VALUE ASSESSMENT of HISTORIC FORT PRECINCTS of MUMBAI a User-Centric Approach to Analyzing Significance of Forts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

The Victorian and Art Deco Ensemble of Mumbai (India) No 1480

Consultations ICOMOS consulted its International Scientific Committees The Victorian and Art Deco Ensemble on Shared Built Heritage, on 20th Century Heritage, on of Mumbai Historic Towns and Villages, and several independent experts. (India) No 1480 Technical Evaluation Mission A technical evaluation mission from ICOMOS visited the nominated property from 6 to 11 September 2017. Additional information received by ICOMOS Official name as proposed by the State Party A letter was sent from ICOMOS to the State Party on The Victorian and Art Deco Ensemble of Mumbai 1 August 2017 requesting updated information on the nomination dossier, particularly on issues of protection Location management and conservation. Also, additional Mumbai, Maharashtra State information was requested regarding the boundaries of India the property and the buffer zone, justification for inscription, the resolution of the submitted maps, and Brief description questions about management and protection. A The demolition of the fortifications of Bombay in the 1860s response with additional information was received by marked the transformation of the city from a fortified ICOMOS from the State Party on 5 September 2017. outpost into a world class commercial centre and made available land for development. A group of public An Interim Report was sent to the State Party on buildings was built in the Victorian Gothic style and the 22 December 2017 and the State Party provided open green space of the Oval Maidan was created. The ICOMOS with additional information on 13 February th Backbay Reclamation Scheme in the early 20 century 2018. The information submitted has been incorporated offered a new opportunity for Bombay to expand to the in the relevant sections of this report. -

CRAMPED for ROOM Mumbai’S Land Woes

CRAMPED FOR ROOM Mumbai’s land woes A PICTURE OF CONGESTION I n T h i s I s s u e The Brabourne Stadium, and in the background the Ambassador About a City Hotel, seen from atop the Hilton 2 Towers at Nariman Point. The story of Mumbai, its journey from seven sparsely inhabited islands to a thriving urban metropolis home to 14 million people, traced over a thousand years. Land Reclamation – Modes & Methods 12 A description of the various reclamation techniques COVER PAGE currently in use. Land Mafia In the absence of open maidans 16 in which to play, gully cricket Why land in Mumbai is more expensive than anywhere SUMAN SAURABH seems to have become Mumbai’s in the world. favourite sport. The Way Out 20 Where Mumbai is headed, a pointer to the future. PHOTOGRAPHS BY ARTICLES AND DESIGN BY AKSHAY VIJ THE GATEWAY OF INDIA, AND IN THE BACKGROUND BOMBAY PORT. About a City THE STORY OF MUMBAI Seven islands. Septuplets - seven unborn babies, waddling in a womb. A womb that we know more ordinarily as the Arabian Sea. Tied by a thin vestige of earth and rock – an umbilical cord of sorts – to the motherland. A kind mother. A cruel mother. A mother that has indulged as much as it has denied. A mother that has typically left the identity of the father in doubt. Like a whore. To speak of fathers who have fought for the right to sire: with each new pretender has come a new name. The babies have juggled many monikers, reflected in the schizophrenia the city seems to suffer from. -

