Territorial Autonomy in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom in the Americas Today

www.freedomhouse.org Freedom in the Americas Today This series of charts and graphs tracks freedoms trajectory in the Americas over the past thirty years. The source for the material in subsequent pages is two global surveys published annually by Freedom House: Freedom in the World and Freedom of the Press. Freedom in the World has assessed the condition of world freedom since 1972, providing separate numerical scores for each countrys degree of political rights and civil liberties as well as designating countries as free, partly free, and not free. Freedom of the Press assesses the level of media freedom in each country in the world and designates countries as free, partly free, and not free. The graphs and charts in this package tell a story that is both encouraging and a source of concern. When Freedom House launched its global index of political rights and civil liberties, freedom was on the defensive throughout much of the Americas. Juntas, military councils, and strongmen held the reins of power throughout much of south and Central America. At various times dictatorships prevailed in such key countries as Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Chile, as well as in every country of Central America except Costa Rica. Latin America was not alone in the grim picture it presented as democracy was by and large restricted to the countries of Western Europe and North America. Conditions in the Americas were strongly influenced by the Cold War. Marxist insurgencies, often employing kidnappings, assassinations, and terrorism, had emerged in a number of countries; military governments responded with extreme brutality, including the use of paramilitary death squads. -

IOM Regional Strategy 2020-2024 South America

SOUTH AMERICA REGIONAL STRATEGY 2020–2024 IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration Av. Santa Fe 1460, 5th floor C1060ABN Buenos Aires Argentina Tel.: +54 11 4813 3330 Email: [email protected] Website: https://robuenosaires.iom.int/ Cover photo: A Syrian family – beneficiaries of the “Syria Programme” – is welcomed by IOM staff at the Ezeiza International Airport in Buenos Aires. © IOM 2018 _____________________________________________ ISBN 978-92-9068-886-0 (PDF) © 2020 International Organization for Migration (IOM) _____________________________________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. PUB2020/054/EL SOUTH AMERICA REGIONAL STRATEGY 2020–2024 FOREWORD In November 2019, the IOM Strategic Vision was presented to Member States. It reflects the Organization’s view of how it will need to develop over a five-year period, in order to effectively address complex challenges and seize the many opportunities migration offers to both migrants and society. It responds to new and emerging responsibilities – including membership in the United Nations and coordination of the United Nations Network on Migration – as we enter the Decade of Action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. -

Federal Systems and Accommodation of Distinct Groups: a Comparative Survey of Institutional Arrangements for Aboriginal Peoples

1 arrangements within other federations will focus FEDERAL SYSTEMS AND on provisions for constitutional recognition of ACCOMMODATION OF DISTINCT Aboriginal Peoples, arrangements for Aboriginal GROUPS: A COMPARATIVE SURVEY self-government (including whether these take OF INSTITUTIONAL the form of a constitutional order of government ARRANGEMENTS FOR ABORIGINAL or embody other institutionalized arrangements), the responsibilities assigned to federal and state PEOPLES1 or provincial governments for Aboriginal peoples, and special arrangements for Ronald L. Watts representation of Aboriginal peoples in federal Institute of Intergovernmental Relations and state or provincial institutions if any. Queen's University Kingston, Ontario The paper is therefore divided into five parts: (1) the introduction setting out the scope of the paper, the value of comparative analysis, and the 1. INTRODUCTION basic concepts that will be used; (2) an examination of the utility of the federal concept (1) Purpose, relevance and scope of this for accommodating distinct groups and hence the study particular interests and concerns of Aboriginal peoples; (3) the range of variations among federal The objective of this study is to survey the systems which may facilitate the accommodation applicability of federal theory and practice for of distinct groups and hence Aboriginal peoples; accommodating the interests and concerns of (4) an overview of the actual arrangements for distinct groups within a political system, and Aboriginal populations existing in federations -

A Look at the Texas Hill Country Following the Path We Are on Today Through 2030

A Look at the Texas Hill Country Following the path we are on today through 2030 This unique and special region will grow, but what will the Hill Country look like in 2030? Growth of the Hill Country The Hill Country Alliance (HCA) is a nonprofit organization whose purpose is to raise public awareness and build community support around the need to preserve the natural resources and heritage of the Central Texas Hill Country. HCA was formed in response to the escalating challenges brought to the Texas Hill Country by rapid development occurring in a sensitive eco-system. Concerned citizens began meeting in September of 2004 to share ideas about strengthening community activism and educating the public about regional planning, conservation development and a more responsible approach growth in the Hill Country. This report was prepared for the Texas Hill Country Alliance by Pegasus Planning 2 Growth of the Hill Country 3 Growth of the Hill Country Table of Contents Executive Summary Introduction The Hill Country Today The Hill Country in 2030 Strategic Considerations Reference Land Development and Provision of Utilities in Texas (a primer) Organizational Resources Materials Reviewed During Project End Notes Methodology The HCA wishes to thank members of its board and review team for assistance with this project, and the authors and contributors to the many documents and studies that were reviewed. September 2008 4 Growth of the Hill Country The Setting The population of the 17-County Hill Country region grew from approximately 800,000 in 1950 (after the last drought on record) to 2.6 million in 2000. -

