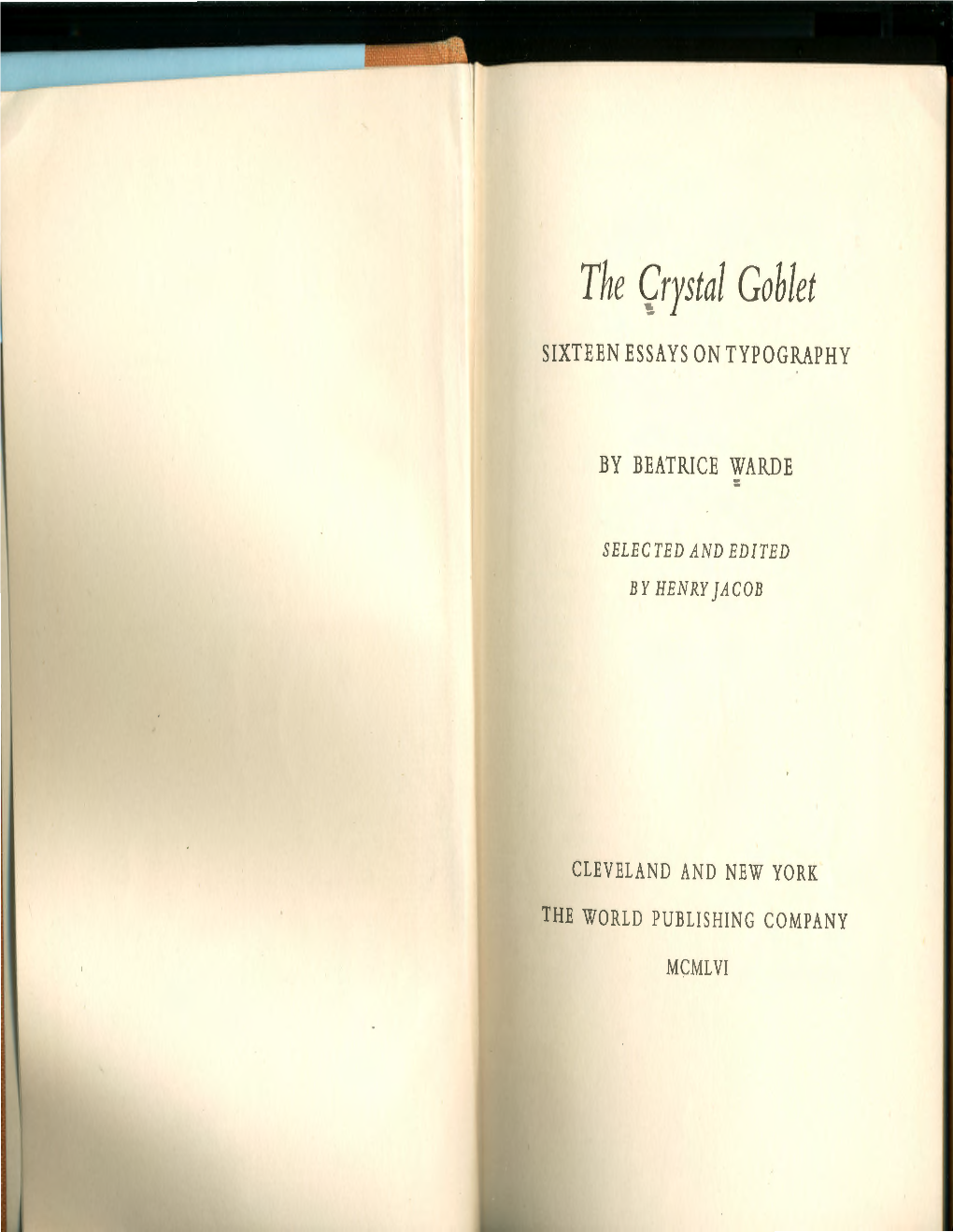

The Crystal Goblet, Or Printing Should Be Invisible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Press of A. Colish Archives

