Professional Public Relations and Political Power in Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Texas Observer APRIL 17, 1964

The Texas Observer APRIL 17, 1964 A Journal of Free Voices A Window to The South 25c A Photograph Sen. Ralph Yarborough • • •RuBy ss eII lee we can be sure. Let us therefore recall, as we enter this crucial fortnight, what we iciaJ gen. Jhere know about Ralph Yarborough. We know that he is a good man. Get to work for Ralph Yarborough! That is disputed, for some voters will choose to We know that he is courageous. He has is the unmistakable meaning of the front believe the original report. not done everything liberals wanted him to page of the Dallas Morning News last Sun- Furthermore, we know, from listening to as quickly as we'd hoped, but in the terms day. The reactionary power structure is Gordon McLendon, that he is the low- of today's issues and the realities in Texas, out to get Sen. Yarborough, and they will, downest political fighter in Texas politics he has been as courageous a defender of unless the good and honest loyal Demo- since Allan Shivers. Who but an unscrupu- the best American values and the rights of crats of Texas who have known him for lous politician would call such a fine public every person of every color as Sam Hous- the good and honest man he is lo these servant as Yarborough, in a passage bear- ton was; he has earned a secure place in many years get to work now and stay at it ing on the assassination and its aftermath, Texas history alongside Houston, Reagan, until 7 p.m. -

Labor in Politics Mary Goddard Zon*

LABOR IN POLITICS MARY GODDARD ZON* There are now more American trade unionists actively involved in political affairs than ever before in the history of the nation. It is the constant and continuing purpose of the AFL-CIO's Committee on Political Education (COPE) to broaden the base of the electorate. We believe that as each American citizen benefits from assuming an active and responsible role in political decisions, so the nation benefits from a dedicated and informed electorate. This job will never be finished. Each year thousands of youngsters reach voting age. Each year millions of families change residence and face the problem of re- registering under different and sometimes restrictive laws. As technological dis- coveries affect employment opportunities, our members are often forced to move in order to find work. As the nationwide residential pattern shifts from the city to the encircling suburbs, our members move across city, county, and sometimes state lines. The problem of maintaining contact with our mobile membership is growing in complexity. Only a small fraction of the total can be reached at regular union meetings. We are exploring new techniques for communicating with our members and providing them with the tools they seek and the information they demand as the basis for mature political judgment. I LuoR's TRaITONAL POLITICAL ROLE American workers have been in politics since the i73o's when they joined with artisans and shopkeepers to elect Boston town officials. The form of labor organiza- tions and the character and degree of labor's political activity have changed many times in the intervening years. -

American Health Care: Justice, Policy, Reform Carolyn Conti

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 2010 American Health Care: Justice, Policy, Reform Carolyn Conti Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Conti, C. (2010). American Health Care: Justice, Policy, Reform (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/432 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN HEALTH CARE: JUSTICE, POLICY, REFORM A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Carolyn Ann Conti December 2010 Copyright by Carolyn Ann Conti 2010 AMERICAN HEALTH CARE: JUSTICE, POLICY, REFORM By Carolyn Ann Conti Approved October 4, 2010 _________________________________ _________________________________ Aaron L. Mackler, Ph.D. Gerard Magill, Ph.D. Associate Professor Professor Department of Theology Healthcare Ethics Program (Dissertation Director) (Committee Member) _________________________________ Charles J. Dougherty, Ph.D. President Duquesne University (Committee Member) _________________________________ __________________________________ Christopher M. Duncan, Ph.D. Henk Ten Have, M.D., Ph.D Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate Director, Center for Healthcare Ethics School of Liberal Arts Professor, Healthcare Ethics iii ABSTRACT AMERICAN HEALTH CARE: JUSTICE, POLICY, REFORM By Carolyn Ann Conti December 2010 Dissertation supervised by Professor Aaron L. Mackler The American health care system is seriously flawed and in need of reform. American health care is expensive and rationed by the ability to pay. -

