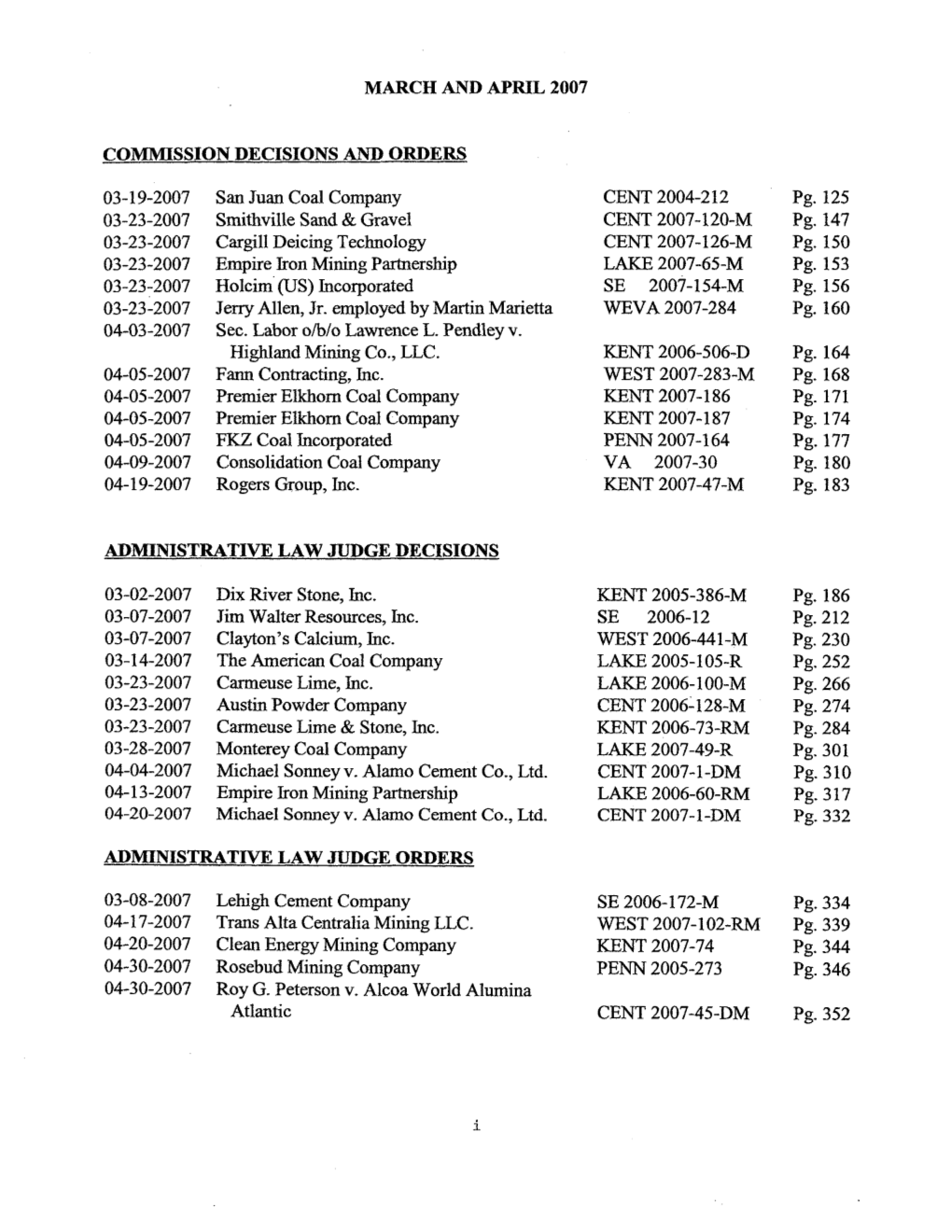

March and April 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kayaking with the Development and Proposed They Participate in the Conservation Foundation Corporate Membership Pro- Gram