Special Collections Department The Press of A. Colish Archives 1913 - 1990 (bulk dates 1930s - 1950s) Manuscript Collection Number: 358 Accessioned: Purchase, September 1991. Extent: 5 linear ft. plus oversize material Content: Correspondence, galley and page proofs, drafts, notes, photographs, negatives, illustrations, advertisements, clippings, broadsides, books, chapbooks, pamphlets, journals, typography specimens, financial documents, and ephemera. Access: The collection is open for research. Processed: March 1998, by Shanon Lawson for reference assistance email Special Collections or contact: Special Collections, University of Delaware Library Newark, Delaware 19717-5267 (302) 831-2229 Table of Contents Biographical and Historical Note Scope and Contents Note Series Outline Contents List Biographical and Historical Note American fine printer and publisher Abraham Colish (1882-1963) immigrated with his family to the United States from Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth century. In 1894, at the age of twelve, he took an after-school job with a small printing shop in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Over the next few years, his duties progressed from sweeping the shop and selling papers to feeding the press and composing type. When he was sixteen, Colish and his mother moved to New York City, where he quickly found a position as a typesetter for Kane Brothers, a Broadway printing company. In 1907, Colish left his position as a composing room foreman at Rogers and Company and opened his own composing office. His business specialized in advertising typography and is credited as the first shop to exclusively cater to the advertising market. By the next year, Colish moved into larger quarters and began printing small orders. After several moves to successively larger offices in New York City, the Press of A. -

ERIC GILL SAGGIO an Essay SULLA on TIPO Typography GRAFIA

ERIC GILL SAGGIO An Essay SULLA on TIPO Typography GRAFIA RONZANI EDITORE typographica storia e culture del libro 2 Eric Gill, foto di Howard Coster, 1928 ERIC GILL Saggio sulla tipografia Ronzani Editore Eric gill, Saggio Sulla tipografia Titolo originale: An Essay on Typography Traduzione di Lucio Passerini Seconda edizione italiana interamente riveduta dall’editore con il testo originale inglese © 2019 Ronzani Editore S.r.l. | Tutti i diritti riservati www.ronzanieditore.it | [email protected] ISBN 978-88-94911-15-2 SOMMARIO Introduzione, di Lucio Passerini 7 Saggio sulla tipografia 23 Il Tema 25 1. Composizione del tempo e del luogo 29 2. Disegno delle lettere 45 3. Tipografia 77 4. Incisione dei punzoni 89 5. Carta e inchiostro 93 6. Il letto di Procuste 99 7. Lo strumento 105 8. Il libro 111 9. Perché le lettere ? 123 An Essay on Typography 135 INTRODUZIONE di Lucio Passerini La prima edizione di questo saggio di Eric Gill fu eseguita sotto il diretto controllo dell’autore. Composta nel 1931, venne stampata in 500 copie firmate, su carta apposita- mente fabbricata a mano, nella tipografia che lo stesso Gill aveva impiantato l’anno precedente insieme al gene- ro René Hague presso la casa in cui risiedeva. Il libro fu composto con un nuovo carattere disegnato apposita- mente da Gill per questa impresa editoriale di famiglia, inciso e fuso per la composizione a mano dalla Caslon Letter Foundry di Londra. Il carattere venne chiamato Joanna, come la figlia di Gill, moglie di René Hague. Pubblicato a Londra da Sheed & Ward, il volume portava sulla sovraccoperta la dicitura « Printing & Piety. -

Printmaking Through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012

Printmaking through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012 Table of Contents Page Contents 2 Image List 3 Printmaking as Art 6 Glossary of Printing Terms 7 A Brief History of Printmaking Written by Jennifer Jensen 10 Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap , Rembrandt Written by Hailey Leek 11 Lesson Plan for Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap Written by Virginia Catherall 14 Kintai Bridge, Province of Suwo, Hokusai Written by Jennifer Jensen 16 Lesson Plan for Kintai Bridge, Province of Suwo Written by Jennifer Jensen 20 Lambing , Leighton Written by Kathryn Dennett 21 Lesson Plan for Lambing Written by Kathryn Dennett 32 Madame Louison, Rouault Written by Tiya Karaus 35 Lesson Plan for Madame Louison Written by Tiya Karaus 41 Prodigal Son , Benton Written by Joanna Walden 42 Lesson Plan for Prodigal Son Written by Joanna Walden 47 Flotsam, Gottlieb Written by Joanna Walden 48 Lesson Plan for Flotsam Written by Joanna Walden 55 Fourth of July Still Life, Flack Written by Susan Price 57 Lesson Plan for Fourth of July Still Life Written by Susan Price 59 Reverberations, Katz Written by Jennie LaFortune 60 Lesson Plan for Reverberations Written by Jennie LaFortune Evening for Educators is funded in part by the StateWide Art Partnership and the Professional Outreach Programs in the Schools (POPS) through the Utah State Office of Education 1 Printmaking through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012 Image List 1. Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606-1669), Dutch Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap with Plume , 1638 Etching Gift of Merrilee and Howard Douglas Clark 1996.47.1 2. -

