Palerang Council Aboriginal History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aborginal and Historic Gap Analysis and Future Direction Report Wilton

ARCHAEOLOGICAL & HERITAGE MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS Greater Macarthur Investigation Area Archaeological Research Design and Management Strategy Final Department of Planning and Environment February 2017 Greater Macarthur Investigation Area Regional Archaeological Research Design and Management Strategy i ARCHAEOLOGICAL & HERITAGE MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS Document Control Page Anita Yousif, Laressa Berehowyj and Fenella AUTHOR/HERITAGE ADVISOR Atkinson CLIENT Department of Planning and Environment Greater Macarthur Investigation Area: PROJECT NAME Archaeological Research Design and Management Strategy REAL PROPERTY DESCRIPTION Various EXTENT PTY LTD INTERNAL REVIEW/SIGN OFF WRITTEN BY DATE VERSION REVIEWED APPROVED Anita Yousif, Laressa Berehowyj and Fenella 31/09/2016 1 Draft Susan McIntyre- Atkinson Tamwoy Susan McIntyre- Anita Yousif, Laressa Tamwoy, Berehowyj and Fenella 10/10/2016 Final Alan Williams Updated Aboriginal Atkinson Draft heritage maps to be substituted once data has been received. Anita Yousif, Laressa Susan McIntyre- Susan McIntyre- Berehowyj and Fenella 3/02/2017 Final Tamwoy Tamwoy Atkinson Copyright and Moral Rights Historical sources and reference materials used in the preparation of this report are acknowledged and referenced in figure captions or in text citations. Reasonable effort has been made to identify, contact, acknowledge and obtain permission to use material from the relevant copyright owners. Unless otherwise specified in the contract terms for this project EXTENT HERITAGE PTY LTD: Vests copyright of all material produced by EXTENT HERITAGE PTY LTD (but excluding pre-existing material and material in which copyright is held by a third party) in the client for this project (and the client’s successors in title); Retains the use of all material produced by EXTENT HERITAGE PTY LTD for this project for EXTENT HERITAGE PTY LTD ongoing business and for professional presentations, academic papers or publications. -

Tallaganda State Forest Compartment 2416 Harvest Plan

LOCALITY MAP Compartments 2416 Tallaganda State Forest No.577 Tallaganda NP SOUTHERN REGION: QUEANBTEaYllANaganda MANA SCAGEM ENT AREA 32> On FCNSW Scale: 1:100,000 unsealed ³ gravel roads G 2416 JEMBAICUMBENE CREEK SHOALHAVEN RIVER BACK CREEK BOURKES CREEK Sealed Road Major Forest Road Major Rivers Minor Forest Road State Forest National Parks Planning Unit Formal Reserve Vacant Crown Land Informal Reserve Non Forest Softwood Plantations Freehold Deua NP Water WITTS CREEK G Emergency Meeting Point Á Evacuation Route and Helicopter Landing Site Á Haulage Route 35 36 37 38 Prepared By: Kate Halton Version: 4 Harvest Plan Operational Map 23> STREAM EXCLUSION ZONES (EPL IHL 1 & TSL) A\PLANNING MANAGER APPROVAL ........................................................................................ Compartment:2416 On FCNSW Operational Zone unsealed Feature Filter Strip Protection Zone APPROVED: Lee Blessington State Forest: TALLAGANDA No: 577 gravel roads ³ Unmapped N/A N/A N/A SOUTHERN REGION - Hardwood Forests Scale: DATE: 27/02/2014 1:15,000 1st Order 5m 5m 10m Map Sheet: BOMBAY 8827-3S Contour Interval 10m 2nd order 5m 15m 10m 3rd order 5m 25m 10m 75 75 2 Rd 4th order 5m 45m 10m Realignment G 0 125 250 500 750 1,000 Tallaganda SCA Meters 0.5-2ha H 3 20m buffer 13 H# 7 H ÉÉ H8 S1 6 ú 2 H ú C1 H C2 ú úS2 H 74 14 H 5 H 74 1 ## H 4 H12 11 H H 10 <0.5ha H 0.5-2ha 10m buffer 20m buffer H 9 <0.5ha 9a 10m buffer LEGEND NON HARVEST AREA ROADS <0.5ha BOUNDARIES Harvesting Protection (FMZ 3A) (100m total) Minor Forest 10m buffer ÉÉÉÉÉÉState Forest Boundary Ridge & Headwater Habitat (80m total width) EPL Standard Existing (Major) Compartment Boundary EPL Standard Existing (Minor) ÉÉÉÉÉÉ Slopes >30 (IHL 4) !A Proposed Control Line EPL Licenced (New Construction) Probable EEC Tablelands Snow Gum, Control Line/SCA FAUNA FEATURES 73 1 Black Sallee, Candlebark and Ribbon B boundary to be marked !A Powerful Owl (Nest/Roost) " Gum Grassy Woodland # ÉÉ with GPS Scarlet Robin 1 Probalbe Wetland & Exc. -