•I--'". r: .. *-"•*' •- •- ' .-: ' »<• " -•' ~<r*$ s, -' ' _,' 'ji' '• . " ' i .. * r ' '••• i' *>!.•»*• . •- i ' Shellcrafter Betty Gardner works on shell ornaments at the Sanibel Community House last Monday. Learn more about the Sanibel Shellcrafters — who are busy making goodies for the 70th Annual Sanibel Shell Fair & Show, to be held next March. 2 Q Week of August 11 - August 17, 2006 ISLANDER Water quality snapshots .. Photos by Greg Rawl I provided by PURRE Harbor * P'Ume °r b'°Om Of unknown ori9in in Charlotte Photos from a July 25, 2006 aerial survey of Lee County Blue green algae in the Caloosahatchee downstream of S-79 (Franklin Lock) SigkTseeing-SunseT Cnmses 31 Remal & TOUR Boar TRWS enjoy fnohcking fob/Mm, scewc nanm and SamheVs famous smsers Sanibel Marina SVNCATCHER'S DREAM 631 N ¥ACHKMA\ SAMBE1.IT ? Suncateher's Summer Sale// 2O96 QflF Selected k/ewebyt Lamps, Vases, Ceramics, Emmes (Oft* Bute docteide and enjoy nwuftwaferbg ifcights from the sea It doesn't get any fresher! ocated in the Charming Olde Sanibel Shoppcs 472-8138 LUNCH 1130AM DINNER 5.OOPM TAKE OUT AVAILABLE ext to Amy's O»er Easy Cafe Entertainment nightly in the Piaho Bar & Lounge, Dolce Notte. from around the world while .V m rw. IJLANLV.4 W. • I- •'* AMii.'t 1! - %ii;!ii-| 17, 2006 J 3 Colin Novick from Fairway, Kansas and Alex and Rachel Caffrey from Lee's Summit, Mo. have been shelling "forever," as one of them put It, and on Monday, July 24, just out from Sand Dollar Condominium, they found a cache of cone shells right at the edge of the water. -

Midway FD Is 3Rd Highest Tax Entity

A W A R D ● W I N N I 11BB N G 50¢ YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER August 10, 2006 Midway FD is 3rd in the State! highest tax entity BY BRADLEY “B.J.” DAVIS, JR. County Taxing Authority Gulf Breeze News Gulf Breeze News Florida Press Association C OMPARISON “Best Overall Graphic Design” [email protected] Taxing Authority Taxable value New Construction Taxes According to Santa Rosa Tax Collector Greg Brown, 1. School Board $6,702,089,926 $369,586,023 $50,855,458 Midway Fire District was the Inside in PAGE county’s third highest taxing 2. County $6,575,750,940 $368,825,102 $43,515,031 1B authority for the year, raking in over $1 million more in 3. Midway Fire Dist. $1,507,192,858 $ 59,995,793 $ 2,110,070 property taxes than the City of 4. Gulf Breeze 565,805,304 10,737,829 1,075,030 Gulf Breeze. 2005 taxes for Gulf Breeze were just over 5. Milton 283,648,535 13,101,482 780,033 $1,075,030 whereas 6. NWFWMD 6,702,089,926 369,586,023 335,104 ■ SRIA may extend Midway’s earnings were near- ly double that with $2,110,070 7. Avalon-Mulat 290,974,676 16,602,577 232,779 building timeline generated. ■ Representatives from both 8. Jay 34,305,379 1,291,690 68,610 PBRLA may lose entities were confident that voice at SRIA each was a good steward of Services Paul Stefon/Gulf Breeze News those taxpayer dollars. Gulf C ■ Bubba’s Beach Breeze City Manager Edwin OMPARISON of: She’s a beaut! “Buz” Eddy said the majority GULF BREEZE MIDWAY FIRE Tom Realing of The Northwest Florida Zoological Park and of the taxes collected for the # of Residents 6,000 30,000 (est.) Botanical Gardens wrangles an alligator during a two-day City of Gulf Breeze fund law # of Employees 78 29 project that moved the reptiles to a newly completed exhib- enforcement activities with it. -