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: the Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: The Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises A report by the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs and Village Capital With the support of: Ross Baird Lily Bowles Saurabh Lall The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) is a global network of organizations that propel entrepreneurship in emerging markets. ANDE members provide critical financial, educational, and busi- ness support services to small and growing businesses (SGBs) based on the conviction that SGBs will create jobs, stimulate long-term economic growth, and produce environmental and social benefits. Ultimately, we believe that SGBS can help lift countries out of poverty. ANDE is part of the Aspen Institute, an educational and policy studies organization. For more information please visit www.aspeninstitute.org/ande. Village Capital Village Capital sources, trains, and invests in impactful seed-stage enter- prises worldwide. Inspired by the “village bank” model in microfinance, Village Capital programs leverage the power of peer support to provide opportunity to entrepreneurs that change the world. Our investment pro- cess democratizes entrepreneurship by putting funding decisions into the hands of entrepreneurs themselves. Since 2009, Village Capital has served over 300 ventures on five continents building disruptive innovations in agriculture, education, energy, environmental sustainability, financial services, and health. For more information, please visit www.vilcap.com. Report released June 2013 Cover photo by TechnoServe Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Introduction II. Background a. Incubators and Accelerators in Traditional Business Sectors b. Incubators and Accelerators in the Impact Investing Sector III. Data and Methodology IV. -

The Rise of the Territorial State and the Treaty of Westphalia

The Rise of the Territorial State and The Treaty Of Westphalia Dr Daud Hassan* I. INTRODUCTION Territory is one of the most important ingredients of Statehood. It is a tangible attribute of Statehood, defining and declaring the physical area within which a state can enjoy and exercise its sovereignty. I According to Oppenheim: State territory is that defined portion of the surface of the globe which is subject to the sovereignty of the state. A State without a territory is not possible, although the necessary territory may be very smalJ.2 Indispensably States are territorial bodies. In the second Annual message to Congress, December 1. 1862, in defining a Nation, Abraham Lincoln identified the main ingredients of a State: its territory. its people and its law. * Dr Hassan is a lecturer at the Faculty of Law. University of Technology, Sydney. He has special interests in international law. international and comparative environmental law and the law of the sea. The term sovereignty is a complex and poorly defined concept. as it has a long troubled history. and a variety of meanings. See Crawford J, The Creation of States in International Law ( 1979) 26. For example, Hossain identifies three meanings of sovereignty: I. State sovereignty as a distinctive characteristic of states as constituent units of the international legal system: 2. Sovereignty as freedom of action in respect of all matters with regard to which a state is not under any legal obligation: and 3. Sovereignty as the minimum amount of autonomy II hich a state must possess before it can he accorded the status of a sovereign state. -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

Federalism and the Soviet Constitution of 1977: Commonwealth Perspectives

Washington Law Review Volume 55 Number 3 6-1-1980 Federalism and the Soviet Constitution of 1977: Commonwealth Perspectives William C. Hodge Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation William C. Hodge, Federalism and the Soviet Constitution of 1977: Commonwealth Perspectives, 55 Wash. L. Rev. 505 (1980). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol55/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington Law Review by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEDERALISM AND THE SOVIET CONSTITUTION OF 1977: COMMONWEALTH PERSPECTIVES William C. Hodge* INTRODUCTION I. LEGAL NORMS AND ARBITRARY POWER IN THE 1977 CONSTITUTION: AN OVERVIEW OF SOVIET CONSTITUTIONALISM .................... 507 A. Soviet Constitutionalismand the Evolution of Socialist Society ....... 507 B. Rhetoric and Ideology .............................. 512 C. The Role of the Communist Party (CPSU) ............... 513 D. IndividualRights ........ .................... 517 II. FEDERALISM .................................... 519 A. The Characteristicsof Federalism................... 520 B. The Model of Soviet Federalism ................... 523 C. The Validity ofSoviet Federalism...... ................... 527 1. Marxist-Leninist Theory ....... ...................... 527 2. The Vocabulary of Soviet -