PACKAGING POLITICS by Catherine Suzanne Galloway a Dissertation

PACKAGING POLITICS by Catherine Suzanne Galloway A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California at Berkeley Committee in charge Professor Jack Citrin, Chair Professor Eric Schickler Professor Taeku Lee Professor Tom Goldstein Fall 2012 Abstract Packaging Politics by Catherine Suzanne Galloway Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jack Citrin, Chair The United States, with its early consumerist orientation, has a lengthy history of drawing on similar techniques to influence popular opinion about political issues and candidates as are used by businesses to market their wares to consumers. Packaging Politics looks at how the rise of consumer culture over the past 60 years has influenced presidential campaigning and political culture more broadly. Drawing on interviews with political consultants, political reporters, marketing experts and communications scholars, Packaging Politics explores the formal and informal ways that commercial marketing methods – specifically emotional and open source branding and micro and behavioral targeting – have migrated to the political realm, and how they play out in campaigns, specifically in presidential races. Heading into the 2012 elections, how much truth is there to the notion that selling politicians is like “selling soap”? What is the difference today between citizens and consumers? And how is the political process being transformed, for better or for worse, by the use of increasingly sophisticated marketing techniques? 1 Packaging Politics is dedicated to my parents, Russell & Nancy Galloway & to my professor and friend Jack Citrin i CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION Politics, after all, is about marketing – about projecting and selling an image, stoking aspirations, moving people to identify, evangelize, and consume. -

Texas Legislature, Austin, Texas, April 24, 1967

FOR RELEASE: MONDAY PM's APRIL 24, 1967 REMARKS OF VICE PRESIDENT HUBERT H. HUMPHREY TEXAS STATE LEGISLATURE AUSTIN, TEXAS APRIL 24, 1967 This is a very rare experience for me -- to be able to stand here and look out over all these fine Texas faces. Of course, I have had considerable practice looking into Texas faces -- sometimes I get the feeling that whoev·er wrote "The Eyes of Texas rr had me in mind. But what makes this experience so rare is that, this time, I am doing the talking. And I don't mind telling you: You may be in for it. But you don't need to worry. The point has already been made. One of your fellow Texans reminded me this morning that Austin was once the home of William Sidney Porter who wrote the 0. Henry stories -- and he .observed that 0. Henry and I had much in common: 0. Henry stories al'ltfays have surprise endings and in my speeches, the end is always a surprise, too. I am happy to be in Texas once again. As you realize, one of the duties of a Vice President is to visit the capitals of our friendly allies. Believe me; we are very grateful in Washington to have Texas on our side - that is, whenever you are. I am pleased today to bring to the members of the Legislature warm personal greetings from the President of the United States. He is on a sad mission today to pay the last respects of our nation to one of the great statesmen in the postwar world -- a man who visited Austin six years ago this month -- former Chancellor Konrad Adenauer of Germany. -

19-04-HR Haldeman Political File

Richard Nixon Presidential Library Contested Materials Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 19 4 Campaign Other Document From: Harry S. Dent RE: Profiles on each state regarding the primary results for elections. 71 pgs. Monday, March 21, 2011 Page 1 of 1 - Democratic Primary - May 5 111E Y~'ilIIE HUUSE GOP Convention - July 17 Primary Results -- --~ -~ ------- NAME party anncd fiJ cd bi.lc!<ground GOVERNORIS RACE George Wallace D 2/26 x beat inc Albert Brewer in runoff former Gov.; 68 PRES cando A. C. Shelton IND 6/6 former St. Sen. Dr. Peter Ca:;;hin NDPA endorsed by the Negro Democratic party in Aiabama NO SENATE RACE CONGRESSIONAL 1st - Jack Edwards INC R x x B. H. Mathis D x x 2nd - B ill Dickenson INC R x x A Ibert Winfield D x x 3rd -G eorge Andrews INC D x x 4th - Bi11 Nichols INC D x x . G len Andrews R 5th -W alter Flowers INC D x x 6th - John Buchanan INC R x x Jack Schmarkey D x x defeated T ito Howard in primary 7th - To m Bevill INC D x x defeated M rs. Frank Stewart in prim 8th - Bob Jones INC D x x ALASKA Filing Date - June 1 Primary - August 25 Primary Re sults NAME party anned filed bacl,ground GOVERNOR1S RACE Keith Miller INC R 4/22 appt to fill Hickel term William Egan D former . Governor SENATE RACE Theodore Stevens INC R 3/21 appt to fill Bartlett term St. -