Colby Alumnus Vol. 29, No. 8: July 1940

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Colby Alumnus Colby College Archives 1940 Colby Alumnus Vol. 29, No. 8: July 1940 Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Colby College, "Colby Alumnus Vol. 29, No. 8: July 1940" (1940). Colby Alumnus. 243. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus/243 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Alumnus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. �he COLBY IULY,1940 c-A Lu M N us EDUCATED! Where COLBY FOLKS Go Boston New York ,THE NEW YORK HOME Headquarters of the FOR COLBY FOLKS Colby Alumni BOSTON'S FAMOUS Singie 2.50 to $4.00 Dot<ble PARKER $4.00 to $7.00 �pecial Rate<> to HOUSE J4;un1h Grouv.; Write fnr Booklet "C Glenwood J. Sherrard Pre iclent & Managing Director Providence Portland Lewiston Hospitality in PROVIDENCE HOTEL DeWITT 200 Modern Guest Rooms COLUMBIA HOTEL Single $2 to $3.50 Double $3 to $5.00 "The Friendly Hotel" Congres St., at Longfe:Jow Square Princess Restaurant Modern, European, Fireproof Crown Tap Room Good Food and Deep Sea Cocktail Lounge Courteous Service in our Banquet a.nd Convention Facilities Comfortable Rooms Coffee Room Dining Roorr Reasonable Rates Cocktail Lounge Excellent facilities for Popular Priced Restaurant Reunions, Banquets, Dances, Meetings and Conventions Ample Parking Space PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND Garage in Connectior J. Edward Downes, Manager Colby Headquarters in Portland James M. -

Your Best Source for Local Entertainment Information

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, August 8, 2006 Monday Evening August 14, 2006 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Wife Swap Supernanny One Ocean View Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live KBSH/CBS Two Men How I Met Two Men Christine CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Psych Treasure Hunters Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Hell's Kitchen Local Cable Channels A & E Dog Dog Driving Driving Simmons Simmons Flip This House Dog Dog AMC Hustle Hustle The Sting ANIM Gnt Anaconda Caught in the Moment Animal Cops Gnt Anaconda Caught in the Moment CNN Paula Zahn Now Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Norton TV DISC American Hot Rod Biker Build-Off American Chopper American Chopper American Hot Rod DISN Kim Possible: A Sitch in Time Sadie Sadie Dragon The Suite So Raven Phil Kim E! Ryan Seacrest Simple Simple Handler The Soup E! News Daily 10 Saturday Night Live ESPN NFL Football SportsCenter Baseball NFL Live ESPN2 Little League MLB Baseball FAM Kyle XY Falcon Beach Whose? Whose? The 700 Club Kyle XY FX The Rundown '70s Show '70s Show 30 Days Married HGTV Cash in t Cash in t Extreme House House House Design Tech Toys Cash in t Cash in t HIST Stairway B Lost Worlds Dig for Truth UFO Files Stairway B LIFE Killing Mr. Griffin Proof of Lies Will Frasier MTV VMA 06 MTV Cribs MTV Cribs Challenge Challenge MTV Cribs VMA 06 VMA 06 Aguilera Next Listings: NICK SpongeBob Unfab Full Hse. -

1 United States District Court for The

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ________________________________________ ) VIACOM INTERNATIONAL INC., ) COMEDY PARTNERS, ) COUNTRY MUSIC TELEVISION, INC., ) PARAMOUNT PICTURES ) Case No. 1:07-CV-02103-LLS CORPORATION, ) (Related Case No. 1:07-CV-03582-LLS) and BLACK ENTERTAINMENT ) TELEVISION LLC, ) DECLARATION OF WARREN ) SOLOW IN SUPPORT OF Plaintiffs, ) PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR v. ) PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT ) YOUTUBE, INC., YOUTUBE, LLC, and ) GOOGLE INC., ) Defendants. ) ________________________________________ ) I, WARREN SOLOW, declare as follows: 1. I am the Vice President of Information and Knowledge Management at Viacom Inc. I have worked at Viacom Inc. since May 2000, when I was joined the company as Director of Litigation Support. I make this declaration in support of Viacom’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment on Liability and Inapplicability of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act Safe Harbor Defense. I make this declaration on personal knowledge, except where otherwise noted herein. Ownership of Works in Suit 2. The named plaintiffs (“Viacom”) create and acquire exclusive rights in copyrighted audiovisual works, including motion pictures and television programming. 1 3. Viacom distributes programs and motion pictures through various outlets, including cable and satellite services, movie theaters, home entertainment products (such as DVDs and Blu-Ray discs) and digital platforms. 4. Viacom owns many of the world’s best known entertainment brands, including Paramount Pictures, MTV, BET, VH1, CMT, Nickelodeon, Comedy Central, and SpikeTV. 5. Viacom’s thousands of copyrighted works include the following famous movies: Braveheart, Gladiator, The Godfather, Forrest Gump, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Top Gun, Grease, Iron Man, and Star Trek. -