141 18 Survey 3 Block Books and Baroque 1450-1750.Key

Survey 2 quiz God and Gutenberg (0-1450 CE) 2 What were early books written on before paper making techniques spread from Asia? (ca. 100-400) Thousands of years ago the Ancient Egyptians used papyrus as a writing surface for their scrolls. The Egyptians, and other civilizations also used animal skins to write on. These scraped animal skins used for writing are known as A: Parchment What do we call the fine parchment made from lamb or calf-skin that was used for very expensive books? A: Vellum One of the great qualities of parchment was that it was more opaque than papyrus, so both sides could be used for writing. More (not part of the quiz, just recapping): This membrane, made most often of sheep, or goatskin, was more opaque than papyrus, allowing scribes to write on both sides. The skins were scraped, stretched and dried (similar to the skin on a first nations drum). High quality parchment, made from calfskin, was called vellum. Unlike papyrus, this more supple material was easily folded and bound. Gradually manuscripts transitioned from scrolls to codices (singular codex): a term used to describe any ancient manuscript text in book form. These were bound books as we know them today, with folded sheets, stitched and glued along the spine. It is said that the parchment trade developed from Pergamon (now in Turkey). The city certainly became a huge production centre. Legend has it that king Ptolemy of Egypt banned papyrus export to Pergamon, in fear that the library of king Eumenes II of Pergamon would surpass his library in Alexandria. -

The Rose of Sharon Block Book Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE ROSE OF SHARON BLOCK BOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sharon Pederson | 96 pages | 01 Oct 2010 | Martingale & Company | 9781604680119 | English | Woodinville, United States The Rose of Sharon Block Book PDF Book You can read how we use cookies in our privacy policy. Write a review. New Softcover Quantity Available: 1. Sign in. Friendship Quilters added it Aug 30, Toryn Green added it Oct 21, I really enjoy this one. Other editions. Wcplanfi added it Sep 17, Recommend this product to a friend If you know someone who you think may be interested in this product, let them know below Proceeds from the book go to the Alzheimer's Art Quilt Initiative. Connect with Us. Quick view. All Crochet ePatterns. Aren't they beautiful? Sharon received over blocks, from which judges Alex Andersen and Ricky Tims selected 12 winners. Julie Glowney rated it really liked it Aug 01, Error rating book. You might also like I love simple pieced blocks, but I had to know more about these blocks! Enlarge cover. No right or wrong way, just your way. About the Author : Sharon Pederson is a best-selling author who has taught hundreds of quiltmaking classes, both nationally and internationally. Ann Johnson added it May 28, I only made one table runner using this method, and it was great to see how you can use it even on quilts with sashing and borders. Paperback , 96 pages. This site uses cookies. Dawn Hand rated it really liked it Nov 23, Orders Wish list Check order status. Discover more than 60 additional blocks from the Rose of Sharon challenge entries Find complete instructions for machine applique and quilt assembly View alternate settings and explore even more design possibilities. -

Printmaking – Woodcut Design Name:______

PRINTMAKING – WOODCUT DESIGN NAME:___________ Woodcut and wood engraving, prints are made from designs cut in relief on wood (subtractive process), in contrast to copper or steel engraving and etching (which are intaglio). Woodcuts are relief prints. The design is drawn on the surface of a wooden block or plank. The areas that are to be blank are cut away, leaving raised the design that is to be printed. Ink is then rolled or daubed over the raised area. A sheet of paper is placed on top of the block and pressed against it, either in a press or by hand. This pressure transfers the ink to the paper. Since the print is the mirror image of the design on the block, the image must be conceived in reverse. A rubber stamp is a common example of a relief printing process. Woodcutting, the oldest method of printmaking, is accomplished using soft wood with a knife employed along the grain. Concert Poster Design STEP ONE: Decide on one of the following choices for your woodcut design: • Poster Advertisement (Upcoming Performance) • Portrait: Human or Animal • Landscape (Look at reverse for art history of woodcuts) STEP TWO: Begin by making a series of at least 3 conceptual sketches in your sketchbook on your chosen theme. CONSIDER: Positive/negative space, contrast, line and overall composition. STEP THREE: Drawing the reverse outline of your subject matter on the flat top of the piece of wood. REMEMBER: to draw the outline of any text backwards as the print will print front wards. Carefully consider how you design your positive/negative space. -

