Rotation and Magnetic Activity of the Hertzsprung-Gap Giant 31 Comae�,

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

The Dynamical State of the Coma Cluster with XMM-Newton?

A&A 400, 811–821 (2003) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20021911 & c ESO 2003 Astrophysics The dynamical state of the Coma cluster with XMM-Newton? D. M. Neumann1,D.H.Lumb2,G.W.Pratt1, and U. G. Briel3 1 CEA/DSM/DAPNIA Saclay, Service d’Astrophysique, L’Orme des Merisiers, Bˆat. 709, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France 2 Science Payloads Technology Division, Research and Science Support Dept., ESTEC, Postbus 299 Keplerlaan 1, 2200AG Noordwijk, The Netherlands 3 Max-Planck Institut f¨ur extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstr., 85740 Garching, Germany Received 19 June 2002 / Accepted 13 December 2002 Abstract. We present in this paper a substructure and spectroimaging study of the Coma cluster of galaxies based on XMM- Newton data. XMM-Newton performed a mosaic of observations of Coma to ensure a large coverage of the cluster. We add the different pointings together and fit elliptical beta-models to the data. We subtract the cluster models from the data and look for residuals, which can be interpreted as substructure. We find several significant structures: the well-known subgroup connected to NGC 4839 in the South-West of the cluster, and another substructure located between NGC 4839 and the centre of the Coma cluster. Constructing a hardness ratio image, which can be used as a temperature map, we see that in front of this new structure the temperature is significantly increased (higher or equal 10 keV). We interpret this temperature enhancement as the result of heating as this structure falls onto the Coma cluster. We furthermore reconfirm the filament-like structure South-East of the cluster centre. -

WASP Page 1 Hubble Eyes Aging Stars Science News, Vol. 148

WASP Warren Astronomical Society Paper Volume 27, number 11 $1.00 for non-members November 1995 DATING THE COSMOS COMPUTER CHATTER ANNUAL HOLIDAY AWARDS Hubble eyes aging stars Larry F. Kalinowski Science News, Vol. 148, September 2,1995 submitted by Lorna Simmons Everyone knows you can't be older than your mother. But over the past year, observations with the Hubble Space Telescope and several other Comet DeVico has just passed perihelion in instruments seem to have contradicted this cardi- early October, so its beginning to fade from its maxi- nal rule. On the one hand, measurements of the mum brightness of 5.6. It was recovered in its seventy- speed at which the most distant galaxies are mov- four year orbit by independent comet observers Naka- ing from Earth suggest that the universe may be mura, Tanaka and Utsunomiya. It becomes a sixth no older than 8 billion to 12 billion years (SN: magnitude object on the night of the Macomb meeting, 10/8;94, p.232). On the other hand, astronomers October 19. Early reports say it has two tails. A morn- ing object, only, about fifteen degrees above the hori- estimate he ages of our galaxy's oldest stars at zon before twilight begins, it's easily observed as it 13 billion to 16 billion years. leaves Leo and enters the Ursa Major-Coma Berenices Now, new findings from Hubble may provide a area of the sky. However, it is quickly moving closer to step toward resolving this cosmic conundrum. the horizon and will become increasingly more difficult In viewing the globular cluster M4, the dense to observe during the rest of the month. -

Astroph0807.3345 Ful

Draft version July 22, 2008 A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 08/13/06 THE INVISIBLES: A DETECTION ALGORITHM TO TRACE THE FAINTEST MILKY WAY SATELLITES S. M. Walsh1, B. Willman2, H. Jerjen1 Draft version July 22, 2008 ABSTRACT A specialized data mining algorithm has been developed using wide-field photometry catalogues, en- abling systematic and efficient searches for resolved, extremely low surface brightness satellite galaxies in the halo of the Milky Way (MW). Tested and calibrated with the Sloan Digital Sky Survey Data Release 6 (SDSS-DR6) we recover all fifteen MW satellites recently detected in SDSS, six known MW/Local Group dSphs in the SDSS footprint, and 19 previously known globular and open clusters. In addition, 30 point source overdensities have been found that correspond to no cataloged objects. The detection efficiencies of the algorithm have been carefully quantified by simulating more than three million model satellites embedded in star fields typical of those observed in SDSS, covering a wide range of parameters including galaxy distance, scale-length, luminosity, and Galactic latitude. We present several parameterizations of these detection limits to facilitate comparison between the observed Milky Way satellite population and predictions. We find that all known satellites would be detected with > 90% efficiency over all latitudes spanned by DR6 and that the MW satellite census within DR6 is complete to a magnitude limit of MV ≈−6.5 and a distance of 300 kpc. Assuming all existing MW satellites contain an appreciable old stellar population and have sizes and luminosities comparable to currently known companions, we predict a lower limit total of 52 Milky Way dwarf satellites within ∼ 260 kpc if they are uniformly distributed across the sky. -