Assessment of Agro-Tourism Potential in Junnar Tehsil, Maharashtra, India

Scholarly Research Journal for Interdisciplinary Studies, Online ISSN 2278-8808, SJIF 2016 = 6.17, www.srjis.com UGC Approved Sr. No.45269, SEPT-OCT 2017, VOL- 4/36 ASSESSMENT OF AGRO-TOURISM POTENTIAL IN JUNNAR TEHSIL, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA Thorat S. D.1 & Suryawanshi R.S.2 1PhD Research Student, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune-411007. E-mail - [email protected] 2Professor, Department of Geography, Abasaheb Garware College, Pune-411004, S.P.P.U. E-mail –[email protected] The present research paper is an attempt to analyse the level of development and potential of Agro- tourism in Junnar Tehsil in Pune District Maharashtra. Agro-tourism is the emerging branch of tourism in India. It helped for sustainable development in rural area. Agro-tourism give the opportunity to tourist to get aware with agricultural area, agricultural operations, local food and tradition of local area and support to economic development of farmers. The Junnar Tehsil in Pune district have many tourist destinations, but yet this Tehsil is not highlighted to large scale Agro- tourism practices. It is mainly because of lack of facilities and low development of area. The present research paper focuses on find out the potential area for agro-tourism in Junnar Tehsil. The development status of agro-tourism potential composite index is product of physiographic index and cropping pattern based on a GIS techniques. Keywords: Agro-Tourism, Composite Index and GIS technique. Scholarly Research Journal's is licensed Based on a work at www.srjis.com Introduction Tourism plays very important role in economic development on regional level. Now day’s tourism is one of the fastest growing industries in the world. -

Carzonrent Distance Grid (50Kms Radius)- Mumbai

CarzonRent Distance Grid (50kms Radius)- Mumbai. Disclaimer: Please note that the distances shown in the below Distance Grid Chart have been measured on the basis of specific locations of that particular area. For Example: Andheri East’s measurement (i.e. 4kms) is taken till the local railway station however; there is always a possibility of the actual pickup or drop off location of the Guest being beyond or within this measurement. Hence, the Guest’s total KMs travelled (One way) will be calculated on the basis of actual Odometer reading. Distance From International Airport-Mumbai ( Sr. No. Destination Oneway ) 1 Andheri East 4 2 Andheri West 8 3 Antop Hill 20 4 Altamount Rd 26 5 Annie Besant Rd 23.5 6 Anushakti Nagar 26 7 Ambassador Hotel 31 8 Byculla 28.5 9 Bandra East 13 10 Bandra West 16 11 Borivali East 16.5 12 Borivali West 19 13 Bhindi Bazaar 28.5 14 Bhandup 14 15 Breach Candy 26 16 Bombai Central 28.5 17 Bhulabai Desai Rd 31 18 Bhuleshwar 31 19 Bawas Hotel ( B,Central) 28.5 20 Bhayander 24 21 Bhiwandi 39 22 Chakala 2 23 Chembur 21 24 Churchgate 31 25 Chunnabhati 16 26 Colaba 36 27 Cumbala Hill 28.5 28 Carmicle Rd 28.5 29 Chira Bazaar 28.5 30 Charni Rd 28.5 31 Cheeta Champ 28.5 32 Crawford Market 31 33 Centaur Juhu 8 34 Cotton Green 28.5 35 Dadar 21 36 Dongri 25 37 Dhobi Talav 31 38 Dharavi 16 39 Dockyard Rd 28.5 40 Dahisar 19 1 of 4 CarzonRent Distance Grid (50kms Radius)- Mumbai. -

Mumbai-Marooned.Pdf

Glossary AAI Airports Authority of India IFEJ International Federation of ACS Additional Chief Secretary Environmental Journalists AGNI Action for good Governance and IITM Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology Networking in India ILS Instrument Landing System AIR All India Radio IMD Indian Meteorological Department ALM Advanced Locality Management ISRO Indian Space Research Organisation ANM Auxiliary Nurse/Midwife KEM King Edward Memorial Hospital BCS Bombay Catholic Sabha MCGM/B Municipal Council of Greater Mumbai/ BEST Brihan Mumbai Electric Supply & Bombay Transport Undertaking. MCMT Mohalla Committee Movement Trust. BEAG Bombay Environmental Action Group MDMC Mumbai Disaster Management Committee BJP Bharatiya Janata Party MDMP Mumbai Disaster Management Plan BKC Bandra Kurla Complex. MoEF Ministry of Environment and Forests BMC Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation MHADA Maharashtra Housing and Area BNHS Bombay Natural History Society Development Authority BRIMSTOSWAD BrihanMumbai Storm MLA Member of Legislative Assembly Water Drain Project MMR Mumbai Metropolitan Region BWSL Bandra Worli Sea Link MMRDA Mumbai Metropolitan Region CAT Conservation Action Trust Development Authority CBD Central Business District. MbPT Mumbai Port Trust CBO Community Based Organizations MTNL Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd. CCC Concerned Citizens’ Commission MSDP Mumbai Sewerage Disposal Project CEHAT Centre for Enquiry into Health and MSEB Maharashtra State Electricity Board Allied Themes MSRDC Maharashtra State Road Development CG Coast Guard Corporation -