Oral History Interview with Clement Sherman Whitaker

California State Archives State Government Oral History Program Oral History Interview with CLEMENT SHERMAN WHITAKER, JR. Political Campaign and Public Relations Specialist, 1944- September 15,27, October 21, November 17, December 7, 1988; January 18,1989 San Francisco, California By Gabrielle Morris Regional Oral History Office University of California, Berkeley RESTRICTIONS ON THIS INTERVIEW None. LITERARY RIGHTS AND QUOTATIONS This manuscript is hereby made available for research purposes only. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the California State Archivist or RegIOnal Oral History Office, University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to: California State Archives 1020 0 Street, Room 130 Sacramento, California 95814 or Regional Oral History Office 486 Library University of California Berkeley, California 94720 The request should include information of the specific passages and identification of the user. It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows: Clement Sherman Whitaker, Jr. Oral History Interview, Conducted 1989 by Gabrielle Morris, Regional Oral History Office, University of California at Berkeley, for the California State Archives State Government Oral History Program. California State Archives Information (916) 445-4293 March Fong Eu Document Restoration (916) 445-4293 10200 Street, Room 130 Secretary of State Exhibit Hall (916) 445-0748 Sacramento, CA 95814 Legislative Bill Service (916) 445-2832 -

Dallas Trip Initiated by Ken

14 CHICAGO DAILY NEWS, Tuesday:2an,1 1967 Dallas Trip Initiated by Ken Democratic National Commit- By Drew Pearson aged to defeat in the final tee. andlack Anderson run-off by only 20,000 voles. During the campaign, Con- AFTER GOV.-elect Con- WASHINGTON—The chief nally had said he was opposed nally's negative response, Pres- reason for Kennedy family bit- to most of Kennedy's program, ident Kennedy checked with terness against L13.1 immedia- while Yarborough supported tely after the assassination was Kennedy. Connally made it Vice President Johnson about the belief that it was the vice clear it would be embarrassing the trip. Mr. Johnson agreed president who had persuaded to have the President come to with Comially and urged delay. John F. Kennedy to go to Texas during the middle of Six months later, in June, Texas. the campaign. 1963, President Kennedy told If it had not been for Mr. After Connally's victory in both Vice President Johnson Johnson's persuasiveness. Ken- November, 1962, McGuire and Gov. Connally that he nedy never would have gone telephoned Connally about the wanted to go to Texas. He to the dangerous anti-Kennedy proposed Kennedy trip and said that McGuire was breath- City of Dallas and would be the fund-raising dinner. Con- ing' down his neck to raise alive today—or so the Ken- nally replied that the time was some Texas money, and that nedy family believes. still not ripe. He wanted to Rep. Thomas was still promis- This has contributed to the pay off his own debt, which ing a big dinner to tap Texas enmity between the two most amounted to nearly $1,500,- millionaires. -

And/Or Attended Local

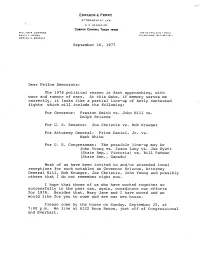

EDWARDS & PERRY ATTORNEYS AT LAW P. O.DRAWER 480 CORPUS CHHMTI, TEXAS 78400 WILLIAM R EDWARDS 935 PETROLEUM TOWER DAVI·) L. PERRY TELEPHONE: (512) 883·0971 MARCEL S. GREENIA September 16, 1977 Dear Fellow Democrats; The 1978 political season is fast approaching, with wars and rumors of wars. At this date, if memory serves me correctly, it looks like a partial line-up of hotly contested fights which will include the following: For Governor: Preston Smith vs. John Hill vs. Dolph Briscoe For U. S. Senator: Joe Christie vs. Bob Krueger For Attorney General: Price Daniel, Jr. vs. Mark White For U. S. Congressman: The possible line-up may be John Young vs. Jason Luby vs. Joe Wyatt (State Rep., Victoria) vs. Bill Patman (State Sen., Ganado) Most of us have been invited to and/or attended local receptions for such notables as Governor Briscoe, Attorney General Hill, Bob Krueger, Joe Christie, John young and possibly others that I do not remember right now. I hope that those of us who have worked together so successfully in the past can, again, coordinate our efforts for 1978. Besides that, Mary Jane and I have moved and we would like for you to come and see our new house. Please come by the house on Sunday, September 25, at 7:00 p.m. We live at 6222 Boca Raton, just off of Congressional and Everhart. This will be an evening to renew friendships, exchange views, find out the extent to which we agree, and, hopefully, limit our disagreements so that they w*r4 not interfer with working together to continue a strong /bem*cr Eicrganiza- tion that can beat John. -