Titulari in Curs De Identificare Trim 3 2015

Difuzari Production Country t Production Year t Title t Grand Total 2003 JUNGLE BEAT 120 2005 MAMA JACK/LEON SCHUSTER'S MAMA JACK 9 2006 7 ANIMALE MAGNIFICE/AFRICA'S SUPER SEVEN 23 24 DIN 7/DISCREET 3 2008 SURORI IN SAFARI/SAFARI SISTERS 46 WILD AFRICA: FISHING & HUNTING 1 2008 Total 50 CAUGHT IN THE ACT 3 2009 IMBLANZIREA LUI TORNADO/RIDING TORNADO 2 SPECIILE SECRETE DIN JAO/THE SECRET CREATURES OF JAO 54 2009 Total 59 CAUGHT IN THE ACT 21 2011 POVESTEA RINOCERULUI PHILA/SAVING RHINO PHILA 8 TIMBAVATI: AN EPIC CAT STORY 18 2011 Total 47 CAUGHT IN THE ACT 35 INGERII-COFETARI AI LUI CHARLY/CHARLY'S BAKERY 26 2012 SPEED KILLS 69 TIMBAVATI: AN EPIC CAT STORY 8 2012 Total 138 AFRICA DE SUD BUCATARIA DE BASM/SARAH GRAHAM COOKS CAPE TOWN 50 CAUGHT IN THE ACT 30 ELEFANTII DIN CASA MEA/ELEPHANTS IN THE ROOM 10 2013 LEOAICA, REGINA ANIMALELOR/THE REAL LION QUEEN 2 POVESTEA MICULUI GHEPARD/CHEETAH RACE TO RULE 13 VIATA DE LEOPARD/LEOPARD FIGHT CLUB 21 2013 Total 126 ANIMALE UCIGASE/GANGLAND KILLERS 191 16 <Prefilter is Empty> 2014 SHARK JUNCTION 16 2014 SPEED KILLS 42 WILD AFRICA: FISHING & HUNTING 2 2014 Total 251 SHARK ALLEY 5 2015 WILD AFRICA: FISHING & HUNTING 3 2015 Total 8 DRAGONS FEAST 7 PRADATORI LA VANATOARE/PREDATORS' PLAYGROUND 23 NECUNOSCUT TOUCHING THE DRAGON 13 WILD AFRICA: FISHING & HUNTING 311 NECUNOSCUT Total 354 AFRICA DE SUD Total 1185 2014 VELE NEGRE (I)/BLACK SAILS (I) 68 AFRICA DE SUD-SUA 2015 VELE NEGRE (II)/BLACK SAILS (II) 48 AFRICA DE SUD-SUA Total 116 ALTELE 2004 ORASELUL LENES/LAZY TOWN 1306 1998-1999 INGER SALBATIC/MUNECA -

Sunflower 05-01-1973 (7.555Mb)

was in honor of the first pres nA 4uii04t la ii lUi^eeJ^^,n(L ident of Fairmouni College, Dr, N.J, Morrison. The columns were formerly located at the front ol lh(! onginal Carnegie Library Colmniis dedicated, lane named There werr* originally eight I olumns, but only ihrer; will ni)w About fifty alumni and guests Spring Reunion last weekend stand on the northeast loiner ol were on hand for the dedication honoring the classes ol '23, ‘28, 1 7 and Fairmount. of the Morrison columns and the '33, '43. '48. '53 and '63. The (olurnns have not yet naming of Isely Lane on campus. The dedication of the relo been erected on thi' site, dur; to The dedications were part of the cation of the Morrison columns bad weather Morrison was instrumental irr securing the $40,n()() Andrew Carnegie conlnbulion to es tahlish thr* library Eleven years in construction, the cornerstone of the new Carnegie I ibrary was laid on March 10, 1908, The library was later renamed Mor rison Library. The 1908 cornerstone was recently opened when construc tion began on the new McKnight Art Building and the old library was torn down. A new cornerstone was laid Saturday where the columns will be located. This is to be opened on the 100th anniversary of Fair mount College in 1995 The street that winds around the back of the CAC, McKinley, and Jardine was named Isely Lane Saturday. The street is named in honor of Dean W.H. Isely, who served with Morrison in the beginning AS they stood originally. -