District Census Handbook, Greater Bombay

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1981 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK GREATER BOMBAY Compiled by THE MAHARASHTRA CENSUS DIRECTORATE BOMBAY 1'1l00'ED IN INDIA. BY THE MANAGER, YERAVDA PRISON PllESS, pum AND pmLlSHED mY THE DIRECTOR, GOVERNlrfENT PRINTING AND STATIONEK.Y, :t4AHAIASHTltA STATE, BOMBAY 400 004, 1986 [ Price ; Rs. 30.00 ] MAHARASHTRA <slOISTRICT GREATER BOMBAY ..,..-i' 'r l;1 KM" LJIo_'=:::I0__ ";~<====:io4 ___~ KNS . / \ z i J I i I ! ~ .............. .~ • .--p;_.. _ • K¢'J· '- \ o BUTCHER ..~ ISLANO '.. , * o' J o Boundary ('i5lrict ,-.-._. __ .- ,,' / ,~. Nat:onal iiighway ",- /" State Highw«y ... SH i Railwuy line with station. Broad Gauge j Riwr and Stream ~ w. ter lea I urIs ~;::m I Degr.e College and lech.kat Institution Res! Hcu~e. Circwit Hou~. ( P. W. D.l RH. CH Poot and Jel.graph office PlO ~~';; ® Based "pon Surv~! af IIIifia mat> wlth 1M 1J@rm~ion. of l~" SUfVI!YlII' G~QI rJ! Ifda. Tile territorial waters 01 Indio ~d into Ihe sea to a dOslonce of twet.... n(llltic:ol milos meGsIlt'ell hllm tn& "PlllVp..-Qle ~G5e lin~. ~ MOTIF V. T. Station is a gateway to the 'Mumbai' where thousands of people come every day from different parts of India. Poor, rich, artist, industrialist. toumt alike 'Mumbainagari' is welcoming them since years by-gone. Once upon a time it was the mai,n centre for India's independence struggle. Today, it is recognised as the capital of India for industries and trade in view of its mammoth industrial complex and innumerable monetary transactions. It is. also a big centre of sports and culture. -

India Architecture Guide 2017

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Zone 1: Zanskar Geologically, the Zanskar Range is part of the Tethys Himalaya, an approximately 100-km-wide synclinorium. Buddhism regained its influence Lungnak Valley over Zanskar in the 8th century when Tibet was also converted to this ***** Zanskar Desert ཟངས་དཀར་ religion. Between the 10th and 11th centuries, two Royal Houses were founded in Zanskar, and the monasteries of Karsha and Phugtal were built. Don't miss the Phugtal Monastery in south-east Zanskar. Zone 2: Punjab Built in 1577 as the holiest Gurdwara of Sikhism. The fifth Sikh Guru, Golden Temple Rd, Guru Arjan, designed the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) to be built in Atta Mandi, Katra the centre of this holy tank. The construction of Harmandir Sahib was intended to build a place of worship for men and women from all walks *** Golden Temple Guru Ram Das Ahluwalia, Amritsar, Punjab 143006, India of life and all religions to come and worship God equally. The four entrances (representing the four directions) to get into the Harmandir ਹਰਿਮੰਦਿ ਸਾਰਹਬ Sahib also symbolise the openness of the Sikhs towards all people and religions. Mon-Sun (3-22) Near Qila Built in 2011 as a museum of Sikhism, a monotheistic religion originated Anandgarh Sahib, in the Punjab region. Sikhism emphasizes simran (meditation on the Sri Dasmesh words of the Guru Granth Sahib), that can be expressed musically *** Virasat-e-Khalsa Moshe Safdie Academy Road through kirtan or internally through Nam Japo (repeat God's name) as ਰਿਿਾਸਤ-ਏ-ਖਾਲਸਾ a means to feel God's presence. -