From Messier to Abell: 200 Years of Science with Galaxy Clusters

Constructing the Universe with Clusters of Galaxies, IAP 2000 meeting, Paris (France) July 2000 Florence Durret & Daniel Gerbal eds. FROM MESSIER TO ABELL: 200 YEARS OF SCIENCE WITH GALAXY CLUSTERS Andrea BIVIANO Osservatorio Astronomico di Trieste via G.B. Tiepolo 11 – I-34131 Trieste, Italy [email protected] 1 Introduction The history of the scientific investigation of galaxy clusters starts with the XVIII century, when Charles Messier and F. Wilhelm Herschel independently produced the first catalogues of nebulæ, and noticed remarkable concentrations of nebulæ on the sky. Many astronomers of the XIX and early XX century investigated the distribution of nebulæ in order to understand their relation to the local “sidereal system”, the Milky Way. The question they were trying to answer was whether or not the nebulæ are external to our own galaxy. The answer came at the beginning of the XX century, mainly through the works of V.M. Slipher and E. Hubble (see, e.g., Smith424). The extragalactic nature of nebulæ being established, astronomers started to consider clus- ters of galaxies as physical systems. The issue of how clusters form attracted the attention of K. Lundmark287 as early as in 1927. Six years later, F. Zwicky512 first estimated the mass of a galaxy cluster, thus establishing the need for dark matter. The role of clusters as laboratories for studying the evolution of galaxies was also soon realized (notably with the collisional stripping theory of Spitzer & Baade430). In the 50’s the investigation of galaxy clusters started to cover all aspects, from the distri- bution and properties of galaxies in clusters, to the existence of sub- and super-clustering, from the origin and evolution of clusters, to their dynamical status, and the nature of dark matter (or “positive energy”, see e.g., Ambartsumian29). -

Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram and Mass Distribution of Barium Stars ? A

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. HRD_Ba c ESO 2019 May 14, 2019 Hertzsprung-Russell diagram and mass distribution of barium stars ? A. Escorza1; 2, H.M.J. Boffin3, A.Jorissen2, S. Van Eck2, L. Siess2, H. Van Winckel1, D. Karinkuzhi2, S. Shetye2; 1, and D. Pourbaix2 1 Institute of Astronomy, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium 2 Institut d’Astronomie et d’Astrophysique, Université Libre de Bruxelles, ULB, Campus Plaine C.P. 226, Boulevard du Triomphe, B-1050 Bruxelles, Belgium 3 ESO, Karl Schwarzschild Straße 2, D-85748 Garching bei München, Germany Received; Accepted ABSTRACT With the availability of parallaxes provided by the Tycho-Gaia Astrometric Solution, it is possible to construct the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram (HRD) of barium and related stars with unprecedented accuracy. A direct result from the derived HRD is that subgiant CH stars occupy the same region as barium dwarfs, contrary to what their designations imply. By comparing the position of barium stars in the HRD with STAREVOL evolutionary tracks, it is possible to evaluate their masses, provided the metallicity is known. We used an average metallicity [Fe/H] = −0.25 and derived the mass distribution of barium giants. The distribution peaks around 2.5 M with a tail at higher masses up to 4.5 M . This peak is also seen in the mass distribution of a sample of normal K and M giants used for comparison and is associated with stars located in the red clump. When we compare these mass distributions, we see a deficit of low-mass (1 – 2 M ) barium giants. -

Module 14 H. R. Diagram TABLE of CONTENTS 1. Learning Outcomes

Module 14 H. R. Diagram TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Learning Outcomes 2. Introduction 3. H. R. Diagram 3.1. Coordinates of H. R. Diagram 3.2. Stellar Families 3.3. Hertzsprung Gap 3.4. H. R. Diagram and Stellar Radii 4. Summary 1. Learning Outcomes After studying this module, you should be able to recognize an H. R. Diagram explain the coordinates of an H. R. Diagram appreciate the shape of an H. R. Diagram understand that in this diagram stars appear in distinct families recount the characteristics of these families recognize that there is a real gap in the horizontal branch of the diagram, called the Hertzsprung gap explain that during their evolution stars pass very rapidly through this region and therefore there is a real paucity of stars here derive the shape of the 퐥퐨퐠 푻 − 퐥퐨퐠 푳 plot at a given stellar radius explain that the stellar radius (and mass) increases upwards in the H. R. Diagram 2. Introduction In the last few modules we have discussed the stellar spectra and spectral classification based on stellar spectra. The Harvard system of spectral classification categorized stellar spectra in 7 major classes, from simple spectra containing only a few lines to spectra containing a huge number of lines and molecular bands. The major classes were named O, B, A, F, G, K and M. Each major class was further subdivided into 10 subclasses, running from 0 to 9. Considering the bewildering variety of stellar spectra, classes Q, P and Wolf-Rayet had to be introduced at the top of the classification and classes R and N were introduced at the bottom of the classification scheme. -