The Builders Labourers' Federation

Making Change Happen Black and White Activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, Union and Liberation Politics Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cook, Kevin, author. Title: Making change happen : black & white activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, union & liberation politics / Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall. ISBN: 9781921666728 (paperback) 9781921666742 (ebook) Subjects: Social change--Australia. Political activists--Australia. Aboriginal Australians--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--20th century. Australia--Social conditions--20th century. Other Authors/Contributors: Goodall, Heather, author. Dewey Number: 303.484 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover images: Kevin Cook, 1981, by Penny Tweedie (attached) Courtesy of Wildlife agency. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History RSSS and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National -

Changes to Driver Licence Sanctions in Your CLSD Region

Changes to Driver Licence Sanctions in Your CLSD Region In 2020, Revenue NSW introduced a hardship program focused on First Nations people and young people. As a result, the use of driver licence sanctions for overdue fine debt changed on Monday 28th September 2020 in some locations. How are overdue fines and driver licence sanctions related? If a person has overdue fines, their driver licence may be suspended. The driver licence suspension may be removed if the person: • pays a lump sum to Revenue NSW, or • enters a payment plan with Revenue NSW, or • is approved for a WDO. A driver licence suspension can be applied for multiple reasons, so even after being told that a driver licence suspension for unpaid fines has been removed, people should always double check that it is OK to drive by contacting Service NSW. Driver licence restrictions can also be put on interstate licences and cannot be removed easily. If you have a client in this situation, they should get legal advice. What has changed? Now, driver licence sanctions will not be imposed as a first response to unpaid fines for enforcement orders that were issued on or after 28 September 2020 to First Nations people and young people who live in the target locations. What are the target locations? Locations that the Australian Bureau of Statistics classifies as: • very remote, • remote • outer regional, and • Inner regional post codes where at least 9% of the population are First Nations People. Included target locations on the South Coast are the towns of Batemans Bay, Bega, Bodalla, Eden, Eurobodalla, Mogo, Narooma, Nowra Hill, Nowra Naval PO, Merimbula, Pambula, Tilba and Wallaga Lake. -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

Edition #10 June 26 2020

Braidwood Bugle FREE Independent News for Braidwood & the District www.braidwoodbugle.com.au Number 10 26 June 2020 Tinkerbell takes to the Tanker Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update With the current spike in COVID-19 numbers throughout parts of Melbourne, and the school holidays approaching, the Local Health District is taking proactive steps to minimise the risk to patients and staff, while keeping any disruption to services to a minimum. All visitors and staff attending the District’s facilities are asked a series of questions during temperature checking and screening. From today, they will also be asked Have you travelled to Melbourne in the last 14 days? If answered ‘yes’, they will be automatically assessed for symptoms and will not be permitted to enter the facility until 14 days from the date they returned from Melbourne. They will also be advised to get tested for COVID-19 should even the mildest of symptoms arise. NSW Health recommends anyone with any mild respiratory symptoms or unexplained fever should be tested for COVID-19. COVID-19 symptoms include: Fever; Runny nose; Cough; Headache; Aches and pains Tiredness (fatigue); Sore throat; Shortness of breath. Southern NSW Local Today is Take Your Dog to Work Day: This is Tinkerbelle, the Health District has established COVID-19 newest recruit for the Charleyong RFS Brigade. Her human is Dave Testing Centres and temporary pop-up clinics Murtagh, Deputy Captain Charleyong RFS Brigade, Nerriga Road, Braidwood. throughout the District, so those with symptoms may be tested and treated quickly INSIDE THIS WEEK - Eden Monaro By-Election Any one heading to an assessment centre Candidate Profiles Pages 16 and 17 MUST call 1800 999 880 before attending. -