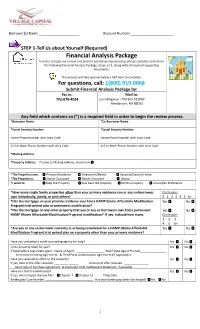

Financial Analysis Package in Order to Begin Our Review and Prevent Any Delays in Processing, Please Complete and Return

Borrower(s) Name Account Number STEP 1-Tell Us about Yourself (Required) Financial Analysis Package In order to begin our review and prevent any delays in processing, please complete and return the following Financial Analysis Package, Steps 1-11, along with all required supporting documents. This process will take approximately a half hour to complete. For questions, call: 1(800) 919-0068 Submit Financial Analysis Package by: Fax to: Mail to: 702-670-4024 Loss Mitigation – PO Box 531667 Henderson, NV 89053 Any field which contains an (*) is a required field in order to begin the review process. *Borrower Name *Co-Borrower Name *Social Security Number *Social Security Number Home Phone Number with Area Code Home Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code *Mailing Address *Property Address If same as Mailing Address, check here *The Property is my: Primary Residence Investment/Rental Seasonal/Second Home *The Property is: Owner Occupied Renter Occupied Vacant *I want to: Keep the Property Give back the property Sell the property Unsure/No Preference *How many single family properties other than your primary residence you or any co-borrowers Circle one: own individually, jointly, or with others? 0 1 2 3 4 5 6+ *Has the mortgage on your primary residence ever had a HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Yes No Program) trial period plan or permanent modification? *Has the mortgage on any other property that you or any co-borrowers own had a permanent Yes No HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Program) modification? If yes, indicate how many. -

Municipal Energy Planning and Energy Efficiency

Municipal Energy Planning and Energy Efficiency Jenny Nilsson, Linköping University Anders Mårtensson, Linköping University ABSTRACT Swedish law requires local authorities to have a municipal energy plan. Each municipal government is required to prepare and maintain a plan for the supply, distribution, and use of energy. Whether the municipal energy plans have contributed to or preferably controlled the development of local energy systems is unclear. In the research project “Strategic Environmental Assessment of Local Energy Systems,” financed by the Swedish National Energy Administration, the municipal energy plan as a tool for controlling energy use and the efficiency of the local energy system is studied. In an introductory study, twelve municipal energy plans for the county of Östergötland in southern Sweden have been analyzed. This paper presents and discusses results and conclusions regarding municipal strategies for energy efficiency based on the introductory study. Introduction Energy Efficiency and Swedish Municipalities Opportunities for improving the efficiency of Swedish energy systems have been emphasized in several reports such as a recent study made for the Swedish government (SOU 2001). Although work for effective energy use has been carried out in Sweden for 30 years, the calculated remaining potential for energy savings is still high. However, there have been changes in the energy system. For example, industry has slightly increased the total energy use, but their use of oil has been reduced by two-thirds since 1970. Meanwhile, the production in the industry has increased by almost 50%. This means that energy efficiency in the industry is much higher today than in the 1970s (Table 1). -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

The Future of the Caucasus After the Second Chechen War

CEPS Working Document No. 148 The Future of the Caucasus after the Second Chechen War Papers from a Brainstorming Conference held at CEPS 27-28 January 2000 Edited by Michael Emerson and Nathalie Tocci July 2000 A Short Introduction to the Chechen Problem Alexandru Liono1 Abstract The problems surrounding the Chechen conflict are indeed many and difficult to tackle. This paper aims at unveiling some of the mysteries covering the issue of so-called “Islamic fundamentalism” in Chechnya. A comparison of the native Sufi branch of Islam and the imported Wahhaby ideology is made, in order to discover the contradictions and the conflicts that the spreading of the latter inflicted in the Chechen society. Furthermore, the paper investigates the main challenges President Aslan Maskhadov was facing at the beginning of his mandate, and the way he managed to cope with them. The paper does not attempt to cover all the aspects of the Chechen problem; nevertheless, a quick enumeration of other factors influencing the developments in Chechnya in the past three years is made. 1 Research assistant Danish Institute of International Affairs (DUPI) 1 1. Introduction To address the issues of stability in North Caucasus in general and in Chechnya in particular is a difficult task. The factors that have contributed to the start of the first and of the second armed conflicts in Chechnya are indeed many. History, politics, economy, traditions, religion, all of them contributed to a certain extent to the launch of what began as an anti-terrorist operation and became a full scale armed conflict. The narrow framework of this presentation does not allow for an exhaustive analysis of the Russian- Chechen relations and of the permanent tensions that existed there during the known history of that part of North Caucasus.