Reliance Foundation and Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai to Provide Three Lakh Free COVID-19 Vaccines for Mumbai’S Underprivileged Communities

MEDIA RELEASE Reliance Foundation and Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai to provide three lakh free COVID-19 vaccines for Mumbai’s underprivileged communities • Communities across 50 locations including Dharavi, Worli, Wadala, Colaba, Kamatipura, Chembur to be covered • Reliance Foundation through Sir H N Reliance Foundation Hospital is deploying state-of-the-art mobile vehicle unit for the vaccination drive • Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) and BEST provide infrastructure & logistics support Mumbai, 2nd August 2021: In a major outreach scheme to protect Mumbai’s vulnerable communities, Reliance Foundation through Sir H N Reliance Foundation Hospital will collaborate with Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) to provide three lakh COVID-19 vaccination doses to communities across 50 locations in Mumbai. This free vaccination drive aims to protect underprivileged people in neighbourhoods including Dharavi, Worli, Wadala, Colaba, Pratiksha Nagar, Kamatipura, Mankhurd, Chembur, Govandi and Bhandup. Sir H N Reliance Foundation Hospital is deploying a state-of-the-art mobile vehicle unit to conduct the vaccination drive across the selected locations of Mumbai, while MCGM and BEST will provide infrastructure and logistics support for the drive. This initiative builds on Sir HN Reliance Foundation Hospital’s regular health outreach initiatives in Mumbai, which address primary and preventive healthcare needs of vulnerable populations through mobile medical vans and static medical units. This vaccination programme will be carried out over the next three months and is part of Reliance Foundation’s Mission Vaccine Suraksha initiative which will also provide vaccination for underprivileged communities around the country over the next few months. Smt Nita M Ambani, Founder and Chairperson, Reliance Foundation said: “Reliance Foundation has stood by the nation at every step of this relentless fight against the COVID- 19 pandemic. -

NAGAR's Newsletter, 2016-2017

Refuse T D R P O B D T NAGAR Newsletter April 2016-March 2017 Solid Waste Management Quality of Air Public Open Spaces Water BodiesBetter Policing Water Conservation Road Space Management Historic Built/Natural Heritage Public Open Spaces NAGAR continued to urge the MCGM to follow Best Practices for maintaining all Public Open Spaces owned by them. To emphasize the importance of this, NAGAR chose W.I.T. ground, a neglected public open space designated as a playground, located in Mahim. NAGAR has prepared the design to restore the character of the playground to showcase an ideal plan and will share this with MCGM for implementation. PANORAMIC VIEW OF W.I.T. GROUND, MAHIM COURTESY: NAGAR NAGAR strongly objected to MCGM’s interim policy on public open spaces, that was passed hurriedly before the end of the tenure of the then elected body and days before the restrictions imposed under the election code of conduct. The Policy facilitated an unacceptable option to private organisations, NGOs and citizen groups to enable them to retain their hold over the 216 public open spaces that were to be taken back from them under the orders of the Chief Minister Mr. Devendra Fadnavis. CROSS MAIDAN CROSS MAIDAN COURTESY: flickr (Ninad Chaudhari) COURTESY: NUDES (Artist Studio of the Sculpture, called Charkha) 1 Solid Waste Management Quality of Air Public Open Spaces Water BodiesBetter Policing Water Conservation Road Space Management Historic Built/Natural Heritage Public Open Spaces NAGAR wrote a letter to the Chief Minister, Mr. Devendra Fadnavis objecting to the construction of a ‘Theme Park’ on the Mahalaxmi racecourse land. -