Episode 5 – Master Adam Grogin | Whistlekickmartialartsradio.Com

Episode 5 – Master Adam Grogin | whistlekickMartialArtsRadio.com Jeremy Lesniak: Hello, welcome to episode 5 of whitslekickMartialArtsRadio, my name is Jeremy Lesniak your host for the show and the president of whistlekick sparring gear and apparel. On today's show, we have Master Adam Grogin, a lifelong Taekwondo student, instructor, promoter and competitor from Northern New York. I met Master Grogin last year when we were introduced by Master Huzon Alexander, you may remember him from episode 1. Master Grogin is a great guy and he's doing more to spread the martial arts than most people I know. You'll see what I mean when we get into the episode. I was really struck by how dedicated he truly is. For some people, the martial arts is a calling and Master Grogin is one of those people. Listen. Master Grogin welcome to whistlekickMartialArtsRadio. Adam Grogin: Hi, how are you today? Jeremy Lesniak: I'm doing great, thanks. I really appreciate you being here. Adam Grogin: Episode 5 – Master Adam Grogin | whistlekickMartialArtsRadio.com Well, I'm really honored to be here so thank you so much for the invitation. I'm really excited about this. Jeremy Lesniak: Oh cool, let's get into it. This should be fun. Why don't you tell us a little bit about your history with the martial arts? Adam Grogin: Let's see so I've been doing martial arts for about 28 years now. My main background is of Korean style Taekwondo, a little bit of all the different types of Taekwondo, ITF, WTF and 01:18 and that. -

Tv Pg 5 7-8.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, July 8, 2008 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle FUN BY THE NUM B ERS will have you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, column and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO FRID A Y ’S TUESDAY EVENING JULY 8, 2008 WEDNESDAY EVENING JULY 9, 2008 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone The First 48 Shooting vic- Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Criss Angel Criss Angel Criss Angel Criss Angel The First 48 Shooting vic- The First 48: Dropped The First 48 (TVPG) (N) CSI: Miami: Shock Spoiled CSI: Miami: Rampage The First 48: Dropped 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E Call; Derailed (R) heiress. (TV14) (TV14) Call; Derailed (R) tims. (TVPG) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) tims. -

Dedicated Hardware for Machine/Deep Learning: Domain Specific Architectures Angel Izael Solis University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2019-01-01 Dedicated Hardware for Machine/Deep Learning: Domain Specific Architectures Angel Izael Solis University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Commons, and the Computer Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Solis, Angel Izael, "Dedicated Hardware for Machine/Deep Learning: Domain Specific Architectures" (2019). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 172. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/172 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEDICATED HARDWARE FOR MACHINE/DEEP LEARNING: DOMAIN SPECIFIC ARCHITECTURES ANGEL IZAEL SOLIS Master’s Program in Computer Engineering APPROVED: Patricia A. Nava, Ph.D. Martine Ceberio, Ph.D. John A. Moya, Ph.D. Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright by Angel Izael Solis 2019 DEDICATION As a child my father was a truck driver and on his long trips on the road, he would play the radio often and listen to reflections. This is the one that has stuck with me my entire life… La vida es en muchas maneras como un tren, Está llena de experiencias y gente, como igual un tren está llena de estaciones, a veces hay cambios de vía y accidentes. Cuando nace unas de las primeras personas que conoce en su tren son sus padres. -