Mulloon Creek Baseline Fish Survey Autumn 2016

Mulloon Creek Baseline Fish Survey Autumn 2016 Final report to the Mulloon Institute Institute for Applied Ecology University of Canberra Acknowledgements The authors of this report wish to acknowledge the input, guidance and field assistance provided by Luke Peel. Fish were sampled under NSW Department of Primary Industries Scientific Collection Permit No: P07/0007-5.0. The Mulloon Institute wish to acknowledge the South East Local Land Services in funding of this baseline fish survey, and advice from NSW DPI Fisheries. Cite this report as follows: Starrs, D. and M. Lintermans (2016) Mulloon Creek baseline fish survey. Autumn 2016. Final report to the Mulloon Institute. Institute for Applied Ecology, University of Canberra, Canberra. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ 2 Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Methods.................................................................................................................................................. 6 Results .................................................................................................................................................. 10 Discussion ........................................................................................................................................... -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Exhibition Catalogue Message from Our Co-Chairs

EXHIBITION CATALOGUE MESSAGE FROM OUR CO-CHAIRS In 2019 we are celebrating 10 years of the Schools Reconciliation Challenge (SRC)! For 10 years Reconciliation NSW has been engaging young people and schools in reconciliation. Our theme this year, Speaking and Listening from the Heart has inspired primary and high school students from across NSW and the ACT to create reconciliation-inspired art and writing for the SRC. We continue to be inspired by the contribution these young people, from many different backgrounds, make to reconciliation with their talent and insight. We thank each and every school, teacher, principal, parent and student who has taken part, guided and supported students and each other. It is thanks to their dedication that the SRC continues to grow each year. We are grateful for their hard work and commitment in ensuring that schools are key contributors to reconciliation processes. In 2019 we received 415 art and writing entries from students across NSW and the ACT, each reflecting the theme and their perspectives on Australia’s ongoing reconciliation journey. It is a privilege to see the depth of engagement, insight and commitment to reconciliation in action that students demonstrate ACKNOWLEDGMENT through their art and writing entries. OF COUNTRY The quality of the art and writing entries we received made the selection process for the exhibition Reconciliation NSW hard work. Many of the artworks were developed acknowledges the collaboratively, involving classes or groups of students traditional owners of under the guidance of local Aboriginal artists, parents Country throughout and community members. We thank the panel of NSW and the ACT judges: Jody Broun, Fiona Petersen, Kirli Saunders, and recognises their Jane Waters, Annie Tennant, Yvette Poshoglian and continuing connections Fiona Britton for their time and expertise in selecting to land, waters and this year’s entries. -