Coma Cluster of Galaxies

Coma Cluster of Galaxies In 2006, Hubble Space Telescope aimed at a nearby collection of NATIONAL SCIENCE EDUCATION STA N D A R D S galaxies called the Coma Cluster. Using the HST images, astronomers • Content Standard in 9-12 Science as gained fascinating insights into the evolution of galaxies in dense Inquiry (Abilities necessary to do sci- galactic neighborhoods. In this activity, students will first learn the entific inquiry, Understanding about basics of galaxy classification and grouping, then use HST images to scientific inquiry) discover the “morphology-density effect” and make hypotheses about • Content Standard in 9-12 Earth and its causes. Space Science (Origin and evolution of the universe) MATERIALS & PRE PARATION • Each student needs a copy of the next 7 pages (not this page). You may InvIsIble Clu s t e r copy the pages out of this guide, but it is recommended that you go to If you aim a big telescope at the Coma mcdonaldobservatory.org/teachers/classroom and download the student Cluster, you’ll see galaxies galore worksheets. The galaxy images in the online worksheets are “negatives” — thousands of galaxies of all sizes of the real images, which provides better detail when printing. Supple- and shapes, from little puffballs to mental materials for this activity are also available on the website. big, fuzzy footballs. Even so, you won’t • Each student or student team will need a calculator and a magnifying see most of the cluster because it’s invis- glass (a linen tester works well). ible to human eyes. • Knowledge of percentages is needed before doing this activity. -

Structure and Evolution of FK Comae Corona

A&A 383, 919–932 (2002) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20011810 & c ESO 2002 Astrophysics Structure and evolution of FK Comae corona P. Gondoin, C. Erd, and D. Lumb Space Science Department, European Space Agency – Postbus 299, 2200 AG Noordwijk, The Netherlands Received 16 October 2001 / Accepted 17 December 2001 Abstract. FK Comae (HD 117555) is a rapidly rotating single G giant whose distinctive characteristics include a quasisinusoidal optical light curve and high X-ray luminosity. FK Comae was observed twice at two weeks interval in January 2001 by the XMM-Newton space observatory. Analysis results suggest a scenario where the corona of FK Comae is dominated by large magnetic structures similar in size to interconnecting loops between solar active regions but significantly hotter. The interaction of these structures themselves could explain the permanent flaring activity on large scales that is responsible for heating FK Comae plasma to high temperatures. During our observations, these flares were not randomly distributed on the star surface but were partly grouped within a large compact region of about 30 degree extent in longitude reminiscent of a large photospheric spot. We argue that the α − Ω dynamo driven activity on FK Comae will disappear in the future with the effect of suppressing large scale magnetic structures in its corona. Key words. stars: individual: FK Comae – stars: activity – stars: coronae – stars: evolution – stars: late-type – X-ray: stars 1. Introduction ments and their temporal behaviour during the observa- tions. Sections 5 and 6 describe the spectral analysis of the FK Comae (HD 117555) is the prototype of a small group EPIC and RGS datasets. -

Biennial Report 2006 2007 Published in Spain by the Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes (ING) ISSN 1575–8966 Legal License: TF–1142 /99

I SAAC N EWTON G ROUP OF T ELESCOPES Biennial Report 2006 2007 Published in Spain by the Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes (ING) ISSN 1575–8966 Legal license: TF–1142 /99 Apartado de correos, 321 E-38700 Santa Cruz de La Palma; Canary Islands; Spain Tel: +34 922 425 400 Fax: +34 922 425 401 URL: http://www.ing.iac.es/ Editor and designer: Javier Méndez ([email protected]) Printing: Gráficas Sabater. Tel: +34 922 623 555 Front cover: The Milky Way from the site of the William Herschel Telescope. Credit: Nik Szymanek. Inset: Photograph of the WHT at sunset. Credit: Nik Szymanek. Other picture credits: Nik Szymanek (WHT, p. 4; INT, p. 4; JKT, p. 4; ING, p. 5); Jens Moser (WHT, back; INT, back); Nik Szymanek (JKT, back). The ING Biennial Report is available online at http://www.ing.iac.es/PR/AR/. ISAAC NEWTON GROUP OF TELESCOPES Biennial Report of the STFC-NWO-IAC ING Board 2006 – 2007 ISAAC NEWTON GROUP William Herschel Telescope Isaac Newton Telescope Jacobus Kapteyn Telescope 4 • ING BIENNIAL R EPORT 2006–2007 OF TELESCOPES The Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes (ING) consists of the 4.2- metre William Herschel Telescope (WHT), the 2.5-metre Isaac Newton Telescope (INT) and the 1.0-metre Jacobus Kapteyn Telescope (JKT). The ING is located 2350 metres above sea level at the Observatorio del Roque de los Muchachos (ORM) on the island of La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain. The WHT is the largest telescope of its kind in Western Europe. The construction, operation, and development of the ING telescopes are the result of a collaboration between the United Kingdom, The Netherlands and Spain. -