The Story of Perpetua

The Story of Perpetua 3 Tiffany Wardle March 10, 2000 2 4 Essay submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Theory and History of Typography and Graphic Communication, University of Reading, 2000. This essay relates the origins of the typeface Perpetua and Felicity italic which were designed by Eric Gill and produced byThe Monotype Corporation.Although the type and the collaborators are well known, the story has had to be pieced together from a variety of sources—Gill’s and Morison’s own writings and biographical accounts.There are accounts similar to this, but none could be found that either takes this point of view, or goes into as great detail. In 1924, an essay directed towards the printers and type founders was calling for a new type for their time. Entitled ‘Towards An Ideal Type,’ Stanley Morison wrote it for the second volume of The Fleuron. In the closing statement there is an appeal for “some modern designer who knows his way along the old paths to fashion a fount of maximum homogeneity, that is to say, a type in which the uppercase, in spite of its much greater angularity and rigidity, accords with the great fellowship of colour and form with the rounder and more vivacious lowercase.”1 Two years later, in 1926, again Morison is requesting a “typography based not upon the needs and conventions of renaissance society but upon those of modern England.”2 Only two years previous had the Monotype Corporation assigned Stanley Morison as their Typographical Advisor. Once assigned he pursued what he later came to call his “programme of typographical design”3 with renewed vigour. -

The Illustrated Book Cover Illustrations

THE ILLUSTRATED BOOK COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: A collection of 18 pronouncements by Buddhist sages accompanied by their pictures. n.p., n.d. Manuscript scroll folded into 42 pages, written on leaves of the bodhi tree. Chinese text, beginning with the date wu-shu of Tao kuang [·i.e. 1838 ] Wooden covers. Picture of Buddhist sage Hsu tung on front cover, accompanied by text of his pronouncement on separate leaf on back cover: "A Buddhist priest asked Buddha, 'How did the Buddha attain the most superior way?' Buddha replied, 'Protect the heart from sins; as one shines a mirror by keeping off dust, one can attain enlightenment.'" --i~ ti_ Hsu tung THE ILLUSTRATED BOOK • An Exhibit: March-May 1991 • Compiled by Alice N. Loranth Cleveland Public Library Fine Arts and Special Collections Department PREFACE The Illustrated Book exhibit was assembled to present an overview of the history of book illustration for a general audience. The plan and scope of the exhibit were developed within the confines of available exhibit space on the third floor of Main Library. Materials were selected from the holdings of Special Collections, supplemented by a few titles chosen from the collections of Fine Arts. Selection of materials was further restrained by concern for the physical well-being of very brittle or valuable items. Many rare items were omitted from the exhibit in order to safeguard them from the detrimental effects of an extended exhibit period. Book illustration is a cooperation of word and picture. At the beginning, writing itself was pictorial, as words were expressed through pictorial representation. -

Get This Week's Gazette

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Volume 17, No. 40 A Weekly Newspaper for the Library Staff October 6, 2006 caption tk. Michaela McNichol National Book Festival Presents All Viewpoints to give “60 Minutes” an Readers came early and By AUDREY FISCHER exclusive interview — and stayed late. A half hour not the Bush Administra- before the festival opened he Library’s sixth annual National tion — that prevented Bob at 10 a.m., they began col- Book Festival demonstrated once Woodward from discussing lecting blue CSPAN2 book Tagain that the National Mall in his new book at the National bags and circulating among the nation’s capital is the place where Book Festival (see story on state tables in the Pavilion all voices and points of view can be page 5). News that the New of the States. At 5 p.m., heard. York Times revealed details they were standing three- Last year, the book festival shared about the book in its Sept. 29 to-five deep around the the Mall with antiwar protestors. This issue — two days before its History and Biography year, the festival, which is organized by scheduled release on Oct. 2 — Pavilion, straining to hear the Library of Congress and hosted by sent festival organizers scram- Woodward’s remarks in first lady Laura Bush, presented Pulitzer bling to make sure the book hopes he would talk Prize-winning author and Washington would be on sale at the event. about his book released Post editor Bob Woodward, whose new It joined hundreds of books by earlier that day. book “State of Denial” offers a harsh the 70 participating authors on sale at the Attendance topped last year’s record critique of the Bush Administration’s festival. -