Uncovering Texas Politics in the 21St Century

first edition uncovering texas politics st in the 21 century Eric Lopez Marcus Stadelmann Robert E. Sterken Jr. Uncovering Texas Politics in the 21st Century Uncovering Texas Politics in the 21st Century Eric Lopez Marcus Stadelmann Robert E. Sterken Jr. The University of Texas at Tyler PRESS Tyler, Texas The University of Texas at Tyler Michael Tidwell, President Amir Mirmiran, Provost Neil Gray, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences UT Tyler Press Publisher: Lucas Roebuck, Vice President for Marketing Production Supervisor: Olivia Paek, Agency Director Content Coordination: Colleen Swain, Associate Provost for Undergraduate and Online Education Author Liaison: Ashley Bill, Executive Director of Academic Success Editorial Support: Emily Battle, Senior Editorial Specialist Design: Matt Snyder © 2020 The University of Texas at Tyler. All rights reserved. This book may be reproduced in its PDF electronic form for use in an accredited Texas educational institution with permission from the publisher. For permission, visit www.uttyler.edu/press. Use of chapters, sections or other portions of this book for educational purposes must include this copyright statement. All other reproduction of any part of this book, storage in a retrieval system, or transmission in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except as expressly permitted by applicable copyright statute or in writing by the publisher, is prohibited. Graphics and images appearing in this book are copyrighted by their respective owners as indicated in captions and used with permission, under fair use laws, or under open source license. ISBN-13 978-1-7333299-2-7 1.1 UT Tyler Press 3900 University Blvd. -

Texas Board of Pardons a D Paroles

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. TEXAS BOARD OF PARDONS A D PAROLES THIRTIETH AN VAL ~~TATI§TICAL REPORT September 1, 1976 through August 31, 1977 '~"'~ ..•. -, ......, ... ,:~... ' ... ' .... ,._' . ~"" ' Stephen F 0 Austin Building :t:toom 711 .- Austin, Texas .i NCJf{S MAY 24 '978 '\ J~CQUiSlTlOr'lS ~ THIRTIETH ANr~~'UAL STATISTICAL REPORT Of The BOARD OF PARDONS AND PAROLES George G. Killinger, Ph.D., Chairman September 1, 1976 througb August 31, 1977 Stephen F. Austin Building Room 711- Austin, Texas 78701 , BOARD MEMBERS: ......... GEORGE G. KILLINGER, Ph.D., CHAIRMAN ."t;o(t. 9ifI", PAROLE COMMISSIONERS: SELMA WELLS, VICE·C'·li '".tMAN CL VbE WHITESIDE, MEIVIBi:R NORTHERN UNITS CHARLES G. SHAND ERA CLVPEWHITESIDE, ADMINISTRATOR GILBeRTO DE LEON INTERSTATE PAROLE COMPACT PAUL MANSMANN ~m~-',:' .: ..... DON STILES KEN CASNER ... "' ..:: ..... EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 2Soa LAKE ROAD BOARD OF PARDONS AND PAROLES HUNTSVILLE, TEXAS 77340 PHONE: (713) 291·2161 ROOM 711 STEPHEN F. AUSTIN BUILDING SOUTHERN UNITS AUSTIN, TEXAS HELEN COl'lTKA 78701 EDWARD JOHNSON P. O. BOX 1207 ANGLETON, TEXAS 17515 August 31, 1977 PHONE: (713) 849·3031 Honorable Dolph Briscoe, Governor Honorable Joe R. Greenhill, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Honorable John F. Onion, Jr., Presiding Judge of the Court of Criminal Appeals Members of the Senate and House of Representatives of the State of Texas Gentlemen: In compliance with the provisions of Artiole 42.12, Section 13 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of Texas, we respectfully submit the Annual Report with Statistic 1 and other data relating to the work of the Board 0 ardons and Paroles for the fiscal year ending August 3 977. -

An Analysis and Evaluation of John Connally's May 28, 1971 Speech At

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1973 An Analysis and Evaluation of John Connally's May 28, 1971 Speech at Munich, Germany During the International Monetary Crisis Rita Lynne Colbert Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Speech Communication at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Colbert, Rita Lynne, "An Analysis and Evaluation of John Connally's May 28, 1971 Speech at Munich, Germany During the International Monetary Crisis" (1973). Masters Theses. 3820. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3820 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's