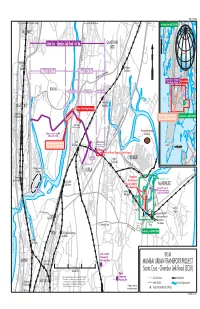

Chembur Link Road (SCLR) Matunga to Mumbai Rail Station This Map Was Produced by the Map Design Unit of the World Bank

IBRD 33539R To Jogeswari-Virkhroli Link Road / Borivali To Jogeswari-Virkhroli Link Road To Thane To Thane For Detail, See IBRD 33538R VILE PARLE ek re GHATKOPAR C i r Santa Cruz - Chembur Link Road: 6.4 km o n a SATIS M Mumbai THANE (Kurla-Andhai Road) Vile Parle ek re S. Mathuradas Vasanji Marg C Rail alad Station Ghatkopar M Y Rail Station N A Phase II: 3.0 km Phase I: 3.4 km TER SW S ES A E PR X Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg WESTERN EXPRESSWAY E Santa Cruz - Chembur Link Road: 6.4 km Area of Map KALINA Section 1: 1.25 km Section 2: 1.55 km Section 3: .6 km ARABIAN Swami Vivekananda Marg SEA Vidya Vihar Thane Creek SANTA CRUZ Rail Station Area of Gazi Nagar Request Mahim Bay Santa Cruz Rail Station Area of Shopkeepers' Request For Detail, See IBRD 33540R For Detail, See IBRD 33314R MIG Colony* (Middle Income Group) Central Railway Deonar Dumping 500m west of river and Ground 200m south of SCLR Eastern Expressway R. Chemburkar Marg Area of Shopkeepers' Request Kurla MHADA Colony* CHURCHGATE CST (Maharashtra Housing MUMBAI 012345 For Detail, See IBRD 33314R Rail Station and Area Development Authority) KILOMETERS Western Expressway Area of Bharathi Nagar Association Request S.G. Barve Marg (East) Gha Uran Section 2 Chembur tko CHEMBUR Rail Station parM ankh urdLink Bandra-Kurla R Mithi River oad To Vashi Complex KURLA nar Nala Deo Permanent Bandra Coastal Regulation Zones Rail Station Chuna Batti Resettlement Rail Station Housing Complex MANKHURD at Mankhurd Occupied Permanent MMRDA Resettlement Housing Offices Govandi Complex at Mankhurd Rail Station Deonar Village Road Mandala Deonarpada l anve Village P Integrated Bus Rail Sion Agarwadi Interchange Terminal Rail Station Mankhurd Mankhurd Correction ombay Rail Station R. -

Redharavi1.Pdf

Acknowledgements This document has emerged from a partnership of disparate groups of concerned individuals and organizations who have been engaged with the issue of exploring sustainable housing solutions in the city of Mumbai. The Kamala Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute of Architecture (KRVIA), which has compiled this document, contributed its professional expertise to a collaborative endeavour with Society for Promotion of Area Resource Centres (SPARC), an NGO involved with urban poverty. The discussion is an attempt to create a new language of sustainable urbanism and architecture for this metropolis. Thanks to the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP) authorities for sharing all the drawings and information related to Dharavi. This project has been actively guided and supported by members of the National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF) and Dharavi Bachao Andolan: especially Jockin, John, Anand, Savita, Anjali, Raju Korde and residents’ associations who helped with on-site documentation and data collection, and also participated in the design process by giving regular inputs. The project has evolved in stages during which different teams of researchers have contributed. Researchers and professionals of KRVIA’s Design Cell who worked on the Dharavi Redevelopment Project were Deepti Talpade, Ninad Pandit and Namrata Kapoor, in the first phase; Aditya Sawant and Namrata Rao in the second phase; and Sujay Kumarji, Kairavi Dua and Bindi Vasavada in the third phase. Thanks to all of them. We express our gratitude to Sweden’s Royal University College of Fine Arts, Stockholm, (DHARAVI: Documenting Informalities ) and Kalpana Sharma (Rediscovering Dharavi ) as also Sundar Burra and Shirish Patel for permitting the use of their writings.