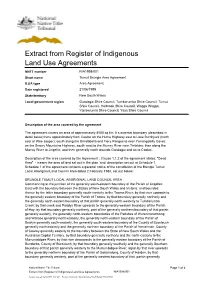

Extract from Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements

Extract from Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements NNTT number NIA1998/001 Short name Tumut Brungle Area Agreement ILUA type Area Agreement Date registered 21/06/1999 State/territory New South Wales Local government region Gundagai Shire Council, Tumbarumba Shire Council, Tumut Shire Council, Holbrook Shire Council, Wagga Wagga, Yarrowlumla Shire Council, Yass Shire Council Description of the area covered by the agreement The agreement covers an area of approximately 8500 sq km. It’s external boundary (described in detail below) runs approximately from Coolac on the Hume Highway east to Lake Burrinjuck (north east of Wee Jasper); south along the Brindabella and Fiery Ranges to near Yarrangobilly Caves on the Snowy Mountains Highway, south west to the Murray River near Tintaldra; then along the Murray River to Jingellic; and then generally north towards Gundagai and on to Coolac. Description of the area covered by the Agreement : Clause 1.1.2 of the agreement states: "Deed Area" - means the area of land set out in the plan `and description set out at Schedule 1. Schedule 1 of the agreement contains a gazettal notice of the constitution of the Brungle Tumut Local Aboriginal Land Council Area dated 2 February 1984, set out below: BRUNGLE TUMUT LOCAL ABORIGINAL LAND COUNCIL AREA Commencing at the junction of the generally south-eastern boundary of the Parish of Jingellec East with the boundary between the States of New South Wales and Victoria: and bounded thence by the latter boundary generally south-easterly to the Tooma River; by that -

Aboriginal Totems

EXPLORING WAYS OF KNOWING, PROTECTING & ACKNOWLEDGING ABORIGINAL TOTEMS ACROSS THE EUROBODALLA SHIRE FAR SOUTH COAST, NSW Prepared by Susan Dale Donaldson Environmental & Cultural Services Prepared for The Eurobodalla Shire Council Aboriginal Advisory Committee FINAL REPORT 2012 THIS PROJECT WAS JOINTLY FUNDED BY COPYRIGHT AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF INDIGNEOUS CULTURAL & INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS Eurobodalla Shire Council, Individual Indigenous Knowledge Holders and Susan Donaldson. The Eurobodalla Shire Council acknowledges the cultural and intellectual property rights of the Indigenous knowledge holders whose stories are featured in this report. Use and reference of this material is allowed for the purposes of strategic planning, research or study provided that full and proper attribution is given to the individual Indigenous knowledge holder/s being referenced. Materials cited from the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Islander Studies [AIATSIS] ‘South Coast Voices’ collections have been used for research purposes. These materials are not to be published without further consent, which can be gained through the AIATSIS. DISCLAIMER Information contained in this report was understood by the authors to be correct at the time of writing. The authors apologise for any omissions or errors. ACKNOWLEDMENTS The Eurobodalla koori totems project was made possible with funding from the NSW Heritage Office. The Eurobodalla Aboriginal Advisory Committee has guided this project with the assistance of Eurobodalla Shire Council staff - Vikki Parsley, Steve Picton, Steve Halicki, Lane Tucker, Shannon Burt and Eurobodalla Shire Councillors Chris Kowal and Graham Scobie. A special thankyou to Mike Crowley for his wonderful images of the Black Duck [including front cover], to Preston Cope and his team for providing advice on land tenure issues and to Paula Pollock for her work describing the black duck from a scientific perspective and advising on relevant legislation. -

Water Research Laboratory

Water Research Laboratory Never Stand Still Faculty of Engineering School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment WRL Technical Report 2017/09 October 2017 by I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Project Details Report Title Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment Report Author(s) I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Report No. 2017/09 Report Status Final Date of Issue 16 October 2017 WRL Project No. 2014105.01 Project Manager Ian Coghlan Client Name 1 Umwelt Australia Pty Ltd Client Address 1 75 York Street PO Box 3024 Teralba NSW 2284 Client Contact 1 Pam Dean-Jones Client Name 2 Eurobodalla Shire Council Client Address 2 89 Vulcan Street PO Box 99 Moruya NSW 2537 Client Contact 2 Norman Lenehan Client Reference ESC Tender IDs 216510 and 557764 Document Status Version Reviewed By Approved By Date Issued Draft J T Carley G P Smith 9 June 2017 Final Draft J T Carley G P Smith 1 September 2017 Final J T Carley G P Smith 16 October 2017 This report was produced by the Water Research Laboratory, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of New South Wales for use by the client in accordance with the terms of the contract. Information published in this report is available for release only with the permission of the Director, Water Research Laboratory and the client. It is the responsibility of the reader to verify the currency of the version number of this report.