Catalogue 13 2 Catalogue 13

CATALOGUE 13 2 CATALOGUE 13 1904 Coolidge Ave., Altadena, California 91001 · Tel. (626) 297-7700 · [email protected] www.WhitmoreRareBooks.com Books may be reserved by email: [email protected] and by phone: (626) 297-7700 We welcome collectors and dealers to come visit our library by appointment at: 1904 Coolidge Ave., Altadena, CA 91001 For our complete inventory, including many first editions, signed books and other rare items, please visit our website at: www.WhitmoreRareBooks.com Follow us on social media! @WRareBooks @whitmorerarebooks whitmorerarebooks Catalogue 13 1. Ars Moriendi Ars Moriendi ex varijs sententijs collecta... Nurmberge (Nuremberg): J. Weissenburger, [1510]. Octavo (159 × 123 mm). Modern green morocco, spine lettered in gilt, boards single ruled in blind, edges green. Housed in a custom-made green slipcase. 14 woodcuts (the first repeated). Engraved bookplate of Catherine Macdonald to the front pastedown. Minor toning, cut close at foot with loss of portions of the decorative borders, a very good copy. First of three Latin editions printed by Weissenburger. The book derives from the Tractatus (or Speculum) Artis Bene Moriendi, composed in 1415 by an anonymous Dominican friar, probably at the request of the Council of Constance. The Ars Morienda is taken from the second chapter of that work, and deals with the five temptations that beset a dying man (lack of faith, despair, impatience, spiritual pride, and avarice), and how to avoid them. It was first published as a block book around 1450 in the Netherlands, and it was among the first books printed with movable type. It continued to be popular into the 16th century. -

Exhibit Booklet

Books & Culture Quayle Bible Collection Exhibit 2014-2015 Books & Culture was taught in 2014 during the spring se- mester as part of the Quest program. Courses in the Quest core are interdisciplinary in nature and juniors in the program focus on gain- ing “a better understanding of our global society.” The Quayle collection provided these students with an op- portunity not only to explore different cultures within today’s soci- ety, but to consider, as well, how those cultures have changed across time. In the culminating assignment, students selected a book of interest and explored the ways in which it reflected the cul- ture that produced it and influenced subsequent cultural develop- ment. Clay Tablets, Ur, 2000 BCE. These were perhaps the most exotic books selected for the research project. Clay tablets were among the first written records still in existence. Many of them were business records like the tem- ple records displayed here. The black tablet is shown with the re- mains of its envelope. Envelopes were used for contracts and for private or diplomatic correspondence. The writing is “cuneiform,” meaning that the marks on the clay are wedge-shaped. Those marks were made by pressing the edge of a triangular carved reed into the wet clay which were baked to harden them. The tools and techniques of modern archaeology began developing in the late 19th century. Several of these tablets were excavated at that time by Edgar J. Banks, American Consul in Bagh- dad and field director for the Oriental Excavation fund, sponsored by the University of Chicago. -

Download Cityblock an Abrams Block Book Pdf Book by Christopher Franceschelli

Download Cityblock An Abrams Block Book pdf book by Christopher Franceschelli You're readind a review Cityblock An Abrams Block Book book. To get able to download Cityblock An Abrams Block Book you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite ebooks in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this file on an database site. Ebook Details: Original title: Cityblock (An Abrams Block Book) Age Range: 3 - 5 years Grade Level: Preschool - Kindergarten Series: An Abrams Block Book Board book: 96 pages Publisher: Harry N. Abrams; Brdbk edition (September 6, 2016) Language: English ISBN-10: 1419721895 ISBN-13: 978-1419721892 Product Dimensions:5.5 x 2 x 6.6 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 19482 kB Description: Cityblock explores city life in an exciting and unique way, from up in a high-rise building to down in the subway. Divided into three sections—things that go, things to see, and things to eat—it features 24 different aspects of city living. As with the other acclaimed books in the series, die-cut icons hint at the larger context on the next spread.... Review: This series of books is my absolute favorite series for my 2 year old yet that Ive found. The pages are extremely interactive and he loves reading them over and over again. I cant wait until Christmas so that I can purchase them for my nephew as well. I would definitely recommend these as a staple for young children.