks- $8.77 Available at REI: REI Coolmax midweight hiking crew socks- $13.95 Fox River Adventure cross terrain 2 pack- $19.95 Available at Sportsman’s Warehouse: Fox River boot and field thermal socks $7.99 Fox River work thermal 2 pack- $15.99 Available at Army/Navy Surplus: Fox River hike, trek, and trail- $8.99 Available at Army/Navy Surplus Outlet: Fox River work steel toe crew 6 pack- $20 Long Underwear 1 set, top & bottom. Midweight, heavyweight, or "expedition weight”. Base layers should be synthetic, silk, or wool. Look for new anti-microbial fabrics that don't get stinky. No cotton. Available at Wal-Mart: Women’s Climate Right by CuddlDuds long sleeve crew and leggings- $9.96 each Men’s Russel base layers top and bottom- $12.72 each Available at Sportsman’s Warehouse: Coldpruf enthusiast base layer top and bottom- $17.99 each Sweater Heavy fleece, synthetic, thin puffy, or wool. -

Nomex® Undergarments Hearing Protection

Prices shown are current as of January 16, 2019. Nomex® Undergarments OMP Nomex® Undergarments, FIA and SFI Approved OMP Sport Nomex® Undergarments, FIA and SFI Approved SAFETY OMP Undergarment Measurements Top Bottom Order Chest Waist Size Size Size S 34 - 36" 29 - 32" M 37 - 39" 33 - 34" L 40 - 42" 35 - 37" OMP Sport Undergarment XL 43 - 46" 38 - 40" Measurements Top Bottom XXL 47 - 50" 41 - 46" Order Chest Waist Inseam are constructed of a very smooth, soft knit fabric. OMP Nomex® Undergarments Size Size Size This is not the typical "waffle weave" long underwear! External seams further enhance comfort and reduce pressure points. The Top features long sleeves and a short mock S 36 - 39" 29 - 32" 28 - 31" turtleneck. The Bottoms have full-length legs, a narrow elastic waist for comfort, and no fly to compromise safety. The two-layer Balaclava features a single large eye opening M 39 - 42" 33 - 34" 30 - 32" and a sculpted neck to prevent bunching above the shoulders. All are FIA 8856-2000 and L 42 - 45" 35 - 37" 32 - 34" SFI 3.3 approved. Natural off-white color only. OMP Nomex® Underwear Top, FIA & SFI ....... Part No. 2153-005-Size .......... $109.00 XL 45 - 48" 38 - 40" 33 - 35" OMP Nomex® Underwear Bottom, FIA & SFI ... Part No. 2153-006-Size ........... $89.00 XXL 48 - 51" 41 - 46" 34 - 36" OMP Nomex® 2-Layer Balaclava, FIA & SFI..... Part No. 2153-001 ................ $49.00 OMP Nomex® Socks, FIA & SFI, pair ............ Part No. 2153-002-Size ........... $29.00 1 are designed and manufactured with the Socks are available in Small (shoe sizes 5 ⁄2 - 8), Medium (8 - 10), and Large (10 - 13).