Titulari in Curs De Identificare T2 2015

Difuzari Production Country u Production Year u Title t Grand Total ZIMBABWE 2014 DE LA PUI LA PRADATOR/CUTE TO KILLER 9 UNGARIA-GERMANIA 2008 DELTA/DELTA 1 ADVENTURERS 11 AUTUMN FISHING ADVENTURES WITH KAROLY BOKOR 4 BACK TO SCHOOL 63 BAIATUL DULCE/SWEET BOY 3 BUCATARIA BURLACULUI 7 CARP ZOOM ZONE 38 CATFISH ANGLING WTH KAROLY BOKOR 9 CATFISHING BY NIGHT WITH KAROLY BOKOR 25 CHAMOIS HUNTING IN THE AUSTRIAN ALPS 28 COMPETITION SECRETS 4 FEEDER MANIA 26 FISH FESTIVAL AT LAKE VELENCEI 9 FISHLOVERS KITCHEN 12 HORGASZ SHOW 4 HUNTING FEVER 86 HUNTING FROM SPRING TILL AUTUMN 23 IHR ADVENTURES 274 LARGE DISTANCE CARPFISHING WITH FEEDER 35 LIGHT SPINNING WITH KAROLY BOKOR 4 METODA MODERNA 20 ON BIG CARP'S TRAIL 101 NECUNOSCUT ON THE TRAIL OF SZECHENYI 11 RAPALA SPINNING WITH KAROLY BOKOR 52 RED DEER WEDDING AT FORESTRY SEFAG 21 RESTAURANTUL 'MATYAS PINCE'/A MATYAS PINCE 6 ROE BUCK HUNTING IN BEKES COUNTY 54 17 <Prefilter is Empty> ROE DEER WEDDING IN SUKOSD 17 SBS 104 SEARCHING FOR CARP WITH KAROLY BOKOR 4 SHORT FEEDER ROD FISHING ON SMALL PONDS 12 SPINNING ON DANUBE WITH KAROLY BOKOR 22 STORM ARASHI SPINNING WITH KAROLY BOKOR 28 TARA PESTELUI 30 THE GREAT FLOOD IN GEMENC 21 THE HUNTING MUSEUM KESZTHELY 50 THE SEASON BEGINS IN SEPTEMBER IN JANOSHAZA 3 THE WILD BOAR 38 WILD BOAR DRIVE HUNTING IN NAGYKANIZSA 35 WILD BOAR DRIVE IN ZALA COUNTY 30 WILDWATER ADVENTURES 79 ZANDER SPINNING WITH PLASTIC RULES FROM KAROLY BOKOR 25 ZI DE ZI/NAPROL NAPRA, ZE DNE NA DEN 84 NECUNOSCUT Total 1512 FEEDER MANIA 50 FISHLOVERS KITCHEN 78 HORGASZ SHOW 5 HUNTING FEVER 4 IHR ADVENTURES 135 2015 IN MEMORIAM ZOLTAN PELI 61 INTERNATIONAL BALATON CARP CUP 26 THE HUNTING CAMERAMAN 5 TROUT SPINNING 10 WALTER SOLUTIONS 17 2015 Total 391 7TH PROFESSIONAL BOILIE EUROPE CUP 21 CARP ZOOM ZONE 76 CATFISH IN THE RAIN 37 20 <Prefilter is Empty> DAMVADASZAT ITT, ES OTT.. -

Kuwait Oks $100M Grant for Iraq, First Since 1990

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, APRIL 26, 2017 RAJAB 29, 1438 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Coptic Pope Ivanka forced Thai man Warriors come says Church to defend Trump broadcasts out swinging, bombings aim at Germany daughter’s murder complete sweep at Egypt5 unity women’s7 summit live12 on Facebook of20 Trail Blazers Kuwait OKs $100m grant Min 23º Max 32º for Iraq, first since 1990 High Tide 11:38 Low Tide Kuwait earmarks $100m for Yemen, $1.1bn pledged 05:48 & 18:16 40 PAGES NO: 17210 150 FILS KUWAIT/GENEVA: Kuwait has approved a $100 million Conspiracy theories grant for Iraq to support humanitarian and reconstruc- tion projects in areas retaken from Islamic State mili- Grow your own... tants, an Iraqi official said yesterday. The grant is the first Kuwaiti financial assistance to Iraq since Baghdad’s occupation of the state from Aug 1990 to Feb 1991, ordered by then-President Saddam Hussein. Officials from the two countries signed the grant agreement in Kuwait yesterday, a spokeswoman for By Badriya Darwish Iraq’s Reconstruction Fund for Areas Affected by Terrorist Operations said. “The grant agreement signed today is an encouraging start for further future coopera- tion between Iraq and Kuwait,” the reconstruction fund chief, Mustafa Al-Hiti, said in a statement. [email protected] The fund aims to rebuild cities and territories recap- tured from Islamic State, the ultra-hardline group which declared a “caliphate” over parts of Iraq and Syria in 2014. The war with Islamic State escalated as crude ’m fighting with our American editor over social prices tumbled, curtailing the Iraqi government budget media.