Astronomy 113 Laboratory Manual

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN - MADISON Department of Astronomy Astronomy 113 Laboratory Manual Fall 2011 Professor: Snezana Stanimirovic 4514 Sterling Hall [email protected] TA: Natalie Gosnell 6283B Chamberlin Hall [email protected] 1 2 Contents Introduction 1 Celestial Rhythms: An Introduction to the Sky 2 The Moons of Jupiter 3 Telescopes 4 The Distances to the Stars 5 The Sun 6 Spectral Classification 7 The Universe circa 1900 8 The Expansion of the Universe 3 ASTRONOMY 113 Laboratory Introduction Astronomy 113 is a hands-on tour of the visible universe through computer simulated and experimental exploration. During the 14 lab sessions, we will encounter objects located in our own solar system, stars filling the Milky Way, and objects located much further away in the far reaches of space. Astronomy is an observational science, as opposed to most of the rest of physics, which is experimental in nature. Astronomers cannot create a star in the lab and study it, walk around it, change it, or explode it. Astronomers can only observe the sky as it is, and from their observations deduce models of the universe and its contents. They cannot ever repeat the same experiment twice with exactly the same parameters and conditions. Remember this as the universe is laid out before you in Astronomy 113 – the story always begins with only points of light in the sky. From this perspective, our understanding of the universe is truly one of the greatest intellectual challenges and achievements of mankind. The exploration of the universe is also a lot of fun, an experience that is largely missed sitting in a lecture hall or doing homework. -

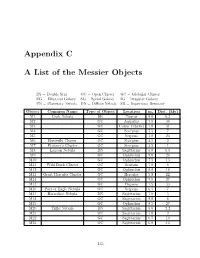

Appendix C a List of the Messier Objects

Appendix C A List of the Messier Objects DS=DoubleStar OC=OpenCluster GC=GlobularCluster EG = Elliptical Galaxy SG = Spiral Galaxy IG = Irregular Galaxy PN = Planetary Nebula DN = Diffuse Nebula SR = Supernova Remnant Object Common Name Type of Object Location mv Dist. (kly) M1 Crab Nebula SR Taurus 9.0 6.3 M2 GC Aquarius 7.5 36 M3 GC Canes Venatici 7.0 31 M4 GC Scorpius 7.5 7 M5 GC Serpens 7.0 23 M6 Butterfly Cluster OC Scorpius 4.5 2 M7 Ptolemy’s Cluster OC Scorpius 3.5 1 M8 Lagoon Nebula DN Sagittarius 5.0 6.5 M9 GC Ophiuchus 9.0 26 M10 GC Ophiuchus 7.5 13 M11 Wild Duck Cluster OC Scutum 7.0 6 M12 GC Ophiuchus 8.0 18 M13 Great Hercules Cluster GC Hercules 5.8 22 M14 GC Ophiuchus 9.5 27 M15 GC Pegasus 7.5 33 M16 Part of Eagle Nebula OC Serpens 6.5 7 M17 Horseshoe Nebula DN Sagittarius 7.0 5 M18 OC Sagittarius 8.0 6 M19 GC Ophiuchus 8.5 27 M20 Trifid Nebula DN Sagittarius 5.0 2.2 M21 OC Sagittarius 7.0 3 M22 GC Sagittarius 6.5 10 M23 OC Sagittarius 6.0 4.5 135 Object Common Name Type of Object Location mv Dist. (kly) M24 Milky Way Patch Star cloud Sagittarius 11.5 10 M25 OC Sagittarius 4.9 2 M26 OC Scutum 9.5 5 M27 Dumbbell Nebula PN Vulpecula 7.5 1.25 M28 GC Sagittarius 8.5 18 M29 OC Cygnus 9.0 7.2 M30 GC Capricornus 8.5 25 M31 Andromeda Galaxy SG Andromeda 3.5 2500 M32 Satellite galaxy of M31 EG Andromeda 10.0 2900 M33 Triangulum Galaxy SG Triangulum 7.0 2590 M34 OC Perseus 6.0 1.4 M35 OC Gemini 5.5 2.8 M36 OC Auriga 6.5 4.1 M37 OC Auriga 6.0 4.6 M38 OC Auriga 7.0 4.2 M39 OC Cygnus 5.5 0.3 M40 Winnecke 4 DS Ursa Major 9.0 M41 OC Canis